Wikipedia

The logo of Wikipedia, a globe featuring glyphs from various writing systems such as Latin, Greek, Devanagari, Chinese, Arabic, and others | |

Type of site | Online encyclopedia |

|---|---|

| Available in | 329 languages |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Owner | |

| Created by | |

| URL | wikipedia |

| Commercial | No |

| Registration | Optional[note 1] |

| Users | >290,069 active editors[note 2] >113,633,550 registered users |

| Launched | January 15, 2001 |

| Current status | Active |

Content license | CC Attribution / Share-Alike 4.0 Most text is also dual-licensed under GFDL; media licensing varies |

| Written in | LAMP platform[2] |

| OCLC number | 52075003 |

Wikipedia[note 3] is a free content online encyclopedia written and maintained by a community of volunteers, known as Wikipedians, through open collaboration and the use of the wiki-based editing system MediaWiki. Wikipedia is the largest and most-read reference work in history.[3][4] It is consistently ranked as one of the ten most popular websites in the world, and as of 2024 is ranked the fifth most visited website on the Internet by Semrush,[5] and second by Ahrefs.[6] Founded by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger on January 15, 2001, Wikipedia is hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation, an American nonprofit organization that employs a staff of over 700 people.[7]

Initially only available in English, editions in other languages have been developed. Wikipedia's editions, when combined, comprise more than 62 million articles, attracting around 2 billion unique device visits per month and more than 14 million edits per month (about 5.2 edits per second on average) as of November 2023[update].[8][W 1] Roughly 26% of Wikipedia's traffic is from the United States, followed by Japan at 5.9%, the United Kingdom at 5.4%, Germany at 5%, Russia at 4.8%, and the remaining 54% split among other countries, according to data provided by Similarweb.[9]

Wikipedia has been praised for its enablement of the democratization of knowledge, extent of coverage, unique structure, and culture. It has been criticized for exhibiting systemic bias, particularly gender bias against women and geographical bias against the Global South (Eurocentrism).[10][11][failed verification] While the reliability of Wikipedia was frequently criticized in the 2000s, it has improved over time, receiving greater praise from the late 2010s onward[3][10][12] while becoming an important fact-checking site.[13][14]

Wikipedia has been censored by some national governments, ranging from specific pages to the entire site.[15][16] Articles on breaking news are often accessed as sources for frequently updated information about those events.[17][18]

History

Nupedia

Various collaborative online encyclopedias were attempted before the start of Wikipedia, but with limited success.[19] Wikipedia began as a complementary project for Nupedia, a free online English-language encyclopedia project whose articles were written by experts and reviewed under a formal process.[20] It was founded on March 9, 2000, under the ownership of Bomis, a web portal company. Its main figures were Bomis CEO Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger, editor-in-chief for Nupedia and later Wikipedia.[1][21] Nupedia was initially licensed under its own Nupedia Open Content License, but before Wikipedia was founded, Nupedia switched to the GNU Free Documentation License at the urging of Richard Stallman.[W 2] Wales is credited with defining the goal of making a publicly editable encyclopedia,[22][W 3] while Sanger is credited with the strategy of using a wiki to reach that goal.[W 4] On January 10, 2001, Sanger proposed on the Nupedia mailing list to create a wiki as a "feeder" project for Nupedia.[W 5]

Launch and growth

The domains wikipedia.org and wikipedia.com (later redirecting to wikipedia.org) were registered on January 13, 2001,[W 6] and January 12, 2001,[W 7] respectively. Wikipedia was launched on January 15, 2001[20] as a single English-language edition at www.wikipedia.com,[W 8] and was announced by Sanger on the Nupedia mailing list.[22] The name originated from a blend of the words wiki and encyclopedia.[23][24] Its integral policy of "neutral point-of-view"[W 9] was codified in its first few months. Otherwise, there were initially relatively few rules, and it operated independently of Nupedia.[22] Bomis originally intended for it to be a for-profit business.[25]

Wikipedia gained early contributors from Nupedia, Slashdot postings, and web search engine indexing. Language editions were created beginning in March 2001, with a total of 161 in use by the end of 2004.[W 10][W 11] Nupedia and Wikipedia coexisted until the former's servers were taken down permanently in 2003, and its text was incorporated into Wikipedia. The English Wikipedia passed the mark of two million articles on September 9, 2007, making it the largest encyclopedia ever assembled, surpassing the Yongle Encyclopedia made in China during the Ming dynasty in 1408, which had held the record for almost 600 years.[26]

Citing fears of commercial advertising and lack of control, users of the Spanish Wikipedia forked from Wikipedia to create Enciclopedia Libre in February 2002.[W 12] Wales then announced that Wikipedia would not display advertisements, and changed Wikipedia's domain from wikipedia.com to wikipedia.org.[27][W 13]

Though the English Wikipedia reached three million articles in August 2009, the growth of the edition, in terms of the numbers of new articles and of editors, appears to have peaked around early 2007.[28] Around 1,800 articles were added daily to the encyclopedia in 2006; by 2013 that average was roughly 800.[W 14] A team at the Palo Alto Research Center attributed this slowing of growth to the project's increasing exclusivity and resistance to change.[29] Others suggest that the growth is flattening naturally because articles that could be called "low-hanging fruit"—topics that clearly merit an article—have already been created and built up extensively.[30][31][32]

In November 2009, a researcher at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid, Spain found that the English Wikipedia had lost 49,000 editors during the first three months of 2009; in comparison, it lost only 4,900 editors during the same period in 2008.[33][34] The Wall Street Journal cited the array of rules applied to editing and disputes related to such content among the reasons for this trend.[35] Wales disputed these claims in 2009, denying the decline and questioning the study's methodology.[36] Two years later, in 2011, he acknowledged a slight decline, noting a decrease from "a little more than 36,000 writers" in June 2010 to 35,800 in June 2011. In the same interview, he also claimed the number of editors was "stable and sustainable".[37] A 2013 MIT Technology Review article, "The Decline of Wikipedia", questioned this claim, revealing that since 2007, Wikipedia had lost a third of its volunteer editors, and that those remaining had focused increasingly on minutiae.[38] In July 2012, The Atlantic reported that the number of administrators was also in decline.[39] In the November 25, 2013, issue of New York magazine, Katherine Ward stated, "Wikipedia, the sixth-most-used website, is facing an internal crisis."[40]

The number of active English Wikipedia editors has since remained steady after a long period of decline.[41][42]

Milestones

In January 2007, Wikipedia first became one of the ten most popular websites in the United States, according to Comscore Networks.[43] With 42.9 million unique visitors, it was ranked #9, surpassing The New York Times (#10) and Apple (#11).[43] This marked a significant increase over January 2006, when Wikipedia ranked 33rd, with around 18.3 million unique visitors.[44] In 2014, it received eight billion page views every month.[W 15] On February 9, 2014, The New York Times reported that Wikipedia had 18 billion page views and nearly 500 million unique visitors a month, "according to the ratings firm comScore".[8] As of March 2023[update], it ranked 6th in popularity, according to Similarweb.[45] Loveland and Reagle argue that, in process, Wikipedia follows a long tradition of historical encyclopedias that have accumulated improvements piecemeal through "stigmergic accumulation".[46][47]

On January 18, 2012, the English Wikipedia participated in a series of coordinated protests against two proposed laws in the United States Congress—the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and the PROTECT IP Act (PIPA)—by blacking out its pages for 24 hours.[48] More than 162 million people viewed the blackout explanation page that temporarily replaced its content.[49][W 16]

In January 2013, 274301 Wikipedia, an asteroid, was named after Wikipedia;[50] in October 2014, Wikipedia was honored with the Wikipedia Monument;[51] and, in July 2015, 106 of the 7,473 700-page volumes of Wikipedia became available as Print Wikipedia.[52] In April 2019, an Israeli lunar lander, Beresheet, crash landed on the surface of the Moon carrying a copy of nearly all of the English Wikipedia engraved on thin nickel plates; experts say the plates likely survived the crash.[53][54] In June 2019, scientists reported that all 16 GB of article text from the English Wikipedia had been encoded into synthetic DNA.[55]

