Jewish fascism

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by 50.49.137.211 (talk | contribs) 0 seconds ago. (Update timer) |

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

Jewish fascism is a term that applies to Jewish political factions on the far-right wing of the political spectrum that have either actively associated themselves with or have been construed as engendering fascism.

An early example of Jewish fascism was the short-lived Revisionist Maximalism movement that arose within the Brit HaBirionim faction of the Zionist Revisionist Movement (ZRM) in the 1930s and which openly espoused its fascist values and goals.

In the 21st century, the Otzma Yehudit or Jewish Power party has been characterized as an example or resurgent fascism or neo-fascism.

Revisionist Maximalism[edit]

Revisionist Maximalism was a short-lived right-wing militant political ideology that was part of the Brit HaBirionim faction of the Zionist Revisionist Movement created by Abba Ahimeir. In 1930, Brit HaBirionim under Ahimeir's leadership publicly declared their desire to form a fascist state at the conference of the ZRM, saying:

"It is not the masses whom we need ... but the minorities ... We want to educate people for the 'Great Day of God' (war or world revolution), so that they will be ready to follow the leader blindly into the greatest danger ... Not a party but an Orden, a group of private [people], devoting themselves and sacrificing themselves for the great goal. They are united in all, but their private lives and their livelihood are the matter of the Orden. Iron discipline; cult of the leader (on the model of the fascists); dictatorship." (Abba Achimeir, 1930)[1]

The Revisionist Maximalist movement borrowed principles from totalitarianism, fascism and inspiration from Józef Piłsudski's Poland and Benito Mussolini's Italy.[2] Revisionist Maximalists strongly supported the Italian fascist regime of Benito Mussolini and wanted the creation of a Jewish state based on fascist principles.[3]

The Maximalist goal was to "extract Revisionism from its liberal entrapment", as they wanted Ze'ev Jabotinsky's status to be elevated to a dictator,[4] and desired to force integrate the population of Palestine into Hebrew society.[5] The Maximalists believed that authoritarianism and national solidarity was necessary to have the public collaborate with the government, and to create total unity in Palestine.[5]

The label of "fascist" has nevertheless to be regarded with reserves because in that period as later it was used often abusively in the disputes between opposed political non-fascist factions, as in the 1930s even the Social Democrat parties were accused by Stalin and the communists of being "fascists" or "social-fascists". In the same way in Palestine Revisionist Zionists themselves were often qualified in the 1930s as "fascists" by the Labor Zionist leaders and the Revisionists attacked the social democratic dominated General Confederation of Labor (Histadrut) and Ben Gurion by use of terms like "Red Swastika" and comparisons with fascism and Hitler.[6][7]

In 1932, Brit HaBirionim pressed the ZRM to adopt their policies which were titled the "Ten Commandments of Maximalism", which were made under "In the spirit of Complete Fascism", according to Stein Uglevik.[1] Moderate ZRM members refused to accept this and moderate ZRM member Yaacov Kahan pressured Brit HaBirionim to accept the democratic nature of the ZRM and not push for the party to adopt fascist dictatorial policies.[1]

The Revisionist Maximalists became the largest faction in the ZRM in 1930 but collapsed in support in 1933 after Ahimeir's support for the assassination of Hayim Arlosoroff.[8]

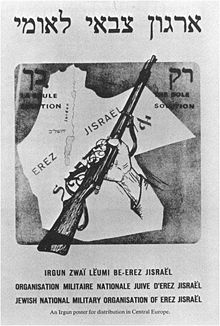

Far right politics in Mandatory Palestine (1920–1948)[edit]

Prior to the establishment of Israel, far-right Jewish groups were based on Revisionist Zionism, which promoted the Jewish right to sovereignty over all of Mandatory Palestine through the use of armed struggle.[9] Revisionist Zionism's ideological and cultural roots were influenced by Italian fascism. Ze'ev Jabotinsky, the founder of Revisionist Zionism, believed that Britain could no longer be trusted to advance Zionism, and that Fascist Italy, as a growing political challenger to Britain, was therefore an ally.[10][11]

Israel (1948 to 2020)[edit]

Far-right politics in Israel encompasses ideologies such as ultranationalism, Jewish supremacy, Jewish fascism, Jewish fundamentalism, Anti-Arabism,[12] anti-Palestinianism, and ideological movements such as Kahanism

Kach party (1971–1994)[edit]

