User:Jim62sch/nos

Template:Featured article is only for Wikipedia:Featured articles.

Nostradamus (December 14, 1503 – July 2, 1566), born Michel de Nostredame[1], was one of the world's most famous authors of prophecies. He is best known for his book Les Propheties, which consists of one unrhymed and 941 rhymed quatrains, grouped into nine sets of 100 and one of 42, called "Centuries".

Since the time of publication of the book a virtual cult has grown around Nostradamus and his Propheties. He has been credited with predicting a number of historical events, yet the interpretations of his writings in this way often prove to take liberties either with the original text, or with the events themselves. To date, no one is known to have succeeded in using any specific quatrain to predict any particular event in advance.[2]

Interest in the work of this prominent figure of the French Renaissance is nevertheless still considerable, especially in the media and in popular culture, and the prophecies have in some cases been assimilated to the results of applying the alleged Bible Code, as well as to other purported prophetic works.

Biography[edit]

Childhood[edit]

Born in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in the south of France in December 1503, where his claimed birthplace still exists, Michel de Nostredame was one of at least eight children of Reynière de St-Rémy and grain dealer and notary Jaume de Nostredame. The latter's family had originally been Jewish, but Jaume's father, Guy Gassonet, had converted to Catholicism circa 1455, taking the Christian name "Pierre" and the surname "Nostredame" (French for "Our Lady", since his conversion was solemnized on a feast of the Virgin Mary).[3]

His known siblings included Delphine, Jehan (c. 1507–77), Pierre, Hector, Louis (b. 1522), Bertrand, Jean and Antoine (b. 1523). [3] [4] [2]

Student years[edit]

Little else is known about Nostredame's childhood, although there is a persistent tradition that he was educated by his maternal great-grandfather Jean de St-Rémy[5] — which is vitiated by the equally persistent tradition that the latter died when the child was only one year old.[6] It is known, however, that at the age of fifteen Nostredame entered the University of Avignon to study for his baccalaureate. After little more than a year (when he would have studied the regular Trivium of grammar, rhetoric and logic, rather than the later Quadrivium of geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy/astrology), he was forced to leave Avignon when the university closed its doors in the face of an outbreak of the plague. In 1529, after some years as an apothecary, he entered the University of Montpellier to study for a doctorate in medicine. He was expelled again shortly afterwards when it was discovered that he had been an apothecary, which was a "manual" trade expressly banned by the university statutes. The handwritten expulsion document (BIU Montpellier, Register S 2 folio 87) still exists in the faculty library.[2] After his expulsion Nostredame continued working, presumably as an apothecary (though some of his publishers and correspondents would later call him "Doctor"), and became famous for creating a "rose pill" that was widely believed (not least by himself) to protect against the plague.[7]

Marriage and healing work[edit]

In 1531 he was invited by Jules-César Scaliger, a leading Renaissance scholar, to come to Agen.[3] There Nostredame married a woman whose name is still in dispute (possibly Henriette d'Encausse), who bore him two children.[8] In 1534, however, his wife and children died, presumably from the Plague. After their death he continued to travel, passing through France and possibly Italy.[3]

On his return in 1545, he assisted the prominent physician Louis Serre in his fight against a major plague outbreak in Marseille, and then tackled further outbreaks of disease on his own in Salon-de-Provence and in the regional capital, Aix-en-Provence. Finally, in 1547 he settled down in Salon-de-Provence in the house which is still there today, where he married a rich widow named Anne Ponsarde (nicknamed Gemelle, or "Twinny") and eventually had six children — three daughters (Madeleine, Anne and Diane) and three sons (César, Charles and André).[3] Between 1556 and 1567, Nostredame and his wife would in due course acquire a one-thirteenth share in a huge canal project organized by Adam de Craponne to irrigate largely waterless Salon and the nearby Désert de la Crau from the river Durance[6]. Parts of the network remain today: thanks to much larger supplementary canals, there is even a hydroelectric station in Salon itself.[2]

The seer[edit]

After a further visit to Italy, Nostredame began to move away from medicine and towards the occult. Following popular trends, he wrote an almanac for 1550, for the first time Latinizing his name to Nostradamus. He was so encouraged by its success that he decided to write one or more annually. Taken together, they are known to have contained at least 6,338 prophecies[9] (most of them, in the event, failed predictions)[2], as well as at least eleven annual calendars, all of them starting on January 1 and not, as is sometimes supposed, in March. It was mainly in reaction to the almanacs that the nobility and other prominent persons from far and wide soon started asking for horoscopes and advice from him, though he generally expected his clients to supply the birth charts on which the horoscopes would be based, contrary to the normal practice of professional astrologers.[6][4]

