User:Barr Theo/sandbox1

International career[edit]

2004–2005: success at youth level[edit]

As a dual Argentine-Spanish national, Messi was eligible to play for the national team of both countries.[1] Selectors for Spain's Under-17 squad began pursuing him in 2003 after Barcelona's director of football, Carles Rexach, alerted the Royal Spanish Football Federation to their young player. Messi declined the offer, having aspired to represent La Albiceleste since childhood. To further prevent Spain from taking him, the Argentine Football Association organised two under-20 friendlies in June 2004, against Paraguay and Uruguay, with the purpose of finalising his status as an Argentina player in FIFA. Five days after his 17th birthday, on 29 June, he made his debut for his country against Paraguay, scoring once and providing two assists in their 8–0 victory. He was subsequently included in the squad for the South American Youth Championship, held in Colombia in February 2005. As he lacked the stamina of his teammates, the result of his former growth hormone deficiency, he was used as a substitute in six of the nine games. After being named man of the match against Venezuela, he scored the winning 2–1 goal in the crucial last match against Brazil, thereby securing their third-place qualification for the FIFA World Youth Championship.[2]

Aware of his physical limitations, Messi employed a personal trainer to increase his muscle mass, returning to the squad in an improved condition in time for the World Youth Championship, hosted by the Netherlands in June. After he was left out of the starting line-up in their first match against the United States, a 1–0 defeat, the squad's senior players asked manager Francisco Ferraro to let Messi start, as they considered him their best player. After helping the team defeat Egypt and Germany to progress past the group stage, Messi proved decisive in the knockout phase as he scored their equaliser against Colombia, provided a goal and an assist against title favourites Spain, and scored their opening goal against reigning champions Brazil. Ahead of the final, he was awarded the Golden Ball as the best player of the tournament. He scored two penalties in their 2–1 victory over Nigeria, clinching Argentina's fifth championship and finishing the tournament as top scorer with 6 goals.[3][4] His performances drew comparisons with compatriot Diego Maradona, who had led Argentina to the title in 1979.[4]

2005–2006: senior and World Cup debuts[edit]

In recognition of his achievements with the under-20 side, senior manager José Pékerman gave Messi his first call-up for a friendly against Hungary on 17 August 2005. Aged 18, Messi made his senior debut for Argentina in the Ferenc Puskás Stadium when he came on in the 63rd minute, only to be sent off after two minutes for a perceived foul against Vilmos Vanczák, who had grabbed his shirt; Messi had struck the defender with his arm while trying to shake him off, which the referee interpreted as an intentional elbowing, a contentious decision.[5] Messi was reportedly found weeping in the dressing room after his sending-off.[6] He returned to the team on 3 September in their World Cup qualifier defeat to Paraguay, which he had declared his "re-debut" ahead of the match.[7] Messi started his first game in the next qualifying match against Peru, in which he was able to win a crucial penalty that secured their victory. After the match, Pékerman described him as "a jewel".[8] He subsequently made regular appearances for the team ahead of Argentina's participation in the 2006 FIFA World Cup, scoring his first goal in a friendly against Croatia on 1 March 2006.[9] A hamstring injury sustained a week later jeopardised his presence in the World Cup, but he was nevertheless selected for Pékerman's squad and regained fitness in time for the start of the tournament.[10]

During the World Cup in Germany, Messi witnessed their opening match victory against the Ivory Coast from the substitutes' bench. In the next match, against Serbia and Montenegro, he became the youngest player to represent Argentina at a FIFA World Cup when he came on as a substitute in the 74th minute. He assisted their fourth strike within minutes and scored the final goal in their 6–0 victory, making him the youngest scorer in the tournament and the sixth-youngest goalscorer in the history of the World Cup.[11] As their progression to the knockout phase was secured, several starters were rested during the last group match. Messi consequently started the game against the Netherlands, a 0–0 draw, as they won their group on goal differential.[12][13] In the round of 16 match against Mexico, played on his 19th birthday, Messi came on in the 84th minute, with the score tied at 1–1. He appeared to score a goal, but it was contentiously ruled offside, with the team needing a late goal in extra time to proceed.[14][15] He did not play in the quarter-final against Germany, during which Argentina were eliminated 4–2 in a penalty shootout.[16] Back home, Pékerman's decision to leave him on the bench against Germany led to widespread criticism from those who believed Messi could have changed the outcome of the match in Argentina's favour.[17][18]

2007–2008: Copa América final and Olympic gold[edit]

As Messi evolved into one of the best players in the world, he secured a place in Alfio Basile's starting line-up, as part of a team considered favourites to win the 2007 Copa América, held in Venezuela.[19][20] He set up the game-winning goal of their 4–1 victory over the United States in the opening match, before winning a penalty that led to the game-tying first strike of their 4–2 win in the next match against Colombia.[21][22] At the quarter-final stage, where the group winners faced Peru, he scored the second goal of a 4–0 victory that saw them through to the semi-final, during which he chipped the ball over Mexico's goalkeeper to ensure another 3–0 win.[20] In a surprise defeat, Argentina lost the final 3–0 to a Brazil squad that lacked several of the nation's best players.[23] Their unexpected loss was followed by much criticism in Argentina, though Messi was mostly exempt due to his young age and secondary status to star player Juan Román Riquelme.[20] He was named the best young player of the tournament by CONMEBOL.[24]

Ahead of the 2008 Summer Olympics, Barcelona legally barred Messi from representing Argentina at the tournament as it coincided with their Champions League qualifying matches.[25] After interference from newly appointed Barcelona manager Pep Guardiola, who had won the tournament in 1992, Messi was permitted to join Sergio Batista's under-23 squad in Beijing.[26] During the first match, he scored the opening goal in their 2–1 victory over the Ivory Coast. Following a 1–0 win in the next group match against Australia, ensuring their quarter-final qualification, Messi was rested during the game against Serbia, while his side won the match to finish first in their group. Against the Netherlands, he again scored the first goal and assisted a second strike to help his team to a 2–1 win in extra time. After a 3–0 semi-final victory over Brazil, Messi assisted the only goal in the final as Argentina defeated Nigeria to claim Olympic gold medals.[27] Along with Riquelme, Messi was singled out by FIFA as the stand-out player from the tournament's best team.[28]

2008–2011: collective decline[edit]

From late 2008, the national team experienced a three-year period marked by poor performances.[20] Under manager Diego Maradona, who had led Argentina to World Cup victory as a player, the team struggled to qualify for the 2010 World Cup, securing their place in the tournament only after defeating Uruguay 1–0 in their last qualifying match. Maradona was criticised for his strategic decisions, which included playing Messi out of his usual position. In eight qualifying matches under Maradona's stewardship, Messi scored only one goal, netting the opening goal in the first such match, a 4–0 victory over Venezuela.[9][29] During that game, played on 28 March 2009, he wore Argentina's number 10 shirt for the first time, following the international retirement of Riquelme.[30] Overall, Messi scored four goals in 18 appearances during the qualifying process.[9] Ahead of the tournament, Maradona visited Messi in Barcelona to request his tactical input; Messi then outlined a 4–3–1–2 formation with himself playing behind the two strikers, a playmaking position known as the enganche in Argentine football, which had been his preferred position since childhood.[31]

Despite their poor qualifying campaign, Argentina were considered title contenders at the World Cup in South Africa. At the start of the tournament, the new formation proved effective; Messi managed at least four attempts on goal during their opening match but was repeatedly denied by Nigeria's goalkeeper, resulting in a 1–0 win. During the next match, against South Korea, he excelled in his playmaking role, participating in all four goals of his side's 4–1 victory. As their place in the knockout phase was guaranteed, most of the starters were rested during the last group match, but Messi reportedly refused to be benched.[29] He wore the captain's armband for the first time in their 2–0 win against Greece; as the focal point of their play, he helped create their second goal to see Argentina finish as group winners.[32]

Argentina were eliminated in the quarter-final against Germany, at the same stage of the tournament and by the same opponent as four years earlier. Their 4–0 loss was their worst margin of defeat at a World Cup since 1974.[33] FIFA subsequently identified Messi as one of the tournament's 10 best players, citing his "outstanding" pace and creativity and "spectacular and efficient" dribbling, shooting and passing.[34] Back home, however, Messi was the subject of harsher judgement. As the perceived best player in the world, he had been expected to lead an average team to the title, as Maradona arguably did in 1986, but he had failed to replicate his performances at Barcelona with the national team, leading to the accusation that he cared less about his country than his club.[35]

