User:Vkouakou/sandbox

Article Evaluation[edit]

I think that everything in the articles I read was relevant to the topic. There nothing in the articles that particularly distracted me from the main idea. I would consider these articles to be neutral as I did not feel persuaded to think a certain way about any specific viewpoint. Furthermore, I do not believe that any viewpoints were overrepresented. All the reference links I checked work and did support the claims made in the articles. Each source I checked was either a peer-reviewed article in a journal or a government website. These are sources that generally have to be neutral to be published so I would assume that they are not biased. The oldest source I could find on any of the articles was from the mid-1960s but the information from the source was relevant to the history of the Census. The articles seem to be pretty well maintained and have up-to-date, current information with the necessary citations. Most of the conversations on the talk page seem to be about fact-checking and rewording/removing certain parts. People are asking questions about the information to make sure that it has an original source, citation, and is not biased.The U.S Census Bureau article is rated as "C-Class" in all categories. It is apart of 4 WikiProjects- Government, Public Policy, Economics and, Elections and Referendums.Unsurprisingly, the wikipedia articles go more in depth about the topic but overall, I think we received a good summary in class. In class, we covered most of the things the article mentioned. Nice work with your evaluation - Prof Hammad

Selected Article-Gerrymandering[edit]

The gerrymandering article needs more citations and verified sources because a lot of the information in the most important sections is lacking these two things. I thinkthe biggest contribution I can make to this article would be to find reliable sources that backup the information already there. If I find sources that go against what the article already says, I will ask my fellow editors their opinion on what to do and then we will figure out what to do from there.

Possible sources include:

Chen, Jowei, and David Cottrell. “Evaluating Partisan Gains from Congressional Gerrymandering: Using Computer Simulations to Estimate the Effect of Gerrymandering in the U.S. House.” Electoral Studies, vol. 44, 2016, pp. 329–340., doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.06.014.

Cooper, Michael. “5 Ways to Tilt an Election.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 7 Oct. 2010, http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/weekinreview/20100925-redistricting-graphic.pdf

Forgette, Richard, and John W. Winkle. “Partisan Gerrymandering and the Voting Rights Act.” Social Science Quarterly, vol. 87, no. 1, 2006, pp. 155–173. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42956115.

Kennedy, Sheila Suess. “Electoral Integrity: How Gerrymandering Matters.” Public Integrity, vol. 19, no. 3, 2016, pp. 265–273., doi:10.1080/10999922.2016.1225480

I am having some difficultly finding relevant and appropriate sources but as I find more, they will be added o the bibliography

Article Editing-Gerrymandering: Sections Gerrymandering Tactics & Examples of Gerrymandered Districts[edit]

The primary goals of gerrymandering are to maximize the effect of supporters' votes and to minimize the effect of opponents' votes. A partisan gerry mander's main purpose is to influence not only the districting statute but the entire corpus of legislative decisions enacted in its path. [1]

These can be accomplished through a number of ways:[2]

- "Cracking" involves spreading voters of a particular type among many districts in order to deny them a sufficiently large voting bloc in any particular district.[2] Political parties in charge of redrawing district lines may create more "cracked" districts as a means of retaining, and possibly even expanding, their legislative power. By "cracking" districts, a political party would be able to maintain, or gain, legislative control by ensuring that the opposing party's voters are not the majority in specific districts.[3] An example would be to split the voters in an urban area among several districts wherein the majority of voters are suburban, on the presumption that the two groups would vote differently, and the suburban voters would be far more likely to get their way in the elections.

- "Packing" is to concentrate as many voters of one type into a single electoral district to reduce their influence in other districts.[2] In some cases, this may be done to obtain representation for a community of common interest (such as to create a majority-minority district), rather than to dilute that interest over several districts to a point of ineffectiveness (and, when minority groups are involved, to avoid likely lawsuits charging racial discrimination). When the party controlling the districting process has a statewide majority, packing is usually not necessary to attain partisan advantage; the minority party can generally be "cracked" everywhere. Packing is therefore more likely to be used for partisan advantage when the party controlling the districting process has a statewide minority, because by forfeiting a few districts packed with the opposition, cracking can be used in forming the remaining districts.

