User:Orser67/Thirteen Colonies

The history of the Thirteen Colonies began in 1607 with the founding Jamestown. English colonization of North America continued in the following decades with the establishment of more colonies on the present-day East Coast of the United States. By 1740, there were thirteen contiguous colonies, each administered separately as part of the British Empire. The Thirteen Colonies collectively declared independence in 1776 and won British recognition of that independence with the signing of the 1783 Treaty of Paris. After gaining independence, the Thirteen Colonies became known as the United States.

North America had been inhabited by Native Americans for thousands of years of prior to 1492, but European exploration of North America began after Christopher Columbus's 1492 expedition across the Atlantic Ocean. English exploration of the continent commenced shortly thereafter, and Sir Walter Raleigh established Roanoke Colony in 1585. With the settlement of Jamestown on the Chesapeake Bay in 1607, the English established their first successful, permanent colony in North America, which became known as the Colony of Virginia. In 1620, a group of Puritans established a second permanent colony on the coast of Cape Cod. The success of these colonies inspired further English colonization. The Province of Maryland was established to the north of the Virginia and the Province of Carolina was established to Virginia's south. The Puritans founded several more colonies in the region that became known as New England. In the Anglo-Dutch Wars, the English took control of New Netherland. The former territories of New Netherland became known as the Middle Colonies, consisting of New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey. King James II of England attempted to centralize control of the colonies and established the Dominion of New England, but the dominion was abolished after James II was overthrown in England's Glorious Revolution.

After the Glorious Revolution, the English continued to enforce many of their centralizing policies, including the mercantilist Navigation Acts, though the colonies nonetheless retained a large degree of independence. After the 1707 Acts of Union, the English and Scottish crowns were united, and the English colonies became part of the British Empire. The last of the Thirteen Colonies were established in the early 18th century, as Georgia was established and the Carolina was split into the North Carolina and the South Carolina. After the Glorious Revolution, English and British monarchs came into repeated conflict with France, which had established colonies to the west and north of the English domain in North America. In a series of wars, the two empires fought for control of the North American continent. In the French and Indian War, the North American component of the global Seven Years' War, the British Empire defeated France and won control of North America east of the Mississippi River.

Following the French and Indian War, the British imposed new taxes and other unpopular policies on the Thirteen Colonies, leading to dissent against British rule. The American Revolution began in 1775 when colonists and British soldiers came into conflict, and the Thirteen Colonies jointly declared their independence in 1776. The colonies established a new government under the Articles of Confederation, which provided for a loose coalition of sovereign states, and the Thirteen Colonies became known as the United States. With the aid of France and other European powers in the American Revolutionary War, the United States won independence and gained control of former British territory extending to the Mississippi River.

Early exploration and colonization of North America[edit]

Inspired by the writings of Marco Polo, the expedition of Christopher Columbus set sail from Spain in 1492. Though Columbus sought a western route between Europe and Asia, he instead discovered the Americas. With the aid of coerced Native American labor, Spain and another European maritime power, Portugal, quickly established colonies in the New World after Columbus returned from his voyage, beginning the European colonization of the Americas.[1] Spanish explorers such as Hernando de Soto and Juan Ponce de León led expeditions through parts of the present-day United States, but the lack of readily-apparent precious metals or other valuable materials made settlement north of the Caribbean Sea undesirable to the conquistadors. After a group of French Huguenots established the colony of Fort Caroline (in Northeast Florida) in 1564, the Spanish destroyed the colony and established Fort Augustine nearby. Spain defeated this early attempt at colonization by a rival power, but the episode reflected the growing European appreciation for the riches that Spain and Portugal had acquired from the New World.[2]

The other major powers of 15th-century Western Europe, France and England, employed explorers soon after the return of Columbus's first voyage. In 1497, King Henry VII of England dispatched an expedition led by John Cabot to explore the coast of North America. The lack of precious metals or other riches discouraged English settlement just as it had with Spain, but the European powers continued to show some interest in the land north of the Caribbean Sea. In 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano mapped the coast of North America between present-day South Carolina and Maine, while Jacques Cartier explored part of the Saint Lawrence River.[3] Explorers such as Martin Frobisher and Henry Hudson sailed to the New World in search of a Northwest Passage between the Atlantic Ocean and Asia, but were unable to find a viable route. Native Americans east of the Mississippi River became somewhat familiar with European culture through direct and indirect trade, while Europeans established fisheries in the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.[4] Europeans active in this region traded metal, glass, and cloth for food and fur, beginning the North American fur trade.[5] The Native Americans acquired goods such as firearms and alcohol that had little or no precedent in North America, as well as less revolutionary items such as metal tools and weapons. This European contact spurred major cultural changes in North America even before the presence of the first permanent European settlements.[6]

In the late sixteenth century, Protestant England became embroiled in a religious war with Catholic Spain. Seeking to weaken Spain's economic and military power, English privateers such as Francis Drake and Humphrey Gilbert harassed Spanish shipping.[7] Gilbert proposed the colonization of North America on the Spanish model, with the goal of creating a profitable English empire that could also serve as a base for the privateers. After Gilbert's death, Walter Raleigh took up the cause of North American colonization. He named the proposed English colony "Virginia" after his patron, Queen Elizabeth I of England. Raleigh dispatched an expedition of 500 men to Roanoke Island, establishing in 1584 the first permanent English colony in North America.[8] The colonists were poorly prepared for life in the New World, and the Roanoke Colony quickly alienated nearby Native Americans. By 1590, its colonists had disappeared.[9] Despite the failure of the colony, the English remained interested in the colonization of North America for economic and military reasons.[10]

17th century[edit]

First permanent English colonies[edit]

In 1606, King James I of England granted charters to both the Plymouth Company and the London Company for the purpose of establishing permanent settlements in North America. In 1607, the London Company established a colony at Jamestown on the Chesapeake Bay, while the Plymouth Company founded the short-lived Popham Colony on the Kennebec River. The colonists at Jamestown faced extreme adversity, and by 1617 there were only 351 survivors out of the the 1700 colonists who had been transported to Jamestown. In 1608, the English attempted to make the paramount chief of the nearby Powhatan Confederacy a vassal of King James, but the chief refused the offer.[11] The colonial leaders hoped to replicate the English conquest of Ireland, where English lords presided over the native population, but the Native Americans did not prove amenable to the idea.[12] After the ouster of English leader John Smith in 1609, the English and the natives engaged in a war which lasted until 1614, when settler John Rolfe married Pocahontas, the daughter of the paramount chief.[13] At roughly the same time, the Virginians discovered the profitability of growing tobacco, and the settlement's population boomed from 400 settlers in 1617 to 1240 settlers in 1622. That same year, war resumed between the settlers and Native Americans, and Jamestown faced native hostility for the next decade. The London Company was bankrupted by the frequent warring, and the English crown took direct control of the Colony of Virginia, as Jamestown and its surround environs became known.[14] Overproduction of tobacco after 1630 led to economic difficulties, but Virginia continued to attract English immigrants eager to settle new lands.[15]