Maradona was replaced by Sergio Batista, who had orchestrated Argentina's Olympic victory. Batista publicly stated that he intended to build the team around Messi, employing him as a false nine within a 4–3–3 system, as used to much success by Barcelona.[35][36] Although Messi scored a record 53 goals during the 2010–11 club season, he had not scored for Argentina in an official match since March 2009.[37][9] Despite the tactical change, his goal drought continued during the 2011 Copa América, hosted by Argentina. Their first two matches, against Bolivia and Colombia, ended in draws. Media and fans noted that he did not combine well with striker Carlos Tevez, who enjoyed greater popularity among the Argentine public; Messi was consequently booed by his own team's supporters for the first time in his career. During the crucial next match, with Tevez on the bench, he gave a well-received performance, assisting two goals in their 3–0 victory over Costa Rica. After the quarter-final against Uruguay ended in a 1–1 draw following extra time, with Messi having assisted their equaliser, Argentina were eliminated 4–5 in the penalty shootout by the eventual champions.[35]

2011–2013: assuming the captaincy[edit]

After Argentina's unsuccessful performance in the Copa América, Batista was replaced by Alejandro Sabella. Upon his appointment in August 2011, Sabella awarded the 24-year-old Messi the captaincy of the squad, in accord with then-captain Javier Mascherano. Reserved by nature, Messi went on to lead his squad by example as their best player, while Mascherano continued to fulfil the role of the team's on-field leader and motivator.[38][39] In a further redesign of the team, Sabella dismissed Tevez and brought in players with whom Messi had won the World Youth Championship and Olympic Games. Now playing in a free role in an improving team, Messi ended his goal drought by scoring during their first World Cup qualifying match against Chile on 7 October, his first official goal for Argentina in two-and-a-half years.[9][38]

Under Sabella, Messi's goalscoring rate drastically increased; where he had scored only 17 goals in 61 matches under his previous managers, he scored 25 times in 32 appearances during the following three years.[9][38] He netted a total of 12 goals in 9 games for Argentina in 2012, equalling the record held by Gabriel Batistuta for the most goals scored in a calendar year for their country.[40] His first international hat-trick came in a friendly against Switzerland on 29 February 2012, followed by two more hat-tricks over the next year-and-a-half in friendlies against Brazil and Guatemala. Messi then helped the team secure their place in the 2014 World Cup with a 5–2 victory over Paraguay on 10 September 2013 when he scored twice from penalty kicks, taking his international tally to 37 goals to become Argentina's second-highest goalscorer behind Batistuta. Overall, he had scored a total of 10 goals in 14 matches during the qualifying campaign.[9][41] Concurrently with his bettered performances, his relationship with his compatriots improved, as he gradually began to be perceived more favourably in Argentina.[38]

2014–2015: World Cup and Copa América finals[edit]

Ahead of the World Cup in Brazil, doubts persisted over Messi's form, as he finished an unsuccessful and injury-plagued season with Barcelona. At the start of the tournament, however, he gave strong performances, being elected man of the match in their first four matches.[42] In his first World Cup match as captain, he led them to a 2–1 victory over Bosnia and Herzegovina; he helped create Sead Kolašinac's own goal and scored their second strike after a dribble past three players, his first World Cup goal since his debut in the tournament eight years earlier.[43] During the second match against Iran, he scored an injury-time goal from 25 yards out to end the game in a 1–0 win, securing their qualification for the knockout phase.[44] He scored twice in the last group match, a 3–2 victory over Nigeria, his second goal coming from a free kick, as they finished first in their group.[45] Messi assisted a late goal in extra time to ensure a 1–0 win against Switzerland in the round of 16, and played in the 1–0 quarter-final win against Belgium as Argentina progressed to the semi-final of the World Cup for the first time since 1990.[46][47] Following a 0–0 draw in extra time, they eliminated the Netherlands 4–2 in a penalty shootout to reach the final, with Messi scoring his team's first penalty.[48]

Billed as Messi versus Germany, the world's best player against the best team, the final was a repeat of the 1990 final featuring Diego Maradona.[49] Within the first half-hour, Messi had started the play that led to a goal, but it was ruled offside. He missed several opportunities to open the scoring throughout the match, in particular at the start of the second half when his breakaway effort went wide of the far post. Substitute Mario Götze finally scored in the 113th minute, followed in the last minute of extra time by a free kick that Messi sent over the net, as Germany won the match 1–0 to claim the World Cup.[50] At the conclusion of the final, Messi was awarded the Golden Ball as the best player of the tournament. In addition to being the joint third-highest goalscorer, with four goals and an assist, he created the most chances, completed the most dribbling runs, made the most deliveries into the penalty area and produced the most throughballs in the competition.[42][51] However, his selection drew criticism due to his lack of goals in the knockout round; FIFA President Sepp Blatter expressed his surprise, while Maradona suggested that Messi had undeservedly been chosen for marketing purposes.[52]

Another final appearance, the third of Messi's senior international career, followed in the 2015 Copa América, held in Chile. Under the stewardship of former Barcelona manager Gerardo Martino, Argentina entered the tournament as title contenders due to their second-place achievement at the World Cup.[53][54] During the opening match against Paraguay, they were ahead two goals by half-time but lost their lead to end the match in a 2–2 draw; Messi had scored from a penalty kick, netting his only goal in the tournament.[55] Following a 1–0 win against defending champions Uruguay, Messi earned his 100th cap for his country in the final group match, a 1–0 win over Jamaica, becoming only the fifth Argentine to achieve this milestone.[56] In his 100 appearances, he had scored a total of 46 goals for Argentina, 22 of which came in official competitive matches.[9][56]

As Messi evolved from the team's symbolic captain into a genuine leader, he led Argentina to the knockout stage as group winners.[57] In the quarter-final, they created numerous chances, including a rebound header by Messi, but were repeatedly denied by Colombia's goalkeeper, and ultimately ended the match scoreless, leading to a 5–4 penalty shootout in their favour, with Messi netting his team's first spot kick.[58] At the semi-final stage, Messi excelled as a playmaker as he provided three assists and helped create three more goals in his side's 6–1 victory over Paraguay, receiving applause from the initially hostile crowd.[57] Argentina started the final as the odds-on title favourites, but were defeated by Chile 4–1 in a penalty shootout after a 0–0 extra-time draw. Faced with aggression from opposing players, including taking a boot to the midriff, Messi played below his standards, though he was the only Argentine to successfully convert his penalty.[59] At the close of the tournament, he was reportedly selected to receive the Most Valuable Player award but rejected the honour.[60] As Argentina continued a trophy drought that began in 1993, the World Cup and Copa América defeats again brought intense criticism for Messi from Argentine media and fans.[61]

2016–2017: third Copa América final, first retirement, and return[edit]

Messi's place in Argentina's Copa América Centenario squad was initially put in jeopardy when he sustained a back injury in a 1–0 friendly win over Honduras in a pre-Copa América warm-up match on 27 May 2016.[62] It was later reported that he had suffered a deep bruise in his lumbar region. He was later left on the bench in Argentina's 2–1 opening win over defending champions Chile on 6 June due to concerns regarding his fitness.[63] Although Messi was declared match-fit for his nation's second group match against Panama on 10 June, Martino left him on the bench once again; he replaced Augusto Fernández in the 61st minute and subsequently scored a hat-trick in 19 minutes, also starting the play which led to Sergio Agüero's goal, as the match ended in a 5–0 victory, sealing Argentina's place in the quarter-finals of the competition;[64] he was elected man of the match for his performance.[65]

"Did it annoy me that Messi took the record? A little, yes. You go around the world and people say, 'he's the top scorer for the Argentina national team.' But the advantage I have is that I'm second to an extraterrestrial."

