User:Mdd/History of agricultural science

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

The History of agricultural science deals with different thinkers and theories in the subject of agricultural science from the ancient world to the present day. Since Ancient times authors wrote about agriculture, but in daily life knowledge and experience of agriculture remained verbally transmitted from farmer to farmer.[1]

Agriculture began to be studied, as a science by individuals, in the principal countries of Europe, about the middle of the 16th century.[2] In the 18th century in Central Europe the first practical agricultural schools were founded to educate farmers, and the first professorships of agriculture emerged at some European universities.[3]

In the 19th century programs to considered agriculture as a science inaugurated the scientific approach in agriculture. More specialized books, magazines, newspapers started to occur. Nationally and provincially agricultural societies where initiated, and in the second part of the 19th century the first departments of agriculture at universities occurred.

Overview[edit]

The term "History of agricultural science" can relate historical development of the agricultural science, and to the academic study of this historical development.

The ideas about the origin of agricultural science have been evolving in time. Early 19th century John Claudius Loudon pinpointed the origin in the middle of the 16th century, reference to the work of Walter Harte (1764). Loudon (1825, p. 47) stated:

- Agriculture began to be studied, as a science, in the principal countries of Europe, about the middle of the 16th century. The works of Crescenzio in Italy, Olivier de Serres in France, Heresbach in Germany, Herrera in Spain, and Fitzherbert in England, all published about that period, supplied the materials of study, and led to improved practices among the reading agriculturists.

The British agriculturalist E. John Russell (1872-1965) in his "A history of agricultural science in Great Britain, 1620-1954," published postmortem in 1966 confirms Loudons thesis. A review of this work reveals:

- Sir John Russell traces the development of agricultural science in Great Britain over three and a half centuries. It makes an interesting story, beginning with Sir Francis Bacon, the first scientist to display any interest in agriculture, who published his Novum Organum in 1620, and continuing into this century with accounts of many individuals who worked in universities or privately at their own expense or with private endowments.[4]

Loudon focussed on the first scientifically based writings, while nowadays the Encyclopedia Britannica (2014), focusses on the period in time, that agriculture found its place in the academic structure, stating:

- Although much was written about agriculture during the Middle Ages, the agricultural sciences did not then gain a place in the academic structure. Eventually, a movement began in central Europe to educate farmers in special academies, the earliest of which was established at Keszthely, Hungary, in 1796. Students were still taught only the experiences of farmers, however... The scientific approach was inaugurated in 1840 by Justus von Liebig of Darmstadt, Germany.[1]

Historical development of agricultural science[edit]

Ancient knowledge of agriculture[edit]

Ephraim Chambers (1741, Vol 1. p. 48) in the Cyclopaedia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences gave an early accounts on the authors on agriculture (online).

- AGRICULTURE: ... We forbear to say anything about the antiquity or usefulness of this art ; every reader's imagination will supply that defect. - It has been cultivated by many of the greatest Men among the Ancients: as Emperors, Dictators, and Consuls ; and has been treated of by some of their greatest authors : Virgil for instance, Cato, Varro, Columella,

- The later authors on Agriculture, are Palladius Constantius, Caesar, Baptista Porta, Heresbachius, and Agricola in Latin; Alphonso Herrera, in Italian ; Stephens, Liebaut, de Serree, de Croiscens, Bellon, and Chomel, in French; and Evelyn, Mortimer, Switzer, Bradley, and Lawrence, in English. See GEOPONIC

This was not the earliest account. The term Geoponic was already known, and described by Chambers as:

- GEOPONIC, sometimes relating to Agriculture. Thus Cato, Varro, Columella, Palladius, and Pliny, are sometimes called Geoponic writers. See GEORGIC[5]

The Encyclopedia Britannica (2014) about the origin of agricultural knowledge:

- Early knowledge of agriculture was a collection of experiences verbally transmitted from farmer to farmer. Some of this ancient lore had been preserved in religious commandments, but the traditional sciences rarely dealt with a subject seemingly considered so commonplace.[1]

These Ancient writers on husbandry and agriculture from Greece and Rome are called Geoponici. In general the Greeks paid less attention than the Romans to the scientific study of these subjects, which in classical times they regarded as a branch of economics.