Ferdinando Gorges, the lead investor of the failed Plymouth Company, established another joint-stock company to oversee English settlement of the region north of Jamestown. The Plymouth Council for New England sponsored several colonization projects, including a colony established by a group of English Puritans, known today as the Pilgrims.[16] The Puritans embraced an intensely emotional form of Calvinist Protestantism, and sought independence from the Church of England.[17] In 1620, the Mayflower transported the Pilgrims across the Atlantic and the Pilgrims established Plymouth Colony on the coast of Cape Cod. Previous activities in the region, including the acquisition of slaves, had given the English settlers a poor reputation among the nearby natives, who were thus reluctant to interact with the English colony. The Pilgrims endured an extremely hard first winter, with roughly fifty of the one hundred colonists dying. In 1621, Plymouth Colony was able to establish an alliance with the nearby Wampanoag tribe with the help of Squanto, an English-speaking Native American. The Wampanoag proved to be invaluable trading partners and allies to the colonists, helping the Pilgrims survive in the new land. With the help of the Wampanoag, Plymouth Colony established effective agricultural practices and thrived on trade of fur and other materials with Native Americans.[18]

Colonization by other powers[edit]

The Netherlands, Sweden, and France established their first successful North American colonies at roughly the same time as the English. These powers, as well as Spain, competed with the English for economic and political success in the New World. Eventually, parts or all of the French, Dutch, Swedish, and Spanish colonies would be absorbed into the English colonial empire.

New Netherlands and New Sweden[edit]

Beginning in 1609, Dutch traders explored and established fur trading posts on the Hudson River, Delaware River, and Connecticut River. Seeking to protect their interests in the fur trade, the Dutch West India Company established permanent settlements on the Hudson River, creating the Dutch colony of New Netherland. In 1626, Peter Minuit, the director of the colony, purchased the island of Manhattan from a group of Lenape and established the outpost of New Amsterdam.[19] Though relatively few Dutch settled in New Netherland, the colony came to dominate the regional fur trade.[20] It also served as the base for extensive trade with the English colonies, and many products produced in New England or Virginia were carried to Europe on Dutch ships.[21] The Dutch also engaged in the burgeoning Atlantic slave trade, supplying enslaved Africans to the English colonies in North America and Barbados.[22] Though many English colonists supported Dutch commerce, government officials in England resented the loss of revenue from customs duties on English imports.[23] Despite commercial success and the West India Company's desire to grow the colony, New Netherland failed to attract the same level of settlement as the English colonies. Many of those who did immigrate to the colony were English, German, Walloon, or Sephardim.[24]

In 1638, Sweden established the colony of New Sweden in the Delaware Valley. Though chartered by Sweden, the operation was led by former members of the Dutch West India Company, including Minuit.[25] New Sweden established extensive trading contacts with English colonies to the south, and shipped much of the tobacco produced in Virginia.[26] New Sweden was conquered by the Dutch in 1655,[27] while Sweden was engaged in the Second Northern War.

Beginning in the 1650s, the English and Dutch engaged in a series of wars, and the English sought to conquer New Netherland.[28] With the aid of the New England colonies, Richard Nicolls captured the lightly-defended New Amsterdam in 1664. His subordinates quickly captured the remainder of New Netherland.[29] The 1667 Treaty of Breda ended the Second Anglo-Dutch War and confirmed English control of the region.[30] The Dutch briefly re-gained control of parts of New Netherland in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, but surrendered claim to the territory in the 1674 Treaty of Westminster, ending the Dutch colonial presence in North America.[31]

New France[edit]

King Henry IV of France granted a royal charter to Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons, and de Mons dispatched Samuel de Champlain to establish a permanent settlement with the goal of controlling the fur trade. Champlain established Quebec City on the St. Lawrence River in 1608.[32] Though the colony faced conflicts with Native Americans and was briefly conquered by Virginia privateers, it became the center of the French colony of Canada.[33] While settlers flocked to the English colonies in the first half of the 17th century, Canada experienced slow growth.[34] King Louis XIV of France and chief minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert reinvigorated French colonization efforts in the mid-17th century, and France extended its influence into the Great Lakes region. In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle traveled from the Great Lakes down the Mississippi River, claiming the territory of Louisiana for France.[35] From its colonies in Louisiana and Canada, the French subsidized their Native American allies in the hope of containing the Thirteen Colonies to the Atlantic Coast.[36] The French and Spanish colonies would serve as a foil in the development of a cultural indentity in the Thirteen Colonies, as the colonists defined themselves in opposition to the supposedly decadent and despotic French and Spanish cultures.[37]

Native American resistance[edit]

As the European empires established their first permanent settlements in North America, Native Americans suffered from the diseases brought from the Old World in the Columbian Exchange. The societies of the Eastern Hemisphere had lived among domesticated animals for millennia, providing a fertile ground for the development of deadly viral diseases such as smallpox, measles, and chicken pox.[38] The extent to which these diseases affected North America before the 1600 is uncertain, but the Roanoke colonists noted the striking impact of diseases in nearby Native American societies. After 1600, the Native Americans suffered numerous epidemics, with whole villages destroyed by smallpox and other diseases. These epidemics weakened the ability of the Native Americans to resist European colonization, but also provoked widespread resentment against the newcomers who were (correctly) assumed to have brought the diseases.[39] Though weakened by disease and often interested in trade, many Native Americans proved to be deadly foes to European settlers. Acquiring and adapting to European weaponry, the Iroquois and other tribes conquered their neighbors and frequently raided European settlements, creating a formidable obstacle to further European settlement.[40] Many Native Americans would eventually come to favor the French, whose less densely-populated settlements posed less of a threat to Native American lands.[41]

| Colony | Year[42] | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Virginia | 1607 | Charter[43] |

| Plymouth | 1620 | Charter[43] |

| Massachusetts Bay | 1630 | Charter[43] |

| Maryland | 1634 | Proprietary[44] |

| Saybrook[45] | 1635 | Charter |

| Connecticut | 1636 | Charter |

| Rhode Island | 1636 | Charter |

| New Haven[45] | 1637 | Charter |

| Carolina | 1663 | Proprietary |

| New York | 1664 | Proprietary[43] |

| East Jersey | 1674 | Proprietary |

| West Jersey | 1674 | Proprietary |

| New Hampshire | 1679 | Crown |

| Pennsylvania | 1681 | Proprietary |

| Delaware | 1701 | Proprietary |

| New Jersey | 1702 | Crown |

| North Carolina | 1729 | Crown[43] |

| South Carolina | 1729 | Crown[43] |

| Georgia | 1732 | Proprietary[43] |

Southern Colonies[edit]