– Gabriel Batistuta on the consolation of Messi breaking his record.[66]

On 18 June, in the quarter-final of the Copa América against Venezuela, Messi produced another man of the match performance,[67] assisting two goals and scoring another in a 4–1 victory, which enabled him to equal Gabriel Batistuta's national record of 54 goals in official international matches.[68] This record was broken three days later when Messi scored a free kick in a 4–0 semi-final win against hosts the United States; he also assisted two goals during the match as Argentina sealed a place in the final of the competition for a second consecutive year,[69] and was named man of the match once again.[70]

During a repeat of the previous year's final on 26 June, Argentina once again lost to Chile on penalties after a 0–0 deadlock, resulting in Messi's third consecutive defeat in a major tournament final with Argentina, and his fourth overall. After the match, Messi, who had missed his penalty in the shootout, announced his retirement from international football.[71] He stated, "I tried my hardest. The team has ended for me, a decision made."[72] Chile coach Juan Antonio Pizzi said after the match, "My generation can't compare him to Maradona that's for my generation, because of what Maradona did for Argentine football. But I think the best player ever played today here in the United States."[73] Messi finished the tournament as the second highest scorer, behind Eduardo Vargas, with five goals, and was the highest assist provider with four assists, also winning more Man of the Match awards than any other player in the tournament (3);[74] he was named to the team of the tournament for his performances, but missed out on the Golden Ball Award for best player, which went to Alexis Sánchez.[75]

Following his announcement, a campaign began in Argentina for Messi to change his mind about retiring.[76] He was greeted by fans with signs like "Don't go, Leo" when the team landed in Buenos Aires. President of Argentina Mauricio Macri urged Messi not to quit, stating, "We are lucky, it is one of life's pleasures, it is a gift from God to have the best player in the world in a footballing country like ours... Lionel Messi is the greatest thing we have in Argentina and we must take care of him."[77] Mayor of Buenos Aires Horacio Rodríguez Larreta unveiled a statue of Messi in the capital to convince him to reconsider retirement.[78] The campaign also continued in the streets and avenues of the Argentine capital, with about 50,000 supporters going to the Obelisco de Buenos Aires on 2 July, using the same slogan.[79]

"A lot of things went through my mind on the night of the final and I gave serious thought to quitting, but my love for my country and this shirt is too great."

– Messi reversing his decision from retiring on 12 August 2016[80]

Just a week after Messi announced his international retirement, Argentine newspaper La Nación reported that he was reconsidering playing for Argentina at the 2018 FIFA World Cup qualifiers in September.[81] On 12 August, it was confirmed that Messi had reversed his decision to retire from international football, and he was included in the squad for the national team's upcoming 2018 World Cup qualifiers.[82] On 1 September, in his first game back, he scored in a 1–0 home win over Uruguay in a 2018 World Cup qualifier.[83]

On 28 March 2017, Messi was suspended for four international games for insulting an assistant referee in a game against Chile on 23 March 2017. He was also fined CHF 10,000.[84][85] On 5 May, Messi's four match ban as well as his 10,000 CHF fine was lifted by FIFA after Argentina Football Association appealed against his suspension, which meant he could now play Argentina's remaining World Cup Qualifiers.[86] Argentina's place in the 2018 World Cup was in jeopardy going into their final qualifying match as they were sixth in their group, outside the five possible CONMEBOL World Cup qualifying spots, meaning they risked failing to qualify for the World Cup for the first time since 1970. On 10 October, Messi led his country to World Cup qualification in scoring a hat-trick as Argentina came from behind to defeat Ecuador 3–1 away; Argentina had not defeated Ecuador in Quito since 2001.[87] Messi's three goals saw him become the joint all-time leading scorer in CONMEBOL World Cup qualifiers with 21 goals, alongside Uruguay's Luis Suárez, overtaking the previous record which was held by compatriot Hernán Crespo.[87]

2018: World Cup[edit]

"The squad is the worst in their history. Even having the best player in the world was not capable of creating a competitive team. All the decline of recent times was hidden by this unrivalled genius [Messi]"

– Former Argentine player Osvaldo Ardiles on the decline in quality of Argentina being masked by Messi.[88]

Following on from their poor qualification campaign, expectations were not high going into the 2018 World Cup, with the team, without an injured Messi, losing 6–1 to Spain in March 2018.[89][90] Prior to Argentina's opener, there was speculation in the media over whether this would be Messi's final World Cup.[91] In the team's opening group match against Iceland on 16 June, Messi missed a potential match-winning penalty in an eventual 1–1 draw.[92] In Argentina's second game on 21 June, the team lost 3–0 to Croatia in a huge upset. Post-match the Argentina coach Jorge Sampaoli spoke of the lack of quality in the team surrounding Messi, saying "we quite simply couldn't pass to him to help him generate the situations he is used to. We worked to give him the ball but the opponent also worked hard to prevent him from getting the ball. We lost that battle".[93] Croatia captain and midfielder Luka Modrić also stated post match, "Messi is an incredible player but he can't do everything alone."[94]

In Argentina's final group match against Nigeria at the Krestovsky Stadium, Saint Petersburg on 26 June, Messi scored the opening goal in an eventual 2–1 victory, becoming the third Argentine after Diego Maradona and Gabriel Batistuta to score in three different World Cups; he also became the first player to score in the World Cup in his teens, twenties, and his thirties.[95] A goal of the tournament contender, Messi received a long pass from midfield and controlled the ball on the run with two touches before striking it across goal into the net with his weaker right foot.[96][97] He was awarded Man of the Match.[98] Argentina progressed to the second round as group runners-up behind Croatia.[99] In the round of 16 match against eventual champions France on 30 June, Messi set up Gabriel Mercado's and Sergio Agüero's goals in a 3–4 defeat, which saw Argentina eliminated from the World Cup.[100] With his two assists in his team's second round fixture, Messi became the first player to provide an assist in the last four World Cups, and also became the first player to provide two assists in a match for Argentina since Maradona had managed the same feat against South Korea in 1986.[101][102]

Following the tournament, Messi stated that he would not participate in Argentina's friendlies against Guatemala and Colombia in September, and commented that it would be unlikely that he would represent his nation for the remainder of the calendar year. Messi's absence from the national team and his continued failure to win a title with Argentina prompted speculation in the media that Messi might retire from international football once again.[103] In March 2019, however, he was called up to the Argentina squad once again for the team's friendlies against Venezuela and Morocco later that month.[104] A conversation with Lionel Scaloni and his idol Pablo Aimar made Messi reconsider his decision to retire.[105] He made his international return on 22 March, in a 3–1 friendly defeat to Venezuela, in Madrid.[106]

2019–2020: Copa América third-place and suspension[edit]

On 21 May, Messi was included in Scaloni's final 23-man squad for the 2019 Copa América.[107] In Argentina's second group match on 19 June, Messi scored the equalising goal from the penalty spot in a 1–1 draw against Paraguay.[108] After coming under criticism in the media over his performance following Argentina's 2–0 quarter-final victory over Venezuela on 28 June, Messi commented that it had not been his best Copa América, while also criticising the poor quality of the pitches.[109] Following Argentina's 2–0 semi-final defeat to hosts Brazil on 2 July, Messi was critical of the refereeing,[110][111] and alleged the competition was "set up" for Brazil to win.[112]

In the third-place match against Chile on 6 July, Messi set-up Agüero's opening goal from a free kick in an eventual 2–1 win, to help Argentina win the bronze medal; however, he was sent off along with Gary Medel in the 37th minute of play, after being involved in an altercation with the Chilean defender.[113] Following the match, Messi refused to collect his medal, and implied in a post-match interview that his comments following the semi-final led to his sending off.[114] Messi later issued an apology for his comments, but was fined $1,500 and was handed a one-match ban by CONMEBOL, which ruled him out of Argentina's next World Cup qualifier.[115] On 2 August, Messi was banned for three months from international football and was fined $50,000 by CONMEBOL for his comments against the referee's decisions; this ban meant he would miss Argentina's friendly matches against Chile, Mexico and Germany in September and October.[116] On 15 November, Messi played in the 2019 Superclásico de las Américas versus Brazil, scoring the winning goal by a rebound of his saved penalty.[117] On 8 October 2020, Messi scored a penalty in a 1–0 victory against Ecuador, giving Argentina a winning start to their 2022 World Cup qualifying campaign.[118]

2021–2022: Copa América and World Cup triumphs[edit]

"It was clear to me that I had to try until the last tournament and that I couldn't withdraw from the national team without winning something."

