User:Volker.haas/Test

Chinese (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語; pinyin: Hànyǔ; literally: "Han language"; or Chinese: 中文; pinyin: Zhōngwén; literally: "Chinese writing") is a group of related. Japanese has no genetic relationship with Chinese,[3] but it makes extensive use of Chinese characters, or kanji (漢字), in its writing system, and a large portion of its vocabulary is borrowed from Chinese. Along with kanji, the Japanese writing system primarily uses two syllabic (or moraic) scripts, hiragana (ひらがな or 平仮名) and katakana (カタカナ or 片仮名). The Korean language (South Korean: 한국어/韓國語 Hangugeo; North Korean: 조선말/朝鮮말 Chosŏnmal) Korean Empire (대한제국; 大韓帝國; Daehan Jeguk) Cyrillic Yeri (Ы) was originally a ligature of Yer and I (Ъ + І = Ы). Iotation was indicated by ligatures formed with the letter І: Ꙗ (not an ancestor of modern Ya, Я, which is derived from Ѧ), Ѥ, Ю (ligature of І and ОУ), Ѩ, Ѭ. Sometimes different letters were used interchangeably, for example И = І = Ї, as were typographical variants like О = Ѻ. There were also commonly used ligatures like ѠТ = Ѿ. Arabic (Arabic: العَرَبِيَّة) al-ʻarabiyyah [alʕaraˈbijːa] (About this soundlisten) or (Arabic: عَرَبِيّ) ʻarabī

Chinese (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語; pinyin: Hànyǔ; literally: "Han language"; or Chinese: 中文; pinyin: Zhōngwén; literally: "Chinese writing") is a group of related.

Japanese has no genetic relationship with Chinese,[3] but it makes extensive use of Chinese characters, or kanji (漢字), in its writing system, and a large portion of its vocabulary is borrowed from Chinese. Along with kanji, the Japanese writing system primarily uses two syllabic (or moraic) scripts, hiragana (ひらがな or 平仮名) and katakana (カタカナ or 片仮名).

The Korean language (South Korean: 한국어/韓國語 Hangugeo; North Korean: 조선말/朝鮮말 Chosŏnmal) Korean Empire (대한제국; 大韓帝國; Daehan Jeguk)

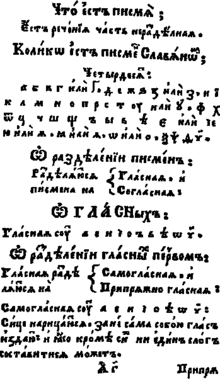

Cyrillic Yeri (Ы) was originally a ligature of Yer and I (Ъ + І = Ы). Iotation was indicated by ligatures formed with the letter І: Ꙗ (not an ancestor of modern Ya, Я, which is derived from Ѧ), Ѥ, Ю (ligature of І and ОУ), Ѩ, Ѭ. Sometimes different letters were used interchangeably, for example И = І = Ї, as were typographical variants like О = Ѻ. There were also commonly used ligatures like ѠТ = Ѿ.

Arabic (Arabic: العَرَبِيَّة) al-ʻarabiyyah [alʕaraˈbijːa] (About this soundlisten) or (Arabic: عَرَبِيّ) ʻarabī

Chinese Examples[edit]

| English | Traditional characters | Simplified characters | Pinyin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello! | 你好! | Nǐ hǎo! | |

| What is your name? | 你叫什麼名字? | 你叫什么名字? | Nǐ jiào shénme míngzi? |

| My name is... | 我叫... | Wǒ jiào ... | |

| How are you? | 你好嗎?/ 你怎麼樣? | 你好吗?/ 你怎么样? | Nǐ hǎo ma? / Nǐ zěnmeyàng? |

| I am fine, how about you? | 我很好,你呢? | Wǒ hěn hǎo, nǐ ne? | |

| I don't want it / I don't want to | 我不要。 | Wǒ bú yào. | |

| Thank you! | 謝謝! | 谢谢! | Xièxie |

| Welcome! / You're welcome! (Literally: No need to thank me!) / Don't mention it! (Literally: Don't be so polite!) | 歡迎!/ 不用謝!/ 不客氣! | 欢迎!/ 不用谢!/ 不客气! | Huānyíng! / Búyòng xiè! / Bú kèqì! |