What we know of the agriculture of Greece is chiefly derived from the poem of Hesiod, entitled Works and Days. Some incidental remarks on the subject may be found in the writings of Herodotus, Xenophon, Theophrastus, and others. Varro, a Roman, writing in the century preceding the commencement of our era, informs us, that there were more than fifty authors, who might at that time be consulted on the subject of agriculture, all of whom were ancient Greeks, except Mago the Carthaginian. Among them he includes Democritus, Xenophon, Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Hesiod. The works of the other writers he enumerates have been lost; and indeed all that remain of Democritus are only a few extracts preserved in the Geoponika, an agricultural treatise published at Constantinople by the Greeks of the fourth or fifth centuries of our aora. Xenophon, Aristotle, Homer, and others, touch on our subject but very slightly.[6]

The Roman authors on agriculture, whose works have reached the present age, are Cato the Elder, Marcus Terentius Varro, Virgil, Columella, Pliny the Elder, and Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius; there were many more, whose writings are lost.[7] The Romans, aware of the necessity of maintaining a numerous and thriving order of agriculturists, from very early times endeavoured to instill into their countrymen both a theoretical and a practical knowledge of the subject. The occupation of the farmer was considered next in importance to that of the soldier, and distinguished Romans did not disdain to practice it.

The Encyclopedia Britannica (2014):

- Although much was written about agriculture during the Middle Ages, the agricultural sciences did not then gain a place in the academic structure.[1]

Early modern period[edit]

Loudon (1825, p. 47) with a reference to the work of Walter Harte (1764)

- Agriculture began to be studied, as a science, in the principal countries of Europe, about the middle of the 16th century. The works of Crescenzio in Italy, Olivier de Serres in France, Heresbach in Germany, Herrera in Spain, and Fitzherbert in England, all published about that period, supplied the materials of study, and led to improved practices among the reading agriculturists. The art received a second impulse in the middle of the century following, after the general Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle. Then, as Harte has observed (Essays, i. p. 32.),

- "almost all the European nations, by a sort of tacit consent, applied themselves to the study of agriculture, and continued to do so, more or less, even amidst the universal confusion that soon succeeded."[8]

Loudon (1825, p. 41):

- The study of agriculture in England in the early part of the sixteenth century, and probably for a long time before, is thus ascertained; for Anthony Fitzherbert no where speaks of the practices which he describes or recommends as of recent introduction. The Book of Surveying adds considerably to our knowledge of the rural economy of that age.[9]

Loudon (1825, p. 47)

- During the 18th century, the march of agriculture has been progressive throughout Europe, with little exception; and it has attained to a very considerable degree of perfection, in some districts of Italy, in the Netherlands, and in Great Britain, in Spain it has been least improved, and it is still in a very backward state in most parts of Hungary, Poland, and Russia. We shall, in the following sections, give such notices of the agriculture of these and the other countries of Europe, as we have been enabled to glean from the very scanty materials which exist on the subject. Had these been more abundant, this part of our work would have been much more instructive. The past state of agriculture can do little more than gratify the curiosity, but its present state is calculated both to excite our curiosity and affect our interests. Independently of the political relations which may be established by a free trade in corn, there is probably no European country that does not possess some animal or vegetable production, or pursue some mode of culture or management, that might not be beneficially introduced into Britain; but, with the exception of Flanders and some parts of France and Italy, there are as yet no sufficient data for obtaining the necessary details.[2]

Alfred Charles True (1929, p. 6):

