User:Pseudo-Richard/Economic history of Christianity

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

Christian views of wealth and materialism[edit]

According to Jack Mahoney, there are a variety of Christian attidues towards materialism and wealth. Mahoney characterizes the saying of Jesus in Mark 10:23-7 as having "imprinted themselves so deeplyon the Christian community through the centuries that those who are well off, or even comfortably off, often feel uneasy and troubled in conscience."[1]

John Cobb, Jr. argues that the "economism that rules the West and through it much of the East" is directly opposed to traditional Christian doctrine. Cobb invokes the teaching of Jesus that "man cannot serve both God and Mammon (wealth)". He asserts that it is obvious that "Western society is organized in the service of wealth" and thus wealth has triumphed over God in the West.[2]

Prosperity theology[edit]

Prosperity theology is a Christian religious belief whose proponents claim has "tens of millions"[3] of adherents, primarily in the United States, centered on the notion that God provides material prosperity for those he favors.[4] It has been defined by the belief that "Jesus blesses believers with riches"[3] or more specifically as the teaching that "believers have a right to the blessings of health and wealth and that they can obtain these blessings through positive confessions of faith and the 'sowing of seeds' through the faithful payments of tithes and offerings."[5] In the words of journalist Hanna Rosin, the prosperity gospel "is not a clearly defined denomination, but a strain of belief that runs through the Pentecostal Church and a surprising number of mainstream evangelical churches, with varying degrees of intensity."[3][4] It arose in the United States after World War II championed by Oral Roberts and became particularly popular in the decade of the 1990s.[3] More recently, the theology has been exported to less prosperous areas of the world, with mixed results.[6]

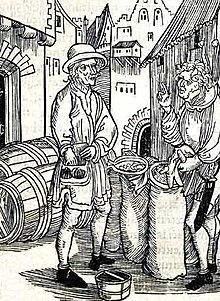

Usury[edit]

Usury originally was the charging of interest on loans; this included charging a fee for the use of money, such as at a bureau de change. In places where interest became acceptable, usury was interest above the rate allowed by law. Today, usury commonly is the charging of unreasonable or relatively high rates of interest. The term is largely derived from Christian religious principles;Riba is the corresponding Arabic term and ribbit is the Hebrew word.

The pivotal change in the English-speaking world seems to have come with the permission to charge interest on lent money: particularly the 1545 act "An Acte Agaynst Usurie" (37 H.viii 9) of King Henry VIII of England.

Theological debate[edit]

The first of the scholastics, Saint Anselm of Canterbury, led the shift in thought that labeled charging interest the same as theft. Previously usury had been seen as a lack of charity.

St. Thomas Aquinas, the leading theologian of the Catholic Church, argued charging of interest is wrong because it amounts to "double charging", charging for both the thing and the use of the thing.

This did not, as some think, prevent investment. What it stipulated was that in order for the investor to share in the profit he must share the risk. In short he must be a joint-venturer. Simply to invest the money and expect it to be returned regardless of the success of the venture was to make money simply by having money and not by taking any risk or by doing any work or by any effort or sacrifice at all. This is usury. St Thomas quotes Aristotle as saying that "to live by usury is exceedingly unnatural". St Thomas allows, however, charges for actual services provided. Thus a banker or credit-lender could charge for such actual work or effort as he did carry out e.g. any fair administrative charges.

In the 13th century Cardinal Hostiensis enumerated thirteen situations in which charging interest was not immoral.[7] The most important of these was lucrum cessans (profits given up) which allowed for the lender to charge interest "to compensate him for profit foregone in investing the money himself." (Rothbard 1995, p. 46) This idea is very similar to Opportunity Cost. Many scholastic thinkers who argued for a ban on interest charges also argued for the legitimacy of lucrum cessans profits (e.g.Pierre Jean Olivi and St. Bernardino of Siena).

One school of thought attributes Calvinism with setting the stage for the later development of capitalism in northern Europe. In this view, elements of Calvinism represented a revolt against the medieval condemnation of usury and, implicitly, of profit in general.[citation needed] Such a connection was advanced in influential works by R. H. Tawney (1880–1962) and by Max Weber (1864–1920).

