User:Yogabear2020/sandbox3

{GOCE|user=Yogabear2020|date=March 23–29, 2024 } add two more "} }" to put within shell

Note for talk page[edit]

On the usage of "SPARS" vs. "SPARs"

As part of my recent GOCE edit, I tried to unify the usage/formatting of the term "SPARS" (and variants). Looking through the sources revealed a variety of usage, even within articles produced by one organization (such as the USCG online newsletter "My CG", searching for articles tagged "SPARs" or "Spar"). So I made some choices, based on USCG usage, and came up with my own 'standard'. In my edits, I have:

- used "SPARS" to mean 'the (USCG) Women's Reserve', hence singular and usually preceded by "the", as in "the SPARS was authorized"

- used "SPAR" as a noun modifier, as in "SPAR recruitment poster" meaning "Women's Reserve recruitment poster" (two noun modifiers in this case, one noun as subject), or in "SPAR personnel"

- used "SPARs" to refer to the 'female reservists', hence plural, as in "200 SPARs were sent to Alaska". (as can be found in more recent (after 1946) "My CG" articles, see link above)

- based on above (and USCG sources), used "SPAR" also to mean an individual reservist, as in "the first SPAR to be recruited was"

- also used "Spar"/"Spars" in some cases to mean 'individual reservists' when found in direct quotes, as from Three Years Behind the Mast (1946), per MOS principal of minimal change. (MOS:PMC) NOTE: Behind the Mast, and other sources, do use "Spars" to refer to the Women's Reserve as a whole; but the USCG usage of "SPARs" is more recent, more authoritative (if not always consistent)—and using all-caps for "the SPARS" was already the choice of article as I found it.

I know this may be splitting hairs: but it does help making other small edits (such as checking verb tense, or deciding whether "the" is needed before "SPARS"). This is me being pedantically transparent.

Notes on recent GOCE edit[edit]

I just finished doing a GOCE edit, per a request by ATPendright on the GOCE Request page. As part of this, I attempted to:

- vary the use of repeated terms, such as USCG/SPARS, or even U.S. Navy. (partly in response to editing comment by ATCuprum17)

- make the usage of "SPARS" more consistent. (see separate thread above)

- use "em-dash" whenever possible. (this style-choice was evident before I arrived)

- trim the lede, esp. to eliminate repetition of items discussed later.

- improve accuracy of description of LORAN (with the help of User:Cuprum17, thanks!). LORAN is not the focus of the article, but I hope we got it right.

- re-order some sections of text, to bring together pieces of the same topic/argument (and tried! to bring the refs along).

- update a few section headings, to be more like nouns & more specific to topic.

- attribute unattributed passages, or better incorporate; and made effort to verify direct or block quotes (some quotes marked "direct" included paraphrase, for example). I did my best to correct–incorporate quoted text. Some sections seemed to cut/paste from WP sources (such WAVES or Dorothy C. Stratton) or other sources (such as those from Three Years Behind the Mast), without clear attribution.

That's most of it. Thanks for your patience as this novice tried to finish the task.

On the subject of GAN[edit]

AT Pendright mentioned in GOCE Request for Copyedit (WP:GOCE/REQ) that this article might be put up for an A-class review (ACN); so I've noted a few sections that could perhaps use some attention (if someone wanted to), especially to add to the "story":

- In the section African American women : I added "Yeoman" to Olivia Hooker (found easily on her page). Could rank be added to the other Black service-women? (Even the previous section on Native American women gives the rank of each.) I could not find this information (quickly) myself. (NOTE: some NPS articles refer to a "lack of records" on this issue of SPAR 'minority recruitment'—both for Black women, but also Hispanic, etc.

- Perhaps a few other details could be added for notable women in Minority recruitment? There is much notable about Olivia Hooker; and the NPS project on SPARS ( at the NPS article on SPARS, see end-links to other articles in the series), which has separate articles for each of the Native American recruits. (Yes, too many details would probably be more appropriate for individual articles; but a few might help in the section.)