The Kach party, founded by Meir Kahane in 1971, was a far-right Orthodox Jewish, Religious Zionist political party in Israel. The party's ideology, known as Kahanism, advocated the transfer of the Arab population from Israel, and the creation of a Jewish theocratic state, in which only Jews have voting rights.[13]

Otzma Yehudit[edit]

In the 21st century, Otzma Yehudit or Jewish Power, a religious Zionist political party led by Kahanists, has been characterized as being a fascistic in nature.[14][15] Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz has called Otzma Yehudit leader Itamar Ben Gvir representative of Jewish fascism.[16]

This aspect of its ideology is often described as being inherited from the Kach movement,[17][18] and as having been propelled to the fore by Netanyahu's bringing of religious Zionist parties into government.[19][20]

Oslo Accords[edit]

The far-right in Israel opposed the Oslo Accords, with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin being assassinated in 1995 by a right-wing Israeli extremist for signing them.[21] Yigal Amir, Rabin's assassin, had opposed Rabin's peace process, particularly the signing of the Oslo Accords, because he felt that an Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank would deny Jews their "biblical heritage which they had reclaimed by establishing settlements".[22] Rabin was also criticized by right-wing conservatives and Likud leaders who perceived the peace process as an attempt to forfeit the occupied territories and a surrender to Israel's enemies.[23][24] After the murder, it was revealed that Avishai Raviv, a well-known right-wing extremist at the time, was a Shin Bet agent and informant.[25] Prior to Rabin's murder, Raviv was filmed with a poster of Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in an SS uniform.[26][27][28] His mission was to monitor the activities of right-wing extremists, and he allegedly knew of Yigal Amir's plans to assassinate Rabin.[29]

Israeli politics in the 2020s[edit]

In association with the 2023 Israeli judicial reform the Likud-led Thirty-seventh government of Israel was frequently described as "Fascist" or "Dictatorial".[30][31][32] During that time the Likud-led far-right coalition were compared to Germany in 1930s, by journalists and historians within in Israel.[31][33] Including by Daniel Blatman, an Israeli historian, specializing in history of the Holocaust, [34] and head of the Institute for Contemporary Jewry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[35] When interviewed by Ayelett Suhani for Haaretz, Blatman said "Israel's government has neo-Nazi ministers. It really does recall Germany in 1933".[33] However, it should be noted he was referring specifically to the authoritarian aspects of that time and place.[33] These comments redirected some attention in the middle east, but somehow went unnoticed in Western Media.

Also during 2023 (but almost always separately), many people expressed concern that the policies and actions of the Israeli far right would lead to a "third intifada". Such as Haaretz journalist Amos Harel.[36] But this commentary went largely unnoticed outside of Israel and the middle east.[37] In 2024, many individuals and groups on the far-right in Israel are advocating for the reoccupation of Gaza following the Israel-Hamas war.[38]

December 2022 cabinet of Israel[edit]

The 37th Cabinet of Israel, formed on 29 December 2022, following the Knesset election on 1 November 2022, has been described as the most right-wing government in Israeli history,[39][40][41][42] as well as Israel's most religious government.[43][44] The coalition government consists of seven parties—Likud, United Torah Judaism, Shas, Religious Zionist Party, Otzma Yehudit, Noam, and National Unity—and is led by Benjamin Netanyahu.[45]

Judicial reforms[edit]

In 2023, as part of a campaign for judicial reform, a bill known as the "reasonableness" bill was passed in Israel. This controversial law limited the power of the Supreme Court to declare government decisions unreasonable.[46] In one instance, more than 80,000 Israeli protesters rallied in Tel Aviv against the far-right government's plans to overhaul the judicial system.[47] In early 2024, the Supreme Court of Israel struck down the reform[48] on the grounds that it would deal a "severe and unprecedented blow to the core characteristics of the State of Israel as a democratic state".[49]

Allegations of fascism and comparisons to past reigemes[edit]

During 2022 and 2023 the Likud-led far right coalition was frequently described as "Fascist" or a dictatorship, and other references to extreme authoritarianism, such as "Stalinist" (the authoritarian aspects of Stalin, not the economics).[50]

In February 2023 Yossi Klein said, "Protests are for a democracy. Protests aren't effective in a dictatorship, and the dictatorship is already here," in a Haaretz opinion piece titled "Germany 1933, Israel 2023".[31]