Calvin expressed himself on usury in a 1545 letter to a friend, Claude de Sachin, in which he criticized the use of certain passages of scripture invoked by people opposed to the charging of interest. He reinterpreted some of these passages, and suggested that others of them had been rendered irrelevant by changed conditions. He also dismissed the argument (based upon the writings of Aristotle) that it is wrong to charge interest for money because money itself is barren. He said that the walls and the roof of a house are barren, too, but it is permissible to charge someone for allowing him to use them. In the same way, money can be made fruitful.[8]

He qualified his view, however, by saying that money should be lent to people in dire need without hope of interest, while a modest interest rate of 5% should be permitted in relation to other borrowers.[9]

Slavery[edit]

Slavery in different forms existed within Christianity for over 18 centuries. In the early years of Christianity, slavery was a normal feature of the economy and society in the Roman Empire, and this remained well into the Middle Ages and beyond.[10] Most Christian figures in that early period, such as Augustine of Hippo, supported continuing slavery whereas several figures such as Saint Patrick were opposed. Centuries later, as the abolition movement took shape across the globe, groups who advocated slavery's abolition worked to harness Christian teachings in support of their positions, using both the 'spirit of Christianity', biblical verses against slavery, and textual argumentation.[11]

The issue of Christianity and slavery is one that has seen intense conflict. While Christian abolitionists were a principal force in the abolition of slavery, the Bible sanctioned the use of regulated slavery in the Old Testament and whether or not theNew Testament condemned or sanctioned slavery has been strongly disputed. Passages in the Bible have historically been used by both pro-slavery advocates and slavery abolitionists to support their respective views.

Feudalism[edit]

Feudalism was a set of political and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour. Although derived from the Latin word feodum (fief),[12]then in use, the term feudalism and the system it describes were not conceived of as a formal political system by the people living in the Medieval Period. In its classic definition, by François-Louis Ganshof (1944),[13] feudalism describes a set of reciprocal legal and military obligations among the warrior nobility, revolving around the three key concepts of lords, vassals and fiefs. There is also a broader definition, as described by Marc Bloch (1939), that includes not only warrior nobility but the peasantry bonds of manorialism, sometimes referred to as a "feudal society". Since 1974 with the publication of Elizabeth A. R. Brown's The Tyranny of a Construct, and Susan Reynolds' Fiefs and Vassals (1994), there has been ongoing inconclusive discussion among medieval historians if Feudalism is a useful construct for understanding medieval society.[14][15][16][17][18]

Serfdom[edit]

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century. Serfdom included the forced labor of serfs bound to a hereditary plot of land owned by a lord in return for protection and the right to work on fields they leased from their landlords to maintain their own subsistence. Serfdom involved not only work in owner's fields, but his mines, forests and roads. Manors formed the basic unit of society and the lord and his serfs were bound legally, economically, and socially. Serfs were laborers who were bound to the land; they formed the lowest social class of the feudal society. Serfs were also defined as people in whose labor landowners held property rights. Before the 1861 abolition of serfdom in Russia, a landowner's estate was often measured by the number of "souls" he owned. Feudalism in Europe evolved from agricultural slavery in the late Roman Empire and spread through Europe around the 10th century; it flourished in Europe during the Middle Ages but lasted until the 19th century in some countries. Although the decline of serfdom has sometimes been attributed to the Black Death, which reached Europe in 1347,[19] the decline had begun before that date. For example, serfdom was de facto ended in France by Philip IV, Louis X (1315), and Philip V (1318).[20][21] With the exception of a few isolated cases, serfdom had ceased to exist in France by the 15th century. In Early Modern France, French nobles nevertheless maintained a great number of seigneurial privileges over the free peasants that worked lands under their control. Serfdom was formally abolished in France in 1789.[22]

After the Renaissance, serfdom became increasingly rare in most of Western Europe but grew strong in Central and Eastern Europe, where it had previously been less common (this phenomenon was known as "later serfdom"). In England, the end of serfdom began with Tyler’s Rebellion and was fully ended when Elizabeth I freed the last remaining serfs in 1574.[21] There were native-born Scottish serfs until 1799, when coal miners previously kept in serfdom gained emancipation. However, most Scottish serfs had been freed before this time. In Eastern Europe the institution persisted until the mid-19th century. It persisted in Austria-Hungary till 1848 and was abolished in Russia in 1861.[23] In Finland, Norway and Sweden feudalism was not established, and serfdom did not exist. But serfdom-like institutions did exist in both Denmark (the stavnsbånd, from 1733 to 1788) and its colony Iceland (the much more restrictive vistarband, from 1490 until the late 19th century).