- Consider adding another section ("Other"?) in Minority recruitment with some mention other diverse groups, such as Latina? I don't see that there was an "official" policy on this, but it is of interest, just to list "firsts" or other notable women. Again, "My CG" (articles related to SPARs) and NPS (linked above) both have specific articles on "minority" women. [I might try adding something about this myself, but not today.]

- In the section Women of the SPARS, could some examples be given, of actual awards? (One might search the USCG the USCG 1946 report (linked above), as it includes many lists, including in the captions of photos. Again, the USCG online newsletter "My CG" (linked above) is another good source, searching for articles tagged "SPARS" and/or "SPAR".

- As for adding to the "story", the LORAN article at "My CG" pulls out some VERY interesting stories about the "top-secret" aspect. (They all seem to come from Behind the Mast, but the "My CG" version is easier to read.)

That's my two-cents.

An alert to those who are following SPARS (perhaps Cuprum17, Pendright, and Jonesey95): I am currently attempting to do a GOCE copyedit for the March drive. As a novice, I may go a bit slowly; but I will try to finish by the end of the week. I did place a {GOCE in use} tag on the article. I'll be sure to post a note, and remove the tag, when I'm finished

I have noted a few issues that I will try to address; but someone more knowledgeable than me will certainly want to double-check.

- A very minor issue, but dashes were not uniform: I have tried to introduce em-dashes as much as possible, following the style mostly already in use; and to check for en-dashes (like in date ranges or in double-categories like "Yuchi–Choctaw")

- Cuprum17 noted in an edit comment that there is an over-use of USCG—but this applies to many of the acronyms and other uses, that could have more variety (like U.S. Congress vs just Congress). It might be good to include, as Cuprum17 does in one edit, more use of "Coast Guard" for USCG, as well as words like "reservists" or "the Reserve", to break up the repetition of SPARS.

- I have tried to pay attention to the use/formatting of SPARS. After comparing some of the sources, I've found a variety of formatting. The original 1946 report from the USCG uses "the SPARS" sparingly, mostly for the organization (e.g. to mean "the Women's Reserve") and in the ALL CAPS HEADINGS; but the USCG report frequently uses "Spar"/"Spars", for both the individual "reservist/s", and (seemingly) for the Reserve itself (all the women) (as "a policy regarding Spars" no "the"). The behind the scenes Three Years Behind the Mast uses "Spar"/"Spars" almost exclusively. (And, hence, the block quotes do the same, as in the quote from Commodore Hirshfield featured at the end of the article.) The "oral history" by Stratton (written much later than both) shows the use of "SPARs' " (as in "the SPARs' uniform "), and "SPAR" (in ref. to the coining the acronym); the title of the piece is "SPARs" (lowercase final 's') to mean "all the women in the Reserve" or "the Women's Reserve". In the articles by the National Park Service, the choice seems to vary, based on the source for (or writer of?) each specific article. They sometimes use "SPAR" as a modifier (like "SPAR personnel" or "SPAR recruiting poster") or for an individual reservist ("she enlisted as a SPAR"). In other cases, the NPS uses "Spar" (especially if a main source is Behind the Mast. So . . . I made some decisions in my editing, based on this, I edited with the use of:

- – "the SPARS" to mean "the Women's Reserve", a singular collective noun, almost always preceded by "the" (as it just seemed right, given SPAR, WAVES, WAC, etc.)

- – "Spar" only in direct quotations, to meet the "principal of minimal change" MOS:PMC

- – "SPAR" as noun modifier ("a SPAR policy", "SPAR recruiting poster")

- – "SPAR" or "SPARs" to refer to individual reservists ("to recruit more SPARs", "the first SPAR to enlist"), because this seemed to be in line with the style conventions already set by the article as I encountered it; although most sources use "Spar" or "Spars" to refer to "reservist/s". This is suggested by the Stratton's use (or the editor); and some of the use at NPS. (And is does seem to fit with the similar use of "WACs".)

I know this is splitting hairs; but I needed a specific rule of thumb, to copyedit the other issues (like singular noun/verb, which is not readily apparent with SPARS = sing. noun).