Commentary on Israeli politics in the 2020s[edit]

| Date | Title | Publication | Author or person interviewed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-02-10 | Israel’s government has neo-Nazi ministers. It really does recall Germany in 1933 | Daniel Blatman interviewed by Ayelett Suhani | [33] | |

| 2023-02-17 | Germany 1933, Israel 2023 | Yossi Klein | [31] | |

| 2023-02-10 | Do not march blindly into dictatorship | Yossi Klein | [30] | |

| 2023-10-03 | Neo-Fascism threatens Israelis and Palestinians alike | Elias Zananiri | [32] | |

| 2023-02-13 | Unsure if Israel is a democracy foreign investors are fleeing the apartheid state | [51] |

Predicted provocation of a "third intifada" in 2022 and 2023[edit]

Also during 2023 (but almost always separately), many people expressed concern that the policies and actions of the Israeli far right would lead to a "third intifada". Such as Haaretz journalist Amos Harel.[36]

Today, many individuals and groups on the far-right in Israel are advocating for the reoccupation of Gaza following the Israel-Hamas war.[52]

In March 2023 Yoav Gallant warned that something like 7 October attacks was looming, and was almost fired by Netanyahu for doing so.[53]

Genocidal Rhetoric[edit]

Defence minister Yoav Galant, who is usually regarded as a moderate, made extremist statents at the onset of the war, that were precieved by many as incitement to war crimes, or even genocidal. On 9 October 2023 Yoav Galant made a speech which many have described as genocidal.[54][55]

“I have ordered a complete siege on the Gaza Strip. There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel, everything is closed. We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly,” [56][57]

In a piece for Jewish Currents, Raz Segal (an associate professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Stockton University and the endowed professor in the study of modern genocide)[58] described the assault on Gaza can also be understood in other terms: as "a textbook case of genocide".[59]

Criticism of far-right politics in Israel[edit]

Several journalists and human rights groups such as B'Tselem, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch claim that the ideology advocated by the Israeli far-right are fascist and racist towards Palestinians, Arab citizens of Israel and immigrants. They see it as a danger to democracy, and claim that it uses violence and encourages violation of human rights.[60][61][62][63] President of the United States Joe Biden said Benjamin Netanyahu's government contained "some of the most extreme" members he had ever seen.[64]

See also[edit]

- Criticism of Israel

- Criticism of Judaism

- Anti-Zionism

- Zionism

- History of Zionism

- Revisionist Zionism

- Fascism in Asia

- Kahanism

- Revisionist Maximalism

- Alt-right

- Far-right politics in Israel

- One-state solution

- Israeli settler violence

- Israeli war crimes

- Population transfer

- Palestinian genocide accusation

- Racism in Asia

- Racism in Israel

- Racism in Jewish communities

- Xenophobia and racism in the Middle East

- Zionist political violence

- Halachic state

- Jewish extremist terrorism

- Jewish fundamentalism

- Jewish views on religious pluralism

- Judaism and violence

- Judaism and politics

- Politics of Israel

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Larsen, p377.

- ^ Shlaim, Avi (1996). Shindle, Colin; Shamir, Yitzhak; Arens, Moshe; Begin, Ze‘ev B.; Netanyahu, Benjamin (eds.). "The Likud in Power: The Historiography of Revisionist Zionism". Israel Studies. 1 (2): 279. ISSN 1084-9513.

- ^ Larsen, Stein Ugelvik (ed.). Fascism Outside of Europe. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-88033-988-8. pp. 364-365.

- ^ Naor, Arye (2006). "Review of The Triumph of Military Zionism: Nationalism and the Origins of the Israeli Right". Israel Studies. 11 (3): 176. ISSN 1084-9513.

- ^ a b TAMIR, DAN (2014). "FROM A FASCIST'S NOTEBOOK TO THE PRINCIPLES OF REBIRTH: THE DESIRE FOR SOCIAL INTEGRATION IN HEBREW FASCISM, 1928–1942". The Historical Journal. 57 (4): 1080. ISSN 0018-246X.

- ^ Douglas Feith Book Review:Jabotinsky by Hillel Halkin Wall Street Journal 30 may 2014

- ^ Yaacov Shavit Jabotinsky and the Revisionist Movement 1925-1948 p.336 and the XIIth ch Revisionism and Fascism - Image and Interpretation p.349 and al.in Oxon, England, UK: Frank Cass & Co, Ltd.,1988

- ^ "The Assassination of Hayim Arlosoroff". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- ^ Zouplna, Jan (2008). "Revisionist Zionism: Image, Reality and the Quest for Historical Narrative". Middle Eastern Studies. 44 (1): 3–27. doi:10.1080/00263200701711754. ISSN 0026-3206.