In 1632, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore founded the Province of Maryland to the north of Virginia. Maryland was briefly governed as part of Virginia in the 1650s, but reasserted its independence in 1657.[46] Maryland and Virginia became known as the Chesapeake Colonies, and experienced similar immigration and economic activities.[47] Though Baltimore and his descendants intended for the colony to be a refuge for Catholics, it attracted more Protestant immigrants, who scorned the Calvert family's policy of religious toleration. Nonetheless, the Calverts would continue to exercise control over Maryland for decades, serving as a model for other proprietary colonies.[48]

While early settlers in New England often settled as families, the population of the Chesapeake Colonies was overwhelmingly male.[49] The Chesapeake Colonies also hosted a large population of indentured servants who paid for their trip across the Atlantic by promising their labor for several years.[50] Aided by this free labor, a planter elite came to dominate Virginia politically and economically.[51] In the mid-17th century, the Chesapeake Colonies, inspired by the success of slavery in the English colony of Barbados, began the mass importation of African slaves. Though many early slaves eventually gained their freedom, after 1662 Virginia adopted policies that passed enslaved status from mother to child and granted slave owners near-total domination of their human property.[52]

In 1646, the Virginia Colony under Governor William Berkeley defeated the Powhatan Confederacy, forcing it to cede most of its territory and requiring an annual tribute.[53] Tensions continued with other tribes, and in 1676, Bacon's Rebellion broke out against the rule of Governor Berkeley. The rebellion began with Nathaniel Bacon's demand for more aggressive policies against the Native Americans, but it became a civil war that engulfed the colony.[54] Bacon mobilized resentment against the mercantilist policies of England and the economic and political power of the elite planter class.[55] The rebellion ended with Bacon's death, but it also ended the rule of Governor Berkeley.[56]

The Spanish established dominance over the Native American tribes in Florida but attracted few European settlers to the colony.[57] They sponsored a series of missions led by Franciscan friars to create a buffer zone of loyal Native American subjects, but the colony frequently suffered raids from rival tribes.[58] Encouraged by the apparent weakness of Spanish rule in Florida, Barbadian planter John Colleton and seven other supporters of Charles II of England established the Province of Carolina in 1663. Though a previous royal charter for the colony had been granted, the lands south of Virginia were sparsely settled prior to the 1660s.[59] Settlers in the Carolina Colony established two main population centers, with many Virginians settling in the north of the province and many English Barbadians settling in the southern port city of Charles Town.[60] The Carolina Colony allied with the Yamassee Indians to conquer other Native Americans in conflicts such as the Tuscarora War, but eventually destroyed the Yamassee in the Yamasee War of 1715-1717.[61]

New England Colonies[edit]

Following the success of the Jamestown and Plymouth Colonies, several more English groups established colonies in the region that became known as New England. In 1629, another group of Puritans led by John Winthrop established the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and created an economic and military alliance with the Narragansett tribe. By 1635, roughly ten thousand English settlers lived in the region between the Connecticut River and the Kennebec River.[62] Between 1636 and 1638, the English settlers and their Native American allies fought the Pequot War against the Pequot tribe, which had played an important role in the fur trade. The English settlers prevailed in the war, destroying the Pequots as a polity and establishing their dominance over the remaining local tribes with the Treaty of Hartford.[63] Puritan settlers established the Connecticut Colony in the region the Pequots had formerly controlled, and established an alliance with a group of former Pequots known as the Mohegan.[64] Another group of settlers established the New Haven Colony to the west of the Connecticut Colony.[65]

In 1643, the five Puritan colonies founded the New England Confederation to provide for mutual defense against the Dutch and hostile Native Americans.[66] Two other English colonies, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations and Saybrook Colony, did not join the confederation, although Saybrook was incorporated into the Connecticut Colony in 1644. Rhode Island was founded by Roger Williams, a Puritan leader who was expelled from the Massachusetts Bay Colony after he advocated for a formal split with the Church of England. Rhode Island was granted an unprecedented parliamentary charter in 1644, and experienced tensions with its neighboring colonies.[67] Aside from Rhode Island, the New England colonies developed a religious practice known as Congregationalism, with individual churches acting autonomously.[68] As New England was a relatively cold and infertile region, the New England colonies relied on fishing and long-distance trade to sustain the economy.[69]

England sought to assert more centralized control of the New England colonies in the second half of the 17th century, but the expense of the war with the Dutch ensured only limited English control of the colonies, especially in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1662, Charles II of England granted charters to Connecticut Colony and Rhode Island Colony. Connecticut's participation in the capture of New Netherland was rewarded with a generous western border set at the midpoint between the Connecticut and Hudson rivers, thus setting the western border of New England.[70] Throughout New England, the colonists opposed Charles II's policies of religious toleration, which they feared would eventually lead to the establishment of a neo-feudal system in the New World.[71] In the 1690s, as the New England colonies became increasingly fearful about threats from Catholics and Native Americans, the small New England town of Salem held a series of witch trials which resulted in the executions of twenty people.[72] The trials were disbanded by royal governor William Phips in 1693.[73]

Middle Colonies[edit]

In the 1664, the Duke of York, later known as James II of England, was granted control of the English colonies north of the Delaware River. After his forces captured New Netherland that same year, James created the Province of New York out of the former Dutch territory, and New Amsterdam was re-named to New York City.[74] He also created the provinces of West Jersey and East Jersey out of former Dutch land situated to the west of New York City, giving the territories to John Berkeley and George Carteret.[75] East Jersey and West Jersey would later be unified as the Province of New Jersey in 1702. On behalf of Duke of York, Governor Richard Nicolls pursued a policy of centralized control and religious toleration in New York and the other colonies.[76] His eventual successor, Governor Edmund Andros, extended New York's control of the Hudson River and lured the Native Americans of Mohawk Valley out of the French sphere of influence.[77]

Admiral William Penn played a key role in the restoration of the Stuart Dynasty and loaned Charles II large sums of money. After the admiral's death, Charles rewarded Penn's son, also named William Penn, with the land situated between Maryland and the Jerseys. Penn named this land the Province of Pennsylvania. Charles's grant relied on an inaccurate map, causing a border dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania that would endure until the drawing of the Mason–Dixon line in the 1760s.[78] Penn was also granted a lease to the Delaware Colony, which gained its own legislature in 1701. A devout Quaker, Penn sought to create a haven of religious toleration in the New World.[79] Pennsylvania attracted Quakers and other settlers from across Europe, who joined the Swedish and Dutch already living in the colony. The city of Philadelphia quickly emerged as a thriving port city.[80] With its fertile and cheap land, Pennsylvania became one of the most attractive destinations for immigrants in the late 17th century, and the colony would continue to grow in the 18th century.[81]

Increased royal oversight after 1675[edit]