- I have attributed many unattributed quotes, and attempted to verify direct or block quotes (as some quote marked as "direct" included paraphrase). I did my best to correct or incorporate the quoted text. There were many sections that seemed to cut/paste from other sources (like the WP articles on WAVES or Dorothy C. Stratton) or the various USCG/NPS sources (especially the oral history on SPARS by Stratton, and the Behind the Mast history), without attribution.

Thanks for your patience as a novice made his way through this enjoyable piece of history. Feel free to respond, but I'll let you know when I've called it a day.

LEDE[edit]

SPARS was the authorized nickname for the United States Coast Guard (USCG) Women's Reserve. The nickname was an acronym fashioned from the USCG's motto, "Semper Paratus—Always Ready" (SPAR). (The female reservists themselves were sometimes referred to as "Spars" or, below, as SPARs.) The Women's Reserve was established by the U.S. Congress in late 1942 and signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on November 23.

LORAN

This newly developed and top-secret radio navigation system allowed stations in the continental U.S. to assist in position location, and navigation, for ships at sea and long-range aircraft.

NEW SHORT

This newly developed and top-secret radio navigation system allowed LORAN stations to assist ships and aircraft in finding their navigation location.

NEW LONG

This newly developed and top-secret radio navigation system allowed on-shore LORAN-equipped stations to assist ships and aircraft in finding their navigation location.

p117 (all-female manned stations) Loran Monitor Stations within the continental U.S. (manned by Spars) "transmitting station"

radio signals, transmitted from two shore-based stations, are picked up by a receiver-indicator installed in ships and planes, enabling them to calculate their exact position.

first Spar monitor station in Chatham

Women of the SPARS[edit]

Source for Three Years Behind the Mast (clickable) (Available online at: "The Story of The United States Coast Guard SPARS" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-03-28.)

Entered text below, but need to verify revised refs[edit]

As the authors of Three Years Behind the Mast describe, the average "Spar" officer would have been 29 years old, single, and a college graduate. She had worked seven years in a professional or managerial position (typically in education or government) before entering the service. The average enlisted member was in generally younger (24 years old), single, a high school graduate, and had worked for more than three years in a clerical or sales position before recruitment. In most cases, enlisted "Spars" likely came from the Northeastern states of Massachusetts, New York, or Pennsylvania; from the Midwestern Illinois and Ohio; or from the west-coast state of California.[1]

In their off-duty hours, SPARs contributed time and effort to many community and wartime causes. Some became active nurse's aides or rolled bandages for the Red Cross; others donated blood to blood banks; some visited service men in convalescent hospitals; and others collected gifts for the men overseas. Many of them were also involved in the March of Dimes campaigns, and war chest or war bond drives.[2] Based on their service, both officers and enlisted were awarded service ribbons and medals; and some were acknowledged for their outstanding contributions to the Women's Reserve and the country.[3]

THIS IS TOO GENERAL TO BE VERIFIED: needs to be a quote to show opinion In general, SPARs looked upon their service favorably, and many of them found a form of kinship in having been a part of the nation's military forces during wartime.

NEED TO ADD THIS and re-check page citations above, below[edit]

In reporting on their own personal experience as SPARs, the authors of Three Years Behind the Mast evaluate the overall positive experience had by many who served in the Women's Reserve, describing a sense of kinship that developed between them. Written at the end of the war (just after the demobilization of the Reserve), their "history of the Spars" relates the value of their service in this way: "We were taking away many intangible things that should be of value to us for the rest of our lives—increased tolerance, a new sense of self-confidence, a better idea of how to live and work with all kinds of people, [and} a keener recognition of our responsibility as world citizens."[4]

pg Behind the Mast, theon their service—and the sense of kinship they found with other service-women—

TO FIX (completed)[edit]

The standard Mainbocher-designed uniform was made of navy-blue wool and consisted of a single-breasted jacket, worn with a six-gored skirt, along with a white shirt and dark blue tie. Matching accessories included: black oxfords or plain black pumps; a brimmed hat; black gloves; a black leather purse; and both rain and winter coats. The summer uniform was similar to the standard, but made of white Palm Beach cloth, tropical worsted, or other light-weight fabrics; the shoes were white leather oxfords or pumps. Work wear for summer consisted of a grey-and-white striped seersucker dress and jacket.