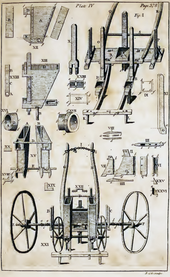

- During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a considerable literature on agricultural subjects was developed in a number of European countries. The writings of certain ancient authors on such subjects were also available during this period, particularly those of Virgil, Columella, and Varro. In France the publication of works on agriculture was much stimulated by the great series of volumes commonly called the Encyclopédie (1751-1780), which contained articles on this subject. In Great Britain there were agricultural works by about 200 authors before 1800. Among English publications which had an important influence in the United States was Jethro Tull's Horse Hoeing Husbandry, or a Treatise on the Principles of Tillage and Vegetation, three editions of which were published between 1733 and 1751. The Annals of Agriculture and Other Useful Arts, a periodical begun in London in 1784 by Arthur Young (1741-1820), widely promoted the advancement of agriculture in Europe and America. [10]

Agricultural reformers[edit]

Harro Maat (2001):

- ... modernisation of European agriculture in the late eighteenth century is generally attributed to various members of the rural elite, like Jethro Tull (1674-1740) and Arthur Young (1741-1820) in England, Albrecht D. Thaer (1752-1828) in Germany and Henri L. Duhamel du Monceau (1700-1782) in France. it can be questioned whether the source of innovation was really their own activity. Agricultural historians have pointed out that innovation in agriculture was much more a long-term development than a revolutionary change, stemming from farm experience moving through Europe by all sorts of travelling 'agents'. Moreover, it is questionable whether the influence of these men on agriculture is based on their erudition in the subject or because of their social and political position.[11]

Beside the elite also some prominent pastors played their part, such as pastor Johann Friedrich Mayer (1719–1798) in Germany and pastor hu:Tessedik Sámuel (1742-1820) in Hungary.

Practical agricultural schools[edit]

The Encyclopedia Britannica (2014):

- Eventually, a movement began in central Europe to educate farmers in special academies, the earliest of which was established at Keszthely, Hungary, in 1796.[1]

Jean Bérenger (1997) explains more in detail about hu:Tessedik Sámuel (1742-1820), Imre Festetics (1764–1847) and the developments in Hungary late 18th century:

- Pastor Tessedik was a pioneer in his parish of Szarvas in Transdanubia which he transformed by planting acacias and vegetable gardens so that a deserted region became a real oasis. He introduced fodder crops and so offered a serious alternative to the classic cycle of leaving a field fallow every third year. In 1780 he started the first practical agricultural school open to commoners. The teachers came from Vienna, Poszony, Sopron and Buda and gave the students lessons in agronomy and the sciences, including the natural sciences, hygiene and meteorology, a syllabus which represented a complete departure from traditional classical studies. In 1790 the school had about a thousand students, despite the hostility of the county authorities who were disturbed by the sight of young peasants making such rapid progress. Tessedik did receive support from the Habsburgs. Joseph II decorated him in 1787 and Leopold II accorded him many audiences. The school, however, later fell victim to reaction. It was closed by an administrative decision in 1796 but was reopened in 1799 exclusively for the sons of intendants on the estates. Two years later, count Festetich, an enlightened aristocrat, opened at Keszthely an agricultural college to educate intendants who had been admitted to the lesser nobility. Tessedik published his writings on agronomy in Germany and Hungary, his most important work probably being The Peasant in Hungary; what he is and what he ought to be. He recommended that the system of three-year rotation should be abandoned and that new crops be introduced together with intensive farming. Root vegetables and forage plants made it possible to raise stock away from the field and animal manure increased the yield from cereal crops.[12]

In German early 19th century Theodor Konrad von Kretschmann, minister of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, had asked Franz Körte to take on the organisation of an agricultural/economical teaching institute in Marloffstein in association with the local economy professor Michael Alexander Lips (1779-1838) at the University of Erlangen.

