Propaganda kimono

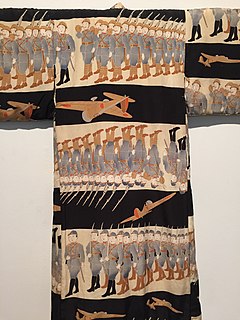

Kimono that carried designs depicting scenes from contemporary life became popular in the Empire of Japan between 1900 and 1945, during Japan's involvement in WWII. Now referred to as omoshirogara (面白柄, lit. "interesting" or "novelty" designs),[1] the decoration of many kimono produced during this time often depicted the military and political actions of Japan during its involvement in the war on the side of the Axis powers. In English, these kimono are commonly referred to as 'propaganda kimono'.[2][3] Traditional items of clothing that were not kimono, such as nagajuban (underkimono), haori (jackets worn over kimono) and haura (the decorative inner linings of men's haori) also featured wartime omoshirogara, as did miyamari, the kimono worn by infants when taken to a Shinto shrine to be blessed. Omoshirogara garments were typically worn inside the home or at private parties, during which the host would show them off to small groups of family or friends,[4] and were worn by men, women and children.

History[edit]

Among the factors that led to the emergence of propaganda kimono, three stand out: the introduction of modern textile manufacturing and printing equipment into Japan in the late 19th century,[5] the social and political impetus for Japan to modernize,[6] and, following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, political desire to rally support for colonial expansion.[3] The introduction of Western textile manufacturing techniques and machinery allowed textile manufacturers to produce printed fabric at a quicker and cheaper rate than traditional dye techniques allowed, and later support from the Japanese population for colonialist expansion would lead into support in WWII against the Allied powers.[3]

Much of the imagery used on propaganda kimono was widely used on other media and consumer goods, such as popular magazines, toys, posters and dolls.[7][8] Some typical omoshirogara designs from the early 1920s to the mid-1930s focused on the outward signs of modernity, depicting a sleek, Westernized, consumerist future – cityscapes with subways and skyscrapers, ocean liners, steaming locomotives, sleek cars and airplanes. Other designs showed images reflecting current events (e.g., the visit of the Graf Zeppelin in 1929)[9] and social trends, such as depictions of the "modern girl", whose new pastimes were cocktails, nightclubs, and jazz music.[10] Regardless of the subject matter, wartime omoshirogara employed a bold colour palette, showing direct influences from Art Deco, Dadaism and Cubism, as well as social realism and other graphic media.[8][11]

By the later 1920s, and particularly following the crash of 1929, with Japan's economically disastrous return to the gold standard, conservative and ultra-nationalist forces in the military and government began to push back against the modernist trends in Japanese society, and sought to reassert more traditional values.[12] Military power, the will to use it, and the ability to manufacture its hardware became central to Japan's self-image. As a result, the propaganda kimono designs took on an increasing militaristic air.[7]

Only since the late 20th-century have scholars in Japan, Europe and the United States begun to seriously study Japanese propaganda kimono.[13] In 2005, The Bard Graduate Center mounted one of the first major exhibits[14] of these kimono, curated by Jacqueline M. Atkins, an American textile historian and recognized scholar of Japanese 20th century textiles. The exhibition also was shown at the Allentown Art Museum and the Honolulu Academy of Art (2006–2007).[14] The Metropolitan Museum of Art,[15] The Johann Jacobs Museum[16] (Zurich), the Edward Thorp Gallery[17] in New York City, and the Saint Louis Art Museum[18] have mounted exhibits that have included propaganda kimono. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts received a significant donation of wartime and other omoshirogara kimono from an American collector in 2010.[19]

Gallery[edit]

- Propaganda kimono from the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Man's under-kimono (nagajuban) with scene of the Russo-Japanese War

-

Man's under-kimono (nagajuban) with "Italy in Ethiopia" symbols

-

Woman's kimono with planes and hinomaru flags

-

Kimono celebrating the role of animals in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria

-

Boy's wool kimono, c. 1933, showing Japanese military action in China. Norakuro, the faithful dog, was a traditional character.