In 1675, as English colonists increasingly came to dominate New England, King Philip's War broke out between the colonists and Native Americans. Wampanoag chieftain Metacomet (who the English called "King Philip") recruited several Native American tribes in the war against the colonists, and his forces had destroyed thirteen of the roughly ninety English towns by the end of 1675.[82] With the aid of New York Governor Andros, the New England colonies defeated Metacomet's forces in 1676. The war damaged the English colonies, but proved even more disastrous for the local Native American population, which fell by half.[83] After the war, Andros convinced the crown to send Edward Randolph reassert royal control over Massachusetts Bay. The crown detached the region north of the Merrimack River from the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1679, creating the Province of New Hampshire.[84] In the late 1680s, James incorporated the eight English colonies to the east of Pennsylvania into the Dominion of New England, and Andros served as the colonial governor. The new arrangement, designed to strengthen royal control, proved unpopular in the colonies. During the Glorious Revolution, the colonists rose up against and quickly captured Andros, and the New England colonies re-established their former governments.[85] In New York, Jacob Leisler led Dutch colonists and others dissatisfied with Andros's rule in Leisler's Rebellion.[86]

After deposing Andros, the colonists declared their allegiance to the new joint monarchy of William and Mary, but feared that the new monarchs would impose similar centralizing policies to those of James II.[87] William and Mary quickly confirmed these fears, reinstating many of the James's policies, including the mercantalist Navigation Acts and the Board of Trade.[88] The joint monarchy sent an expedition led by Richard Ingoldesby and Henry Sloughter to assert royal control of New York, and after a skirmish Sloughter captured and executed Leisler.[89] Installed as the governor of New York, Sloughter sought to inaugurate a new model of colonial government that shifted power to royal representatives and the Board of Trade.[90] Like New York, Massachusetts Bay Colony was reorganized as a royal colony with a governor appointed by the king. Plymouth Colony and the Province of Maine were incorporated into the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[91] Maryland, which had experienced a revolution against the Calvert family, also became a royal colony, though the Calverts retained much of their land and revenue in the colony.[92] Even those colonies that retained their charters or proprietors were forced to assent to much greater royal control than had existed before the 1690s.[93]

England in the 17th century[edit]

| Ruler | Reign |

|---|---|

| Elizabeth I | 1558-1603 |

| James I | 1603-1625 |

| Charles I | 1625-1649 |

| Oliver Cromwell | 1653-1658 |

| Richard Cromwell | 1658-1659 |

| Charles II | 1660-1685 |

| James II | 1685-1689 |

| William III and Mary II | 1689-1694 |

| William III | 1694-1702 |

| Anne | 1702-1714 |

| George I | 1714-1727 |

| George II | 1727-1760 |

| George III | 1760-1820 |

Between 1630 and 1660, over 50,000 English settlers migrated from England to North America. These settlers were driven largely by demographic pressures, as England's population had doubled in the century preceding 1635.[94] England also suffered from the effects of the Little Ice Age, a period of cooling that led to poor agricultural conditions.[95] Large landowners sought to enclose lands for their own benefit, limiting the amount of land available for individual farming.[96] Real wages of average English people fell dramatically, and many fell into poverty.[97] Even many younger sons of the lesser gentry were lured to emigrate to North America by the prospect of new lands to settle.[98]

Aside from these demographic and economic pressures, the political and religious situation in England also encouraged migration. King Charles I, who reigned in England and Scotland from 1625 to 1649, alienated his predominantly-Protestant subjects with his religious policies and flirtation with the Catholic powers of Spain and France. Like his father, Charles espoused an absolutist vision of monarchy that sought to minimize the role of elected officials and local leaders. His taxation policies proved especially unpopular.[99] The rejection of Calvinist doctrine by Charles and Archbishop William Laud aroused disaffection among the Puritans and other groups, and many decided to emigrate to New England, Virginia, and the West Indies.[100]

Scottish opposition to Charles's religious policies led to the Bishops' Wars, the cost of which force Charles to summon the Parliament of England in 1642. The Long Parliament began passing laws contrary to the king's wishes, and the struggle for control of England developed into the English Civil War. Parliamentary forces triumphed in 1649, and Charles was executed and succeeded by Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell.[101] After Cromwell's death, the Stuart Dynasty was returned to the throne in the form of Charles II, who reigned from 1660 to 1685.[102] England under Charles II passed a stronger version of the 1651 Navigation Act, a mercantilist policy that sought to restrict colonial trade with countries other than England.[103] Charles II sought to raise crown revenue by competing with and warring against the Dutch Empire, whose Atlantic trading activities sapped customs revenue.[104] At the same time, Parliament passed a series of laws known as the Clarendon Code, which sought to impose religious uniformity and indirectly encouraged immigration among dissenting Protestant groups.[105] Charles II was succeeded by his brother, James II, in 1685. James lost the support of his subjects after the birth of his Catholic heir, and he was overthrown in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 by his daughter, Mary II, and her husband, William III.[106]

The Glorious Revolution and its aftermath saw the passage of 1689 Bill of Rights, which promised increased power to Parliament and the protection of certain individual rights, as well as the Act of Toleration, which promised religious freedoms to non-Anglican Protestants. These religiously tolerant policies would be enforced in the colonies as well as in England. The succession of William III, who had long resisted French hegemony as the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, ensured that England and its colonies would come into conflict with the French empire of Louis XIV.[107] England became involved in the Nine Years' War against French expansionism in Europe, and England would fight several subsequent wars against France in the 18th century.[108]

In the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, the Parliament and the monarchy forged an effective governing alliance, with the monarch acting as the executive and Parliament providing oversight and controlling funds.[109] After the death of Mary II and William III, Mary's sister, Anne, acceded to the throne. In 1707, the English and Scottish parliaments passed the Acts of Union, combining the two polities into the Kingdom of Great Britain. Britain experienced an economic boom in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, and Britain and its colonies both experienced newfound material wealth in a phenomenon known as the consumer revolution.[110]

Early 18th century[edit]

Settlement and expansion of the colonies[edit]

The Carolina Colony suffered from a lack of unified leadership, as the descendants of the colony's proprietors fought over the direction of the colony.[111] After the Yamasee War devastated the local economy and depopulated the region, the colonists of Charles Town deposed their governor and elected their own government. This marked the start of separate governments in the Province of North Carolina and the Province of South Carolina. In 1729, the king formally revoked Carolina's colonial charter and established both North Carolina and South Carolina as crown colonies.[112]

In the 1730s, James Oglethorpe, a philanthropist and Member of Parliament, proposed that the area south of the Carolinas be colonized to provide a buffer against Spanish Florida. More importantly for Oglethorpe, the area could serve as a place for impoverished Britons to settle. Parliament granted Oglethorpe and a group of other trustees temporary proprietorship over the Province of Georgia and provided the proprietors with financial support to establish the colony. Oglethorpe and his compatriots hoped to establish a utopian colony that banned slavery and recruited only the most worthy settlers, but by 1750 the colony remained sparsely populated. The proprietors gave up their charter in 1752, at which point Georgia became a crown colony.[113]