– Messi on winning the 2021 Copa América in an interview with Diario Sport.[119]

On 14 June 2021, Messi scored from a free kick in a 1–1 draw against Chile in Argentina's opening group match of the 2021 Copa América in Brazil.[120] On 21 June, Messi played in his 147th match as he equalled Javier Mascherano's record for most appearances for Argentina in a 1–0 win over Paraguay in their third game of the tournament.[121] A week later, he broke the record when he featured in a 4–1 win against Bolivia in his team's final group match, assisting Papu Gómez's opening goal and later scoring two.[122] On 3 July, Messi assisted twice and scored from a free-kick in a 3–0 win over Ecuador in the quarter-finals of the competition.[123] On 6 July, in a 1–1 draw in the semi-finals against Colombia, Messi made his 150th appearance for his country and registered his fifth assist of the tournament, a cut-back for Lautaro Martínez, matching his record of nine goal contributions in a single tournament from five years earlier; he later scored his spot kick in Argentina's eventual 3–2 penalty shoot-out victory to progress to his fifth international final.[124][125] On 10 July, Argentina defeated hosts and defending champions Brazil 1–0 in the final, giving Messi his first major international title and Argentina's first since 1993, as well as his nation's joint record 15th Copa América overall.[126][127] Messi was directly involved in nine out of the 12 goals scored by Argentina, scoring four and assisting five; he was named the player of the tournament for his performances, an honour he shared with Neymar. He also finished as top scorer with four goals tied with Colombia's Luis Díaz, with the Golden Boot awarded to Messi as he had more assists.[128][129]

On 9 September, Messi scored a hat-trick in a 3–0 home win over Bolivia in a 2022 World Cup qualifier which also moved him above Pelé as South America's top male international scorer with 79 goals.[130] In the 2022 Finalissima, the third edition of the CONMEBOL–UEFA Cup of Champions, at Wembley on 2 June 2022, Messi assisted twice in a 3–0 victory against Italy and was named player of the match, securing his second trophy for Argentina at the senior level.[131] Messi then followed this on 6 June with all five Argentina goals in a 5–0 victory in a friendly win over Estonia, overtaking Ferenc Puskás among the all-time international men's top scorers.[132]

At the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, Messi scored a penalty in Argentina's opening game, a 2–1 defeat to Saudi Arabia, before scoring with a low 20-yard strike in their next match against Mexico in which Argentina won 2–0, also recording an assist on Enzo Fernández's goal.[133] In the last 16 game against Australia, Messi scored the opening goal in Argentina's 2–1 win in what was his 1,000th senior career appearance,[134] and became the most-capped male South American (CONMEBOL member) footballer of all time, surpassing the previous record set by Ecuador's Iván Hurtado, as well as surpassing and equalling several other FIFA World Cup and national team records.[135][136] In the quarter-final against the Netherlands, Messi assisted Argentina's first goal for Nahuel Molina with a reverse pass and then scored a penalty as the game finished 2–2 after extra time. Argentina won 4–3 in the penalty shootout, with Messi scoring the first penalty.[137] In the semi-final against Croatia, Messi made a record-equalling 25th World Cup finals appearance, drawing level with Germany's Lothar Matthäus, and scored the opening goal with a penalty before he assisted Argentina's third goal scored by Julián Álvarez in a 3–0 win;[138] with his 11th World Cup goal, Messi overtook Batistuta to become Argentina's all-time top-scorer at the World Cup.[139] Argentina advanced to the final against France, with Messi stating that it would be his final World Cup appearance.[140][141]

In the 2022 FIFA World Cup final on 18 December, Messi made his record 26th World Cup match appearance at Lusail Stadium. He scored Argentina's opening goal with a penalty, becoming in the process the first player since the last-16 round was introduced in 1986 to score a goal in every round of a single World Cup edition.[142][143] After Argentina's eventual two-goal lead was erased by France forward Kylian Mbappé, who scored twice inside two minutes, Messi would score again in extra-time to restore Argentina's lead, before Mbappé again drew France level. Tied 3–3 after extra-time, the match went to a penalty shoot-out. Messi scored Argentina's first goal in the shoot-out, with Argentina eventually winning 4–2, ending the nation's 36-year wait for the trophy.[144] Messi received the Golden Ball for player of the tournament, becoming the first player to win it twice. He finished second in the Golden Boot race with seven goals in seven games, one behind Mbappé.[143] With his appearance and two goals in the final, Messi overtook Matthaüs as the player with most appearances at the World Cup (26), and Pelé as the player with most direct goal contributions at the World Cup (21 – 13 goals and 8 assists).[145] The championship game was widely acclaimed as one of the best of all time, with media coverage heavily framing it as a duel between Messi and Mbappé.[146][147][148][149] Following the game, Messi confirmed that he had no plans to retire from the national team, saying "I want to continue playing as a champion".[150]

2023–present: 100 international goals[edit]

In March 2023, Messi made his return to Argentina as a world champion with two appearances in friendlies in his home country. He scored his 99th international goal with a free-kick in Argentina's 2–0 win over Panama; this also marked his 800th senior career goal for club and country.[151] In the following match against Curaçao, Messi scored a hat-trick, his ninth for Argentina, and recorded an assist in a 7–0 win. The first of his three goals saw him reach 100 international goals, making Messi the third player in history to reach the milestone.[152]

Player profile[edit]

Style of play[edit]

Due to his short stature, Messi has a lower centre of gravity than taller players, which gives him greater agility, allowing him to change direction more quickly and evade opposing tackles;[153][154] this has led the Spanish media to dub him La Pulga Atómica ("The Atomic Flea").[155][156][157] Despite being physically unimposing, he possesses significant upper-body strength, which, combined with his low centre of gravity and resulting balance, aids him in withstanding physical challenges from opponents; he has consequently been noted for his lack of diving in a sport rife with playacting.[158][154][159] His short, strong legs allow him to excel in short bursts of acceleration while his quick feet enable him to retain control of the ball when dribbling at speed.[160] His former Barcelona manager Pep Guardiola once stated, "Messi is the only player that runs faster with the ball than he does without it."[161] Although he has improved his ability with his weaker foot since his mid-20s, Messi is predominantly a left-footed player; with the outside of his left foot, he usually begins dribbling runs, while he uses the inside of his foot to finish and provide passes and assists.[162][163]

A prolific goalscorer, Messi is known for his finishing, positioning, quick reactions, and ability to make attacking runs to beat the defensive line. He also functions in a playmaking role, courtesy of his vision and range of passing.[164] He has often been described as a magician; a conjurer, creating goals and opportunities where seemingly none exist.[165][166][167] Moreover, he is an accurate free kick and penalty kick taker.[154][168] As of September 2023, Messi ranks 5th all time in goals scored from direct free kicks with 65,[169] the most among active players.[170] He also has a penchant for scoring from chips.[171]

Messi's pace and technical ability enable him to undertake individual dribbling runs towards goal, in particular during counterattacks, usually starting from the halfway line or the right side of the pitch.[159][168][172] Widely considered to be the best dribbler in the world,[173] and one of the greatest dribblers of all time,[174] with regard to this ability, his former Argentina manager Diego Maradona has said of him, "The ball stays glued to his foot; I've seen great players in my career, but I've never seen anyone with Messi's ball control."[163] Beyond his individual qualities, he is also a well-rounded, hard-working team player, known for his creative combinations, in particular with former Barcelona midfielders Xavi and Andrés Iniesta.[153][154]

Tactically, Messi plays in a free attacking role; a versatile player, he is capable of attacking on either wing or through the centre of the pitch. His favoured position in childhood was the playmaker behind two strikers, known as the enganche in Argentine football, but he began his career in Spain as a left-winger or left-sided forward.[31] Upon his first-team debut, he was moved onto the right wing by manager Frank Rijkaard; from this position, he could more easily cut through the defence into the middle of the pitch and curl shots on goal with his left foot, rather than predominantly cross balls for teammates.[161] Under Guardiola and subsequent managers, he most often played in a false nine role; positioned as a centre-forward or lone striker, he would roam the centre, often moving deep into midfield and drawing defenders with him, in order to create and exploit spaces for passes, other teammates' attacking runs off the ball, Messi's own dribbling runs, or combinations with Xavi and Iniesta.[175] Under the stewardship of Luis Enrique, Messi initially returned to playing in the right-sided position that characterised much of his early career in the manager's 4–3–3 formation,[176][177] while he was increasingly deployed in a deeper, free playmaking role in later seasons.[178][179] Under manager Ernesto Valverde, Messi played in a variety of roles. While he occasionally continued to be deployed in a deeper role, from which he could make runs from behind into the box,[180] or even on the right wing[181] or as a false nine,[182][183] he was also used in a more offensive, central role in a 4–2–3–1,[179] or as a second striker in a 4–4–2 formation, where he was once again given the licence to drop deep, link-up with midfielders, orchestrate his team's attacking plays, and create chances for his attacking partner Suárez.[184][185]

As his career advanced, and his tendency to dribble diminished slightly with age, Messi began to dictate play in deeper areas of the pitch and developed into one of the best passers and playmakers in football history.[186][187][188] His work-rate off the ball and defensive responsibilities also decreased as his career progressed; by covering less ground on the pitch, and instead conserving his energy for short bursts of speed, he was able to improve his efficiency, movement, and positional play, and was also able to avoid muscular injuries, despite often playing a large number of matches throughout a particular season on a consistent basis. Indeed, while he was injury-prone in his early career, he was later able to improve his injury record by running less off the ball, and by adopting a stricter diet, training regime, and sleep schedule.[189] With the Argentina national team, Messi has similarly played anywhere along the frontline; under various managers, he has been employed on the right wing, as a false nine, as an out-and-out striker, in a supporting role alongside another forward, or in a deeper, free creative role as a classic number 10 playmaker or attacking midfielder behind the strikers.[36][190]

Reception and comparisons to Diego Maradona[edit]

"I have seen the player who will inherit my place in Argentinian football and his name is Messi."