| Yes. / Correct. | 是。 / 對。/ 嗯。 | 是。 / 对。/ 嗯。 | Shì. / Duì. / M. |

| No. / Incorrect. | 不是。/ 不對。/ 不。 | 不是。/ 不对。/ 不。 | Búshì. / Bú duì. / Bù. |

| When? | 什麼時候? | 什么时候? | Shénme shíhou? |

| How much money? | 多少錢? | 多少钱? | Duōshǎo qián? |

| Can you speak a little slower? | 您能說得再慢些嗎? | 您能说得再慢些吗? | Nín néng shuō de zài mànxiē ma? |

| Good morning! / Good morning! | 早上好! / 早安! | Zǎoshang hǎo! / Zǎo'ān! | |

| Goodbye! | 再見! | 再见! | Zàijiàn! |

| How do you get to the airport? | 去機場怎麼走? | 去机场怎么走? | Qù jīchǎng zěnme zǒu? |

| I want to fly to London on the eighteenth | 我想18號坐飛機到倫敦。 | 我想18号坐飞机到伦敦。 | Wǒ xiǎng shíbā hào zuò fēijī dào Lúndūn. |

| How much will it cost to get to Munich? | 到慕尼黑要多少錢? | 到慕尼黑要多少钱? | Dào Mùníhēi yào duōshǎo qián? |

| I don't speak Chinese very well. | 我的漢語說得不太好。 | 我的汉语说得不太好。 | Wǒ de Hànyǔ shuō de bú tài hǎo. |

| Do you speak English? | 你會說英語嗎? | 你会说英语吗? | Nǐ huì shuō Yīngyǔ ma? |

| I have no money. | 我沒有錢。 | 我没有钱。 | Wǒ méiyǒu qián. |

Japanese Examples =[edit]

Japanese nouns have no grammatical number, gender or article aspect. The noun hon (本) may refer to a single book or several books; hito (人) can mean "person" or "people", and ki (木) can be "tree" or "trees". Where number is important, it can be indicated by providing a quantity (often with a counter word) or (rarely) by adding a suffix, or sometimes by duplication (e.g. 人人, hitobito, usually written with an iteration mark as 人々). Words for people are usually understood as singular. Thus Tanaka-san usually means Mr./Ms. Tanaka. Words that refer to people and animals can be made to indicate a group of individuals through the addition of a collective suffix (a noun suffix that indicates a group), such as -tachi, but this is not a true plural: the meaning is closer to the English phrase "and company". A group described as Tanaka-san-tachi may include people not named Tanaka. Some Japanese nouns are effectively plural, such as hitobito "people" and wareware "we/us", while the word tomodachi "friend" is considered singular, although plural in form.

Verbs are conjugated to show tenses, of which there are two: past and present (or non-past) which is used for the present and the future. For verbs that represent an ongoing process, the -te iru form indicates a continuous (or progressive) aspect, similar to the suffix ing in English. For others that represent a change of state, the -te iru form indicates a perfect aspect. For example, kite iru means "He has come (and is still here)", but tabete iru means "He is eating".

Questions (both with an interrogative pronoun and yes/no questions) have the same structure as affirmative sentences, but with intonation rising at the end. In the formal register, the question particle -ka is added. For example, ii desu (いいです) "It is OK" becomes ii desu-ka (いいですか。) "Is it OK?". In a more informal tone sometimes the particle -no (の) is added instead to show a personal interest of the speaker: Dōshite konai-no? "Why aren't (you) coming?". Some simple queries are formed simply by mentioning the topic with an interrogative intonation to call for the hearer's attention: Kore wa? "(What about) this?"; O-namae wa? (お名前は?) "(What's your) name?".