- "Hijacking" redraws two districts in such a way as to force two incumbents to run against each other in one district, ensuring that one of them will be eliminated.[2]

- "Kidnapping" moves an incumbent's home address into another district.[2] Reelection can become more difficult when the incumbent no longer resides in the district, or possibly faces reelection from a new district with a new voter base. This is often employed against politicians who represent multiple urban areas, in which larger cities will be removed from the district in order to make the district more rural.

These tactics are typically combined in some form, creating a few "forfeit" seats for packed voters of one type in order to secure more seats and greater representation for voters of another type. are often This results in candidates of one party (the one responsible for the gerrymandering) winning by small majorities in most of the districts, and another party winning by a large majority in only a few of the districts.

|

North Carolina's 12th congressional district between 2003 and 2016 is an example of packing. The district has predominantly African-American residents who vote for Democrats. |

| Designed to proportionally segment voters of the Democratic Party, California's 23rd congressional district, was confined to a narrow strip of coast, an example of the packing style of districting. The district was redrawn after the 2010 census by California's non-partisan commission and no longer follows these boundaries. | |

|

California's 11th congressional district drawn to favor its then-Republican incumbent. It was redrawn after the 2010 census. |

|

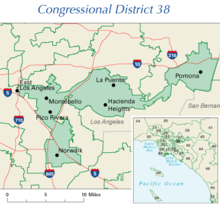

Bi-partisan incumbent gerrymandering produced California District 38, home to Grace Napolitano, a Democrat, who ran unopposed in 2004. This district was redrawn by California's non-partisan commission after the 2010 census. |

|

Texas' controversial 2003 partisan gerrymander produced Texas District 22 for former Rep. Tom DeLay, a Republican. |

|

The odd shapes of California Senate districts in southern California (2008) have led to complaints of gerrymandering. |

|

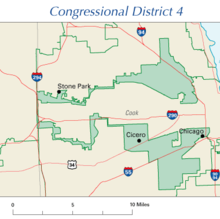

The earmuff shape of Illinois's 4th congressional district packs two Hispanic areas while retaining narrow contiguity along Interstate 294. |

|

After the Democrat Jim Matheson was elected in 2000, the Utah legislature redrew the 2nd congressional district to favor future Republican majorities. The predominantly Democratic city of Salt Lake City was connected to predominantly Republican eastern and southern Utah through a thin sliver of land running through Utah County. Nevertheless, Matheson continued to be re-elected. In 2011, the legislature created new congressional districts that combined conservative rural areas with more urban areas to dilute Democratic votes. |

|

Illinois's 17th congressional district in the western portion of the state was gerrymandered: the major urban centers are anchored and Decatur is included, although nearly isolated from the main district. It was redrawn in 2013. |

|

Maryland's 3rd congressional district was listed in the top ten of the most gerrymandered districts in the United States by The Washington Post in 2014. [4] The district is drawn to favor Democrat candidates. |

|

North Carolina's 4th congressional district encompasses parts of Raleigh, Hillsborough, and the entirety of Chapel Hill. The district is considered to be one of the most gerrymandered districts in North Carolina and the United States as a whole.[4] The district was redrawn in 2017. |

This table is from the original article and lacks sources. I found sources that support some of the information in the table and some that can be added to it. The citations and photos for the table will be added. I am still looking for reliable sources that can be used to verify the information in the article. They will be added as they are found.

- Professor Hammad, it seems that someone else has been doing some MAJOR editing to the gerrymandering page. There has been quite a few additions to the page in the last couple days and it is almost impossible to can edit the new sections adequately. I thought I would let you know just in case you were wondering what my contributions were. -Vanessa

This is a user sandbox of Vkouakou. You can use it for testing or practicing edits.

This is a user sandbox of Vkouakou. You can use it for testing or practicing edits.

This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course.

To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section.

- ^ Schuck, Peter H. (1987). "The Thickest Thicket: Partisan Gerrymandering and Judicial Regulation of Politics". Columbia Law Review. 87 (7): 1325–1384. doi:10.2307/1122527.

- ^ a b c d e Pierce, Olga; Larson, Jeff; Beckett, Lois (November 2, 2011). "Redistricting, a Devil's Dictionary". ProPublica. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- ^ "Packing and cracking: The Supreme Court takes up partisan gerrymandering". Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ^ a b Ingraham, Christopher (2014-05-15). "America's most gerrymandered congressional districts". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2018-03-29.