– Diego Maradona hailing the 18-year-old Messi as his successor in February 2006[191]

A prodigious talent as a teenager, Messi established himself among the world's best players before age 20.[19] Diego Maradona considered the 18-year-old Messi the best player in the world alongside Ronaldinho, while the Brazilian himself, shortly after winning the Ballon d'Or, commented, "I'm not even the best at Barça", in reference to his protégé.[192][193] Four years later, after Messi had won his first Ballon d'Or by a record margin,[194] the public debate regarding his qualities as a player moved beyond his status in contemporary football to the possibility that he was one of the greatest players in history.[195][159][196] An early proponent was his then-manager Pep Guardiola, who, as early as August 2009, declared Messi to be the best player he had ever seen.[197] In the following years, this opinion gained greater acceptance among pundits, managers, former and current players,[198][199] and by the end of Barça's second treble-winning season, the view of Messi as one of the greatest footballers of all time had become the apparent view among many fans and pundits in continental Europe.[200][201] He initially received several dismissals by critics, based on the fact that he had not won an international trophy at senior level with Argentina,[202] until he won his first at the 2021 Copa América.[203]

Throughout his career, Messi has been compared with his late compatriot Diego Maradona, due to their similar playing styles as diminutive, left-footed dribblers. Initially, he was merely one of many young Argentine players, including his boyhood idol Pablo Aimar, to receive the "New Maradona" moniker, but as his career progressed, Messi proved his similarity beyond all previous contenders, establishing himself as the greatest player Argentina had produced since Maradona.[204][29] Jorge Valdano, who won the 1986 World Cup alongside Maradona, said in October 2013, "Messi is Maradona every day. For the last five years, Messi has been the Maradona of the World Cup in Mexico."[205] César Menotti, who as manager orchestrated their 1978 World Cup victory, echoed this sentiment when he opined that Messi plays "at the level of the best Maradona".[206] Other notable Argentines in the sport, such as Osvaldo Ardiles, Javier Zanetti, and Diego Simeone, have expressed their belief that Messi has overtaken Maradona as the best player in history.[207][208][209]

In Argentine society, prior to 2019, Messi was generally held in lesser esteem than Maradona, a consequence of not only his perceived uneven performances with the national team, but also of differences in class, personality, and background. Messi is in some ways the antithesis of his predecessor: where Maradona was an extroverted, controversial character who rose to greatness from the slums, Messi is reserved and unassuming, an unremarkable man outside of football.[1][210][211] An enduring mark against him is the fact that, through no fault of his own, he never proved himself in the Argentine Primera División as an upcoming player, achieving stardom overseas from a young age,[158][1] while his lack of outward passion for the Albiceleste shirt (until 2019 he did not sing the national anthem and is disinclined to emotional displays) have in the past led to the false perception that he felt Catalan rather than truly Argentine.[35] Football journalist Tim Vickery states the view among Argentines is that Messi "was always seen as more Catalan than one of them".[212] Despite having lived in Spain since age 13, Messi rejected the option of representing Spain internationally. He has said: "Argentina is my country, my family, my way of expressing myself. I would change all my records to make the people in my country happy."[213] Moreover, several pundits and footballing figures, including Maradona, questioned Messi's leadership with Argentina at times, despite his playing ability.[214][215][216] Vickery states the perception of Messi among Argentines changed in 2019, with Messi making a conscious effort to become "more one of the group, more Argentine", with Vickery adding that following the World Cup victory in 2022 Messi would now be held in the same esteem by his compatriots as Maradona.[212]

Comparisons with Cristiano Ronaldo[edit]

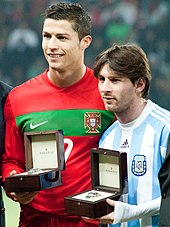

Among his contemporary peers, Messi is most often compared and contrasted with Portuguese forward Cristiano Ronaldo, as part of an ongoing rivalry that has been compared to past sports rivalries like the Muhammad Ali–Joe Frazier rivalry in boxing, the Roger Federer–Rafael Nadal rivalry in tennis, and the Prost–Senna rivalry from Formula One motor racing.[217][218]

Although Messi has at times denied any rivalry,[219][220] they are widely believed to push one another in their aim to be the best player in the world.[221] Since 2008, Messi has won eight Ballons d'Or to Ronaldo's five,[222] seven FIFA World's Best Player awards to Ronaldo's five, and six European Golden Shoes to Ronaldo's four.[223] Pundits and fans regularly argue the individual merits of both players.[221][224] Beyond their playing styles, the debate also revolves around their differing physiques – Ronaldo is 1.87 m (6 ft 1+1⁄2 in) with a muscular build – and contrasting public personalities with Ronaldo's self-confidence and theatrics a foil to Messi's humility.[225][226][227] From 2009–10 to 2017–18, Messi faced Ronaldo at least twice every season in El Clásico, which ranks among the world's most viewed annual sports events.[228] Off the pitch, Ronaldo is his direct competitor in terms of salary, sponsorships, and social media fanbase.[228]

After Messi led Argentina to victory in the 2022 FIFA World Cup, a number of football critics, commentators, and players have opined that Messi has settled the debate between the two players.[A]

In popular culture[edit]

According to France Football, Messi was the world's highest-paid footballer for five years out of six between 2009 and 2014; he was the first player to exceed the €40 million benchmark, with earnings of €41 million in 2013, and the €50–€60 million points, with income of €65 million in 2014.[232][233] Messi was second on Forbes list of the world's highest-paid athletes (after Cristiano Ronaldo) with income of $81.4 million from his salary and endorsements in 2015–16.[234] In 2018 he was the first player to exceed the €100m benchmark for a calendar year, with earnings of €126m ($154m) in combined income from salaries, bonuses and endorsements.[235] Forbes ranked him the world's highest-paid athlete in 2019.[236] From 2008, he was Barcelona's highest-paid player, receiving a salary that increased incrementally from €7.8 million to €13 million over the next five years.[237][238][239] Signing a new Barcelona contract in 2017, he earned $667,000 per week in wages, and Barcelona also paid him $59.6 million as a signing on bonus.[240] His buyout clause was set at $835 million (€700 million).[240] In 2020, Messi became the second footballer, as well as the second athlete in a team sport, after Cristiano Ronaldo, to surpass $1 billion in earnings during their careers.[241]

In addition to his salary and bonuses, much of his income derives from endorsements; SportsPro has consequently cited him as one of the world's most marketable athletes every year since their research began in 2010.[243] His main sponsor since 2006 is the sportswear company Adidas. As Barcelona's leading youth prospect, he had been signed with Nike since age 14, but transferred to Adidas after they successfully challenged their rival's claim to his image rights in court.[244] Over time, Messi established himself as their leading brand endorser;[228] from 2008, he had a long-running signature collection of Adidas F50 boots, and in 2015, he became the first footballer to receive his own sub-brand of Adidas boots, the Adidas Messi.[245][246] Since 2017, he has worn the latest version of the Adidas Nemeziz.[247] In 2015, a Barcelona jersey with Messi's name and number was the best-selling replica jersey worldwide.[248] At the 2022 World Cup, Adidas were sold out of Messi's Argentina No.10 jersey worldwide.[242]

As a commercial entity, Messi's marketing brand has been based exclusively on his talents and achievements as a player, in contrast to arguably more glamorous players like Cristiano Ronaldo and David Beckham. At the start of his career, he thus mainly held sponsorship contracts with companies that employ sports-oriented marketing, such as Adidas, Pepsi, and Konami.[250][251] From 2010 onwards, concurrently with his increased achievements as a player, his marketing appeal widened, leading to long-term endorsement deals with luxury brands Dolce & Gabbana and Audemars Piguet.[250][252] Messi is also a global brand ambassador for Gillette, Turkish Airlines, Ooredoo, and Tata Motors, among other companies.[253][254][255][256] Additionally, Messi was the face of Konami's video game series Pro Evolution Soccer, appearing on the covers of PES 2009, PES 2010, PES 2011 and PES 2020. He subsequently signed with rival company EA Sports to become the face of their series FIFA and has since appeared on four consecutive covers from FIFA 13 to FIFA 16.[257][258]