Negatives are formed by inflecting the verb. For example, Pan o taberu (パンを食べる。) "I will eat bread" or "I eat bread" becomes Pan o tabenai (パンを食べない。) "I will not eat bread" or "I do not eat bread". Plain negative forms are actually i-adjectives (see below) and inflect as such, e.g. Pan o tabenakatta (パンを食べなかった。) "I did not eat bread".

The so-called -te verb form is used for a variety of purposes: either progressive or perfect aspect (see above); combining verbs in a temporal sequence (Asagohan o tabete sugu dekakeru "I'll eat breakfast and leave at once"), simple commands, conditional statements and permissions (Dekakete-mo ii? "May I go out?"), etc.

The word da (plain), desu (polite) is the copula verb. It corresponds approximately to the English be, but often takes on other roles, including a marker for tense, when the verb is conjugated into its past form datta (plain), deshita (polite). This comes into use because only i-adjectives and verbs can carry tense in Japanese. Two additional common verbs are used to indicate existence ("there is") or, in some contexts, property: aru (negative nai) and iru (negative inai), for inanimate and animate things, respectively. For example, Neko ga iru "There's a cat", Ii kangae-ga nai "[I] haven't got a good idea".

The verb "to do" (suru, polite form shimasu) is often used to make verbs from nouns (ryōri suru "to cook", benkyō suru "to study", etc.) and has been productive in creating modern slang words. Japanese also has a huge number of compound verbs to express concepts that are described in English using a verb and an adverbial particle (e.g. tobidasu "to fly out, to flee," from tobu "to fly, to jump" + dasu "to put out, to emit").

There are three types of adjectives (see Japanese adjectives):

- 形容詞 keiyōshi, or i adjectives, which have a conjugating ending i (い) (such as 暑い atsui "to be hot") which can become past (暑かった atsukatta "it was hot"), or negative (暑くない atsuku nai "it is not hot"). Note that nai is also an i adjective, which can become past (暑くなかった atsuku nakatta "it was not hot").

- 暑い日 atsui hi "a hot day".

- 形容動詞 keiyōdōshi, or na adjectives, which are followed by a form of the copula, usually na. For example, hen (strange)

- 変なひと hen na hito "a strange person".

- 連体詞 rentaishi, also called true adjectives, such as ano "that"

- あの山 ano yama "that mountain".

Both keiyōshi and keiyōdōshi may predicate sentences. For example,

- ご飯が熱い。 Gohan ga atsui. "The rice is hot."

- 彼は変だ。 Kare wa hen da. "He's strange."

Both inflect, though they do not show the full range of conjugation found in true verbs. The rentaishi in Modern Japanese are few in number, and unlike the other words, are limited to directly modifying nouns. They never predicate sentences. Examples include ookina "big", kono "this", iwayuru "so-called" and taishita "amazing".

Both keiyōdōshi and keiyōshi form adverbs, by following with ni in the case of keiyōdōshi:

- 変になる hen ni naru "become strange",

and by changing i to ku in the case of keiyōshi:

- 熱くなる atsuku naru "become hot".

The grammatical function of nouns is indicated by postpositions, also called particles. These include for example:

- が ga for the nominative case.

- 彼がやった。Kare ga yatta. "He did it."

- に ni for the dative case.

- 田中さんにあげて下さい。 Tanaka-san ni agete kudasai "Please give it to Mr. Tanaka."

It is also used for the lative case, indicating a motion to a location.

- 日本に行きたい。 Nihon ni ikitai "I want to go to Japan."

- However, へ e is more commonly used for the lative case.

- パーティーへ行かないか。 pātī e ikanai ka? "Won't you go to the party?"

- の no for the genitive case, or nominalizing phrases.