According to the census of 1857 the number of private serfs in Russia was 23.1 million.[24]

Colonialism[edit]

Christianity and colonialism are often closely associated because Catholicism and Protestantism were the religions of the European colonial powers.[25] Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups (called "missionaries"), to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not onlyevangelization (in order to expand Christianity through the conversion of new members), but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged. Missionaries have the authority to preach the Christian faith (and sometimes to administer sacraments), and provide humanitarian work to improve economic development, literacy,education, health care, and orphanages. Christian doctrines (such as the "Doctrine of Love" professed by many missions) permit the provision of aid without requiring religious conversion.

Christian missionaries and clergy in colonial territories have been portrayed as acting as the "religious arm" of those powers.[26] According to Edward Andrews, Christian missionaries were initially portrayed as "visible saints, exemplars of ideal piety in a sea of persistent savagery". However, by the time the colonial era drew to a close in the last half of the twentieth century, missionaries became viewed as “ideological shock troops for colonial invasion whose zealotry blinded them.”[27]

Christianity is targeted by critics of colonialism because the tenets of the religion were used to justify the actions of the colonists.[28] For example, Toyin Falola asserts that there were some missionaries who believed that "the agenda of colonialism in Africa was similar to that of Christianity".[29] Falola cites Jan H. Boer of the Sudan United Mission as saying, "Colonialism is a form of imperialism based on a divine mandate and designed to bring liberation -spiritual, cultural, economic and political - by sharing the blessings of the Christ-inspired civilization of the West with a people suffering under satanic oppression, ignorance and disease, effected by a combination of political, economic and religious forces that cooperate under a regime seeking the benefit of both ruler and ruled."[29]

Edward Andrews writes:

Historians have traditionally looked at Christian missionaries in one of two ways. The first church historians to catalogue missionary history provided hagiographic descriptions of their trials, successes, and sometimes even martyrdom. Missionaries were thus visible saints, exemplars of ideal piety in a sea of persistent savagery. However, by the middle of the twentieth century, an era marked by civil rights movements, anti-colonialism, and growing secularization, missionaries were viewed quite differently. Instead of godly martyrs, historians now described missionaries as arrogant and rapacious imperialists. Christianity became not a saving grace but a monolithic and aggressive force that missionaries imposed upon defiant natives. Indeed, missionaries were now understood as important agents in the ever-expanding nation-state, or “ideological shock troops for colonial invasion whose zealotry blinded them.”[citation needed]

According to Jake Meador, "some Christians have tried to make sense of post-colonial Christianity by renouncing practically everything about the Christianity of the colonizers. They reason that if the colonialists’ understanding of Christianity could be used to justify rape, murder, theft, and empire then their understanding of Christianity is completely wrong. "[30]

According to Lamin Sanneh, "(m)uch of the standard Western scholarship on Christian missions proceeds by looking at the motives of individual missionaries and concludes by faulting the entire missionary enterprise as being part of the machinery of Western cultural imperialism." As an alternative to this view, Sanneh presents a different perspective arguing that "missions in the modern era has been far more, and far less, than the argument about motives customarily portrays."[31]

Michael Wood asserts that the indigenous peoples were not considered to be human beings and that the colonisers was shaped by "centuries of Ethnocentrism, and Christian monotheism, which espoused one truth, one time and version of reality.”[32]

Western economic development[edit]

In two journal articles published in 1904-05, German sociologist Max Weber propounded a thesis that Reformed (i.e., Calvinist) Protestantism had engendered the character traits and values that under-girded modern capitalism. The English translation of these articles were published in book form in 1930 as "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Weber argued that capitalism in northern Europe evolved when the Protestant (particularlyCalvinist) ethic influenced large numbers of people to engage in work in the secular world, developing their own enterprises and engaging in trade and the accumulation of wealth for investment. In other words, the Protestant work ethic was a force behind an unplanned and uncoordinated mass action that influenced the development of capitalism.