Messi's global popularity and influence are well documented. He was among the Time 100, an annual list of the world's most influential people as published by Time, in 2011, 2012 and 2023.[259][260][261] His fanbase on the social media website Facebook is among the largest of all public figures: within seven hours of its launch in April 2011, Messi's Facebook page had nearly seven million followers, and by July 2023 he had over 114 million followers, the second highest for a sportsperson after Cristiano Ronaldo.[262][263] He also has over 450 million Instagram followers, the second highest for an individual and sportsperson after Cristiano Ronaldo.[264] His World Cup celebration post from 18 December 2022 is the most liked post on Instagram with over 70 million likes.[265] According to a 2014 survey by sports research firm Repucom in 15 international markets, Messi was familiar to 87% of respondents around the world, of whom 78% perceived him favourably, making him the second-most recognised player globally, behind Ronaldo, and the most likable of all contemporary players.[266][267] On Messi's economic impact on the city in which he plays, Terry Gibson called him a "tourist attraction".[268]

Other events have illustrated Messi's presence in popular culture. Madame Tussauds unveiled their first wax sculpture of Messi at Wembley Stadium in 2012.[269] A gold replica of his left foot, weighing 25 kg (55 lb) and valued at $5.25 million, went on sale in Japan in March 2013 to raise funds for victims of the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami.[270] In 2013, a Turkish Airlines advertisement starring Messi, in which he engages in a selfie competition with then-Los Angeles Lakers star Kobe Bryant, was the most-watched ad on YouTube in the year of its release, receiving 137 million views, and was subsequently voted the best advertisement of the 2005–15 decade to commemorate YouTube's founding.[271][272] World Press Photo selected "The Final Game", a photograph of Messi facing the World Cup trophy after Argentina's final defeat to Germany, as the best sports image of 2014.[273] Messi, a documentary about his life by filmmaker Álex de la Iglesia, premiered at the Venice Film Festival in August 2014.[274]

In June 2021, Messi signed a five-year deal to become an ambassador for the Hard Rock Cafe brand. He stated, "sports and music are an integral part of my life. It is an honor to be the first athlete to partner with a brand who has a history of teaming with music legends."[275] In May 2022, Messi was unveiled as Saudi Arabia's tourism ambassador. Due to Saudi Arabia's poor human rights record, Messi was condemned for taking on the role which was viewed as an attempt of Saudi sportswashing.[276][277] In April 2023, Messi was featured in the 200 year old Thrissur Pooram festival in Kerala, India.[278] During Thrissur Pooram, which is one of the largest festivals in Asia, umbrellas carrying the illuminated cut outs of Messi holding the World Cup trophy were displayed on the top of caparisoned elephants during the Kudamattam ceremony.[279]

Personal life[edit]

Family and relationships[edit]

Since 2008, Messi has been in a relationship with Antonela Roccuzzo, a fellow native of Rosario.[280] He has known Roccuzzo since he was five years old, as she is the cousin of his childhood best friend, Lucas Scaglia, who is also a football player.[281] After keeping their relationship private for a year, Messi first confirmed their romance in an interview in January 2009, before going public a month later during a carnival in Sitges after the Barcelona–Espanyol derby.[282]

"Leo is not shy. He's introverted. He's reserved."

— Endocrinologist Diego Schwarzstein,[note 1] who addressed Messi's growth hormone deficiency from 1997 to 2001.

Messi and Roccuzzo have three sons. To celebrate his partner's first pregnancy, Messi placed the ball under his shirt after scoring in Argentina's 4–0 win against Ecuador on 2 June 2012, before confirming the pregnancy in an interview two weeks later.[284] Thiago was born in Barcelona on 2 November 2012.[285] In April 2015, Messi confirmed that they were expecting another child.[286] On 30 June 2017, he married Roccuzzo at a luxury hotel named Hotel City Center in Rosario.[287] In October 2017, his wife announced they were expecting their third child.[288] Messi and his family are Catholic Christians.[289]

Messi enjoys a close relationship with his immediate family members, particularly his mother, Celia, whose face he has tattooed on his left shoulder. His professional affairs are largely run as a family business: his father, Jorge, has been his agent since he was 14, and his oldest brother, Rodrigo, handles his daily schedule and publicity. His mother and other brother, Matías, manage his charitable organization, the Leo Messi Foundation, and take care of personal and professional matters in Rosario.[290]

Since leaving for Spain aged 13, Messi has maintained close ties to his hometown of Rosario, even preserving his distinct Rosarino accent. He has kept ownership of his family's old house, although it has long stood empty; he maintains a penthouse apartment in an exclusive residential building for his mother, as well as a family compound just outside the city. Once when he was in training with the national team in Buenos Aires, he made a three-hour trip by car to Rosario immediately after practice to have dinner with his family, spent the night with them, and returned to Buenos Aires the next day in time for practice. Messi keeps in daily contact via phone and text with a small group of confidants in Rosario, most of whom were fellow members of "The Machine of '87" at Newell's Old Boys. While at Barcelona he lived in Castelldefels, a village near Barcelona. He was on bad terms with the club after his transfer to Barcelona, but by 2012 their public feud had ended, with Newell's embracing their ties with Messi, even issuing a club membership card to his newborn son.[158][291][292] Messi has long planned to return to Rosario to end his playing career at Newell's.[293] Messi holds triple citizenship, as he is a citizen of Argentina, Italy, and Spain.[294] His favourite meals include asado (traditional South American barbecue), milanesa and pasta, and he prefers his mate unsweetened.[295]

Philanthropy[edit]

Throughout his career, Messi has been involved in charitable efforts aimed at vulnerable children, a commitment that stems in part from the medical difficulties he faced in his own childhood. Since 2004, he has contributed his time and finances to the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), an organisation with which Barcelona also have a strong association.[296][297] Messi has served as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador since his appointment in March 2010, completing his first field mission for the organisation four months later as he travelled to Haiti to bring public awareness to the plight of the country's children in the wake of the recent earthquake. He has since participated in UNICEF campaigns targeting HIV prevention, education, and the social inclusion of disabled children.[298] To celebrate his son's first birthday, in November 2013, Messi and Thiago were part of a publicity campaign to raise awareness of mortality rates among disadvantaged children.[299]

In addition to his work with UNICEF, Messi founded his own charitable organisation, the Leo Messi Foundation, which supports access to health care, education, and sport for children.[300] It was established in 2007 following a visit Messi paid to a hospital for terminally ill children in Boston, an experience that resonated with him to the point that he decided to reinvest part of his earnings into society.[291] Through his foundation, Messi has awarded research grants, financed medical training, and invested in the development of medical centres and projects in Argentina, Spain, and elsewhere in the world.[291][301] In addition to his own fundraising activities, such as his global "Messi and Friends" football matches, his foundation receives financial support from various companies to which he has assigned his name in endorsement agreements, with Adidas as their main sponsor.[302][303]

Messi has also invested in youth football in Argentina: he financially supports Sarmiento, a football club based in the Rosario neighbourhood where he was born, committing in 2013 to the refurbishment of their facilities and the installation of all-weather pitches, and funds the management of several youth players at Newell's Old Boys and rival club Rosario Central, as well as at River Plate and Boca Juniors in Buenos Aires.[291] At Newell's Old Boys, his boyhood club, he funded the 2012 construction of a new gymnasium and a dormitory inside the club's stadium for their youth academy. His former youth coach at Newell's, Ernesto Vecchio, is employed by the Leo Messi Foundation as a talent scout for young players.[158] On 7 June 2016, Messi won a libel case against La Razón newspaper and was awarded €65,000 in damages, which he donated to the charity Médecins Sans Frontières.[304] Messi made a donation worth €1 million ($1.1 million) to fight the spread of coronavirus.[305] This was split between Clinic Barcelona hospital in Barcelona, Spain and his native Argentina.[306] In addition to this, Messi along with his fellow FC Barcelona teammates announced he will be taking a 70% cut in salaries during the 2020 coronavirus emergency, and contribute further to the club to provide fully to salaries of all the clubs employees.[307]

In November 2016, with the Argentine Football Association being run by a FIFA committee for emergency due to an economic crisis, it was reported that three of the national team's security staff told Messi that they had not received their salaries for six months. He stepped in and paid the salaries of the three members.[308][309] In February 2021, Messi donated to the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya his Adidas shoes which he wore when he scored his 644th goal for Barcelona and broke Pelé's record for most goals scored for a single club; the shoes were later auctioned off in April by the museum for charity to help children with cancer and were sold for £125,000.[310]