-

Boy's propaganda kimono c. 1940, showing symbols of the Axis powers

References[edit]

- ^ Atkins, Jacqueline M. (September 2008). "Omoshirogara Textile Design and Children's Clothing in Japan 1910-1930". Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. Paper 77. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Wakakuwa, Midori (2005). "War-Promoting Kimono (1931-45)". In Atkins, Jacqueline (ed.). Wearing propaganda: Textiles on the home front in Japan, Britain, and the United States, 1931-1945. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press in association with the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture. pp. 183–204. ISBN 978-0300109252.

- ^ a b c Dower, John W.; Morse, Anne Nishimura; Atkins, Jacqueline M.; Sharf, Frederic A. (2012). The brittle decade: Visualizing Japan in the 1930s (1st ed.). Boston: MFA Publications. ISBN 978-0878467693.

- ^ Kashiwagi, Hiroshi (2005). "Design and War: Kimono as 'Parlor-Performance' Propaganda". In Atkins, Jacqueline M. (ed.). Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press. pp. 171–182. ISBN 978-0300109252.

- ^ Deacon, Deborah A.; Calvin, Paula E. (2014). War Imagery in Women's Textiles : A worldwide study of weaving, knitting, sewing, quilting, rug making and other fabric arts. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 130. ISBN 978-0786474660.

- ^ Brown, Kendall H.; et al. (2002). "Flowers of Taisho Images of Women in Japanese Society and Art, 1915-1933". Taishō chic: Japanese modernity, nostalgia and deco : [exhibition, Honolulu academy of arts, January 31 to March 15, 2002] (2. print. ed.). Honolulu: Honolulu academy of arts. pp. 17–22. ISBN 0-295-98244-6.

- ^ a b Dower, John W.; Morse, Anne Nishimura; Atkins, Jacqueline M.; Sharf, Frederic A. (2012). "Wearing Novelty". The Brittle Decade : visualizing Japan in the 1930s. MFA Publications. pp. 91–143.

- ^ a b Kaneko, Maki (2016). "War Heroes of Modern Japan: Early 1930s War Fever and the Three Brave Bombers". In Hu, Philip K.; et al. (eds.). Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan (1st ed.). Saint Louis Art Museum. pp. 69–82.

- ^ Grossman, Dan (August 15, 2010). "Graf Zeppelin's Round-the-World flight: August, 1929". airships.net. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

The ship landed to a tumultuous welcome and massive press coverage in Japan

- ^ Atkins, Jacqueline (2005). "'Extravagance is the Enemy': Fashion and textiles in wartime Japan". In Atkins, Jacqueline (ed.). Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press. pp. 156–170. ISBN 978-0300109252.

- ^ Atkins, Jacqueline (2005). "An Arsenal of Design: Themes, Motifs and Metaphors in Propaganda Textiles". In Atkins, Jacqueline (ed.). Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945 (1st ed.). New Haven, USA: Yale University Press. pp. 258–365. ISBN 978-0300109252.

- ^ Gordon, Andrew (2009). "The Depression Crisis and Responses". A modern history of Japan: from Tokugawa times to the present (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 181–195. ISBN 978-0-19-533922-2.

...this move brought disaster.

- ^ Atkins, Jacqueline (2005). "Introduction". In Atkins, Jacqueline (ed.). Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press. pp. 24–28. ISBN 978-0300109252.

- ^ a b "Bard Graduate Center Gallery Exhibitions – November 18, 2005 – February 12, 2006, 'Wearing Propaganda: Textiles on the Home Front in Japan, Britain, and the United States 1931–1945'". Bard Graduate Center. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07.

- ^ "Kimono: A Modern History". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "Omoshirogara". Johann Jacobs Museum. Archived from the original on 2018-01-17.

- ^ "Japanese Propaganda Kimonos". Edward Thorp Gallary. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06.

- ^ "Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan". Saint Louis Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2017-10-16.

- ^ Museum of Fine Arts Boston, online Artwork archive. "Fourteen (14) Japanese propaganda-print garments and one obi". mfa.org. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

Gift of Norman Brosterman, East Hampton, NY to the MFA. (Accession date: May 19, 2010)