This idea is also known as "the Weber thesis". Weber, however, rejected deterministic approaches, and presented the Protestant Ethic as merely one in a number of 'elective affinities' leading toward capitalist modernity. Weber's term Protestant work ethic has become very widely known. The work relates significantly to the cultural "rationalization" and so-called "disenchantment" which Weber associated with the modern West.

Weber's work focused scholars on the question of the uniqueness of Western civilization and the nature of its economic and social development. Scholars have sought to explain the fact that economic growth has been much more rapid in Western Europe and its overseas off shoots than in other parts of the world. Modern economic growth has taken place with a quite different economic and social structure from that which had existed earlier. Economic growth occurred at roughly the same time, or soon after, these areas experienced the rise of Protestant religions. Stanley Engerman asserts that, although some scholars may argue that the two phenomena are unrelated, many would find it difficult to accept such a thesis.[33]

John Chamberlain wrote that "Christianity tends to lead to a capitalistic mode of life whenever siege conditions do not prevail... [capitalism] is not Christian in and by itself; it is merely to say that capitalism is a material by-product of the Mosaic Law."[34]

Rodney Stark propounds the theory that Christian rationality is the primary driver behind the success of capitalism and the Rise of the West.[35]

Social justice[edit]

Social justice generally refers to the idea of creating a society or institution that is based on the principles of equality and solidarity, that understands and values human rights, and that recognizes the dignity of every human being.[36][37] The term and modern concept of "social justice" was coined by the Jesuit Luigi Taparelli in 1840 based on the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas and given further exposure in 1848 by Antonio Rosmini-Serbati.[36][37][38][39][40] The idea was elaborated by the moral theologian John A. Ryan, who initiated the concept of a living wage. Father Coughlin also used the term in his publications in the 1930s and the 1940s. It is a part of Catholic social teaching, Social Gospel from Episcopalians and is one of the Four Pillars of the Green Party upheld by green parties worldwide. Social justice as a secular concept, distinct from religious teachings, emerged mainly in the late twentieth century, influenced primarily by philosopher John Rawls. Some tenets of social justice have been adopted by those on the left of the political spectrum.

Catholic social teaching[edit]

Catholic social teaching is a body of doctrine developed by the Catholic Church on matters of poverty and wealth, economics, social organization and the role of the state. Its foundations are widely considered to have been laid by Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical letter Rerum Novarum, which advocated economic Distributismand condemned Socialism.

According to Pope Benedict XVI, its purpose "is simply to help purify reason and to contribute, here and now, to the acknowledgment and attainment of what is just…. [The Church] has to play her part through rational argument and she has to reawaken the spiritual energy without which justice…cannot prevail and prosper",[41]According to Pope John Paul II, its foundation "rests on the threefold cornerstones of human dignity, solidarity and subsidiarity".[42] These concerns echo elements ofJewish law and the prophetic books of the Old Testament, and recall the teachings of Jesus Christ recorded in the New Testament, such as his declaration that "whatever you have done for one of these least brothers of Mine, you have done for Me."[43]

Catholic social teaching is distinctive in its consistent critiques of modern social and political ideologies both of the left and of the right: liberalism, communism, socialism, libertarianism, capitalism,[44] fascism, and Nazism have all been condemned, at least in their pure forms, by several popes since the late nineteenth century.

Marxism[edit]

Arnold Toynbee characterized Communist ideology as a "Christian heresy".[45] Donald Treadgold interprets Toynbee's characterization as applying to Christian attitudes as opposed to Christian doctrines.[46] In his book, "Moral Philosophy", Jacques Maritain echoed Toynbee's perspective, characterizing the teachings of Karl Marx as a "Christian heresy".[47]

Liberation theology[edit]

Liberation theology[48] is a Christian movement in political theology which interprets the teachings of Jesus Christ in terms of a liberation from unjust economic, political, or social conditions. It has been described by proponents as "an interpretation of Christian faith through the poor's suffering, their struggle and hope, and a critique of society and the Catholic faith and Christianity through the eyes of the poor",[49] and by detractors as Christianized Marxism.[50] Although liberation theology has grown into an international and inter-denominational movement, it began as a movement within theRoman Catholic church in Latin America in the 1950s–1960s. Liberation theology arose principally as a moral reaction to the poverty caused by social injustice in that region. The term was coined in 1971 by the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, who wrote one of the movement's most famous books, A Theology of Liberation. Other noted exponents are Leonardo Boff of Brazil, Jon Sobrino of El Salvador, and Juan Luis Segundo of Uruguay.[51][52][53]

The influence of liberation theology diminished after proponents using Marxist concepts were admonished by the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) in 1984 and 1986. The Vatican criticized certain strains of liberation theology for focusing on institutional dimensions of sin to the exclusion of the individual; and for allegedly misidentifying the church hierarchy as members of the privileged class.[54]

References[edit]

- ^ Mahoney, Jack (1995). Companion encyclopedia of theology. Taylor & Francis. p. 759.