Between immigration, the importation of slaves, and natural population growth, the colonial population of Thirteen Colonies grew immensely in the 18th century. According to historian Alan Taylor, the population of the Thirteen Coloneis stood at 1.5 million in 1750, which represented four-fifths of the population of British North America.[114] More than ninety percent of the colonists lived as farmers, though some seaports flourished. By 1760, the cities of Philadelphia, New York, and Boston had a population in excess of 16,000, which was small by European standards.[115] By 1770, the economic output of the Thirteen Colonies made up forty percent of the gross domestic product of the British Empire.[116]

As the 18th century progressed, colonists began to settle far from the Atlantic coast. Pennsylvania, Virginia, Connecticut, and Maryland all lay claim to the land in the Ohio River valley. The colonies engaged in a scramble to purchase land from Native Americans, as the British insisted that claims to land should rest on such acquisitions. Many of these purchases were from tribes with little claim to the land they were selling.[117] Virginia was particularly intent on western expansion, and most of the elite Virginia families invested in the Ohio Company to promote the settlement of Ohio Country.[118]

Global trade and immigration[edit]

With the defeat of the Dutch and the imposition of the Navigation Acts, the British colonies in North America became part of global British trading network. The value of exports from British North America to Britain tripled between 1700 and 1754. Though the colonists were restricted in trading with other European powers, they found profitable trade partners in the other British colonies, particularly in the Caribbean. The colonists traded foodstuffs, wood, tobacco, and various other resources for Asian tea, West Indian coffee, and West Indian sugar, among other items.[119] Native Americans far from the Atlantic coast supplied the Atlantic market with beaver fur and deerskins, and sought to preserve their independence by maintaining a balance of power between the French and English.[120] With an advantage in natural resources, British North America established its own thriving shipbuilding industry and many North American merchants engaged in the transatlantic trade.[121] Wealthy North Americans adopted the opulent Georgian architecture that had become popular in Britain, and many outside of the wealthy elite enjoyed increased material wealth.[122]

Improved economic conditions and an easing of religious persecution in Europe made it more difficult to recruit labor to the colonies. Many colonies, particularly in the South, became increasingly reliant on slave labor. The population of slaves in British North America grew dramatically between 1680 and 1750, and the growth was driven by a mixture of forced immigration and the reproduction of slaves.[123] In the South, the slaves supported vast plantation economies lorded over by increasingly wealthy elites, while slaves in the North worked in a variety of occupations.[124] By 1775, slaves made up one-fifth of the population, though the enslaved proportion of the population int the Middle Colonies and New England was under ten percent.[125] These slaves suffered under worse conditions than those of French and Spanish colonies, and very few were freed; free blacks made up just one percent of the African American population in the 18th century and endured harsh restrictions.[126] The slaves rebelled in major revolts such as the Stono Rebellion and the New York Conspiracy of 1741, but these uprisings were suppressed.[127] The fear of slave revolt softened class divisions among whites while hardening racial divisions.[128]

Though a smaller proportion of the English population migrated to British North America after 1700, the colonies attracted new immigrants from other European countries. These immigrants traveled to all of the colonies, but the Middle Colonies attracted the most immigrants and continued to be more ethically diverse than the other colonies.[129] Despite continuing anti-Catholic settlement, numerous Catholic settlers migrated from Ireland.[130] Protestant Irish also migrated to the colonies, particularly "New Light" Ulster Presbyterians.[131] Protestant Germans also migrated in large numbers, particularly to Pennsylvania, where those of English descent were outnumbered by the other colonists.[132] Many of these immigrants came to despise the established churches that prevailed in nine of the Thirteen Colonies, but a spirit of religious pluralism slowly came into existence during the 18th century. In the 1740s, the Thirteen Colonies underwent the First Great Awakening, which further added to the religious diversity of the Thirteen Colonies.[133]

Conflicts with the French and Spanish[edit]

After the Glorious Revolution, France and England (and its successor state of Britain) engaged in a series of wars, beginning with the Nine Years' War. To win these wars, England drastically expanded the size of its armies and navies. To fund this military expansion, England expanded its administrative state, employing more individuals to collect taxes and duties. As even this expanded administrative state did not provide enough funds to cover the military expenses, England became increasingly reliant on borrowed money.[134] The British desire to pay for the debt incurred in these wars would later provide the spark for the American Revolution.[135]

The Nine Years' War between France and England extended to North America, where it became known as King William's War.[136] In 1689, King Louis XIV of France approved of an expedition from New France designed to crush Iroquois resistance, and the French raided Iroquois and American territory. In retaliation, New York and the New England colonies launched a two-pronged invasion of Quebec which ended in disaster.[137] France and England engaged in a proxy war via Native American allies during and after the war, while the Iroquois declared their neutrality.[138] In Queen Anne's War, the North American component of the War of the Spanish Succession, British colonists again launched a failed expedition capture to Quebec, though British forces did take control of the French town of Port-Royal.[139] In the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of Spanish Succession, the British won possession of the French territories of Newfoundland and Acadia, the latter of which was re-named Nova Scotia.[140]

In 1738, an incident involving a Welsh mariner named Robert Jenkins sparked the War of Jenkins' Ear between Britain and Spain. Hundreds of North Americans volunteered for Admiral Edward Vernon's assault on Cartegena de Indias, a Spanish city in South America.[141] The expedition ended in disaster, but the war against Spain merged into a broader conflict known as the War of the Austrian Succession. In North America, most colonists called the conflict, which also included France, King George's War.[142] In 1745, British and colonial forces led by Vernon captured the town of Louisbourg. The war came to an end with the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, and many colonists were angered when Britain returned Louisbourg to France in return for Madras and other territories.[143] In the aftermath of the war, both the British and French sought to expand their influence among the Native Americans of the Ohio River valley.[144]

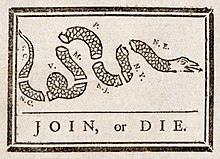

In 1754 the Ohio Company started to build a fort at the confluence of the Allegheny River and the Monongahela River. A larger French force chased the Virginians away but encountered at the Battle of Jumonville Glen, which resulted in a French retreat.[145] After reports of the battle reached the French and British capitals, the Seven Years' War broke out in 1756; the North American component of this war is known as the French and Indian War.[146] At the 1754 Albany Congress, Pennsylvania colonist Benjamin Franklin proposed the Albany Plan of Union, which would have created a unified government of Thirteen Colonies to coordinate defense and other matters. The plan was rejected by the leaders of most colonies and the colonists struggled to coordinate a military response to the French.[147] As the Thirteen Colonies failed to take charge of their own defense, the British dispatched General Edward Braddock to North America to oversee the war effort.[148] Braddock led an expedition into the Ohio country, suffering a rout at the Battle of the Monongahela.[149] British forces suffered further defeats in the following years, losing the Battle of Fort Oswego and the Siege of Fort William Henry.[150]