- ^ Kaplan, Eran (2005). The Jewish radical right: Revisionist Zionism and its ideological legacy. Studies on Israel. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 21, 149–150, 156. ISBN 978-0-299-20380-1.

- ^ Brenner, Lenni (1983). "Zionism-Revisionism: The Years of Fascism and Terror". Journal of Palestine Studies. 13 (1): 66–92. doi:10.2307/2536926. JSTOR 2536926 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Sprinzak, Ehud (1993). The Israeli Radical Right: History, Culture, and Politics (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 2, 22–23. ISBN 9780429034404.

- ^ Martin, Gus; Kushner, Harvey W., eds. (2011). The Sage encyclopedia of terrorism (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-4129-8016-6.

- ^ Zogby, James (23 March 2021). "Netanyahu Is Letting Israel's Fascists Enter by the Front Door". The Nation.

- ^ Solomon, Esther (10 September 2023). "When a Jewish Fascist Moves Into Your Neighborhood". Haaretz.

- ^ Illouz, Eva (15 November 2022). "La troisième force politique en Israël représente ce que l'on est bien obligé d'appeler, à contrecœur, un "fascisme juif"". Le Monde (in French).

- ^ Khatib, Ibrahim (28 July 2022). "Kahane Movement: Origins and Influence on Israeli Politics".

If the Kach Movement and its legacy represent fascism and racism, this fascist legacy has been transmitted and continues to be passed on to certain Israeli people, parties and movements, as is the case with Otzma Yehudit and other more radical movements, including the Hilltop Youth Group, Lahava, and La Familia.

} - ^ Liba, Dror (21 February 2019). "Otzma Yehudit's history of racism and provocation". Ynet.

- ^ Horowitz, Amiad (2022). "Israeli extremists propelled to power alongside Netanyahu, accelerating global neo-fascist trend". 12 (12). Guardian (Sydney). doi:10.3316/informit.738903440185836.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Khaled, T. (2022). "A Palestinian Perspective on the Recent Israeli Elections". Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture. 27 (3/4): 152–157.

- ^ Rabin, Leah (1997). Rabin: His Life, Our Legacy. G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 7, 11–12. ISBN 0-399-14217-7.

- ^ Smith, Charles D. Palestine and the Arab-Israeli Conflict A History with Documents, ISBN 0-312-43736-6, pp. 458

- ^ Newton, Michael (2014). "Rabin, Yitzhak". Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-61-069285-4.

- ^ Tucker, Ernest (2016). The Middle East in Modern World History. Routledge. pp. 331–32. ISBN 978-1-31-550823-8.

- ^ Ephron, Dan (2015). Killing a king: the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and the remaking of Israel (1st ed.). New York London: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-393-24209-6.

- ^ Barnea, Avner (2017-01-02). "The Assassination of a Prime Minister–The Intelligence Failure that Failed to Prevent the Murder of Yitzhak Rabin". The International Journal of Intelligence, Security, and Public Affairs. 19 (1): 37. doi:10.1080/23800992.2017.1289763. ISSN 2380-0992.

- ^ Hellinger, Moshe; Hershkowitz, Isaac; Susser, Bernard (2018). Religious Zionism and the settlement project: ideology, politics, and civil disobedience. Albany: SUNY Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-4384-6839-6.

- ^ Ex-Undercover Agent Charged as a Link in Rabin Killing, The New York Times, April 26, 1999

- ^ Cohen-Almagor, Raphael (2006). The scope of tolerance: studies on the costs of free expression and freedom of the press. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-415-35758-6.

- ^ a b Klein, Yossi (10 February 2023). "Do not march blindly into dictatorship". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Klein, Yossi (17 February 2023). "Germany 1933, Israel 2023". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ a b Zananiri, Elias (3 October 2023). "Israeli Neo-Fascism threatens Israelis and Palestinians alike". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Shani, Ayelett (10 February 2023). "'Israel's government has neo-Nazi ministers. It really does recall Germany in 1933'". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ushmmbiowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Dr. Daniel Blatman — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ^ a b Harel, Amos (3 February 2023). "Will far-right minister Itamar Ben-Gvir's chutzpah trigger a third intifada?". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "A Third Intifada could be coming, but you won't learn about it in the New York Times". Mondoweiss. 5 December 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ Peled, Margherita Stancati and Anat. "Israel's Far Right Plots a 'New Gaza' Without Palestinians". WSJ. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ * Kershner, Isabel; Kingsley, Patrick (1 November 2022). "Israel Election: Exit Polls Show Netanyahu With Edge in Israel's Election". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Reich, Eleanor H. (16 November 2022). "Israel swears in new parliament, most right-wing in history". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 7 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Shalev, Tal (3 February 2023). "The most right-wing coalition in Israel's history had a stormy first month". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ * "Israel Swears in New Parliament, Most Right-Wing in History". U.S. News & World Report. Associated Press (AP). 2022. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