On January 20, 2014, Subodh Varma reporting for The Economic Times indicated that not only had Wikipedia's growth stalled, it "had lost nearly ten percent of its page views last year. There was a decline of about two billion between December 2012 and December 2013. Its most popular versions are leading the slide: page-views of the English Wikipedia declined by twelve percent, those of German version slid by 17 percent and the Japanese version lost nine percent."[56] Varma added, "While Wikipedia's managers think that this could be due to errors in counting, other experts feel that Google's Knowledge Graphs project launched last year may be gobbling up Wikipedia users."[56] When contacted on this matter, Clay Shirky, associate professor at New York University and fellow at Harvard's Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society said that he suspected much of the page-view decline was due to Knowledge Graphs, stating, "If you can get your question answered from the search page, you don't need to click [any further]."[56] By the end of December 2016, Wikipedia was ranked the fifth most popular website globally.[57]

As of January 2023, 55,791 English Wikipedia articles have been cited 92,300 times in scholarly journals,[58] from which cloud computing was the most cited page.[59]

On January 18, 2023, Wikipedia debuted a new website redesign, called "Vector 2022".[60][61] It featured a redesigned menu bar, moving the table of contents to the left as a sidebar, and numerous changes in the locations of buttons like the language selection tool.[61][W 17] The update initially received backlash, most notably when editors of the Swahili Wikipedia unanimously voted to revert the changes.[60][62]

Openness

Unlike traditional encyclopedias, Wikipedia follows the procrastination principle regarding the security of its content, meaning that it waits until a problem arises to fix it.[63]

Restrictions

Due to Wikipedia's increasing popularity, some editions, including the English version, have introduced editing restrictions for certain cases. For instance, on the English Wikipedia and some other language editions, only registered users may create a new article.[W 18] On the English Wikipedia, among others, particularly controversial, sensitive, or vandalism-prone pages have been protected to varying degrees.[W 19][64] A frequently vandalized article can be "semi-protected" or "extended confirmed protected", meaning that only "autoconfirmed" or "extended confirmed" editors can modify it.[W 19] A particularly contentious article may be locked so that only administrators can make changes.[W 20] A 2021 article in the Columbia Journalism Review identified Wikipedia's page-protection policies as "perhaps the most important" means at its disposal to "regulate its market of ideas".[65]

In certain cases, all editors are allowed to submit modifications, but review is required for some editors, depending on certain conditions. For example, the German Wikipedia maintains "stable versions" of articles which have passed certain reviews.[W 21] Following protracted trials and community discussion, the English Wikipedia introduced the "pending changes" system in December 2012.[66] Under this system, new and unregistered users' edits to certain controversial or vandalism-prone articles are reviewed by established users before they are published.[67]

Review of changes

Although changes are not systematically reviewed, Wikipedia's software provides tools allowing anyone to review changes made by others. Each article's History page links to each revision.[note 5][68] On most articles, anyone can view the latest changes and undo others' revisions by clicking a link on the article's History page. Registered users may maintain a "watchlist" of articles that interest them so they can be notified of changes.[W 22] "New pages patrol" is a process where newly created articles are checked for obvious problems.[W 23]

In 2003, economics PhD student Andrea Ciffolilli argued that the low transaction costs of participating in a wiki created a catalyst for collaborative development, and that features such as allowing easy access to past versions of a page favored "creative construction" over "creative destruction".[69]

Vandalism

Any change that deliberately compromises Wikipedia's integrity is considered vandalism. The most common and obvious types of vandalism include additions of obscenities and crude humor; it can also include advertising and other types of spam.[70] Sometimes editors commit vandalism by removing content or entirely blanking a given page. Less common types of vandalism, such as the deliberate addition of plausible but false information, can be more difficult to detect. Vandals can introduce irrelevant formatting, modify page semantics such as the page's title or categorization, manipulate the article's underlying code, or use images disruptively.[W 24]

Obvious vandalism is generally easy to remove from Wikipedia articles; the median time to detect and fix it is a few minutes.[71][72] However, some vandalism takes much longer to detect and repair.[73]

In the Seigenthaler biography incident, an anonymous editor introduced false information into the biography of American political figure John Seigenthaler in May 2005, falsely presenting him as a suspect in the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[73] It remained uncorrected for four months.[73] Seigenthaler, the founding editorial director of USA Today and founder of the Freedom Forum First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, called Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales and asked whether he had any way of knowing who contributed the misinformation. Wales said he did not, although the perpetrator was eventually traced.[74][75] After the incident, Seigenthaler described Wikipedia as "a flawed and irresponsible research tool".[73] The incident led to policy changes at Wikipedia for tightening up the verifiability of biographical articles of living people.[76]

Edit warring

Wikipedians often have disputes regarding content, which may result in repeated competing changes to an article, known as "edit warring".[W 25][77] It is widely seen as a resource-consuming scenario where no useful knowledge is added,[78] and criticized as creating a competitive[79] and conflict-based editing culture associated with traditional masculine gender roles.[80][81]

Taha Yasseri of the University of Oxford examined editing conflicts and their resolution in a 2013 study.[82][83] Yasseri contended that simple reverts or "undo" operations were not the most significant measure of counterproductive work behavior at Wikipedia. He relied instead on "mutually reverting edit pairs", where one editor reverts the edit of another editor who then, in sequence, returns to revert the first editor. The results were tabulated for several language versions of Wikipedia. The English Wikipedia's three largest conflict rates belonged to the articles George W. Bush, anarchism, and Muhammad.[83] By comparison, for the German Wikipedia, the three largest conflict rates at the time of the study were for the articles covering Croatia, Scientology, and 9/11 conspiracy theories.[83]

Policies and content

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Content in Wikipedia is subject to the laws (in particular, copyright laws) of the United States and of the US state of Virginia, where the majority of Wikipedia's servers are located.[W 26][W 27] By using the site, one agrees to the Wikimedia Foundation Terms of Use and Privacy Policy; some of the main rules are that contributors are legally responsible for their edits and contributions, that they should follow the policies that govern each of the independent project editions, and they may not engage in activities, whether legal or illegal, that may be harmful to other users.[W 28][W 29] In addition to the terms, the Foundation has developed policies, described as the "official policies of the Wikimedia Foundation".[W 30]

The fundamental principles of the Wikipedia community are embodied in the "Five pillars", while the detailed editorial principles are expressed in numerous policies and guidelines intended to appropriately shape content.[W 31] The five pillars are:

- Wikipedia is an encyclopedia

- Wikipedia is written from a neutral point of view

- Wikipedia is free content that anyone can use, edit, and distribute

- Wikipedia's editors should treat each other with respect and civility

- Wikipedia has no firm rules

The rules developed by the community are stored in wiki form, and Wikipedia editors write and revise the website's policies and guidelines in accordance with community consensus.[84] Editors can enforce the rules by deleting or modifying non-compliant material.[W 32] Originally, rules on the non-English editions of Wikipedia were based on a translation of the rules for the English Wikipedia. They have since diverged to some extent.[W 21]

The two most commonly used namespaces across all editions of Wikipedia are: The article namespace (which are the articles of the encyclopedia) and the category namespace (which is a collection of pages such as articles). In addition, there have been various books and reading lists that are composed completely of articles and categories of a certain Wikipedia.