Following the surrender of Japan in August 1945, the USCG demobilization effort began. SPAR personnel were gradually discharged; and, as with other U.S. service members, they were separated from the service on a point system or on the basis of their jobs. To aid in the process, many SPARs were reassigned to Coast Guard personnel separation centers, where they assisted in the demobilization of both male and female reservists. These reassigned reservists were later separated when demobilization was considered complete. By the middle of 1946, nearly all USCG female reservists had been discharged; and, with the end of World War II, the Coast Guard once again became part of the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

The Women's Reserve (SPARS) was inactivated on July 25, 1947, but later reactivated as the USCG Women's Volunteer Reserve on November 1, 1949, the eve of the Korean War. During the Korean conflict (1950-1953), the Coast Guard actively recruited former SPARs—both officers and enlisted personnel—for the volunteer reserve. Enlistment was for a three-year period. Approximately 200 former SPARs entered the Women's Volunteer Reserve and served during the Korean War. By 1968, about 158 women remained as active volunteer reservists. In 1973, Congress enacted legislation ending the Women's Volunteer Reserve, allowing women to be officially integrated into active-duty or the reserve. Following the policy change, those enlisted female reservists then serving on active duty were given the choice of enlisting in the regular USCG or completing their reserve enlistments.

Assignments (quote)[edit]

Most of the officers served in administrative and supervisory roles in various divisions of the USCG. Others served as communication officers, supply officers, and barracks and recruiting officers. The bulk of the enlisted women had clerical and stenographic civilian backgrounds—and the Coast Guard put them to work using these much-needed skills. As the authors of Three Years Behind the Mast explain, exciting jobs for most could be 'few and far between'. Yet they add that not all SPARs assigned to paperwork found it "boring". Even though some jobs were "humble, humdrum duties", as the authors put it, the women nevertheless could see how their contributions "fit into the overall picture". Though the majority of enlisted women worked in clerical positions—with many of them earning petty officer ratings as yeoman and storekeepers—enlisted personnel were found in nearly every job classification. As the Behind the Mast authors describe, they did everything from "baking pies to rigging parachutes and driving jeeps". MOS:INOROUT

A select group of officers and enlisted SPARs were chosen to work with LORAN (short for 'Long-Range Aid to Navigation'). This newly developed and top-secret radio navigation system allowed stations in the continental U.S. to monitor ships at sea and calculate the positions of long-range aircraft. In order to qualify for work at LORAN stations, reservists had to complete two months of instruction at M.I.T., focused on the operation and maintenance of the new system. The first monitoring station staffed by the SPARS was at Chatham, Massachusetts. The SPAR unit at Chatham was believed to have been (at the time) the only all-female staffed monitoring station of its kind in the world.

Female reservists were initially prohibited, by law, from serving in USCG districts outside the continental United States. But in late 1944, as the war was nearing an end, Congress lifted the prohibition; and this allowed SPARs to serve overseas. For those who had the right qualifications, were in good health, and had at least a year of service, the new authorization meant they could now request a transfer to Hawaii and Alaska (then U.S. territories). Before its inactivation in 1946, the Coast Guard sent about 200 women to serve in Hawaii, and another 200 to Alaska, where they performed roughly the same kind of work (and held the same ratings) as at the mainland stations.

Officer training DONE ready to go[edit]

The initial agreement between the Navy and the Coast Guard required that SPAR officer candidates receive their indoctrination at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts—the official Naval Reserve (WR) Midshipmen's School. But in June 1943, the USCG withdrew from the agreement; and the indoctrination for their Women's Reserve candidates was transferred to the USCG Academy in New London, Connecticut. Approximately 203 SPARs were enrolled at the New London Midshipmen's School (for the Women's Reserve); and the U.S. Coast Guard became the only U.S. military service to train female officer candidates at its own academy. [is this correct? is "female" needed?]