He then began his project of writing a book of one thousand quatrains, which constitute the largely undated prophecies for which he is most famous today. Feeling vulnerable to religious fanatics, however, he devised a method of obscuring his meaning by using "Virgilianized" syntax, word games and a mixture of languages such as Provençal, Greek, Latin and Italian. For technical reasons connected with their publication in three installments (the publisher of the third and last installment seems to have been unwilling to start it in the middle of a "Century", or book of 100 verses), the last fifty-eight quatrains of the seventh "Century" have not survived into any extant edition.

The quatrains, published in a book titled Les Propheties (The Prophecies), received a mixed reaction when they were published. Some people thought Nostradamus was a servant of evil, a fake, or insane, while many of the elite thought his quatrains were spiritually inspired prophecies — as, in the light of their postbiblical sources (see under Methods below), Nostradamus himself was indeed prone to claim. Catherine de Médicis, the queen consort of King Henri II of France, was one of Nostradamus' greatest admirers. After reading his almanacs for 1555, which hinted at unnamed threats to the royal family, she summoned him to Paris to explain them and to draw up horoscopes for her children. At the time, he feared that he would be beheaded, but by the time of his death in 1566, Catherine had made him Counselor and Physician-in-Ordinary to the King.

Some biographical accounts of Nostradamus' life state that he was afraid of being persecuted for heresy by the Inquisition, but neither prophecy nor astrology fell under this bracket, and he would have been in danger only if he had practiced magic to support them. In fact, his relations with the Church as a prophet and healer were always excellent. His brief imprisonment at Marignane in late 1561 came about purely because he had published his 1562 almanac without the prior permission of a bishop, contrary to a recent royal decree.

Final years and death[edit]

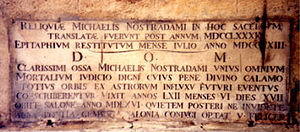

By 1566 Nostradamus' gout, which had plagued him painfully for many years and made movement very difficult, turned into dropsy. In late June he summoned his lawyer to draw up an extensive will bequeathing his property plus 3,444 crowns (around $300,000 today) — minus a few debts — to his wife pending her remarriage, in trust for her sons pending their twenty-fifth birthdays and her daughters pending their marriages. This was followed by a much shorter codicil.[3] On the evening of July 1, he is alleged to have told his secretary Jean de Chavigny, "You will not find me alive by sunrise." The next morning he was reportedly found dead, lying on the floor next to his bed and a bench (Presage 141 [originally 152] for November 1567, as posthumously edited by Chavigny to fit). [9][2] He was buried in the local Franciscan chapel (part of it now incorporated into the restaurant La Brocherie), but re-interred in the Collégiale St-Laurent at the French Revolution, where his tomb remains to this day. [3] His epitaph translates: "Here lie the bones of the illustrious Michael Nostradamus, whose almost divine pen alone, in the judgment of all mortals, was worthy to record, under the influx of the stars, the future events of the whole world. He lived 62 years, 6 months, 17 days. He died at Salon in the year 1566. Posterity, disturb not his sweet rest! Anne Ponce Gemelle hopes for her husband true felicity."

Methods[edit]

Nostradamus claimed to base his predictions on judicial astrology — the assessment of the "astrological quality" of expected future events — but was heavily criticized by professional astrologers of the day such as Laurens Videl[2] for his incompetence and for assuming that "comparative horoscopy" (comparison of future planetary configurations with the astrology of known past events) could predict the actual events themselves.[6]

Recent research has suggested that most of his prophetic work was in fact based on paraphrasing collections of ancient end-of-the-world prophecies (mainly Bible-based — the end of the world was expected at the time to occur in either 1800 or 1887, or possibly in 2242, depending on the system adopted) and supplementing their insights by projecting known historical events and identifiable anthologies of omen-reports into the future with the aid of comparative horoscopy. It is thanks to this that his work contains so many predictions involving ancient figures such as Sulla, Gaius Marius, Nero, Hannibal and so on, as well as descriptions of "battles in the clouds" and "frogs falling from the sky". Astrology itself is mentioned only twice in Nostradamus' Preface, and 41 times in the Centuries themselves, though rather more in his famously baffling dedicatory Letter to King Henri II.