Agriculture science, early 19th century[edit]

Professorships of agriculture[edit]

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Vol 1 (1998). p. 156 further explains:

- There was, however, no formal agricultural education or research until 1796, when a special academy was founded at Keszthely, Hung; and professorships of agriculture and rural economy were founded at the universities of Edinburgh (1790) and Oxford (1796) in Great Britain. Meanwhile. in France and Germany, Albrecht Thaer, S.F. Hermstadt, Jean-Baptiste Boussingault. and, in particular, Justus von Liebig were laying the foundations of agricultural research...[3]

As Harro Maat (2001) stated:

- King William I... realised new legislation for higher education... [which provided] chairs in land-household studies (landhuishoudkunde) in the faculty of Physics and Natural Science. Jan Kops occupied the chair in land-household studies at the University of Utrecht In Leiden it was Christiaan F. Kleijnhoff van Enspijk (1761-1819) and Jacobus A. Uilkens (1772-1825) was appointed as professor in landhousehold studies at the University of Groningen. The designation landhousehold studies (landhuishoudkunde), was the rural version of state-household studies (staathuishoudkunde) and both areas had a background in statistics and economy. Land-household studies, however, was not just about the economic principles of agriculture, but also covered chemistry, natural history and physics. With the installation of these professors, agrarian issues had a place in the Dutch university system. Entrance to a university, however, required a schooling track that was rather costly and very few farmers could afford to send their sons to one of the academies. Therefore a connection had to be made between the university lectures and the practising farmers[13]

- ... The chairs in land-household studies, installed at the Dutch universities in 1815, were the first formally arranged facility for the development of agricultural science..."

Programs to considered agriculture as a science[edit]

In the 19th century Specialized books, magazines, newspapers started to occur. Scientists started proposing programs to considered agriculture as a science inaugurated the scientific approach in agriculture.

In 1825 Loudon (1825, p. 208) postulated the following chapter about "Agriculture considered as a science" referring to the work of Albrecht Thaer.

- 1259. All knowledge is founded on experience; in the infancy of any art, experience is confined and knowledge limited to a few particulars ; but as arts are improved and extended a great number of facts become known, and the generalization of these, or the arrangement of them according to some leading principle, constitutes the theory, science, or law of an art.

- 1260. Agriculture, in common with other arts, may be practised without any knowledge of its theory ; that is, established practices may be imitated ; but in this case it must ever remain stationary. The mere routine practitioner cannot advance beyond the limits of his own particular experience, and can neither derive instruction from such accidents as are favorable to his object, nor guard against the recurrence of such as are unfavorable. He can have no resource for unforeseen events but ordinary expedients ; while the man of science resorts to general principles, refers events to their true causes, and adapts his measures to meet every case.

- 1261. The object of the art of agriculture is to increase the quantity and improve the quality of such vegetable and animal productions of the earth as are used by civilized man ; and the object of the agriculturist is to do this with the least expenditure of means ; or, in other words, with profit. The result of the experience of mankind as to other objects may be conveyed to an enquiring mind in two different ways : he may be instructed in the practical operations of the art, and their theory, or the reasons on which they are founded, laid down and explained to him as he goes along ; or he may be first instructed in general principles, and then in the practices which flow from them. The former mode is the natural or actual mode in which every art is acquired (in so far as acquirement is made) by such as have no recourse to books, and may be compared to the natural mode of acquiring a language without the study of its grammar. The latter mode is by much the most correct and effectual, and is calculated to enable an instructed agriculturist to proceed with the same kind of confidence and satisfaction in his practice that a grammarian does in the use of language.

- 1262, In adopting what we consider as the preferable mode of agricultural instruction, we shall, as its grammar or science, endeavour to convey a general idea of the nature of vegetables, of animals, of minerals, mixed bodies, and the atmosphere, as connected witli agriculture ; of agricultural implements and other mechanical agents ; and of agricultural operations and processes.