Content policies and guidelines

According to the rules on the English Wikipedia community, each entry in Wikipedia must be about a topic that is encyclopedic and is not a dictionary entry or dictionary-style.[W 33] A topic should also meet Wikipedia's standards of "notability", which generally means that the topic must have been covered in mainstream media or major academic journal sources that are independent of the article's subject.[W 34] Further, Wikipedia intends to convey only knowledge that is already established and recognized.[W 35] It must not present original research.[W 36] A claim that is likely to be challenged requires a reference to a reliable source, as do all quotations.[W 33] Among Wikipedia editors, this is often phrased as "verifiability, not truth" to express the idea that the readers, not the encyclopedia, are ultimately responsible for checking the truthfulness of the articles and making their own interpretations.[W 37] This can at times lead to the removal of information which, though valid, is not properly sourced.[85] Finally, Wikipedia must not take sides.[W 38]

Governance

Wikipedia's initial anarchy integrated democratic and hierarchical elements over time.[86][87] An article is not considered to be owned by its creator or any other editor, nor by the subject of the article.[W 39]

Administrators

Editors in good standing in the community can request extra user rights, granting them the technical ability to perform certain special actions. In particular, editors can choose to run for "adminship",[88] which includes the ability to delete pages or prevent them from being changed in cases of severe vandalism or editorial disputes.[W 40] Administrators are not supposed to enjoy any special privilege in decision-making; instead, their powers are mostly limited to making edits that have project-wide effects and thus are disallowed to ordinary editors, and to implement restrictions intended to prevent disruptive editors from making unproductive edits.[W 40]

By 2012, fewer editors were becoming administrators compared to Wikipedia's earlier years, in part because the process of vetting potential administrators had become more rigorous.[89] In 2022, there was a particularly contentious request for adminship over the candidate's anti-Trump views; ultimately, they were granted adminship.[90]

Dispute resolution

Over time, Wikipedia has developed a semiformal dispute resolution process. To determine community consensus, editors can raise issues at appropriate community forums, seek outside input through third opinion requests, or initiate a more general community discussion known as a "request for comment".[W 25]

Wikipedia encourages local resolutions of conflicts, which Jemielniak argues is quite unique in organization studies, though there has been some recent interest in consensus building in the field.[91] Joseph Reagle and Sue Gardner argue that the approaches to consensus building are similar to those used by Quakers.[91]: 62 A difference from Quaker meetings is the absence of a facilitator in the presence of disagreement, a role played by the clerk in Quaker meetings.[91]: 83

Arbitration Committee

The Arbitration Committee presides over the ultimate dispute resolution process. Although disputes usually arise from a disagreement between two opposing views on how an article should read, the Arbitration Committee explicitly refuses to directly rule on the specific view that should be adopted.[92] Statistical analyzes suggest that the committee ignores the content of disputes and rather focuses on the way disputes are conducted,[93] functioning not so much to resolve disputes and make peace between conflicting editors, but to weed out problematic editors while allowing potentially productive editors back in to participate.[92] Therefore, the committee does not dictate the content of articles, although it sometimes condemns content changes when it deems the new content violates Wikipedia policies (for example, if the new content is considered biased).[note 6] Commonly used solutions include cautions and probations (used in 63% of cases) and banning editors from articles (43%), subject matters (23%), or Wikipedia (16%).[92] Complete bans from Wikipedia are generally limited to instances of impersonation and anti-social behavior.[W 41] When conduct is not impersonation or anti-social, but rather edit warring and other violations of editing policies, solutions tend to be limited to warnings.[92]

Community

Each article and each user of Wikipedia has an associated and dedicated "talk" page. These form the primary communication channel for editors to discuss, coordinate and debate.[94]

Wikipedia's community has been described as cultlike,[95] although not always with entirely negative connotations.[96] Its preference for cohesiveness, even if it requires compromise that includes disregard of credentials, has been referred to as "anti-elitism".[W 42]

Wikipedia does not require that its editors and contributors provide identification.[97] As Wikipedia grew, "Who writes Wikipedia?" became one of the questions frequently asked there.[98] Jimmy Wales once argued that only "a community ... a dedicated group of a few hundred volunteers" makes the bulk of contributions to Wikipedia and that the project is therefore "much like any traditional organization".[99] In 2008, a Slate magazine article reported that: "According to researchers in Palo Alto, one percent of Wikipedia users are responsible for about half of the site's edits."[100] This method of evaluating contributions was later disputed by Aaron Swartz, who noted that several articles he sampled had large portions of their content (measured by number of characters) contributed by users with low edit counts.[101]

The English Wikipedia has 6,822,390 articles, 47,381,217 registered editors, and 122,835 active editors. An editor is considered active if they have made one or more edits in the past 30 days.[W 43]

Editors who fail to comply with Wikipedia cultural rituals, such as signing talk page comments, may implicitly signal that they are Wikipedia outsiders, increasing the odds that Wikipedia insiders may target or discount their contributions. Becoming a Wikipedia insider involves non-trivial costs: the contributor is expected to learn Wikipedia-specific technological codes, submit to a sometimes convoluted dispute resolution process, and learn a "baffling culture rich with in-jokes and insider references".[102] Editors who do not log in are in some sense "second-class citizens" on Wikipedia,[102] as "participants are accredited by members of the wiki community, who have a vested interest in preserving the quality of the work product, on the basis of their ongoing participation",[103] but the contribution histories of anonymous unregistered editors recognized only by their IP addresses cannot be attributed to a particular editor with certainty.[103]

Studies

A 2007 study by researchers from Dartmouth College found that "anonymous and infrequent contributors to Wikipedia ... are as reliable a source of knowledge as those contributors who register with the site".[104] Jimmy Wales stated in 2009 that "[I]t turns out over 50% of all the edits are done by just 0.7% of the users ... 524 people ... And in fact, the most active 2%, which is 1400 people, have done 73.4% of all the edits."[99] However, Business Insider editor and journalist Henry Blodget showed in 2009 that in a random sample of articles, most Wikipedia content (measured by the amount of contributed text that survives to the latest sampled edit) is created by "outsiders", while most editing and formatting is done by "insiders".[99]

A 2008 study found that Wikipedians were less agreeable, open, and conscientious than others,[105] although a later commentary pointed out serious flaws, including that the data showed higher openness and that the differences with the control group and the samples were small.[106] According to a 2009 study, there is "evidence of growing resistance from the Wikipedia community to new content".[107]

Diversity

Several studies have shown that most Wikipedia contributors are male. Notably, the results of a Wikimedia Foundation survey in 2008 showed that only 13 percent of Wikipedia editors were female.[108] Because of this, universities throughout the United States tried to encourage women to become Wikipedia contributors.[109] Similarly, many of these universities, including Yale and Brown, gave college credit to students who create or edit an article relating to women in science or technology.[109] Andrew Lih, a professor and scientist, said that the reason he thought the number of male contributors outnumbered the number of females so greatly was because identifying as a woman may expose oneself to "ugly, intimidating behavior".[citation needed][110] Data has shown that Africans are underrepresented among Wikipedia editors.[111]

Language editions

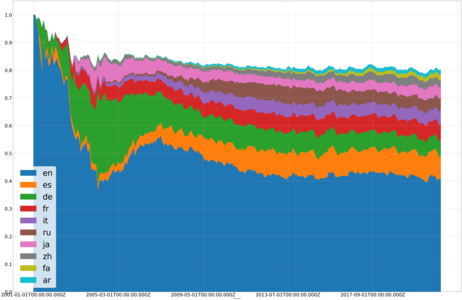

Distribution of the 62,957,694 articles in different language editions (as of May 10, 2024)[W 44]

There are currently 329 language editions of Wikipedia (also called language versions, or simply Wikipedias). As of May 2024, the six largest, in order of article count, are the English, Cebuano, German, French, Swedish, and Dutch Wikipedias.[W 45] The second and fifth-largest Wikipedias owe their position to the article-creating bot Lsjbot, which as of 2013[update] had created about half the articles on the Swedish Wikipedia, and most of the articles in the Cebuano and Waray Wikipedias. The latter are both languages of the Philippines. In addition to the top six, twelve other Wikipedias have more than a million articles each (Russian, Spanish, Italian, Egyptian Arabic, Polish, Chinese, Japanese, Ukrainian, Vietnamese, Waray, Arabic and Portuguese), seven more have over 500,000 articles (Persian, Catalan, Indonesian, Serbian, Korean, Norwegian and Turkish), 44 more have over 100,000, and 82 more have over 10,000.[W 46][W 45] The largest, the English Wikipedia, has over 6.8 million articles. As of January 2021,[update] the English Wikipedia receives 48% of Wikipedia's cumulative traffic, with the remaining split among the other languages. The top 10 editions represent approximately 85% of the total traffic.[W 47]