His historical sources include easily identifiable passages from Livy, Suetonius, Plutarch and a range of other classical historians, as well as from the chronicles of medieval authors such as Villehardouin and Froissart. Many of his broader astrological references, by contrast, are taken almost word for word from the Livre de l'estat et mutations des temps of 1549–50 by Richard Roussat. Even the planetary tables, already published by professional astrologers, on which he based the birth charts that he was unable to avoid preparing himself are easily identifiable by their detailed figures, even where (as is usually the case) he gets some of them wrong. (Refer to the seminal analysis of these charts by Brind'Amour, 1993,[6] and compare Gruber's comprehensive critique of Nostradamus’ horoscope for Crown Prince Rudolph Maximilian.)[10]

His major prophetic source was evidently the Mirabilis liber of 1522, which contained a range of prophecies by Pseudo-Methodius, the Tiburtine Sibyl, Joachim of Fiore, Savonarola and others. (His Preface contains no fewer than 24 biblical quotations, all but two of them in exactly the same order as Savonarola.)[11] The book had enjoyed considerable success in the 1520s, when it went through half a dozen editions (see Links below for facsimiles and translations). The obvious question — why the Mirabilis liber did not sustain its influence in the way that Nostadamus’ writings did — is explained mainly by the fact that the book (like the Bible) was mostly in Latin and in Gothic script and, to make matters even more complicated for the general reader, contained many abstruse scholastic abbreviations. Nostradamus was, in effect, one of the first to present his prophecies (and others) openly in the French vernacular, as was also happening to the Bible at the time, which is no doubt why he has retained all the credit for them. The Mirabilis liber itself (some of whose predictions had already lapsed by the time Nostradamus started writing) was not translated into French until 1831, and this mainly for scholarly and antiquarian reasons at a time when knowledge of Latin was beginning to die out.

Meanwhile, if Nostradamus' critics — and he had many — never accused him of copying from it, it was because copying or paraphrasing, far from being regarded (as it is today) as mere plagiarism, was regarded at the time as what all good, educated people should do anyway. The whole Renaissance was based on the idea. Copying from the classics in particular, often without acknowledgement, and preferably from memory, was all the rage.[12] Only in the 17th century did people start to be surprised by the fact that much of his output was evidently based on earlier and often classical originals – anonymous letters to the Mercure de France in August and November 1724 drew specific public attention to the fact[13] – which was no doubt why, according to the early commentator Théophile de Garencières, his Prophecies started to be used as a classroom-reader at that time.[14]

Nostradamus, it should be remembered, denied in writing on several occasions that he was a prophet on his own account. In translation:

Although, my son, I have used the word prophet, I would not attribute to myself a title of such lofty sublimity —Preface to César, 1555

Not that I would attribute to myself either the name or the role of a prophet —Preface to César, 1555

[S]ome of [the prophets] predicted great and marvelous things to come: [though] for me, I in no way attribute to myself such a title here. —Letter to King Henri II, 1558

I do but make bold to predict (not that I guarantee the slightest thing at all), thanks to my researches and the consideration of what judicial Astrology promises me and sometimes gives me to know, principally in the form of warnings, so that folk may know that with which the celestial stars do threaten them. Not that I am foolish enough to pretend to be a prophet. —Open letter to Privy Councillor (later Chancellor) Birague, 15 June 1566

This last is presumably why he entitled his book Les Propheties de M. Michel Nostradamus, which in French can mean either "The Prophecies, by M. Michel Nostradamus" (which is precisely what they were) as "The Prophecies of M. Michel Nostradamus", which, except in a few cases, they were not, other than in the manner of their editing, expression and reapplication to the future.) Any criticism of Nostradamus for claiming to be a prophet, in other words, would have been for doing what he never claimed to be doing in the first place.

Further material was gleaned from the De honesta disciplina of 1504 by Petrus Crinitus,[6] which included extracts from Michael Psellus's De daemonibus, and the De Mysteriis Aegyptiorum..." (Concerning the mysteries of Egypt...), a book on Chaldean and Assyrian magic by Iamblichus, a 4th-century Neo-Platonist. Latin versions of both had recently been published in Lyon, and extracts from both are paraphrased (in the second case almost literally) in his first two verses. While it is true that Nostradamus claimed in 1555 to have burned all the occult works in his library, no one can say exactly what books were destroyed in this fire. The fact that they reportedly burned with an unnaturally brilliant flame suggests, however, that some of them were manuscripts on vellum, which was routinely treated with saltpeter.