In advance of the 2021 Copa América in Uruguay, Messi donated three signed shirts to the Chinese pharmaceutical firm Sinovac Biotech—whose directors spoke of their admiration for Messi—in order to secure 50,000 doses of Sinovac's COVID-19 vaccine, CoronaVac, in the hope of vaccinating all of South America's football players.[311] A deal brokered by Uruguay's president Luis Lacalle Pou, the plan to prioritise football players caused some controversy given widespread vaccine scarcity in the region, with the Mayor of Canelones Yamandú Orsi remarking that "Just as the president manifested cooperation with CONMEBOL to vaccinate for the Copa América, he could just as well have the same consideration for Canelones".[311]

Tax fraud[edit]

Messi's financial affairs came under investigation in 2013 for suspected tax evasion. Offshore companies in tax havens Uruguay and Belize were used to evade €4.1 million in taxes related to sponsorship earnings between 2007 and 2009. An unrelated shell company in Panama set up in 2012 was subsequently identified as belonging to the Messis in the Panama Papers data leak. Messi, who pleaded ignorance of the alleged scheme, voluntarily paid arrears of €5.1 million in August 2013. On 6 July 2016, Messi and his father were both found guilty of tax fraud and were handed suspended 21-month prison sentences and respectively ordered to pay €1.7 million and €1.4 million in fines.[312] Facing the judge, he said, "I just played football. I signed the contracts because I trusted my dad and the lawyers and we had decided that they would take charge of those things."[313]

Career statistics[edit]

Club[edit]

- As of match played 21 October 2023

| Club | Season | League | National cup[a] | Continental[b] | Other | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Barcelona C | 2003–04[314] | Tercera División | 10 | 5 | — | — | — | 10 | 5 | |||

| Barcelona B | 2003–04[315] | Segunda División B | 5 | 0 | — | — | — | 5 | 0 | |||

| 2004–05[316] | Segunda División B | 17 | 6 | — | — | — | 17 | 6 | ||||

| Total | 22 | 6 | — | — | — | 22 | 6 | |||||

| Barcelona | 2004–05[316] | La Liga | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | — | 9 | 1 | |

| 2005–06[317] | La Liga | 17 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 8 | |

| 2006–07[318] | La Liga | 26 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3[c] | 0 | 36 | 17 | |

| 2007–08[319] | La Liga | 28 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 9 | 6 | — | 40 | 16 | ||

| 2008–09[320] | La Liga | 31 | 23 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 9 | — | 51 | 38 | ||

| 2009–10[321] | La Liga | 35 | 34 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 8 | 4[d] | 4 | 53 | 47 | |

| 2010–11[37] | La Liga | 33 | 31 | 7 | 7 | 13 | 12 | 2[e] | 3 | 55 | 53 | |

| 2011–12[322] | La Liga | 37 | 50 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 14 | 5[f] | 6 | 60 | 73 | |

| 2012–13[323] | La Liga | 32 | 46 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 2[e] | 2 | 50 | 60 | |

| 2013–14[324] | La Liga | 31 | 28 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 2[e] | 0 | 46 | 41 | |

| 2014–15[325] | La Liga | 38 | 43 | 6 | 5 | 13 | 10 | — | 57 | 58 | ||

| 2015–16[326] | La Liga | 33 | 26 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4[g] | 4 | 49 | 41 | |

| 2016–17[327] | La Liga | 34 | 37 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 2[e] | 1 | 52 | 54 | |

| 2017–18[328] | La Liga | 36 | 34 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 2[e] | 1 | 54 | 45 | |

| 2018–19[329] | La Liga | 34 | 36 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 12 | 1[e] | 0 | 50 | 51 | |

| 2019–20[330] | La Liga | 33 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1[e] | 1 | 44 | 31 | |

| 2020–21[331] | La Liga | 35 | 30 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 1[e] | 0 | 47 | 38 | |

| Total | 520 | 474 | 80 | 56 | 149 | 120 | 29 | 22 | 778 | 672 | ||

| Paris Saint-Germain | 2021–22[332] | Ligue 1 | 26 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 5 | — | 34 | 11 | |

| 2022–23[333] | Ligue 1 | 32 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 1[h] | 1 | 41 | 21 | |

| Total | 58 | 22 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 75 | 32 | ||

| Inter Miami | 2023 | MLS | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | — | 7[i] | 10 | 14 | 11 | |

| Career total | 615 | 508 | 83 | 56 | 163 | 129 | 37 | 33 | 899 | 726 | ||

- ^ Includes Copa del Rey, Coupe de France, U.S. Open Cup

- ^ Includes UEFA Champions League

- ^ One appearance in UEFA Super Cup, two appearances in Supercopa de España

- ^ One appearance in UEFA Super Cup, one appearance and two goals in Supercopa de España, two appearances and two goals in FIFA Club World Cup

- ^ a b c d e f g h Appearance(s) in Supercopa de España

- ^ One appearance and one goal in UEFA Super Cup, two appearances and three goals in Supercopa de España, two appearances and two goals in FIFA Club World Cup

- ^ One appearance and two goals in UEFA Super Cup, two appearances and one goal in Supercopa de España, one appearance and one goal in FIFA Club World Cup

- ^ Appearance in Trophée des Champions

- ^ Appearance(s) in Leagues Cup

International[edit]

- As of match played 22 November 2023

| Team | Year | Competitive | Friendly | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Argentina U20[2][3] | 2004 | — | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| 2005 | 16[a] | 11 | — | 16 | 11 | ||

| Total | 16 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 18 | 14 | |

| Argentina U23[27] | 2008 | 5[b] | 2 | — | 5[α] | 2 | |

| Total | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | |

| Argentina[9][337] | 2005 | 3[c] | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| 2006 | 3[d] | 1 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| 2007 | 10[e] | 4 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 6 | |

| 2008 | 6[c] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | |

| 2009 | 8[c] | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 3 | |

| 2010 | 5[d] | 0 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 2 | |

| 2011 | 8[f] | 2 | 5 | 2 | 13 | 4 | |

| 2012 | 5[c] | 5 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 12 | |

| 2013 | 5[c] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | |

| 2014 | 7[d] | 4 | 7 | 4 | 14 | 8 | |

| 2015 | 6[g] | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 4 | |

| 2016 | 10[h] | 8 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 8 | |

| 2017 | 5[c] | 4 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 4 | |

| 2018 | 4[d] | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| 2019 | 6[g] | 1 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 5 | |

| 2020 | 4[c] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| 2021 | 16[i] | 9 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 9 | |

| 2022 | 10[j] | 8 | 4 | 10 | 14 | 18 | |

| 2023 | 5[c] | 3 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 8 | |

| Total | 126 | 57 | 54 | 49 | 180 | 106 | |

| Career total | 147 | 70 | 56 | 52 | 203 | 122 | |

- ^ Nine appearances and five goals in the 2005 South American U-20 Championship, seven appearances and six goals in the 2005 FIFA World Youth Championship

- ^ Appearances in Summer Olympics

- ^ a b c d e f g h Appearance(s) in FIFA World Cup qualification

- ^ a b c d Appearance(s) in FIFA World Cup

- ^ Six appearances and two goals in Copa América, four appearances and two goals in FIFA World Cup qualification

- ^ Four appearances in Copa América, four appearances and two goals in FIFA World Cup qualification

- ^ a b Appearance(s) in Copa América

- ^ Five appearances and three goals in FIFA World Cup qualification, five appearances and five goals in Copa América

- ^ Nine appearances and five goals in FIFA World Cup qualification, seven appearances and four goals in Copa América

- ^ Two appearances and one goal in FIFA World Cup qualification, one appearance in CONMEBOL–UEFA Cup of Champions, seven appearances and seven goals in FIFA World Cup

Honours[edit]

Barcelona[338]

- La Liga: 2004–05, 2005–06, 2008–09, 2009–10, 2010–11, 2012–13, 2014–15, 2015–16, 2017–18, 2018–19

- Copa del Rey: 2008–09, 2011–12, 2014–15, 2015–16, 2016–17, 2017–18, 2020–21

- Supercopa de España: 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016, 2018

- UEFA Champions League: 2005–06,[note 2] 2008–09, 2010–11, 2014–15

- UEFA Super Cup: 2009, 2011, 2015

- FIFA Club World Cup: 2009, 2011, 2015

Paris Saint-Germain[339]