-

Most viewed editions of Wikipedia over time

-

Most edited editions of Wikipedia over time

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since Wikipedia is based on the Web and therefore worldwide, contributors to the same language edition may use different dialects or may come from different countries (as is the case for the English edition). These differences may lead to some conflicts over spelling differences (e.g. colour versus color)[W 48] or points of view.[W 49]

Though the various language editions are held to global policies such as "neutral point of view", they diverge on some points of policy and practice, most notably on whether images that are not licensed freely may be used under a claim of fair use.[W 50][113]

Jimmy Wales has described Wikipedia as "an effort to create and distribute a free encyclopedia of the highest possible quality to every single person on the planet in their own language".[W 51] Though each language edition functions more or less independently, some efforts are made to supervise them all. They are coordinated in part by Meta-Wiki, the Wikimedia Foundation's wiki devoted to maintaining all its projects (Wikipedia and others).[W 52] For instance, Meta-Wiki provides important statistics on all language editions of Wikipedia,[W 53] and it maintains a list of articles every Wikipedia should have.[W 54] The list concerns basic content by subject: biography, history, geography, society, culture, science, technology, and mathematics.[W 54] It is not rare for articles strongly related to a particular language not to have counterparts in another edition. For example, articles about small towns in the United States might be available only in English, even when they meet the notability criteria of other language Wikipedia projects.[W 34]

Translated articles represent only a small portion of articles in most editions, in part because those editions do not allow fully automated translation of articles. Articles available in more than one language may offer "interwiki links", which link to the counterpart articles in other editions.[115][W 55]

A study published by PLOS One in 2012 also estimated the share of contributions to different editions of Wikipedia from different regions of the world. It reported that the proportion of the edits made from North America was 51% for the English Wikipedia, and 25% for the Simple English Wikipedia.[114]

English Wikipedia editor numbers

On March 1, 2014, The Economist, in an article titled "The Future of Wikipedia", cited a trend analysis concerning data published by the Wikimedia Foundation stating that "the number of editors for the English-language version has fallen by a third in seven years."[116] The attrition rate for active editors in English Wikipedia was cited by The Economist as substantially in contrast to statistics for Wikipedia in other languages (non-English Wikipedia). The Economist reported that the number of contributors with an average of five or more edits per month was relatively constant since 2008 for Wikipedia in other languages at approximately 42,000 editors within narrow seasonal variances of about 2,000 editors up or down. The number of active editors in English Wikipedia, by sharp comparison, was cited as peaking in 2007 at approximately 50,000 and dropping to 30,000 by the start of 2014.[116]

In contrast, the trend analysis for Wikipedia in other languages (non-English Wikipedia) shows success in retaining active editors on a renewable and sustained basis, with their numbers remaining relatively constant at approximately 42,000. No comment was made concerning which of the differentiated edit policy standards from Wikipedia in other languages (non-English Wikipedia) would provide a possible alternative to English Wikipedia for effectively improving substantial editor attrition rates on the English-language Wikipedia.[116]

Reception

Various Wikipedians have criticized Wikipedia's large and growing regulation, which includes more than fifty policies and nearly 150,000 words as of 2014.[update][117][91]

Critics have stated that Wikipedia exhibits systemic bias. In 2010, columnist and journalist Edwin Black described Wikipedia as being a mixture of "truth, half-truth, and some falsehoods".[118] Articles in The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Journal of Academic Librarianship have criticized Wikipedia's "Undue Weight" policy, concluding that Wikipedia explicitly is not designed to provide correct information about a subject, but rather focus on all the major viewpoints on the subject, give less attention to minor ones, and creates omissions that can lead to false beliefs based on incomplete information.[119][120][121]

Journalists Oliver Kamm and Edwin Black alleged (in 2010 and 2011 respectively) that articles are dominated by the loudest and most persistent voices, usually by a group with an "ax to grind" on the topic.[118][122] A 2008 article in Education Next Journal concluded that as a resource about controversial topics, Wikipedia is subject to manipulation and spin.[123]

In 2020, Omer Benjakob and Stephen Harrison noted that "Media coverage of Wikipedia has radically shifted over the past two decades: once cast as an intellectual frivolity, it is now lauded as the 'last bastion of shared reality' online."[124]

Multiple news networks and pundits have accused Wikipedia of being ideologically biased. In February 2021, Fox News accused Wikipedia of whitewashing communism and socialism and having too much "leftist bias".[125] Wikipedia co-founder Sanger said that Wikipedia has become a "propaganda" for the left-leaning "establishment" and warned the site can no longer be trusted.[126] In 2022, libertarian John Stossel opined that Wikipedia, a site he financially supported at one time, appeared to have gradually taken a significant turn in bias to the political left, specifically on political topics.[127] Some studies highlight the fact that Wikipedia (and in particular the English Wikipedia) has a "western cultural bias" (or "pro-western bias")[128] or "Eurocentric bias",[129] reiterating, says Anna Samoilenko, "similar biases that are found in the 'ivory tower' of academic historiography". Due to this persistent Eurocentrism, scholars like Carwil Bjork-James[130] or the authors of ''The colonization of Wikipedia: evidence from characteristic editing behaviors of warring camps''[131] call for a "decolonization" of Wikipedia.

Accuracy of content

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Articles for traditional encyclopedias such as Encyclopædia Britannica are written by experts, lending such encyclopedias a reputation for accuracy.[132] However, a peer review in 2005 of forty-two scientific entries on both Wikipedia and Encyclopædia Britannica by the science journal Nature found few differences in accuracy, and concluded that "the average science entry in Wikipedia contained around four inaccuracies; Britannica, about three."[133] Joseph Reagle suggested that while the study reflects "a topical strength of Wikipedia contributors" in science articles, "Wikipedia may not have fared so well using a random sampling of articles or on humanities subjects."[134] Others raised similar critiques.[135] The findings by Nature were disputed by Encyclopædia Britannica,[136][137] and in response, Nature gave a rebuttal of the points raised by Britannica.[138] In addition to the point-for-point disagreement between these two parties, others have examined the sample size and selection method used in the Nature effort, and suggested a "flawed study design" (in Nature's manual selection of articles, in part or in whole, for comparison), absence of statistical analysis (e.g., of reported confidence intervals), and a lack of study "statistical power" (i.e., owing to small sample size, 42 or 4 × 101 articles compared, vs >105 and >106 set sizes for Britannica and the English Wikipedia, respectively).[139]

As a consequence of the open structure, Wikipedia "makes no guarantee of validity" of its content, since no one is ultimately responsible for any claims appearing in it.[W 56] Concerns have been raised by PC World in 2009 regarding the lack of accountability that results from users' anonymity,[140][full citation needed] the insertion of false information,[141] vandalism, and similar problems.

Economist Tyler Cowen wrote: "If I had to guess whether Wikipedia or the median refereed journal article on economics was more likely to be true after a not so long think I would opt for Wikipedia." He comments that some traditional sources of non-fiction suffer from systemic biases, and novel results, in his opinion, are over-reported in journal articles as well as relevant information being omitted from news reports. However, he also cautions that errors are frequently found on Internet sites and that academics and experts must be vigilant in correcting them.[142] Amy Bruckman has argued that, due to the number of reviewers, "the content of a popular Wikipedia page is actually the most reliable form of information ever created".[143] In September 2022, The Sydney Morning Herald journalist Liam Mannix noted that, "There's no reason to expect Wikipedia to be accurate... And yet it [is]." Mannix further discussed the multiple studies that have proved Wikipedia to be generally as reliable as Encyclopedia Britannica, summarizing that, "...turning our back on such an extraordinary resource is... well, a little petty."[144]