- ^ Cobb, Jr., John B. "Eastern Views of Economics". Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ a b c d Did Christianity Cause the Crash? Hanna Rosin, December 2009

- ^ a b Van Biema, David; Chu, Jeff (September 10, 2006). "Does God Want You To Be Rich?". Time (magazine). Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ^ Lausanne Theology Working Group, Africa chapter (12-08-2009). "A Statement on Prosperity Teaching". Christianity Today.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Africa: Poverty & 'Prosperity'". Patheos. January 15, 2010.

- ^ Roover, Raymond (Autumn 1967). "The Scholastics, Usury, and Foreign Exchang". Business History Review. 41 (3). The Business History Review, Vol. 41, No. 3: 257–271. doi:10.2307/3112192. JSTOR 3112192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ The letter is quoted in Le Van Baumer, Franklin, editor (1978). Main Currents of Western Thought: Readings in Western Europe Intellectual History from the Middle Ages to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02233-6.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ See Haas, Guenther H. (1997). The Concept of Equity in Calvin's Ethics. Waterloo, Ont., Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 117ff. ISBN 0-88920-285-0.

- ^ "African Holocaust Special". African Holocaust Society. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- ^ History of Abolitionism

- ^ feodum - see The Cyclopedic Dictionary of Law, by Walter A. Shumaker, George Foster Longsdorf, pg. 365, 1901.

- ^ François Louis Ganshof(1944). Qu'est-ce que la féodalité. Translated into English as Feudalism by Philip Grierson, foreword by F.M. Stenton. 1st ed.: New York and London, 1952; 2nd ed: 1961; 3d ed: 1976.

- ^ Brown, Elizabeth A. R. (October 1974). "The Tyranny of a Construct: Feudalism and Historians of Medieval Europe". The American Historical Review. 79 (4). American Historical Association: 1063–1088. doi:10.2307/1869563. JSTOR 1869563. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ "Feudalism", by Elizabeth A. R. Brown. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ "Feudalism?", by Paul Halsall. Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- ^ "The Problem of Feudalism: An Historiographical Essay", by Robert Harbison, 1996, Western Kentucky University.

- ^ Reynolds, Susan, Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994 ISBN 0-19-820648-8

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Maurice Druon, Le Roi de fer, Chapter 3

- ^ a b 1902encyclopedia.com

- ^ Serfdom - LoveToKnow 1911

- ^ Serf. A Dictionary of World History

- ^ Russia by Donald Mackenzie Wallace

- ^ Colonialism: an international, social, cultural, and political encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2003. p. 496.

Of all religions, Christianity has been most associated with colonialism because several of its forms (Catholicism and Protestantism) were the religions of the European powers engaged in colonial enterprise on a global scale.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Bevans, Steven. "Christian Complicity in Colonialism/ Globalism" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-11-17.

The modern missionary era was in many ways the 'religious arm' of colonialism, whether Portuguese and Spanish colonialism in the sixteenth Century, or British, French, German, Belgian or American colonialism in the nineteenth. This was not all bad — oftentimes missionaries were heroic defenders of the rights of indigenous peoples

- ^ Andrews, Edward (2010). "Christian Missions and Colonial Empires Reconsidered: A Black Evangelist in West Africa, 1766–1816". Journal of Church & State. 51 (4): 663–691. doi:10.1093/jcs/csp090.

Historians have traditionally looked at Christian missionaries in one of two ways. The first church historians to catalogue missionary history provided hagiographic descriptions of their trials, successes, and sometimes even martyrdom. Missionaries were thus visible saints, exemplars of ideal piety in a sea of persistent savagery. However, by the middle of the twentieth century, an era marked by civil rights movements, anti-colonialism, and growing secularization, missionaries were viewed quite differently. Instead of godly martyrs, historians now described missionaries as arrogant and rapacious imperialists. Christianity became not a saving grace but a monolithic and aggressive force that missionaries imposed upon defiant natives. Indeed, missionaries were now understood as important agents in the ever-expanding nation-state, or "ideological shock troops for colonial invasion whose zealotry blinded them.