Given that his methodology, clearly, was mainly literary, it is doubtful whether Nostradamus used any particular methods for entering a trance state, other than contemplation, meditation and incubation (i.e., ritually "sleeping on it"). His sole description of this process is contained in letter 41[15]of his collected Latin correspondence, as republished by Jean Dupèbe and translated by Lemesurier.[2] The popular legend that he attempted the ancient methods of flame gazing, water gazing or both simultaneously is based on an uninformed reading of his first two verses (see above), which merely liken his own efforts to those of the Delphic and Branchidic oracles. In his dedication to King Henri II, Nostradamus describes "emptying my soul, mind and heart of all care, worry and unease through mental calm and tranquility", but his frequent references to the "bronze tripod" of the Delphic rite are usually preceded by the words "as though".

Works[edit]

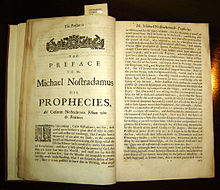

The Prophecies. In this book he collected his major, long-term divinations. The first installment was published in 1555. The second, with 289 further prophetic verses, was printed in 1557. The third edition, with three hundred new quatrains, was reportedly printed in 1558, but nowadays only survives as part of the omnibus edition that was published after his death in 1568. Given printing practices at the time (which included type-setting from dictation), no two editions turned out to be identical, and it is relatively rare to find even two copies that are exactly the same. Certainly there is no warrant for assuming – as would-be "code-breakers" are prone to – that either the spellings or the punctuation of any edition are Nostradamus' originals.[6]

The Almanacs. By far the most popular of his works, these were published annually from 1550 until his death. Often he published two or even three in a single year, entitled either Almanachs (detailed predictions), Prognostications or Presages (more generalized predictions).

Nostradamus was not only a diviner, but a professional healer, too. We know that he wrote at least two books on medical science. One was an alleged "translation" of Galen, and in his so-called Traité des fardemens (basically a medical cookbook containing, once again, materials borrowed mainly from others), he included a description of the methods he used to treat the plague — none of which (not even the bloodletting) apparently worked. The same book also describes the preparation of cosmetics.

A manuscript normally known as the Orus Apollo also exists in the Lyon municipal library, where upwards of 2,000 original documents relating to Nostradamus are stored under the aegis of Michel Chomarat. It is a purported translation of an ancient Greek work on Egyptian hieroglyphs based on later Latin versions, all of them unfortunately ignorant of the true meanings of the ancient Egyptian script, which was not correctly deciphered until the advent of Champollion in the 19th century.

Since his death only the Prophecies have continued to be popular, but in this case they have been quite extraordinarily so. Indeed, they have seldom, if ever, been out of print. This may be due partly to popular unease about the future, partly to people's desire to see their lives in some kind of overall cosmic perspective and so to give meaning to them — but above all, possibly, to their vagueness and lack of dating, which enables them to be wheeled out after every major dramatic event and retrospectively claimed as "hits".

The role of interpretation[edit]

Nostradamus enthusiasts have credited him with predicting numerous events in world history, including the French Revolution, the atomic bomb, the rise of Adolf Hitler, the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and even the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Indeed, they regularly make similar claims regarding each new world crisis as it comes along, following the persistent tendency to claim that "Nostradamus predicted whatever has just happened".[10]

Nostradamus does not in fact mention any of the above specifically, not even Hitler: the name Hister, as he himself explains in his Presage for 1554, is merely the classical name for the Lower Danube, while Pau, Nay, Loron — often claimed to be an anagram of "Napaulon Roy"— evidently refers simply to three neighboring towns in southwestern France close to the seer's onetime home territory. Such typical popular pieces of linguistic sleight of hand are particularly easy to carry out when the would-be commentator knows no French to start with, especially in its 16th-century form — to say nothing of French geography. Not surprisingly, then, detractors see such "edited" predictions as examples of vaticinium ex eventu, retroactive clairvoyance and selective thinking, which find nonexistent patterns in ambiguous statements. Because of this it has been claimed that Nostradamus is "100% accurate at predicting events after they happen", while the seer has acquired even more disrepute than he possibly deserves.[2]