Critics argue that Wikipedia's open nature and a lack of proper sources for most of the information makes it unreliable.[145] Some commentators suggest that Wikipedia may be reliable, but that the reliability of any given article is not clear.[146] Editors of traditional reference works such as the Encyclopædia Britannica have questioned the project's utility and status as an encyclopedia.[147] Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales has claimed that Wikipedia has largely avoided the problem of "fake news" because the Wikipedia community regularly debates the quality of sources in articles.[148]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Wikipedia's open structure inherently makes it an easy target for Internet trolls, spammers, and various forms of paid advocacy seen as counterproductive to the maintenance of a neutral and verifiable online encyclopedia.[68][W 57] In response to paid advocacy editing and undisclosed editing issues, Wikipedia was reported in an article in The Wall Street Journal to have strengthened its rules and laws against undisclosed editing.[150] The article stated that: "Beginning Monday [from the date of the article, June 16, 2014], changes in Wikipedia's terms of use will require anyone paid to edit articles to disclose that arrangement. Katherine Maher, the nonprofit Wikimedia Foundation's chief communications officer, said the changes address a sentiment among volunteer editors that, 'we're not an advertising service; we're an encyclopedia.'"[150][151][152][153][154] These issues, among others, had been parodied since the first decade of Wikipedia, notably by Stephen Colbert on The Colbert Report.[155]

Legal Research in a Nutshell (2011), cites Wikipedia as a "general source" that "can be a real boon" in "coming up to speed in the law governing a situation" and, "while not authoritative, can provide basic facts as well as leads to more in-depth resources".[156]

Discouragement in education

Some university lecturers discourage students from citing any encyclopedia in academic work, preferring primary sources;[157] some specifically prohibit Wikipedia citations.[158][159] Wales stresses that encyclopedias of any type are not usually appropriate to use as citable sources, and should not be relied upon as authoritative.[160] Wales once (2006 or earlier) said he receives about ten emails weekly from students saying they got failing grades on papers because they cited Wikipedia; he told the students they got what they deserved. "For God's sake, you're in college; don't cite the encyclopedia", he said.[161][162]

In February 2007, an article in The Harvard Crimson newspaper reported that a few of the professors at Harvard University were including Wikipedia articles in their syllabi, although without realizing the articles might change.[163] In June 2007, Michael Gorman, former president of the American Library Association, condemned Wikipedia, along with Google, stating that academics who endorse the use of Wikipedia are "the intellectual equivalent of a dietitian who recommends a steady diet of Big Macs with everything".[164]

A 2020 research study published in Studies in Higher Education argued that Wikipedia could be applied in the higher education "flipped classroom", an educational model where students learn before coming to class and apply it in classroom activities. The experimental group was instructed to learn before class and get immediate feedback before going in (the flipped classroom model), while the control group was given direct instructions in class (the conventional classroom model). The groups were then instructed to collaboratively develop Wikipedia entries, which would be graded in quality after the study. The results showed that the experimental group yielded more Wikipedia entries and received higher grades in quality. The study concluded that learning with Wikipedia in flipped classrooms was more effective than in conventional classrooms, demonstrating Wikipedia could be used as an educational tool in higher education.[165]

Medical information

On March 5, 2014, Julie Beck writing for The Atlantic magazine in an article titled "Doctors' #1 Source for Healthcare Information: Wikipedia", stated that "Fifty percent of physicians look up conditions on the (Wikipedia) site, and some are editing articles themselves to improve the quality of available information."[166] Beck continued to detail in this article new programs of Amin Azzam at the University of San Francisco to offer medical school courses to medical students for learning to edit and improve Wikipedia articles on health-related issues, as well as internal quality control programs within Wikipedia organized by James Heilman to improve a group of 200 health-related articles of central medical importance up to Wikipedia's highest standard of articles using its Featured Article and Good Article peer-review evaluation process.[166] In a May 7, 2014, follow-up article in The Atlantic titled "Can Wikipedia Ever Be a Definitive Medical Text?", Julie Beck quotes WikiProject Medicine's James Heilman as stating: "Just because a reference is peer-reviewed doesn't mean it's a high-quality reference."[167] Beck added that: "Wikipedia has its own peer review process before articles can be classified as 'good' or 'featured'. Heilman, who has participated in that process before, says 'less than one percent' of Wikipedia's medical articles have passed."[167]

Coverage of topics and systemic bias

This section needs to be updated. (June 2023) |

Wikipedia seeks to create a summary of all human knowledge in the form of an online encyclopedia, with each topic covered encyclopedically in one article. Since it has terabytes of disk space, it can have far more topics than can be covered by any printed encyclopedia.[W 58] The exact degree and manner of coverage on Wikipedia is under constant review by its editors, and disagreements are not uncommon (see deletionism and inclusionism).[168][169] Wikipedia contains materials that some people may find objectionable, offensive, or pornographic.[W 59] The "Wikipedia is not censored" policy has sometimes proved controversial: in 2008, Wikipedia rejected an online petition against the inclusion of images of Muhammad in the English edition of its Muhammad article, citing this policy.[170] The presence of politically, religiously, and pornographically sensitive materials in Wikipedia has led to the censorship of Wikipedia by national authorities in China[171] and Pakistan,[172] amongst other countries.[173][174][175]

Through its "Wikipedia Loves Libraries" program, Wikipedia has partnered with major public libraries such as the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts to expand its coverage of underrepresented subjects and articles.[176] A 2011 study conducted by researchers at the University of Minnesota indicated that male and female editors focus on different coverage topics. There was a greater concentration of females in the "people and arts" category, while males focus more on "geography and science".[177]

Coverage of topics and bias

Research conducted by Mark Graham of the Oxford Internet Institute in 2009 indicated that the geographic distribution of article topics is highly uneven, Africa being the most underrepresented.[178] Across 30 language editions of Wikipedia, historical articles and sections are generally Eurocentric and focused on recent events.[179]

An editorial in The Guardian in 2014 claimed that more effort went into providing references for a list of female porn actors than a list of women writers.[180] Data has also shown that Africa-related material often faces omission; a knowledge gap that a July 2018 Wikimedia conference in Cape Town sought to address.[111]

Systemic biases

Academic studies of Wikipedia have consistently shown that Wikipedia systematically over-represents a point of view (POV) belonging to a particular demographic described as the "average Wikipedian", who is an educated, technically inclined, English speaking white male, aged 15–49 from a developed Christian country in the northern hemisphere.[181] This POV is over-represented in relation to all existing POVs.[182][183] This systemic bias in editor demographic results in cultural bias, gender bias, and geographical bias on Wikipedia.[184][185] There are two broad types of bias, which are implicit (when a topic is omitted) and explicit (when a certain POV is over-represented in an article or by references).[182]

Interdisciplinary scholarly assessments of Wikipedia articles have found that while articles are typically accurate and free of misinformation, they are also typically incomplete and fail to present all perspectives with a neutral point of view.[184] In 2011, Wales claimed that the unevenness of coverage is a reflection of the demography of the editors, citing for example "biographies of famous women through history and issues surrounding early childcare".[37] The October 22, 2013, essay by Tom Simonite in MIT's Technology Review titled "The Decline of Wikipedia" discussed the effect of systemic bias and policy creep on the downward trend in the number of editors.[38]

Explicit content

Wikipedia has been criticized for allowing information about graphic content.[186] Articles depicting what some critics have called objectionable content (such as feces, cadaver, human penis, vulva, and nudity) contain graphic pictures and detailed information easily available to anyone with access to the internet, including children.[W 60]

The site also includes sexual content such as images and videos of masturbation and ejaculation, illustrations of zoophilia, and photos from hardcore pornographic films in its articles. It also has non-sexual photographs of nude children.[W 61]

The Wikipedia article about Virgin Killer—a 1976 album from the German rock band Scorpions—features a picture of the album's original cover, which depicts a naked prepubescent girl. The original release cover caused controversy and was replaced in some countries. In December 2008, access to the Wikipedia article Virgin Killer was blocked for four days by most Internet service providers in the United Kingdom after the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) decided the album cover was a potentially illegal indecent image and added the article's URL to a "blacklist" it supplies to British internet service providers.[187]