- 私のカメラ。 watashi no kamera "my camera"

- スキーに行くのが好きです。 Sukī-ni iku no ga suki desu "(I) like going skiing."

- を o for the accusative case.

- 何を食べますか。 Nani o tabemasu ka? "What will (you) eat?"

- は wa for the topic. It can co-exist with the case markers listed above, and it overrides ga and (in most cases) o.

- 私は寿司がいいです。 Watashi wa sushi ga ii desu. (literally) "As for me, sushi is good." The nominative marker ga after watashi is hidden under wa.

Note: The subtle difference between wa and ga in Japanese cannot be derived from the English language as such, because the distinction between sentence topic and subject is not made there. While wa indicates the topic, which the rest of the sentence describes or acts upon, it carries the implication that the subject indicated by wa is not unique, or may be part of a larger group.

- Ikeda-san wa yonjū-ni sai da. "As for Mr. Ikeda, he is forty-two years old." Others in the group may also be of that age.

Absence of wa often means the subject is the focus of the sentence.

- Ikeda-san ga yonjū-ni sai da. "It is Mr. Ikeda who is forty-two years old." This is a reply to an implicit or explicit question, such as "who in this group is forty-two years old?"

Korean examples[edit]

Below is a chart of the Korean alphabet's symbols and their canonical IPA values:

| Hangul 한글 | ㅂ | ㄷ | ㅈ | ㄱ | ㅃ | ㄸ | ㅉ | ㄲ | ㅍ | ㅌ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅅ | ㅎ | ㅆ | ㅁ | ㄴ | ㅇ | ㄹ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | b | d | j | g | pp | tt | jj | kk | p | t | ch | k | s | h | ss | m | n | ng | r, l |

| IPA | p | t | t͡ɕ | k | p͈ | t͈ | t͡ɕ͈ | k͈ | pʰ | tʰ | t͡ɕʰ | kʰ | s | h | s͈ | m | n | ŋ | ɾ, l |

| Hangul 한글 | ㅣ | ㅔ | ㅚ | ㅐ | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅜ | ㅓ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅖ | ㅒ | ㅑ | ㅛ | ㅠ | ㅕ | ㅟ | ㅞ | ㅙ | ㅘ | ㅝ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | i | e | oe | ae | a | o | u | eo | eu | ui | ye | yae | ya | yo | yu | yeo | wi | we | wae | wa | wo |

| IPA | i | e | ø, we | ɛ | a | o | u | ʌ | ɯ | ɰi | je | jɛ | ja | jo | ju | jʌ | ɥi, wi | we | wɛ | wa | wʌ |

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (RR/MR) | North (Hangul) | South (RR/MR) | South (Hangul) | ||

| 읽고 | to read (continuative form) |

ilko (ilko) | 일코 | ilkko (ilkko) | 일꼬 |

| 압록강 | Amnok River | amrokgang (amrokkang) | 암록깡 | amnokkang (amnokkang) | 암녹깡 |

| 독립 | independence | dongrip (tongrip) | 동립 | dongnip (tongnip) | 동닙 |

| 관념 | idea / sense / conception | gwallyeom (kwallyŏm) | 괄렴 | gwannyeom (kwannyŏm) | 관념 |

| 혁신적* | innovative | hyeoksinjjeok (hyŏksintchŏk) | 혁씬쩍 | hyeoksinjeok (hyŏksinjŏk) | 혁씬적 |

Cyrillic Examples[edit]

Cyrillic script spread throughout the East Slavic and some South Slavic territories, being adopted for writing local languages, such as Old East Slavic. Its adaptation to local languages produced a number of Cyrillic alphabets, discussed hereafter.

| А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | Ѕ[3] | Ꙁ | И | І | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | ОУ[4] | Ф |

| Х | Ѡ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | ЪІ[5] | Ь | Ѣ | Ꙗ | Ѥ | Ю | Ѫ | Ѭ | Ѧ | Ѩ | Ѯ | Ѱ | Ѳ | Ѵ | Ҁ[6] |

Capital and lowercase letters were not distinguished in old manuscripts.