Skeptics of Nostradamus state that his reputation as a prophet is largely manufactured by modern-day supporters who shoehorn his words into events that have either already occurred or are so imminent as to be inevitable, a process known as "retroactive clairvoyance". A good demonstration of this flexible predicting is to take lyrics written by modern songwriters (e.g., Bob Dylan) and show that they are equally "prophetic". (For Dylan see Masters Of War, As I Went Out One Morning, Gates Of Eden, A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall,It's Alright, Ma [I'm Only Bleeding], etc.) It has been stated, probably correctly, that no Nostradamus quatrain has ever been interpreted as predicting a specific event before it occurred beyond a very general level (e.g., a fire will occur, a war will start).[2]

Some scholars believe that Nostradamus wrote not to be a prophet, but to comment on events that were happening in his own time, writing in his elusive way — using highly metaphorical and cryptic language — in order to avoid persecution. This is similar to the Preterist interpretation of the Book of Revelation: according to this, John (the Divine) intended to write only about contemporary or immediately impending events ('Yes, I am coming soon' [22:20]), but over time his writings, too, came to be seen as long-term prophecies.[2]

The bulk of the quatrains deal with disasters of various sorts (nearly all of them undated). These include plagues, earthquakes, wars, floods, invasions, murders, droughts, battles and many other related events — all of them as foreshadowed by the Mirabilis liber. Some quatrains cover these in overall terms; others concern a single person or small group of persons. Some cover a single town, others several towns in several countries. A major, underlying theme is an impending invasion of Europe by Muslim forces from further east and south headed by the expected Antichrist, directly reflecting the then-current Ottoman invasions and the earlier Saracen equivalents, as well as the prior expectations of the Mirabilis liber. All of this is presented in the context of the supposedly imminent end of the world, a conviction that sparked numerous collections of end-time prophecies at the time, not least an unpublished collection by Christopher Columbus.[16]

Nostradamus in popular culture[edit]

- Main article: Nostradamus in popular culture

The prophecies of the 16th-century author Nostradamus have been a part of popular culture in the 20th and 21st centuries. As well as being the subject of hundreds of books (both fiction and nonfiction), Nostradamus' life has been depicted in several films and videos, and his life and prophecies continue to be a subject of media interest. In the internet age, there have also been several well-known hoaxes, where quatrains in the style of Nostradamus have been circulated by e-mail as the real thing. The best-known examples concern the collapse of the World Trade Center in the attacks of September 11, 2001, which led both to hoaxes and to reinterpretations by enthusiasts of several quatrains as supposed prophecies. As stated above, other well-known Nostradamus prophecies have been twisted to "predict", for example, the rise of Hitler (the reference is in fact to Hister, the classical name for the Lower Danube).

The September 11, 2001, attacks on New York City led to immediate speculation as to whether Nostradamus had predicted the events (and more than one outright hoax, circulated by e-mail). Almost as soon as the event had happened, the relevant Internet sites were deluged with enquiries into whether Nostradamus had predicted the event. In response, Nostradamus enthusiasts started searching for at least one Nostradamus quatrain that could be said to have done so, coming up with new interpretations of Quatrains VI.97 and I.87. However, the various ways in which the enthusiasts chose to interpret the text were almost universally panned by experts on the subject (compare the relevant sections of the Snopes and Lemesurier websites listed under External Links below).[10][2]

In this and other ways, the real Nostradamus has over the centuries become increasingly unknown, and the unknown Nostradamus "real", to the point where millions of perfectly rational people today believe only legends about him and, to the mystification of the actual scholars in the field, are reluctant to believe anything else — least of all that the real man used the real, and for the most part perfectly humdrum, techniques described above to arrive at predictions that are as vague and nonspecific as they actually are. In the words of Arthur C Clarke, "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."[17].

See also[edit]

- Astrology. For comparison with another predictive protoscience see Alchemy.

- List of astrologers.