Israel has sworn in its most religious and right-wing parliament

- Lieber, Dov; Raice, Shayndi; Boxerman, Aaron (2022). "Behind Benjamin Netanyahu's Win in Israel: The Rise of Religious Zionism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

Israel's most right-wing and religious government in its history

- "Netanyahu Government: West Bank Settlements Top Priority". VOA. Associated Press (AP). 2022. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

the most religious and hardline in Israel's history

- Lieber, Dov; Raice, Shayndi; Boxerman, Aaron (2022). "Behind Benjamin Netanyahu's Win in Israel: The Rise of Religious Zionism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Carrie Keller-Lynn (21 December 2022). ""I've done it": Netanyahu announces his 6th government, Israel's most hardline ever". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Tal, Rob Picheta,Hadas Gold,Amir (29 December 2022). "Benjamin Netanyahu sworn in as leader of Israel's likely most right-wing government ever". CNN. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ * Maltz, Judy (3 November 2022). "Will Israel Become a Theocracy? Religious Parties Are Election's Biggest Winners". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- Levinthal, Batya (4 January 2023). "Poll: 70% of secular Israelis worry about their future under new gov". i24News. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

Netanyahu's new government, deemed the most religious and right-wing in the country's history.

- Levinthal, Batya (4 January 2023). "Poll: 70% of secular Israelis worry about their future under new gov". i24News. Archived from the original on 11 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Gross, Judah Ari (4 November 2022). "Israel poised to have its most religious government; experts say no theocracy yet". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 6 November 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Elections and Parties". en.idi.org.il. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ Gold, Hadas; Greene, Richard Allen; Tal, Amir (2023-07-24). "Israel passed a bill to limit the Supreme Court's power. Here's what comes next". CNN. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ McGarvey, Emily (2023-01-14). "Over 80,000 Israelis protest against Supreme Court reform". BBC. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (2024-01-03). "Israel's Supreme Court just overturned Netanyahu's pre-war power grab". Vox. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ Edwards, Christian (2024-01-02). "What we know about Israel's Supreme Court ruling on Netanyahu's judicial overhaul". CNN. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- ^ https://www.haaretz.com/opinion/2023-01-12/ty-article-opinion/.premium/netanyahus-stalinist-purge-threatens-israeli-democracy/00000185-a2b0-d7cf-afef-a6fa4b1e0000

- ^ https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20230213-unsure-if-israel-is-a-democracy-foreign-investors-are-fleeing-the-apartheid-state/

- ^ Peled, Margherita Stancati and Anat. "Israel's Far Right Plots a 'New Gaza' Without Palestinians". WSJ. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Tibon, Amir (16 May 2024). "Israel's real problem is that Netanyahu and his far-right allies prefer Hamas". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "'Human Animals': The sordid language behind Israel's genocide in Gaza". Middle East Monitor. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Green, Raz Segal,Penny (14 January 2024). "Intent in the genocide case against Israel is not hard to prove". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

A database of more than 500 statements showing Israeli incitement to genocide provides ample evidence of genocidal intent.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Defense minister announces 'complete siege' of Gaza: No power, food or fuel". 9 October 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "Israeli defence minister orders 'complete siege' on Gaza (video of speech in Hebrew with English subtitles)". Al Jazeera. 9 October 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "Raz Segal - author profile". Jewish Currents. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "A Textbook Case of Genocide". Jewish Currents. 13 October 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ Guyer, Jonathan (2023-01-20). "Israel's new right-wing government is even more extreme than protests would have you think". Vox. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ Shakir, Omar (2021-04-27). "A Threshold Crossed". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ "Who is Israel's far-right, pro-settler Security Minister Ben-Gvir?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ Nechin, Etan (2024-01-09). "The far right infiltration of Israel's media is blinding the public to the truth about Gaza". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ Gritten, David (2023-07-10). "Biden criticises 'most extreme' ministers in Israeli government". BBC. Retrieved 2024-03-23.