Inter Miami

Argentina U20

Argentina U23

Argentina

Individual

- Ballon d'Or/FIFA Ballon d'Or: 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2019, 2021, 2023[341][342]

- FIFA World Player of the Year: 2009[341]

- The Best FIFA Men's Player: 2019,[341] 2022[343]

- European Golden Shoe: 2009–10, 2011–12, 2012–13, 2016–17, 2017–18, 2018–19[341]

- FIFA World Cup Golden Ball: 2014, 2022[341]

- FIFA World Cup Silver Boot: 2022

- FIFA Club World Cup Golden Ball: 2009, 2011

- FIFA U-20 World Cup Golden Ball: 2005

- FIFA U-20 World Cup Golden Boot: 2005

- UEFA Men's Player of the Year Award: 2008–09, 2010–11, 2014–15

- UEFA Champions League top scorer: 2008–09, 2009–10, 2010–11, 2011–12, 2014–15, 2018–19

- Copa América Best Player: 2015, 2021

- Copa América Top Goalscorer: 2021

- La Liga Best Player: 2008–09, 2009–10, 2010–11, 2011–12, 2012–13, 2014–15[344][345][346]

- Pichichi Trophy: 2009−10, 2011–12, 2012−13, 2016–17, 2017−18, 2018–19, 2019–20, 2020–21

- Laureus World Sportsman of the Year: 2020,[341] 2023[347]

- Argentine Footballer of the Year: 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022[344][341]

See also[edit]

- European Cup and UEFA Champions League records and statistics

- La Liga records and statistics

- List of FC Barcelona players

- List of FC Barcelona records and statistics

- List of FIFA World Cup winning players

- List of largest sports contracts

- List of men's footballers with 50 or more international goals

- List of men's footballers with 100 or more international caps

- List of men's footballers with 500 or more goals

- List of men's footballers with the most official appearances

- List of most-followed Instagram accounts

- List of most-liked Instagram posts

- List of top international men's football goalscorers by country

- List of players who have appeared in multiple FIFA World Cups

- List of association football rivalries

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Himmelman, Jeff (5 June 2014). "The Burden of Being Messi". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ a b Balagué 2013, pp. 209–219.

- ^ a b Balagué 2013, pp. 220–240.

- ^ a b c "Magic Messi Sparks High Drama in the Lowlands". FIFA. July 2005. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (22 August 2005). "Messi Handles 'New Maradona' Tag". BBC Sport. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Messi's Debut Dream Turns Sour". ESPN FC. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Messi Tries Again as Argentina Face Paraguay". ESPN FC. 2 September 2005. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011.

- ^ "Messi Is a Jewel Says Argentina Coach". ESPN FC. 10 October 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mamrud, Roberto. "Lionel Andrés Messi – Century of International Appearances". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Vickery, Tim (5 June 2006). "Messi Comes of Age". BBC Sport. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Argentina 6–0 Serbia & Montenegro". BBC Sport. 16 June 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Holland 0–0 Argentina". BBC Sport. 21 June 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Lisi 2011, pp. 470–471.

- ^ "Argentina 2–1 Mexico (aet)". BBC Sport. 24 June 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Lisi 2011, pp. 485–486.

- ^ Lisi 2011, pp. 492–493.

- ^ Balagué 2013, pp. 382–383.

- ^ "Argentines Wonder Why Messi Sat Out". The New York Times. 2 July 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

NotBestwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Balagué 2013, pp. 384–387.

- ^ "Argentina into Last Eight of Copa". BBC Sport. 3 July 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Tevez Nets in Argentina Victory". BBC Sport. 29 June 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "Missing Some Stars, Brazil Wins Copa América". The New York Times. 16 July 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Caioli 2012, p. 156.

- ^ Homewood, Brian (6 August 2008). "Court Blocks Messi from Olympics Soccer". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Hunter 2012, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Balagué 2013, pp. 436–437.

- ^ a b "Report and Statistics: Men's and Women's Olympic Football Tournaments Beijing 2008" (PDF). FIFA. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Lisi 2011, pp. 533–539.

- ^ Chadband, Ian (28 April 2009). "Lionel Messi Can Achieve More at Barcelona than Diego Maradona". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Balagué 2013, pp. 155–156, 405–406.

- ^ Smith, Rory (22 June 2010). "Greece 0 Argentina 2: Match Report". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Lisi 2011, pp. 564–567.

- ^ "Adidas Golden Ball Nominees Announced". FIFA. 9 July 2010. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d Balagué 2013, pp. 414–420.

- ^ a b Cox, Michael (13 November 2014). "Lionel Messi Showing Some Promising Signs in a New Argentina Role". ESPN FC. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Matches 2010–11was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d Balagué 2013, pp. 595–602.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (10 July 2014). "If Messi Is Argentina's Star, Then Mascherano Is the Glue". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Adamson, Mike (10 December 2012). "Lionel Messi's Incredible Record-Breaking Year in Numbers". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "FIFA World Cup Qualifying: Paraguay 2 Argentina 5". FourFourTwo. 11 September 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b "2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil Technical Report and Statistics" (PDF). FIFA. pp. 170–171. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Sanghera, Mandeep (15 June 2014). "Argentina 2–1 Bos-Herce". BBC Sport. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Smyth, Rob (21 June 2014). "Argentina v Iran, World Cup 2014: Live". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Chowdhury, Saj (25 June 2014). "Nigeria 2–3 Argentina". BBC Sport. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Jurejko, Jonathan (1 July 2014). "Argentina 1–0 Switzerland". BBC Sport. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Ferris, Ken (5 July 2014). "Argentina Beat Belgium to Reach First Semi since 1990". Reuters. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ McNulty, Phil (9 July 2014). "Netherlands 0–0 Argentina". BBC Sport. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Futterman, Matthew (11 July 2014). "The World Cup Final: The Best Team vs. the Best Player". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Murray, Scott (13 July 2014). "World Cup Final 2014: Germany v Argentina – as It Happened". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Bate, Adam (16 July 2014). "World Cup Final: Was Lionel Messi Really a Disappointment in Brazil or Have We Just Become Numb to His Genius?". Sky Sports. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "World Cup 2014: Lionel Messi Golden Ball Surprised Sepp Blatter". BBC Sport. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Gerardo 'Tata' Martino Appointed Argentina Coach". CNN. 13 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Gowar, Rex; Torres, Santiago; Palmer, Justin (29 June 2015). "Messi Bemoans Scoring Difficulties at Copa América". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Argentina 2–2 Paraguay". BBC Sport. 13 June 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b Long, Gideon; Jimenez, Tony (21 June 2015). "Messi Wins 100th Argentina Cap". Reuters. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b Wilson, Jonathan (1 July 2015). "Even Hostile Chile Fans Forced to Acknowledge Lionel Messi's Greatness". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Argentina Beat Colombia on Penalties to Reach Copa America Semifinal". ESPN FC. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (5 July 2015). "Hosts Chile Stun Argentina to Claim First Copa América Title on Penalties". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Garcia, Adriana (7 July 2015). "Argentina's Lionel Messi Grateful for Support after Copa América Defeat". ESPN FC. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Ferris, Ken (5 August 2015). "Coach: I'd Have Stopped Playing for Argentina if I Was Messi". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 February 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Lionel Messi leaves Argentina's friendly win vs. Honduras with back injury". ESPN FC. 27 May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Argentina top Chile in rematch of last year's Copa América final". The Guardian. 7 June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Lionel Messi scores brilliant hat-trick as Argentina surge into quarter-finals". The Guardian. 11 June 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Match 16 : Argentina vs Panama". Copa América Centenario. 10 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Garcia, Adriana (13 November 2017). "Gabriel Batistuta – Lionel Messi taking my Argentina record annoyed me". ESPN. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ "Match 27 : Argentina vs Venezuela". Copa América Centenario. 18 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Copa America: Lionel Messi equals Gabriel Batistuta's Argentina record". BBC Sport. 19 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ "Lionel Messi equals Argentina's all-time goal-scoring record". ESPN FC. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Match 29 : United States vs Argentina". Copa América Centenario. 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ "Lionel Messi retires from Argentina after Copa America final loss to Chile". ESPN FC. 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Devastated Messi announces likely retirement from Argentina". CNN. 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Lionel Messi says his Argentina career is over after Copa América final defeat". The Guardian. 26 June 2016.

- ^ "HTML Center". estadisticas.conmebol.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ "Copa América 2016: Awards". Copa America Organisation. 27 June 2016. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Argentina don't want Messi to retire". Sky Sports. 28 June 2016.