The officer training period was initially six weeks, but later increased to eight weeks. The program was designed to provide candidates with an overall view of the Coast Guard, and to help them become good officers. Academically, the curriculum included subjects such as: administration, correspondence, communications, history, organization, ships, personnel, and public speaking. Military regimentation, another part of training, was designed to help candidates adjust to military life and their responsibilities as officers. Candidates included women who, in their civilian life, had previously been employed as teachers, journalists, lawyers, and technicians. Approximately one-third of all officers received specialized training, either as communication officers or as pay and supply officers. To minimize the need (and time required) for extra instruction, the USCG intentionally recruited candidates whose previous civilian work experience would eliminate the need for further training.

By the end of the program, a total of 955 women—ranging in age from 24 to 40—had been commissioned and trained. Of these, 299 came up from the enlisted ranks. In late 1944, after determining that the number of commissioned officers was sufficient, the Coast Guard discontinued the program. However, when the need arose to replace officers who had been sent overseas or separated from the service, the training program was later reopened. The final class of officer candidates was made up of former enlisted SPARs who had trained at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York. (dates for this class? could be added)

DONE and revised again a second time and third re-read

Enlisted training[edit]

The agreement between the Navy and the Coast Guard also required that the USCG's enlisted recruits would receive their basic training at U.S. Naval Training Schools located around the country. About 1,900 SPARs received their recruit training at Hunter College in the Bronx, New York. A small number of SPARs received yeoman training at Oklahoma A&M University in Stillwater, Oklahoma. An additional 150 received yeoman training at Iowa State Teachers College in Cedar Falls, Iowa. But by March 1943, the USCG had decided to establish its own training center, both for basic and for specialized recruit training programs. They leased the Palm Beach Biltmore Hotel in Palm Beach, Florida; and the site was commissioned as a training station on May 23, 1943. Beginning in late June, all enlisted personnel began receiving both basic and specialized training at the new site.

The training period for recruits at Palm Beach was six weeks. Boot camp was designed to bridge the gap from civilian to military life. The training covered instruction on subjects such as: USCG activities and organization; personnel; and current events. [social hygiene? just hygiene, physical?] The physical component included education in body mechanics, swimming, games, and drill exercises.

Another important aspect of recruit training was the testing, classification, and selection process. This was designed to make the most of each recruit's abilities, background, and interests. Testing results provided a basis for general assignments, and the opportunity for further specialized training. Approximately 70 percent of enlisted women (mostly yeoman and storekeepers) received some specialized training. Some recruits attended different Navy schools to be trained as: motion picture sound technicians; link trainer operators; parachute riggers; or air control operators. Others attended USCG schools to be trained as cooks and bakers, but also as radioman, pharmacist mates, radio technicians, and motor vehicle drivers.

From the first class (June 14, 1943) to the final class (December 16, 1944), more than 7,000 recruits were trained at the Palm Beach station. In January 1945, the training of enlisted personnel was transferred from Palm Beach to Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn, New York, the largest USCG training station for men.

READY TO GO

The Spars asked no favors and no privileges. They, like most Americans, knew there was a job to be done and they went to work. The amazement of some of their hardbitten superiors is legendary. With enthusiasm, with efficiency, and with a minimum of fanfare, these young women began to take over. [...] The Service was fortunate in having the help of the [more than] 10,000 Spars who volunteered for duty in the Coast Guard when their country needed them, and carried the job through to a successful finish.

FIXED THIS - READY TO PASTE

As with the Navy WAVES, the Coast Guard did not officially open its doors to African American women until October 1944. This policy reflected the attitudes of the Secretary of the U.S. Navy, Frank Knox, who had become the supervisor of the USCG when it was made part of the Navy in November 1941. Knox vehemently opposed to the acceptance of African American women into the naval services. When Knox died in April 1944, he was replaced by James Forrestal. The new secretary recommended that African American women be accepted, but only under some desegregated conditions. President Roosevelt, as commander-in-chief, decided to delay any decision on the matter until after the 1944 United States presidential election (which would take place on November 7). In the interim, Roosevelt himself was criticized for discriminating against African American women—a critique made by the Republican presidential candidate, Thomas E. Dewey, during a speech in Chicago. In response, the president then reversed his earlier decision. On October 19, 1944, he ordered the Navy—and thereby the Coast Guard—to accept African American women into their women's reserves.