In April 2010, Sanger wrote a letter to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, outlining his concerns that two categories of images on Wikimedia Commons contained child pornography, and were in violation of US federal obscenity law.[188][189] Sanger later clarified that the images, which were related to pedophilia and one about lolicon, were not of real children, but said that they constituted "obscene visual representations of the sexual abuse of children", under the PROTECT Act of 2003.[190] That law bans photographic child pornography and cartoon images and drawings of children that are obscene under American law.[190] Sanger also expressed concerns about access to the images on Wikipedia in schools.[191] Wikimedia Foundation spokesman Jay Walsh strongly rejected Sanger's accusation,[192] saying that Wikipedia did not have "material we would deem to be illegal. If we did, we would remove it."[192] Following the complaint by Sanger, Wales deleted sexual images without consulting the community. After some editors who volunteered to maintain the site argued that the decision to delete had been made hastily, Wales voluntarily gave up some of the powers he had held up to that time as part of his co-founder status. He wrote in a message to the Wikimedia Foundation mailing-list that this action was "in the interest of encouraging this discussion to be about real philosophical/content issues, rather than be about me and how quickly I acted".[193] Critics, including Wikipediocracy, noticed that many of the pornographic images deleted from Wikipedia since 2010 have reappeared.[194]

Privacy

One privacy concern in the case of Wikipedia is the right of a private citizen to remain a "private citizen" rather than a "public figure" in the eyes of the law.[195][note 7] It is a battle between the right to be anonymous in cyberspace and the right to be anonymous in real life. The Wikimedia Foundation's privacy policy states, "we believe that you shouldn't have to provide personal information to participate in the free knowledge movement", and states that "personal information" may be shared "For legal reasons", "To Protect You, Ourselves & Others", or "To Understand & Experiment".[W 62]

In January 2006, a German court ordered the German Wikipedia shut down within Germany because it stated the full name of Boris Floricic, aka "Tron", a deceased hacker. On February 9, 2006, the injunction against Wikimedia Deutschland was overturned, with the court rejecting the notion that Tron's right to privacy or that of his parents was being violated.[196]

Wikipedia has a "Volunteer Response Team" that uses Znuny, a free and open-source software fork of OTRS[W 63] to handle queries without having to reveal the identities of the involved parties. This is used, for example, in confirming the permission for using individual images and other media in the project.[W 64]

In late April 2023, Wikimedia Foundation announced that Wikipedia will not submit to any age verifications that may be required by the Online Safety Bill. Rebecca MacKinnon of the Wikimedia Foundation said that such checks would run counter to the website's commitment to minimal data collection on its contributors and readers.[197]

Sexism

Wikipedia was described in 2015 as harboring a battleground culture of sexism and harassment.[198][199] The perceived tolerance of abusive language was a reason put forth in 2013 for the gender gap in Wikipedia editorship.[200] Edit-a-thons have been held to encourage female editors and increase the coverage of women's topics.[201]

In May 2018, a Wikipedia editor rejected a submitted article about Donna Strickland due to lack of coverage in the media.[W 65][202] Five months later, Strickland won a Nobel Prize in Physics "for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics", becoming the third woman to ever receive the award.[202][203] Prior to winning the award, Strickland's only mention on Wikipedia was in the article about her collaborator and co-winner of the award Gérard Mourou.[202] Her exclusion from Wikipedia led to accusations of sexism, but Corinne Purtill writing for Quartz argued that "it's also a pointed lesson in the hazards of gender bias in media, and of the broader consequences of underrepresentation."[204] Purtill attributes the issue to the gender bias in media coverage.[204]

A comprehensive 2008 survey, published in 2016, by Julia B. Bear of Stony Brook University's College of Business and Benjamin Collier of Carnegie Mellon University found significant gender differences in confidence in expertise, discomfort with editing, and response to critical feedback. "Women reported less confidence in their expertise, expressed greater discomfort with editing (which typically involves conflict), and reported more negative responses to critical feedback compared to men."[205]

Operation

Wikimedia Foundation and affiliate movements

Wikipedia is hosted and funded by the Wikimedia Foundation, a non-profit organization which also operates Wikipedia-related projects such as Wiktionary and Wikibooks.[W 66] The foundation relies on public contributions and grants to fund its mission.[206][W 67] The foundation's 2020 Internal Revenue Service Form 990 shows revenue of $124.6 million and expenses of almost $112.2 million, with assets of about $191.2 million and liabilities of almost $11 million.[W 68]

In May 2014, Wikimedia Foundation named Lila Tretikov as its second executive director, taking over for Sue Gardner.[W 69] The Wall Street Journal reported on May 1, 2014, that Tretikov's information technology background from her years at University of California offers Wikipedia an opportunity to develop in more concentrated directions guided by her often repeated position statement that, "Information, like air, wants to be free."[207][208] The same Wall Street Journal article reported these directions of development according to an interview with spokesman Jay Walsh of Wikimedia, who "said Tretikov would address that issue (paid advocacy) as a priority. 'We are really pushing toward more transparency ... We are reinforcing that paid advocacy is not welcome.' Initiatives to involve greater diversity of contributors, better mobile support of Wikipedia, new geo-location tools to find local content more easily, and more tools for users in the second and third world are also priorities", Walsh said.[207]

Following the departure of Tretikov from Wikipedia due to issues concerning the use of the "superprotection" feature which some language versions of Wikipedia have adopted,[W 70] Katherine Maher became the third executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation in June 2016.[W 71] Maher stated that one of her priorities would be the issue of editor harassment endemic to Wikipedia as identified by the Wikipedia board in December. She said to Bloomberg Businessweek regarding the harassment issue that: "It establishes a sense within the community that this is a priority ... [and that correction requires that] it has to be more than words."[110]

Maher served as executive director until April 2021.[209] Maryana Iskander was named the incoming CEO in September 2021, and took over that role in January 2022. She stated that one of her focuses would be increasing diversity in the Wikimedia community.[210]

Wikipedia is also supported by many organizations and groups that are affiliated with the Wikimedia Foundation but independently-run, called Wikimedia movement affiliates. These include Wikimedia chapters (which are national or sub-national organizations, such as Wikimedia Deutschland and Wikimedia France), thematic organizations (such as Amical Wikimedia for the Catalan language community), and user groups. These affiliates participate in the promotion, development, and funding of Wikipedia.[W 72]

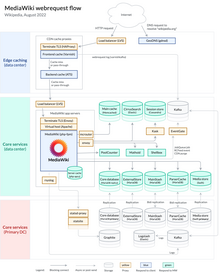

Software operations and support

The operation of Wikipedia depends on MediaWiki, a custom-made, free and open source wiki software platform written in PHP and built upon the MySQL database system.[W 73] The software incorporates programming features such as a macro language, variables, a transclusion system for templates, and URL redirection.[W 74] MediaWiki is licensed under the GNU General Public License (GPL) and it is used by all Wikimedia projects, as well as many other wiki projects.[W 73][W 75] Originally, Wikipedia ran on UseModWiki written in Perl by Clifford Adams (Phase I), which initially required CamelCase for article hyperlinks; the present double bracket style was incorporated later.[W 76] Starting in January 2002 (Phase II), Wikipedia began running on a PHP wiki engine with a MySQL database; this software was custom-made for Wikipedia by Magnus Manske. The Phase II software was repeatedly modified to accommodate the exponentially increasing demand. In July 2002 (Phase III), Wikipedia shifted to the third-generation software, MediaWiki, originally written by Lee Daniel Crocker.