After the Duke of Newcastle returned to power as Prime Minister in 1757, he shifted British military forces to North America. Newcastle's foreign minister, William Pitt, devoted unprecedented financial resources to the transoceanic conflict.[151] At roughly the same time that Newcastle came to power, the colonists reached accommodation with many of the tribes that had allied with the French. The British won a series of victories after 1758, conquering much of New France by the end of 1760. Spain entered the war on France's side in 1762 and promptly last several territories to Britain.[152] The 1763 Treaty of Paris ended the war, and France surrendered much of New France to the British. Spain ceded Florida to Britain, while France separately ceded its lands west of the Mississippi River to Spain.[153] With the newly acquired territories, the British created the provinces of East Florida, West Florida, and Quebec, all of which were placed under military governments.[154]

Growing dissent, 1763-1774[edit]

The British were saddled with huge debts following the French and Indian War. During the mid-1760s, over half of the British budget was devoted to debt service. Immediately after the war, British colonists in North America paid less than one tenth of the taxes paid by Britons on a per capita basis. As much of the British debt had been generated by the defense of the colonies, British leaders felt that the Thirteen Colonies should pay more in taxes. In the aftermath of the war, the British decided to increase their control over and taxation of the Thirteen Colonies.[155] Beginning with the Sugar Act of 1764, the British imposed several new taxes. Later acts include the Currency Act of 1764, the Stamp Act of 1765, and the Townshend Acts of 1767.[156]

Seeking to avoid another expensive war, the British also sought to maintain peaceful relations with the Indian tribes by keeping them separated from the American frontiersmen.[157] To this end, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 restricted settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, with the area designated as an Indian Reserve.[158] Some groups of settlers disregarded the proclamation, continuing to move west and establish farms. The proclamation was soon modified and was no longer a hindrance to settlement, but the proclamation had nonetheless angered the colonists as it had been promulgated without their prior consultation.[159] Many colonists also thought that the proclamation unfairly rewarded the perpetrators of Pontiac's War, a Native American uprising against the newly-established British rule.[160] The British further incensed the Thirteen Colonies with the Quebec Act, which extended the province of Quebec to the Ohio River. Quebec had been placed under a more authoritarian form of government that tolerated the Catholic faith of its subjects, and many in the Thirteen Colonies continued to view Quebec as a foreign threat.[161]

The British subjects of North America believed that the unwritten British constitution protected their rights, and were firmly devoted to the belief in the superiority of British liberties. They believed that the governmental system, with the House of Commons the House of Lords, and the monarch sharing power found an ideal balance among democracy, oligarchy, and tyranny. The British rarely sent soldiers to North America prior to 1750 and thus were forced to negotiate for colonial support in conducting military operations against the French and the Native Americans. Though royal governors continued to hold a great amount of power in theory, most colonial assemblies gained power over appropriations and the appointment of officials, including sheriffs and judges.[162] Increased British control of the Thirteen Colonies upset the colonists who had had enjoyed their independence, and upended the notion many colonist held that they were equal partners in the British Empire.[163]

Americans insisted on the principle of "no taxation without representation" beginning with the intense protests over the Stamp Act, representation being understood in the context of Parliament directly levying the duty or excise tax, and thus by-passing the colonial legislatures, which had levied taxes on the colonies in the monarch's stead prior to 1763.[164] They argued that the colonies had no representation in the British Parliament, so it was a violation of their rights as Englishmen for taxes to be imposed upon them.[165] In the British colonies bordering the Thirteen Colonies, protests were muted, as most colonists accepted the new tax. These provinces had smaller populations, were more dependent on the British military, and had less of a tradition of self-rule.[166]

In protest of the Townshend Acts, the colonies imposed a boycott of British imports. In 1770, newly installed Prime Minister Lord North repealed the Townshend Acts, with the exception of a a duty on tea. Though some colonists remained upset about the tea tax, most colonists were mollified, and the boycott ended. Colonial discontent resumed with the passage of the 1773 Tea Act, which reduced taxes on tea sold by the East India Company in an effort to undercut smugglers. North's ministry hoped that this would establish a precedent of colonists accepting British taxation policies. In 1773, a secret society known as the Sons of Liberty dumped thousands of pounds of tea into the water, in event known as the Boston Tea Party. The event outraged members of Parliament, many of whom felt that they had attempted to reach a compromise with the Thirteen Colonies by repealing the Townshend Acts. In 1774, Parliament the Coercive Acts, which became known as the "Intolerable Acts" in the colonies. These laws allowed British military commanders to claim colonial homes for the quartering of soldiers, transferred trials involving soldiers or crown officials outside of the jurisdiction of the colonists, and reformed the government of Massachusetts. Parliament also sent Thomas Gage to serve as Governor of Massachusetts and as the commander of British forces in North America.[167]

By 1774, most colonists still hoped to remain part of the British Empire, but discontent at British rule was widespread.[168] Throughout the Thirteen Colonies, colonists elected delegates to the First Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia in September 1774. In the aftermath of the Intolerable Acts, the delegates of the First Continental Congress asserted that the colonies only owed allegiance to the king. They would accept royal governors as agents of the king, but they were no longer willing to recognize Parliament's right to pass legislation affecting the colonies. Most delegates opposed an attack on the British position in Boston, and the Continental Congress instead agreed to the imposition of another boycott, known as the Continental Association. The boycott proved effective and the value of British imports dropped dramatically.[169] The Thirteen Colonies became increasingly divided between Patriots opposed to British rule and Loyalists who supported it.[170]

American Revolution[edit]

Fearing an impending conflict, Gage requested reinforcements from Britain, but the British government was not willing to pay for the expense of stationing tens of thousands of soldiers in the Thirteen Colonies. Gage was instead ordered to seize Patriot arsenals. He dispatched a force to march on the arsenal at Concord, Massachusetts, but the Patriots learned about this troop movement and sought to block their advance. The Patriots repulsed the British force at the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, then lay siege to Boston.[171] The Second Continental Congress assembled in May 1775 and sought to coordinate armed resistance to Britain. It established an impromptu government that recruited soldiers and printed its own money. George Washington, a Virginian who had fought in the French and Indian War, was selected to lead the newly established Continental Army.[172] Washington took command of rebel soldiers in New England and forced the British soldiers to withdraw from the city. The war spread into new theaters, and the Thirteen Colonies launched a failed invasion of Quebec.[173]

By 1775, some delegates wanted to fully sever ties with Britain, but most still saw the king as their legitimate ruler.[174] However, King George III refused to read the Continental Congress's Olive Branch Petition, which beseeched the king to broker a cease fire. He instead proclaimed the colonists to be in rebellion in August 1775.[175] In January 1776, Thomas Paine published Common Sense, a pamphlet advocating independence from Britain and the establishment of republican governments in each of the Thirteen Colonies. The pamphlet mobilized popular support for independence, and the delegates of the Second Continental Congress became increasingly willing to consider independence.[176] Seeking a final break with Britain, the delegates adopted a Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.[177] Though they feared dependence on another foreign power, the delegates dispatched ambassadors to seek French and Spanish aid in the war against Britain.[178]