- 1263. The study of the science of agriculture may be considered as implying a regular education in the student, who ought to be well acquainted with arithmetic and mensuration, have acquired the art of sketching objects, whether animal, vegetable, or general scenery, of taking off, and laying down geometrical plans ; but especially he ought to have studied chemistry, hydraulics, and something of carpentry, smithery, and the other building arts : and as Professor Von Thaer observes, he ought to have some knowledge of all those manufactures to which his art furnishes the raw materials.[14]

Harro Maat (2001) confirms the role of Justus von Liebig and further explains this role:

- Land-household studies, as lectured by Kops and the other professors, can be characterised as a descriptive science, based in the classical approach of statistics. The lectures contained overviews and comparisons about different modes of farming, details about the taxonomic features of crops and the chemical substances they contain. Innovation was based on experiments in the field with methods, plants or tools, copied from elsewhere...[15]

Provincial agricultural societies[edit]

Harro Maat (2001) about the Netherlands:

- During the 1840s prominent figures in the rural and urban society founded provincial agricultural societies in order to defend the interests of farmers and support progress in agriculture... [16]

In 1838 the British Science Association announced the new section for Agricultural Science.

- It is with much pleasure that I hail the notice of Dr. Granville for the formation, at the next meeting of the British Association at Birmingham, of a section for the promotion of scientific agricultural researches, an idea which was, I believe, first started by Earl Fitzwilliam at one of the English Agricultural Society's meetings, with which society the new section of agricultural science will in no way interfere, since the Society is adapted for other objects—will be, evidently, a kind of locomotive Smithfield Cattle Shew, and Exhibition of Agricultural Instruments—they do not intend to make any scientific movements, not having a single person on the committee of management except Mr. Youatt, the eminent veterinary surgeon, who has the slightest knowledge of science...[17]

In 1842 also in London James Allen Ransome and William Shaw (1797-1853) founded the Farmers Club.

Modern agricultural science[edit]

Foundation[edit]

Harro Maat (2001) confirms the role of Justus von Liebig and further explains this role:

- From the 1830s a new approach to phenomena in nature and agriculture came up, most prominently in chemistry and biology. The leading figures in the new approach were Justus von Liebig (1803-1873) and Charles Darwin (1809-1882)... Justus von Liebig is generally seen as the founding father of modern agricultural science and the main pioneer in organic chemistry. Von Liebig openly attacked the traditional ways of experimentation in organic chemistry in general and its application to agriculture in particular He accused traditional chemists and physiologists of conducting experiments that were valueless for the decision of any question because performed without any idea what the range of the experiment was. According to Liebig a proper experiment required a theory that provided insight in the conditions under which a hypothesis could be rejected or accepted.[18]

The Encyclopedia Britannica (2014):

- The scientific approach was inaugurated in 1840 by Justus von Liebig of Darmstadt, Germany. His classic work, Die organische Chemie in ihrer Anwendung auf Agrikulturchemie und Physiologie (1840; Organic Chemistry in Its Applications to Agriculture and Physiology), launched the systematic development of the agricultural sciences... [1]

Will Thomas (2010) summarizes:

- The importance of agricultural research in the intellectual history of science should be self-evident. Justus Liebig (1803-1873) was a key figure in both the development of laboratory methodology and agricultural science. Gregor Mendel’s (1822-1884) famous experiments were in plant breeding. Louis Pasteur’s (1822-1895) most celebrated work was on the cattle disease, anthrax. William Bateson (1861-1926), who coined the term genetics, was the first director of the John Innes Horticultural Institution in London, 1910-1926. Statistician, geneticist, and eugenics proponent R. A. Fisher (1890-1962) was employed by the Rothamsted Experimental Station, 1919 to 1933 (and temporarily relocated there from 1939 to 1943). Interwar and postwar virologists and molecular biologists did a great deal of work on the economically destructive tobacco mosaic virus.[19]

Current Wikipedia entry on History of agricultural science

- Agricultural science began with Gregor Mendel's genetic work, but in modern terms might be better dated from the chemical fertilizer outputs of plant physiological understanding in eighteenth century Germany...

Agricultural research[edit]

The Rothamsted Experimental Station was founded in 1843 by John Bennet Lawes on his inherited 16th century estate, Rothamsted Manor, to investigate the impact of inorganic and organic fertilizers on crop yield. Lawes, a noted Victorian era entrepreneur and scientist, had founded one of the first artificial fertilizer manufacturing factories one year earlier in 1842.