Several MediaWiki extensions are installed to extend the functionality of the MediaWiki software.[W 77]

In April 2005, a Lucene extension[W 78][W 79] was added to MediaWiki's built-in search and Wikipedia switched from MySQL to Lucene for searching. Lucene was later replaced by CirrusSearch which is based on Elasticsearch.[W 80]

In July 2013, after extensive beta testing, a WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) extension, VisualEditor, was opened to public use.[211][212][213] It was met with much rejection and criticism, and was described as "slow and buggy".[214] The feature was changed from opt-out to opt-in afterward.[W 81]

Automated editing

Computer programs called bots have often been used to perform simple and repetitive tasks, such as correcting common misspellings and stylistic issues, or to start articles such as geography entries in a standard format from statistical data.[W 82][215][216] One controversial contributor, Sverker Johansson, created articles with his bot Lsjbot, which was reported to create up to 10,000 articles on the Swedish Wikipedia on certain days.[217] Additionally, there are bots designed to automatically notify editors when they make common editing errors (such as unmatched quotes or unmatched parentheses).[W 83] Edits falsely identified by bots as the work of a banned editor can be restored by other editors. An anti-vandal bot is programmed to detect and revert vandalism quickly.[215] Bots are able to indicate edits from particular accounts or IP address ranges, as occurred at the time of the shooting down of the MH17 jet in July 2014 when it was reported that edits were made via IPs controlled by the Russian government.[218] Bots on Wikipedia must be approved before activation.[W 84]

According to Andrew Lih, the current expansion of Wikipedia to millions of articles would be difficult to envision without the use of such bots.[219]

Hardware operations and support

As of 2021,[update] page requests are first passed to a front-end layer of Varnish caching servers and back-end layer caching is done by Apache Traffic Server.[W 85] Requests that cannot be served from the Varnish cache are sent to load-balancing servers running the Linux Virtual Server software, which in turn pass them to one of the Apache web servers for page rendering from the database.[W 85] The web servers deliver pages as requested, performing page rendering for all the language editions of Wikipedia. To increase speed further, rendered pages are cached in a distributed memory cache until invalidated, allowing page rendering to be skipped entirely for most common page accesses.[220]

Wikipedia currently runs on dedicated clusters of Linux servers running the Debian operating system.[W 86] As of February 2023,[update] caching clusters are located in Amsterdam, San Francisco, Singapore, and Marseille.[W 27][W 87] By January 22, 2013, Wikipedia had migrated its primary data center to an Equinix facility in Ashburn, Virginia.[W 88][221] In 2017, Wikipedia installed a caching cluster in an Equinix facility in Singapore, the first of its kind in Asia.[W 89] In 2022, a caching data center was opened in Marseille, France.[W 90]

Internal research and operational development

Following growing amounts of incoming donations in 2013 exceeding seven digits,[38] the Foundation has reached a threshold of assets which qualify its consideration under the principles of industrial organization economics to indicate the need for the re-investment of donations into the internal research and development of the Foundation.[222] Two projects of such internal research and development have been the creation of a Visual Editor and the "Thank" tab in the edit history, which were developed to improve issues of editor attrition.[38][214] The estimates for reinvestment by industrial organizations into internal research and development was studied by Adam Jaffe, who recorded that the range of 4% to 25% annually was to be recommended, with high-end technology requiring the higher level of support for internal reinvestment.[223] At the 2013 level of contributions for Wikimedia presently documented as 45 million dollars,[W 91] the computed budget level recommended by Jaffe for reinvestment into internal research and development is between 1.8 million and 11.3 million dollars annually.[223] In 2019, the level of contributions were reported by the Wikimedia Foundation as being at $120 million annually,[W 92] updating the Jaffe estimates for the higher level of support to between $3.08 million and $19.2 million annually.[223]

Internal news publications

Multiple Wikimedia projects have internal news publications. Wikimedia's online newspaper The Signpost was founded in 2005 by Michael Snow, a Wikipedia administrator who would join the Wikimedia Foundation's board of trustees in 2008.[224][225] The publication covers news and events from the English Wikipedia, the Wikimedia Foundation, and Wikipedia's sister projects.[W 93]

The Wikipedia Library

The Wikipedia Library is a resource for Wikipedia editors which provides free access to a wide range of digital publications, so that they can consult and cite these while editing the encyclopedia.[226][227] Over 60 publishers have partnered with The Wikipedia Library to provide access to their resources: when ICE Publishing joined in 2020, a spokesman said "By enabling free access to our content for Wikipedia editors, we hope to further the research community's resources – creating and updating Wikipedia entries on civil engineering which are read by thousands of monthly readers."[228]

Access to content

Content licensing

When the project was started in 2001, all text in Wikipedia was covered by the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL), a copyleft license permitting the redistribution, creation of derivative works, and commercial use of content while authors retain copyright of their work.[W 26] The GFDL was created for software manuals that come with free software programs licensed under the GPL. This made it a poor choice for a general reference work: for example, the GFDL requires the reprints of materials from Wikipedia to come with a full copy of the GFDL text.[229] In December 2002, the Creative Commons license was released; it was specifically designed for creative works in general, not just for software manuals. The Wikipedia project sought the switch to the Creative Commons.[W 94] Because the GFDL and Creative Commons were incompatible, in November 2008, following the request of the project, the Free Software Foundation (FSF) released a new version of the GFDL designed specifically to allow Wikipedia to relicense its content to CC BY-SA by August 1, 2009.[W 95] In April 2009, Wikipedia and its sister projects held a community-wide referendum which decided the switch in June 2009.[W 96][W 97][W 98][W 99]

The handling of media files (e.g. image files) varies across language editions. Some language editions, such as the English Wikipedia, include non-free image files under fair use doctrine,[W 100] while the others have opted not to, in part because of the lack of fair use doctrines in their home countries (e.g. in Japanese copyright law). Media files covered by free content licenses (e.g. Creative Commons' CC BY-SA) are shared across language editions via Wikimedia Commons repository, a project operated by the Wikimedia Foundation.[W 101] Wikipedia's accommodation of varying international copyright laws regarding images has led some to observe that its photographic coverage of topics lags behind the quality of the encyclopedic text.[230]

The Wikimedia Foundation is not a licensor of content on Wikipedia or its related projects but merely a hosting service for contributors to and licensors of Wikipedia, a position which was successfully defended in 2004 in a court in France.[231][232]

Methods of access

Because Wikipedia content is distributed under an open license, anyone can reuse or re-distribute it at no charge.[W 102] The content of Wikipedia has been published in many forms, both online and offline, outside the Wikipedia website.

Thousands of "mirror sites" exist that republish content from Wikipedia; two prominent ones that also include content from other reference sources are Reference.com and Answers.com.[233][234] Another example is Wapedia, which began to display Wikipedia content in a mobile-device-friendly format before Wikipedia itself did.[W 103] Some web search engines make special use of Wikipedia content when displaying search results: examples include Microsoft Bing (via technology gained from Powerset)[235] and DuckDuckGo.

Collections of Wikipedia articles have been published on optical discs. An English version released in 2006 contained about 2,000 articles.[W 104] The Polish-language version from 2006 contains nearly 240,000 articles,[W 105] the German-language version from 2007/2008 contains over 620,000 articles,[W 106] and the Spanish-language version from 2011 contains 886,000 articles.[W 107] Additionally, "Wikipedia for Schools", the Wikipedia series of CDs / DVDs produced by Wikipedia and SOS Children, is a free selection from Wikipedia designed for education towards children eight to seventeen.[W 108]

There have been efforts to put a select subset of Wikipedia's articles into printed book form.[236][W 109] Since 2009, tens of thousands of print-on-demand books that reproduced English, German, Russian, and French Wikipedia articles have been produced by the American company Books LLC and by three Mauritian subsidiaries of the German publisher VDM.[237]

The website DBpedia, begun in 2007, extracts data from the infoboxes and category declarations of the English-language Wikipedia.[238] Wikimedia has created the Wikidata project with a similar objective of storing the basic facts from each page of Wikipedia and other Wikimedia Foundation projects and make it available in a queryable semantic format, RDF.[W 110] As of February 2023,[update] it has over 101 million items.[W 111] WikiReader is a dedicated reader device that contains an offline copy of Wikipedia, which was launched by OpenMoko and first released in 2009.[W 112]

Obtaining the full contents of Wikipedia for reuse presents challenges, since direct cloning via a web crawler is discouraged.[W 113] Wikipedia publishes "dumps" of its contents, but these are text-only; as of 2023,[update] there is no dump available of Wikipedia's images.[W 114] Wikimedia Enterprise is a for-profit solution to this.[239]

Several languages of Wikipedia also maintain a reference desk, where volunteers answer questions from the general public. According to a study by Pnina Shachaf in the Journal of Documentation, the quality of the Wikipedia reference desk is comparable to a standard library reference desk, with an accuracy of 55 percent.[240]