In the 1776 New York and New Jersey campaign, General William Howe led a British army that drove Washington's army from New York City into Pennsylvania.[179] Washington rallied his army after retreating across the Delaware River, and his victory at the Battle of Trenton significantly boosted Patriot morale.[180] In 1777, the British pursued two major campaigns, with the force led by Howe marching on Philadelphia in the Philadelphia campaign, and a force stationed in Quebec and led by John Burgoyne seeking to take control of the Hudson River in the Saratoga campaign.[181] With the aid of reinforcements sent by Washington, General Horatio Gates led the Continental Army to victory at the Battles of Saratoga, forcing Burgoyne's surrender.[182] Howe captured Philadelphia after the September 1777 Battle of Brandywine, forcing Congress temporarily relocate its meeting place.[183]

Following the American victory at the Battle Saratoga, the French became convinced that the Americans could defeat the British. The French entered the war and French and American representatives signed the Treaty of Alliance, in which both parties agreed not to seek a separate peace. In hopes of gaining back their former territories, especially Gibraltar, the Spanish entered the war in 1779. The British sought their own European alliance to counter-balance the French and Spanish, but British success in the Seven Years' War had left the British too powerful in the view of the other European powers. Instead, these powers created the League of Armed Neutrality to defy the British attempts to blockade trade. The British faced a global war without allies, and were forced to divert soldiers from North America. Now in a tenuous position, Prime Minister North sent the Carlisle Peace Commission to offer to rescind the Coercive Acts and accept Congress as a legitimate legislature under the authority of the crown, but Congress rejected any reincorporation into the British Empire.[184] By the end of 1781, each of the colonies had ratified a constitution for a new nation, known as the Articles of Confederation. The Articles provided for a decentralized confederation of state governments and a weak national government.[185] The first article of the new constitution established a name for the former Thirteen Colonies: the United States of America.[186]

In order to consolidate British forces, the British retreated from Philadelphia back to New York. The war in the north became a stalemate, as the British conducted no major campaigns and Washington did not attempt to capture the British position in New York.[187] The British shifted their focus to the southern theater of the war, where they hoped to recruit Native American and Loyalist allies. British forces captured Savannah, Georgia in December 1778 and consolidated their control over Georgia in the following months.[188] The British captured Charleston in May 1780 and engaged in several operations in North Carolina and Virginia under General Charles Cornwallis. In April 1781, Cornwallis led his army into Virginia in the Yorktown campaign, seeking to force a decisive battle.[189] Despite the string of British victories starting 1778, Patriot forces under Nathanael Greene resisted British rule, and the British were unable to exercise effective authority over the hinterland of Virginia and the Carolinas.[190] A combined Franco-American operation trapped Cornwallis's force at Yorktown, and Washington led his men in a hurried march from New York to Virginia. He laid siege to Yorktown, forcing Cornwallis's surrender in October 1781.[191] His force had made up one quarter of the British force in North America, and conflicts in other theaters meant that the British were unable to replace those forces. The surrender shocked Britons, who lost the public will to continue the war in North America, and the British opened peace negotiations.[192]

In the negotiations leading to a peace deal, the Patriots hoped to gain control of all of the British territories on the continent of North America, though their actual control was confined to the Thirteen Colonies, parts of which remained occupied by the British. The French hoped to keep the United States as a weak client state, while the Spanish feared the rise of an expansive empire bordering their colonial holdings, so both sought to limit American gains in a treaty with the British. The British Prime Minister, Lord Shelburne, hoped to reconcile with the United States and reestablish trade relations.[193] The British offered generous terms to the United States if they agreed to seek a separate peace from France. In the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the United States won control of all British North American territory south of the Great Lakes, except for the two Florida colonies. Though Parliament ratified the treaty, discontent at its generosity to the United States led to the fall of Lord Shelburne's government and the defeat of a proposed commercial treaty between the United States and Britain.[194]

See also[edit]

- America's Critical Period

- Atlantic history

- British colonization of the Americas

- Colonial American military history

References[edit]

- ^ Richter, pp. 69-70

- ^ Richter, pp. 82-83, 97

- ^ Richter, pp. 83-85

- ^ Richter, pp. 121-123, 128-129

- ^ Richter, pp. 129-130

- ^ Richter, pp. 140-141

- ^ Richter, pp. 98-100

- ^ Richter, pp. 100-102

- ^ Richter, pp. 103-107

- ^ Richter, p. 112

- ^ Richter, pp. 113-115

- ^ Richter, p. 117

- ^ Richter, pp. 113-115

- ^ Richter, pp. 116-117

- ^ Richter, pp. 203-204

- ^ Richter, pp. 152-153

- ^ Richter, pp. 178-179

- ^ Richter, pp. 153-157

- ^ Richter, pp. 138-140

- ^ Richter, pp. 159-160

- ^ Richter pp. 212-213

- ^ Richter pp. 214-215

- ^ Richter pp. 213-214

- ^ Richter pp. 215-217

- ^ Richter, p. 150

- ^ Richter p. 213

- ^ Richter, p. 262

- ^ Richter pp. 247-248

- ^ Richter, pp. 248-249

- ^ Richter, p. 249

- ^ Richter p. 261

- ^ Richter, pp. 130-131

- ^ Richter, pp. 134-135

- ^ Richter pp. 217-220

- ^ Richter pp. 257-258

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 17

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 39

- ^ Richter, pp. 143-144

- ^ Richter, pp. 145-147

- ^ Richter, pp. 147-151

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 39-40

- ^ The year the colony was first settled or established.

- ^ a b c d e f g Virginia became a crown colony in 1624. In 1691, Massachusetts Bay Colony and Plymouth Colony were incorporated into the Province of Massachusetts Bay, which was a crown colony. New York also became a crown colony in 1691. Georgia became a crown colony in 1755.

- ^ Maryland became a royal colony in 1691.