- ^ Meador, Jake. "Cosmetic Christianity and the Problem of Colonialism – Responding to Brian McLaren". Retrieved 2010-11-17.

According to Jake Meador, "some Christians have tried to make sense of post-colonial Christianity by renouncing practically everything about the Christianity of the colonizers. They reason that if the colonialists' understanding of Christianity could be used to justify rape, murder, theft, and empire then their understanding of Christianity is completely wrong.

- ^ a b Falola, Toyin (2001). Violence in Nigeria: The Crisis of Religious Politics and Secular Ideologies. University Rochester Press. p. 33.

- ^ Meador, Jake. "Cosmetic Christianity and the Problem of Colonialism – Responding to Brian McLaren". Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ Sanneth, Lamin (April 8, 1987). "Christian Missions and the Western Guilt Complex". The Christian Century. The Christian Century Foundation: 331–334. Retrieved 2010-12-02.

- ^ Conquistadors, Michael Wood, p. 20, BBC Publications, 2000

- ^ Engerman, Stanley L. (2000-02-29). "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism". Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- ^ Chamberlain, John (1976). The Roots of Capitalism.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (2005). The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success. New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6228-4.

- ^ a b Education and Social Justice By J. Zajda, S. Majhanovich, V. Rust, 2006, ISBN 1-4020-4721-5

- ^ a b Nursing ethics: across the curriculum and into practice By Janie B. Butts, Karen Rich, Jones and Bartlett Publishers 2005, ISBN 978-0-7637-4735-0

- ^ Battleground criminal justice by Gregg Barak, Greenwood publishing group 2007, ISBN 978-0-313-34040-6

- ^ Engineering and Social Justice By Donna Riley, Morgan and Claypool Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-1-59829-626-6

- ^ Spirituality, social justice, and language learning By David I. Smith, Terry A. Osborn, Information Age Publishing 2007, ISBN 1-59311-599-7

- ^ (Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, 28).

- ^ (John Paul II, 1999 Apostolic Exhortation, Ecclesia in America, 55).

- ^ Matthew 25:40.

- ^ Quadragesimo Anno § 99 ff

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold (1961). A Study of History. p. 545.

The Communist ideology was a Christian heresy in the sense that it had singled out several elements in Christianity and had concentrated on these to the exclusion of the rest. It had taken from Christianity its social ideals, its intolerance and its fervour.

- ^ Treadgold, Donald W. (1973). The West in Russia and China: Russia, 1472-1917. Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780521085526.

- ^ Maritain, Jacques. Moral Philosophy.

This is to say that Marx is a heretic of the Judeo-Christian tradition, and that Marxism is a 'Christian heresy', the latest Christian heresy

- ^ In the mass media, 'Liberation Theology' can sometimes be used loosely, to refer to a wide variety of activist Christian thought. In this article the term will be used in the narrow sense outlined here.

- ^ Berryman, Phillip, Liberation Theology: essential facts about the revolutionary movement in Latin America and beyond(1987)

- ^ "[David] Horowitz first describes liberation theology as 'a form of Marxised Christianity,' which has validity despite the awkward phrasing, but then he calls it a form of 'Marxist–Leninist ideology,' which is simply not true for most liberation theology..." Robert Shaffer, "Acceptable Bounds of Academic Discourse," Organization of American Historians Newsletter 35, November, 2007. URL retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ Richard P. McBrien, Catholicism(Harper Collins, 1994), chapter IV.

- ^ Liberation Theology General Information, onBelieve, an online religious information source

- ^ Gustavo Gutierrez, A Theology of Liberation, First (Spanish) edition published in Lima, Peru, 1971; first English edition published by Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York), 1973.

- ^ Wojda, Paul J., "Liberation theology", in R.P. McBrien, ed., The Catholic Encyclopedia (Harper Collins, 1995).

Further reading[edit]

- Rosenberg, Nathan; Birdzell, Luther Earle (1986). How the West Grew Rich: The Economic Transformation of the Industrial World. Basic Books.