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica (1998) further stipulated:

- In England, Rothamsted Experimental Station, the oldest research centre in continuous operation, and the Royal Agricultural College at Cirencester started before 1850. But probably the key date in the history of agricultural research and education is 1862, when the U.S. Congress set up the Department of Agriculture...[3]

Agricultural science studies[edit]

The Encyclopedia Britannica (2014):

- [In the second half of the 19th century] In Europe, a system of agricultural education soon developed that comprised secondary and postsecondary instruction. The old empirical-training centres were replaced by agricultural schools throughout Europe and North America. Under Liebig’s continuing influence, academic agriculture came to concentrate on the natural sciences...[1]

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica (1998) continues:

- ... Probably the key date in the history of agricultural research and education is 1862, when the U.S. Congress set up the Department of Agriculture and provided for colleges (many now incorporated in state universities) of agricultural and mechanical arts in each state.[3]

Contemporary[edit]

Agronomy and the related disciplines of agricultural science today are very different from what they were before about 1950. Intensification of agriculture since the 1960s in developed and developing countries, often referred to as the Green Revolution, was closely tied to progress made in selecting and improving crops and animals for high productivity, as well as to developing additional inputs such as artificial fertilizers and phytosanitary products.

However, environmental damage due to intensive agriculture, industrial development, and population growth have raised many questions among agronomists and have led to the development and emergence of new fields (e.g., integrated pest management, waste treatment technologies, landscape architecture, genomics).

New technologies, such as biotechnology and computer science (for data processing and storage), and technological advances have made it possible to develop new research fields, including genetic engineering, improved statistical analysis, and precision farming.

The study of the history of agricultural science[edit]

New lead of the History of agricultural science Wikipedia article:

- History of agricultural science studies the scientific advancement of techniques and understanding of agriculture.

Will Thomas (2010) made multiple observations:

- The history of agricultural research itself remains somewhat difficult to discern, even though it apparently constitutes a long, sizable tradition. We do have some enumeration of accomplishments in research and technique, written in retrospect by practitioners. For the case of the UK, the following resources are available:

- Daniel Hall’s, Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: Essays on Research, Practice, and Organization (1939)

- E. John Russell’s A History of Agricultural Science in Great Britain: 1620-1954 (1966)

- G. W. Cooke’s Agricultural Research, 1931-1981 (UK Agricultural Research Council, 1981)

- Kenneth Blaxter and Noel Robertson’s From Dearth to Plenty: The Modern Revolution in Food Production (1995)..

- There is a significant literature on other countries’ agricultural science...

- There is a very heavy emphasis in the literature on plant breeding, seemingly drawn toward the twin poles of the rise of genetics at the beginning of the 20th-century, and the rise of bio-engineering at its end...

- Policy history is a third area that, despite Olby’s political histories, seems detached from the science historiography except insofar as policy is taken to comprise a successful or unsuccessful dirigisme of scientific breeding — though...

- It is not clear to me that the relationship between research and advice, state regulation, market action, and the choices of individual farmers is well worked out, nor is it clear to me that these histories have been given their proper independence from each other given interest in locating the inevitable tensions between them...[19]

Other notable scientists mentioned by Thomas (2010) are Paul Brassley, Margaret Rossiter, Paolo Palladino, Jonathan Harwood, Barbara Kimmelman, Jack Ralph Kloppenburg, Deborah Fitzgerald, Thomas Wieland, Susanne Heim, Christophe Bonneuil, Jean-Luc Mayaud, Robert Olby, William Bateson, Marsha L. Richmond, and Abigail Woods.

As to the organization:

- The Agricultural History Society was founded in Washington, DC in 1919 "to promote the interest, study and research in the history of agriculture." Incorporated in 1924, the Society began publishing a journal, Agricultural History, in 1927.[20]

Themes in the history of agricultural science[edit]

Genetics[edit]

A genetic study of Agricultural science began with Gregor Mendel's work. Mendel developed the model of Mendelian inheritance which accurately described the inheritance of dominant and recessive genes. His results were controversial at the time and were not widely accepted until the 20th century.