Mobile access

Wikipedia's original medium was for users to read and edit content using any standard web browser through a fixed Internet connection. Although Wikipedia content has been accessible through the mobile web since July 2013, The New York Times on February 9, 2014, quoted Erik Möller, deputy director of the Wikimedia Foundation, stating that the transition of internet traffic from desktops to mobile devices was significant and a cause for concern and worry. The article in The New York Times reported the comparison statistics for mobile edits stating that, "Only 20 percent of the readership of the English-language Wikipedia comes via mobile devices, a figure substantially lower than the percentage of mobile traffic for other media sites, many of which approach 50 percent. And the shift to mobile editing has lagged even more." In 2014 The New York Times reported that Möller has assigned "a team of 10 software developers focused on mobile", out of a total of approximately 200 employees working at the Wikimedia Foundation. One principal concern cited by The New York Times for the "worry" is for Wikipedia to effectively address attrition issues with the number of editors which the online encyclopedia attracts to edit and maintain its content in a mobile access environment.[8] By 2023, the Wikimedia Foundation's staff had grown to over 700 employees.[7]

Bloomberg Businessweek reported in July 2014 that Google's Android mobile apps have dominated the largest share of global smartphone shipments for 2013, with 78.6% of market share over their next closest competitor in iOS with 15.2% of the market.[241] At the time of the appointment of new Wikimedia Foundation executive Lila Tretikov, Wikimedia representatives made a technical announcement concerning the number of mobile access systems in the market seeking access to Wikipedia. Soon after, the representatives stated that Wikimedia would be applying an all-inclusive approach to accommodate as many mobile access systems as possible in its efforts for expanding general mobile access, including BlackBerry and the Windows Phone system, making market share a secondary issue.[208] The Android app for Wikipedia was released on July 23, 2014, to over 500,000 installs and generally positive reviews, scoring over four of a possible five in a poll of approximately 200,000 users downloading from Google.[W 115][W 116] The version for iOS was released on April 3, 2013, to similar reviews.[W 117]

Access to Wikipedia from mobile phones was possible as early as 2004, through the Wireless Application Protocol (WAP), via the Wapedia service.[W 103] In June 2007, Wikipedia launched en.mobile.wikipedia.org, an official website for wireless devices. In 2009, a newer mobile service was officially released, located at en.m.wikipedia.org, which caters to more advanced mobile devices such as the iPhone, Android-based devices, or WebOS-based devices.[W 118] Several other methods of mobile access to Wikipedia have emerged since. Many devices and applications optimize or enhance the display of Wikipedia content for mobile devices, while some also incorporate additional features such as use of Wikipedia metadata like geoinformation.[242][243]

Wikipedia Zero was an initiative of the Wikimedia Foundation to expand the reach of the encyclopedia to the developing countries by partnering with mobile operators to allow free access.[W 119][244] It was discontinued in February 2018 due to lack of participation from mobile operators.[W 119]

Andrew Lih and Andrew Brown both maintain editing Wikipedia with smartphones is difficult and this discourages new potential contributors.[245][246] Lih states that the number of Wikipedia editors has been declining after several years,[245] and Tom Simonite of MIT Technology Review claims the bureaucratic structure and rules are a factor in this. Simonite alleges some Wikipedians use the labyrinthine rules and guidelines to dominate others and those editors have a vested interest in keeping the status quo.[38] Lih alleges there is a serious disagreement among existing contributors on how to resolve this. Lih fears for Wikipedia's long-term future while Brown fears problems with Wikipedia will remain and rival encyclopedias will not replace it.[245][246]

Chinese access

Access to Wikipedia has been blocked in mainland China since May 2015.[16][247][248] This was done after Wikipedia started to use HTTPS encryption, which made selective censorship more difficult.[249]

Copycats

Russians have developed clones called Runiversalis[250] and Ruwiki.[251] Iranians have created a new website called wikisa.org.[W 120]

Cultural influence

Trusted source to combat fake news

In 2017–18, after a barrage of false news reports, both Facebook and YouTube announced they would rely on Wikipedia to help their users evaluate reports and reject false news.[13][14] Noam Cohen, writing in The Washington Post states, "YouTube's reliance on Wikipedia to set the record straight builds on the thinking of another fact-challenged platform, the Facebook social network, which announced last year that Wikipedia would help its users root out 'fake news'."[14][252]

Readership

In February 2014, The New York Times reported that Wikipedia was ranked fifth globally among all websites, stating "With 18 billion page views and nearly 500 million unique visitors a month, ... Wikipedia trails just Yahoo, Facebook, Microsoft and Google, the largest with 1.2 billion unique visitors."[8] However, its ranking dropped to 13th globally by June 2020 due mostly to a rise in popularity of Chinese websites for online shopping.[253] The website has since recovered its ranking as of April 2022.[254]

In addition to logistic growth in the number of its articles,[W 121] Wikipedia has steadily gained status as a general reference website since its inception in 2001.[255] The number of readers of Wikipedia worldwide reached 365 million at the end of 2009.[W 122] The Pew Internet and American Life project found that one third of US Internet users consulted Wikipedia.[256] In 2011, Business Insider gave Wikipedia a valuation of $4 billion if it ran advertisements.[257]

According to "Wikipedia Readership Survey 2011", the average age of Wikipedia readers is 36, with a rough parity between genders. Almost half of Wikipedia readers visit the site more than five times a month, and a similar number of readers specifically look for Wikipedia in search engine results. About 47 percent of Wikipedia readers do not realize that Wikipedia is a non-profit organization.[W 123]

As of February 2023,[update] Wikipedia attracts around 2 billion unique devices monthly, with the English Wikipedia receiving 10 billion pageviews each month.[W 1]

COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Wikipedia's coverage of the pandemic and fight against misinformation received international media attention, and brought an increase in Wikipedia readership overall.[258][259][260][261] Noam Cohen wrote in Wired that Wikipedia's effort to combat misinformation related to the pandemic was different from other major websites, opining, "Unless Twitter, Facebook and the others can learn to address misinformation more effectively, Wikipedia will remain the last best place on the Internet."[259] In October 2020, the World Health Organization announced they were freely licensing its infographics and other materials on Wikimedia projects.[262] There were nearly 7,000 COVID-19 related Wikipedia articles across 188 different Wikipedias, as of November 2021.[update][263][264]

Cultural significance

Wikipedia's content has also been used in academic studies, books, conferences, and court cases.[W 124][265][266] The Parliament of Canada's website refers to Wikipedia's article on same-sex marriage in the "related links" section of its "further reading" list for the Civil Marriage Act.[267] The encyclopedia's assertions are increasingly used as a source by organizations such as the US federal courts and the World Intellectual Property Organization[268]—though mainly for supporting information rather than information decisive to a case.[269] Content appearing on Wikipedia has also been cited as a source and referenced in some US intelligence agency reports.[270] In December 2008, the scientific journal RNA Biology launched a new section for descriptions of families of RNA molecules and requires authors who contribute to the section to also submit a draft article on the RNA family for publication in Wikipedia.[271]

Wikipedia has also been used as a source in journalism,[272][273] often without attribution, and several reporters have been dismissed for plagiarizing from Wikipedia.[274][275][276][277]

In 2006, Time magazine recognized Wikipedia's participation (along with YouTube, Reddit, MySpace, and Facebook) in the rapid growth of online collaboration and interaction by millions of people worldwide.[278] On September 16, 2007, The Washington Post reported that Wikipedia had become a focal point in the 2008 US election campaign, saying: "Type a candidate's name into Google, and among the first results is a Wikipedia page, making those entries arguably as important as any ad in defining a candidate. Already, the presidential entries are being edited, dissected and debated countless times each day."[279] An October 2007 Reuters article, titled "Wikipedia page the latest status symbol", reported the recent phenomenon of how having a Wikipedia article vindicates one's notability.[280]

One of the first times Wikipedia was involved in a governmental affair was on September 28, 2007, when Italian politician Franco Grillini raised a parliamentary question with the minister of cultural resources and activities about the necessity of freedom of panorama. He said that the lack of such freedom forced Wikipedia, "the seventh most consulted website", to forbid all images of modern Italian buildings and art, and claimed this was hugely damaging to tourist revenues.[281]

A working group led by Peter Stone (formed as a part of the Stanford-based project One Hundred Year Study on Artificial Intelligence) in its report called Wikipedia "the best-known example of crowdsourcing ... that far exceeds traditionally-compiled information sources, such as encyclopedias and dictionaries, in scale and depth".[282][283]