In 1945, five African American woman were accepted as SPARs and completed boot camp at the Brooklyn training center. The first enlisted was Olivia Hooker—becoming the first Black woman to enter the U.S. Coast Guard Reserves—accompanied by four others (who all attended the same boot camp). These four were: D. Winifred Byrd, Julia Mosley, Yvonne Cumberbatch, and Aileen Cooke. All five women were qualified for active duty during the latter part of the war, before the Women's Reserve was inactivated in 1947. WEB CITE (from gov site)

General[edit]

READY TO ENTER INTO THE ARTICLE

Early on in the planning process, both the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, along with the USCG, agreed to recruit and train their respective women's reserves together at existing Navy facilities.[5] For recruiting purposes, the SPARS would utilize the Office of Naval Officer Procurement. Their recruiting efforts began in December 1942, but were hampered at first by the lack of SPAR personnel. After the Navy agreed to allow transfer requests for its WAVES reservists, a total of 15 officers and 153 enlisted women discharged from the Navy reserves, becoming the first SPARS. Eventually, SPAR officers were assigned to most Naval Officer Procurement sites to facilitate USCG recruitment. Recruitment information about SPARS was sometimes disseminated along with WAVES publicity materials; but it became increasingly apparent that the job of selling the USCG Women's Reserves would include selling the U.S. Coast Guard itself.[6]

By June 1943, it was clear that combined SPARS-WAVES recruitment did not favor the Coast Guard itself, so it withdrew from the joint agreement effective July 1. After this point, all USCG applicants would be interviewed and enlisted only at USCG district recruiting stations. The change was met with enthusiasm by SPAR recruiters and yielded positive results overall.[7] But despite this change, competition with the other, better-known women's reserves remained keen. In Three Years Behind the Mast, written by former Women's Reserve officers Lyne and Arthur, the authors describe some of the difficulties faced by SPAR recruiters:

During the day, we made speeches, distributed posters, decorated windows, led parades, manned information booths, interviewed applicants, appeared on radio programs, and gave aptitude tests. By night, we made more speeches, prayed women would be drafted, and went to bed dreaming about our quotas.[8]

The primary recruitment phase ended on December 31, 1944. During the two-year effort, over 11,000 women signed enlistment contracts to join the Women's Reserve, though many more women were interviewed.[9] Of those applicants who otherwise met the requirements, one-fourth were rejected for failure to pass the medical exam.[10] In her 1989 oral history article, "Launching the SPARS", Dorothy C. Stratton revisited the recruiting practices during her tenure as director:

At first we were going for perfection in our recruiting effort. As we were falling behind in our numbers, modifications to physical requirements were made. It was ridiculous to make the same physical demands of women when they weren't going to be manning ships at sea. If we hadn't been so inflexible in our standards at the beginning—if we'd set more reasonable ones—I'm sure we'd have been better off.[11]

Dorothy Tuttle had the distinction of being the first woman to enlist in the Coast Guard Women's Reserve, on December 7, 1942. As a newly enlisted SPAR, her rating classification was that of a Yeoman Third Class (YN3).[12]

OK, CHECKED TO HERE

From Lede (entered into real article, with some small word changes, so not the same as below)

At peak strength, the Women's Reserve had approximately 11,000 officers and enlisted personnel.

Following the end of World War II in August 1945, the demobilization of SPARs personnel began. By 1946, nearly all reservists had been discharged; and in 1947, the Women's Reserve was officially inactivated. But on the eve of the Korean War in November 1949, the Women's Reserve was reactivated—this time as the USCG Women's Volunteer Reserve. Throughout the conflict in Korea (1950–1953), the USCG actively recruited former SPARs for the volunteer reserve, recruiting approximately 200 former reservists to return.

