Peridexion tree

The peridexion tree (from Greek δένδρον περιδέξιον, déndron peridéxion) or perindens is a mythological tree discussed in the Physiologus, an early Greek-language Christian didactic text and compendium, and popular in medieval bestiaries. It is described as growing in India, attracting doves and deterring serpents, making for a fable about Christian salvation.

Etymology[edit]

The name comes from the Greek δένδρον περιδέξιον (déndron peridéxion), peridéxion meaning ambidextrous, dextrous, or convenient.[1] Latin-language manuscripts, such as the Aberdeen Bestiary, refer to it as "perindens."[2]

Description[edit]

Physiologus describes the tree as growing in India and having a sweet fruit that doves enjoy eating. A serpent that seeks to eat the doves is afraid of the tree and its shadow, so it waits for the doves to stray from the protection of the tree in order to attack them.[3] This is a reminder to the text's Christian audience of salvation, where the tree represents Christian faith and the serpent is the devil waiting to take those who leave the church, drawing comparison with Judas Iscariot.[3] The fruits are described by the text as "heavenly wisdom" and the doves as the Holy Spirit.[4]

Origins[edit]

Physiologus provides the oldest attested description of the tree. The text was written in the 2nd or 3rd century AD by an anonymous Greek author who had access to Greek classics, the Bible, works by early Christian authors, and fables. It became a popular book and was translated into many languages, including Latin, and was widespread in Western Europe by the 9th century. No originals are known, but due to its popularity there are many later extant manuscripts that include the text.[5]

German philologist Otto Schönberger had suggested the tree may be sourced from Pliny the Elder's Natural History, which reports how the ash tree is a deterrent to snakes, combined with the biblical story of the Tree of Life.[6] Serpents and dragons guarding trees is a well-attested trope in Hellenistic literature and iconography. In Greek mythology, the dragon Ladon guarded the golden apples of the Hesperides, a story referenced by Ovid, Hesiod, and Apollonius of Rhodes, and Herodotus in his Histories referenced winged serpents guarding spice trees in Arabia.[7]

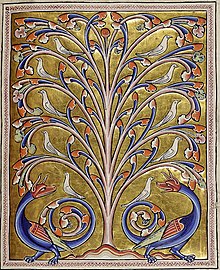

Depictions in art[edit]

The peridexion tree is depicted in illuminated manuscripts from the medieval period. One bestiary in which it is depicted is the Houghton Library, MS Typ 101 (cat. no. 28), kept in the Houghton Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[8] This manuscript was copied directly from an earlier one, the National Library of Russia, Lat. Q.v.III. 1, where the peridexion appears as marginalia, the only one in the entire manuscript, as no space was left for a miniature after the text was written.[8] Later depictions in bestiaries show the serpent as a snake squeezing through the trunk, or hissing from beneath the tree. The latter is found in the Bern Physiologus. Others depict two dragons, posed symmetrically, with the doves also symmetrical in the tree.[3]

It has also featured in European architecture, including a capital originally from Troyes, which depicts the form with two dragons.[9]

Its imagery is referenced on the Gniezno doors at Gniezno cathedral, where the doves sheltering in the tree are paralleled with Saint Adalbert of Prague taking shelter at a monastery in Rome. This depiction differs from typical medieval depictions, as the dragon is not representative of Satan but the Baltic Prussians Adalbert sought to convert to Christianity, and the tree is topped by a cockerel in an allusion to the Denial of Peter. Here, Adalbert needs to leave the safety of the tree for his mission, which is the opposite of the original meaning of the fable.[10]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "περιδέξιος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Revised and augmented by Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ "Folio 64v - Of bees, continued. De arbore que dicitur perindens; Of the tree called perindens". The Aberdeen Bestiary. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Wheatcroft, J. Holli (2013). Hassig, Debra (ed.). The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature. New York: Routledge. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-1-135-66038-3. OCLC 861692797.

- ^ Physiologus. Michael J. Curley. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2009. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-226-12871-9. OCLC 489110740.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Dines, Ilya (2007). "A French modeled English bestiary: Wormsley Library MS BM 3747". Mediaevistik. 20: 37–47. ISSN 0934-7453.

- ^ Physiologus griechisch/deutsch (in German). Otto Schönberger. Stuttgart: Reclam. 2001. p. 122. ISBN 978-3-15-018124-9. OCLC 231872028.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kulik, Alexander (2010). 3 Baruch: Greek-Slavonic Apocalypse of Baruch. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 194. ISBN 978-3-11-021249-5. OCLC 635947403.

- ^ a b Morrison, Elizabeth (2019). Book of Beasts: the Bestiary in the Medieval World. Larisa Grollemond. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-1-60606-590-7. OCLC 1049576705.

- ^ Mâle, Emile (1913). Religious art in France, XIII century: a Study in Mediaeval Iconography and its sources of inspiration. Translated by Nussey, Dora. London: J.M. Dent. pp. 45–46. OCLC 987722723.

- ^ Węcławowicz, Tomasz (2020). "The "Forest of Symbols" on the Romanesque bronze doors at Gniezno Cathedral Church". Romanesque Saints, Shrines, and Pilgrimage (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 261. ISBN 9780429260162.