- ^ a b Saybrook and New Haven were incorporated into Connecticut Colony in the 17th century

- ^ Richter, pp. 262-263

- ^ Richter, pp. 203-204

- ^ Richter, pp. 303-304

- ^ Richter, p. 265

- ^ Richter, pp. 205-206

- ^ Richter, pp. 210-211

- ^ Richter, p. 272

- ^ Richter, pp. 209-210

- ^ Richter, pp. 266-271

- ^ Richter, pp. 273-275

- ^ Richter, pp. 277-278

- ^ Richter pp. 221-224

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 12-13

- ^ Richter, pp. 236-238

- ^ Richter, p. 319

- ^ Richter, pp. 322-323

- ^ Richter, pp. 157-159

- ^ Richter, pp. 161-167

- ^ Richter, p. 167

- ^ Richter, p. 168

- ^ Richter, p. 168

- ^ Richter, pp. 196-197

- ^ Richter, pp. 193-194

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 19

- ^ Richter, pp. 254-255

- ^ Richter, pp. 261-262

- ^ Richter, p. 312

- ^ Richter, pp. 314-315

- ^ Richter, pp. 247-249

- ^ Richter, pp. 249-251

- ^ Richter, pp. 252-253

- ^ Richter, pp. 287-288

- ^ Ricther, p. 373

- ^ Richter, p. 251

- ^ Richter, pp. 357

- ^ Richter, pp. 358

- ^ Richter, pp. 283-285

- ^ Richter, pp. 283-287

- ^ Richter, pp. 283-287

- ^ Richter, pp. 290-294

- ^ Richter, pp. 303

- ^ Richter, pp. 300-301

- ^ Richter, pp. 310-311, 328

- ^ Richter, pp. 312-313

- ^ Richter, pp. 313-314

- ^ Richter, pp. 314-315

- ^ Richter, p. 315

- ^ Richter, pp. 315-316

- ^ Richter, p. 172

- ^ Richter, p. 173

- ^ Richter, pp. 173-174

- ^ Richter, p. 174

- ^ Richter, pp. 174-175

- ^ Richter, pp. 175-177

- ^ Richter, pp. 178-183

- ^ Richter, pp. 184-185

- ^ Richter pp. 234-235

- ^ Richter p. 235

- ^ Richter pp. 246-247

- ^ Richter, pp. 242-246

- ^ Richter, pp. 291-294

- ^ Richter, pp. 296-298

- ^ Richter, pp. 317-318

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 12-13

- ^ Richter, pp. 338-339

- ^ Richter, pp. 319-322

- ^ Richter, pp. 323-324

- ^ Richter, pp. 358-359

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 20

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 23

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 25

- ^ Richter, pp. 373-374

- ^ Richter, pp. 376-377

- ^ Richter, pp. 329-330

- ^ Richter, pp. 332-336

- ^ Richter, pp. 330-331

- ^ Richter, pp. 339-342

- ^ Richter, pp. 346-347

- ^ Richter, pp. 351-352

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 21

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 21

- ^ Richter, pp. 353-354

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 22

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 18-19

- ^ Richter, pp. 360

- ^ Richter, pp. 361

- ^ Richter, pp. 362

- ^ Middlekauff, pp. 46-49

- ^ Middlekauff, pp. 23-26

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 51-53

- ^ Richter, pp. 317-318

- ^ Richter, pp. 311-312

- ^ Richter, pp. 317-318

- ^ Richter, pp. 318-319

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 19

- ^ Richter, pp. 345

- ^ Richter, pp. 379-380

- ^ Richter, pp. 380-381

- ^ Richter, pp. 383-385

- ^ Richter, pp. 385-387

- ^ Richter, pp. 388-389

- ^ Richter, pp. 390-391

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 43-44

- ^ Richter, pp. 391-392

- ^ Richter, pp. 394-395

- ^ Taylor (2016), p. 45

- ^ Richter, pp. 396-398

- ^ Richter, pp. 406-407

- ^ Richter, pp. 407-409

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 51-53

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 94-96, 107

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 60-61

- ^ Colin G. Calloway, The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America (2006), pp 92–98

- ^ Woody Holton, "The Ohio Indians and the coming of the American revolution in Virginia", Journal of Southern History, (1994) 60#3 pp. 453–78

- ^ Richter, pp. 407-409

- ^ Taylor (2016) pp. 84-86

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 31-35

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 51-52

- ^ J. R. Pole, Political Representation in England and the Origins of the American Republic (London; Melbourne: Macmillan, 1966), 31, http://www.questia.com/read/89805613.

- ^ Meinig, p. 315

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 102-103

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 112-114

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 137-121

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 123-127

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 137-138

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 132-133

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 139-141

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 151-154

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 139-141

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 144-145

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 155-159

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 160-161

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 175-177

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 162-167

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 171-173

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 178-179

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 180-182

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 182-183

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 187-191

- ^ Ferling (2003), pp. 177-179, 230-232

- ^ Chandler, p. 434

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 191-194

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 226-230

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 234-243

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 243-247

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 293-295

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 295-297

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 303-304

- ^ Taylor (2016), pp. 306-308

Works cited[edit]

- Chandler, Ralph Clark (Winter 1990). "Public Administration Under the Articles of Confederation". Public Administration Quarterly. 13 (4): 433–450.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press.

- Middlekauf, Robert (2005). The Glorious Cause: the American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press.

- Meinig, Donald William (1986). The Shaping of America: Atlantic America, 1492-1800. Yale University Press.

- Richter, Daniel (2011). Before the Revolution : America's ancient pasts. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press.

- Taylor, Alan (2016). American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. W. W. Norton & Company.

Further reading[edit]

- Bailyn, Bernard (2012). The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America--The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675. Knopf.

- Berlin, Ira (1998). Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America. Belknap Press.

- Breen, T.H.; Hall, Timothy (2016). Colonial America in an Atlantic World (2nd ed.). Pearson.

- Canny, Nicholas (1998). The Origins of Empire: British Overseas Enterprise to the Close of the Seventeenth Century. Oxford University Press.

- Carr, J. Revell (2008). Seeds of Discontent: The Deep Roots of the American Revolution, 1650-1750. Walker Books.

- Cooke, Jacob Ernest et al., ed. Encyclopedia of the North American Colonies. (3 vol. 1993); 2397 pp.; comprehensive coverage; compares British, French, Spanish & Dutch colonies

- Elliott, John (2006). Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830. Yale University Press.

- Games, Alison (2008). The Web of Empire: English Cosmopolitans in an Age of Expansion, 1560-1660. Oxford University Press.

- Gaskill, Malcolm (2014). Between Two Worlds: How the English Became Americans. Basic Books.

- Gipson, Lawrence. The British Empire Before the American Revolution (15 volumes, 1936–1970), Pulitzer Prize; highly detailed discussion of every British colony in the New World

- Horn, James (2005). A Land As God Made It: Jamestown and the Birth of America. Basic Books.

- Lepore, Jill (1999). The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity. Vintage.

- Mann, Charles C. (2011). 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. Knopf.

- Middleton, Richard; Lombard, Anne (2011). Colonial America: A History to 1763 (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Shorto, Russell (2004). The Island at the Center of the World: The Epic Story of Dutch Manhattan and the Forgotten Colony that Shaped America. Doubleday.

- Taylor, Alan (2002). American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin Books.

- Weidensaul, Scott (2012). The First Frontier: The Forgotten History of Struggle, Savagery, and Endurance in Early America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

External links[edit]

Media related to Orser67/Thirteen Colonies at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Orser67/Thirteen Colonies at Wikimedia Commons