In 1973, Congress enacted legislation ending the Women's Volunteer Reserve, and allowing women to be officially integrated into either active-duty or reserve service.

blahblahblahblahblah "Semper Paratus—Always Ready"

blahblahblahblahblah "Semper ParatusAlways Ready"

blahblahblahblahblah "Semper Paratus—Always Ready"

The USCG has named two Coast Guard cutters in honor of the SPARS. USCGC Spar (WLB-403) was a 180-foot (55 m) sea going buoy tender that was commissioned on June 12, 1944. She had a complement of six officers and 74 enlisted in 1945; and later, in 1966, a complement of four officers, two warrant officers, and 47 enlisted. The cutter was decommissioned on February 28, 1997. The second vessel was USCGC Spar (WLB-206)—a 225-foot (69 m) seagoing buoy tender that was commissioned on August 3, 2001. As of the spring of 2022, she was still in active service, with a complement of eight officers and 40 enlisted.

Native American[edit]

As early as April 1943, an active effort was made by the SPARS to recruit Native American women. During World War II, no less than six women from Oklahoma's tribal nations enlisted as SPARs. This group included women from the Otoe-Missouria, Choctaw, Yuchi, and Cherokee tribal nations. Nicknamed the Sooner Squadron (since Oklahoma is known as "the Sooner State"), these six women included: Seaman Mildred Cleghorn Womack (Otoe), Yeoman Corrine Koshiway Goslin (Otoe), Yeoman Lula Mae O'Bannon (Choctaw), Yeoman Lula Belle Everidge (Choctaw), June Townsend (Yuchi–Choctaw), and Yeoman Nellie Locust (Cherokee). All six were enlisted personnel.[13]

The new director's first official act was to ask Mildred H. McAfee, director of the WAVES, for a core number of WAVE officers to help make Stratton's new USCG program operational. McAfee obliged. The next question on Stratton's mind was what to call the new women's service. In her 1989 oral history article, "Launching the SPARS", Stratton described her inspiration in selecting a name:

There was no one else to think about this ... so I tossed and turned for several nights contemplating this ... Suddenly it came to me from the motto of the Coast Guard, "Semper Paratus"–"Always Ready": SPAR. I proposed this to the Commandant of the USCG, Admiral Russell R. Waesche, and he accepted it.[11]

There had also been an informal proposal to call the new women's reserve "WARCOGS", but it was quickly jettisoned for the more nautical nickname of "SPARS".[14] Stratton also noted that the four letters (SPAR) might also stand for the four freedoms—of speech, of the press, of assembly, and of religion.

That same month Dorothy C. Stratton was appointed director of the SPARS and given the rank of lieutenant commander; she was later promoted to captain.

Notes for Owl's Eye Appearance[edit]

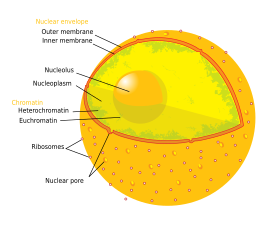

Parts of the Cell[edit]

Nucleus (see image)

Histopathology from Vacuole

In histopathology, vacuolization is the formation of vacuoles or vacuole-like structures, within or adjacent to cells. It is an unspecific sign of disease.

- ^ Lyne & Arthur 1946, pp. 103.

- ^ Lyne & Arthur 1946, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Lyne & Arthur 1946, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Lyne & Arthur 1946, pp. Foreward, 101.

- ^ Johnson 1987, pp. 198–199.

- ^ USCG At War-Women's Reserve 1946, p. 13-15.

- ^ USCG At War-Women's Reserve 1946, p. 21.

- ^ Lyne & Arthur 1946, p. 18.

- ^ USCG At War-Women's Reserve 1946, p. 51.

- ^ USCG At War-Women's Reserve 1946, p. 57.

- ^ a b Stratton 1989.

- ^ Moments in History 2023.

- ^ The Long Blue Line: "Sooner Squadron" SPARS Stories History Program - 2021 |https://www.mycg.uscg.mil/News/Article/2826944/the-long-blue-line-sooner-squadronfirst-native-american-women-to-enlist-in-the/

- ^ Tilley.