- Divination

- Mysticism

- Vaticinia Nostradami

Sources[edit]

- Nostradamus, Michel:

- Orus Apollo, 1545 (?), unpublished ms; Almanachs, Presages and Pronostications, 1550-1567; Ein Erschrecklich und Wunderbarlich Zeychen..., Nuremberg, 1554; Les Propheties, Lyon, 1555, 1557, 1568; Traite des fardemens et des confitures, 1555, 1556, 1557; Paraphrase de C. Galen sus l'exhortation de Menodote, 1557; Lettre de Maistre Michel Nostradamus, de Salon de Craux en Provence, A la Royne mere du Roy, 1566

- Leroy, Dr Edgar, Nostradamus, ses origines, sa vie, son oeuvre, 1972 (the seminal biographical study)

- Dupèbe, Jean, Nostradamus: Lettres inédites, 1983

- Randi, James, The Mask of Nostradamus, 1993

- Rollet, Pierre, Nostradamus: Interprétation des hiéroglyphes de Horapollo, 1993

- Brind'Amour, Pierre: Nostradamus astrophile, 1993; Nostradamus. Les premières Centuries ou Prophéties, 1996

- Lemesurier, Peter, The Nostradamus Encyclopedia, 1997; The Unknown Nostradamus, 2003; Nostradamus: The Illustrated Prophecies, 2003

- Prévost, Roger, Nostradamus, le mythe et la réalité, 1999

- Chevignard, Bernard, Présages de Nostradamus 1999

- Wilson, Ian, Nostradamus: The Evidence, 2002

- Clébert, Jean-Paul, Prophéties de Nostradamus, 2003

- Gruber, Dr Elmar, Nostradamus: sein Leben, sein Werk und die wahre Bedeutung seiner Prophezeiungen, 2003

External links consistent with the article[edit]

- Timeline

- Facsimiles of original editions with translations

- Facsimiles of many contemporary texts

- Facsimiles, reprints and some translations of a huge range of Nostradamus texts, info etc.

- False claims of Nostradamus predicting the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001

- Lemesurier's FAQs and website

- Historical origins of the Propheties

- ESPACE NOSTRADAMUS Benazra's French website and major academic forum

- CURA's major international academic forum

- Online Nostradamus Library of original works in facsimile

- LOGODAEDALIA Scientific and Medical French website (Dr. Lucien de Luca)

- Anna Carlstedt (La poésie oraculaire de Nostradamus, 2005)

- Selected English translations from the Mirabilis liber.

- FAQ, mixed translations and illustrated tour of Nostradamus's Provence

Notes[edit]

- ^ Nostradamus (1999). Ned Halley (ed.). Complete Prophecies of Nostradamus. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited. pp. page xi. ISBN 1840223014.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lemesurier, Peter, The Unknown Nostradamus, 2003

- ^ a b c d e f g Leroy, Dr Edgar, Nostradamus, ses origines, sa vie, son oeuvre, 1972, ISBN 2862762318

- ^ a b Lemesurier, Peter, 'The Nostradamus Encyclopedia, 1997 ISBN 0312170939

- ^ Chavigny, J.A. de: La première face du Janus françois... (Lyon, 1594)

- ^ a b c d e f g Brind'Amour, Pierre, Nostradamus astrophile, 1993

- ^ Nostradamus, Michel, Traite des fardemens et des confitures, 1555, 1556, 1557

- ^ Maison de Nostradamus at Salon

- ^ a b Chevignard, Bernard, Présages de Nostradamus 1999

- ^ a b c Gruber, Dr Elmar, Nostradamus: sein Leben, sein Werk und die wahre Bedeutung seiner Prophezeiungen, 2003

- ^ SeeSavonarola and Nostradamus text comparison

- ^ Compare Rabelais's recommendation of critical, rather than rote learning in Gargantua I.23 (1534) and Pantagruel II.8 (1532), with all its implications for actually digesting, rather than merely regurgitating, what has been learned.

- ^ (Anonyme) Lettre critique sur la personne et sur les écrits de Michel Nostradamus, Mercure de France, août et novembre 1724 (Relève, dans un esprit rationaliste, des coïncidences entre certains quatrains des Prophéties et des évènements antérieurs à la publication de ces quatrains. Tout n'est pas également convaincant, mais on repoussera difficilement, par exemple, le rapprochement entre le quatrain VIII, 72 et le siège de Ravenne de 1512.)

- ^ Garencières, Théophile de: The true prophecies or prognostications of Michel Nostradamus, 1672.

- ^ See facsimile of letter

- ^ Watts. P.M., Prophecy and Discovery: On the Spiritual Origins of Christopher Culumbus's 'Enterprise of the Indies' in: American Historical Review, February 1985, pp. 73-102

- ^ Clarke, Arthur C., Profiles of the Future, Gollancz 1962, Pan 1964, rev. 1973, ISBN 0060107928, 'Clarke's Third Law', page 39