Fertilizer[edit]

Johann Friedrich Mayer was the first scientist to publish experiments on the use of gypsum as a fertilizer, but the mechanism that made it function as a fertilizer was contested by his contemporaries.[21]

The development of Liebig's law of the minimum, which states that growth occurs as quickly as the greatest limiting factor, helped give an understanding of when crops would prosper.

In the United States, a scientific revolution in agriculture began with the Hatch Act of 1887, which used the term "agricultural science". The Hatch Act was driven by farmers' interest in knowing the constituents of early artificial fertilizer. Later on, the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 shifted agricultural education back to its vocational roots, but the scientific foundation had been built.[22] After 1906, public expenditures on agricultural research in the US exceeded private expenditures for the next 44 years.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g "Agricultural science" lemma on the Encyclopedia Britannica online, 2014

- ^ a b Loudon (1825, p. 47)

- ^ a b c d The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Vol 1 (1998). p. 156

- ^ Russell, E. John. "A history of agricultural science in Great Britain, 1620-1954." A History of Agricultural Science in Great Britain, 1620-1954. (1966): Review at cabdirect.org

- ^ Ephraim Chambers (1741, p. 143)

- ^ John Claudius Loudon (1825) An Encyclopædia of Agriculture. p. 8

- ^ Loudon (1825, p. 12)

- ^ Walter Harte. Essays on husbandry. 1764.

- ^ Loudon (1825, p. 41)

- ^ Alfred Charles True A History of Agricultural Education in the United States, 1785-1925 (1929) p. 6

- ^ Harro Maat (2003) Science Cultivating Practice: A History of Agricultural Science in The Netherlands and its Colonies, 1863–1986. at edepot.wur.nl, p. 39

- ^ Jean Bérenger. A History of the Habsburg Empire: 1700-1918. Longman, 1997. p. 78

- ^ Harro Maat (2001, p. 40-41)

- ^ Loudon (1825, p. 208)

- ^ Maat (2001, p. 42)

- ^ Harro Maat (2001, p. 44)

- ^ "The British Association" in: British Farmer's Magazine, Volume 2. 1838, p. 402

- ^ Maat (2001, p. 42-43)

- ^ a b Will Thomas (2010) "Preliminary Survey: Literature on Agricultural Research to 1945" at etherwave.wordpress.com, 2010/11/19

- ^ The Agricultural History Society

- ^ John Armstrong, Jesse Buel. A Treatise on Agriculture, The Present Condition of the Art Abroad and at Home, and the Theory and Practice of Husbandry. To which is Added, a Dissertation on the Kitchen and Fruit Garden. 1840. p. 45.

- ^ Hillison J. (1996). The Origins of Agriscience: Or Where Did All That Scientific Agriculture Come From?. Journal of Agricultural Education.

- ^ Huffman WE, Evenson RE. (2006). Science for Agriculture. Blackwell Publishing.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from John Claudius Loudon (1825) An Encyclopædia of Agriculture. ; and other public domain material from books and/or websites, see article history.

This article incorporates public domain material from John Claudius Loudon (1825) An Encyclopædia of Agriculture. ; and other public domain material from books and/or websites, see article history.

Further reading[edit]

- Paul Brassley. "Agricultural Research in Britain, 1850-1914: failure, success, and development," Annals of Science 52 (1995): 465-480.

- Alfred Daniel Hall. Agriculture in the Twentieth Century: Essays on Research, Practice, and Organization (1939)

- Walter Harte. Essays on husbandry. 1764.

- John Claudius Loudon. An Encyclopædia of Agriculture. 1825.

- Harro Maat. Science Cultivating Practice: A History of Agricultural Science in The Netherlands and its Colonies, 1863–1986. at edepot.wur.nl, 2003.

- Margaret Rossiter. The Emergence of Agricultural Science: Justus Liebig and the Americans, 1840-1880. 1975.

- Edward John Russell. A History of Agricultural Science in Great Britain, 1620-1954. 1966

- Alfred C. True. History of Agricultural Education in the United States, 1785-1925,