Yeri (Ы) was originally a ligature of Yer and I (Ъ + І = Ы). Iotation was indicated by ligatures formed with the letter І: Ꙗ (not an ancestor of modern Ya, Я, which is derived from Ѧ), Ѥ, Ю (ligature of І and ОУ), Ѩ, Ѭ. Sometimes different letters were used interchangeably, for example И = І = Ї, as were typographical variants like О = Ѻ. There were also commonly used ligatures like ѠТ = Ѿ.

The letters also had numeric values, based not on Cyrillic alphabetical order, but inherited from the letters' Greek ancestors.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| А | В | Г | Д | Є | Ѕ | З | И | Ѳ |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| І | К | Л | М | Н | Ѯ | Ѻ | П | Ч (Ҁ) |

| 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 |

| Р | С | Т | Ѵ | Ф | Х | Ѱ | Ѿ | Ц |

The early Cyrillic alphabet is difficult to represent on computers. Many of the letterforms differed from those of modern Cyrillic, varied a great deal in manuscripts, and changed over time. Few fonts include glyphs sufficient to reproduce the alphabet. In accordance with Unicode policy, the standard does not include letterform variations or ligatures found in manuscript sources unless they can be shown to conform to the Unicode definition of a character.

The Unicode 5.1 standard, released on 4 April 2008, greatly improves computer support for the early Cyrillic and the modern Church Slavonic language. In Microsoft Windows, the Segoe UI user interface font is notable for having complete support for the archaic Cyrillic letters since Windows 8.[citation needed]

| Letters of the Cyrillic alphabet (see also Cyrillic digraphs) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А A |

Б Be |

В Ve |

Г Ge |

Ґ Ghe upturn |

Д De |

Ђ Dje |

Ѓ Gje |

Е Ye |

Ё Yo |

Є Ukrainian Ye |

Ж Zhe |

| З Ze |

З́ Zje |

Ѕ Dze |

И I |

І Dotted I |

Ї Yi |

Й Short I |

Ј Je |

К Ka |

Л El |

Љ Lje |

М Em |

| Н En |

Њ Nje |

О O |

П Pe |

Р Er |

С Es |

С́ Sje |

Т Te |

Ћ Tshe |

Ќ Kje |

У U |

Ў Short U |

| Ф Ef |

Х Kha |

Ц Tse |

Ч Che |

Џ Dzhe |

Ш Sha |

Щ Shcha |

Ъ Hard sign (Yer) |

Ы Yery |

Ь Soft sign (Yeri) |

Э E |

Ю Yu |

| Я Ya |

|||||||||||

| Important Cyrillic non-Slavic letters | |||||||||||

| Ӏ Palochka |

Ә Cyrillic Schwa |

Ғ Ayn |

Ҙ Bashkir Dhe |

Ҫ Bashkir The |

Ҡ Bashkir Qa |

Җ Zhje |

Қ Ka with descender |

Ң Ng |

Ҥ En-ghe |

Ө Barred O |

Ү Straight U |

| Ұ Straight U with stroke |

Һ Shha (He) |

Ҳ Kha with descender |

Ӑ A with breve | ||||||||

| Cyrillic letters used in the past | |||||||||||

| Ꙗ A iotified |

Ѥ E iotified |

Ѧ Yus small |

Ѫ Yus big |

Ѩ Yus small iotified |

Ѭ Yus big iotified |

Ѯ Ksi |

Ѱ Psi |

Ꙟ Yn |

Ѳ Fita |

Ѵ Izhitsa |

Ѷ Izhitsa okovy |

| Ҁ Koppa |

ОУ Uk |

Ѡ Omega |

Ѿ Ot |

Ѣ Yat |

|||||||