User:Kew Gardens 613/sandbox 13

The Staten Island Railway (SIR) is the only rapid transit line in the New York City borough of Staten Island and is operated by the Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority, a unit of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The railway is considered a standard railroad line, but only the western portion of the North Shore Branch, which is disconnected from the rest of the SIR, is used by freight and is connected to the national railway system.

While the first rail proposal for rail service on Staten Island was issued in 1836, construction did not begin until 1855 after the project was attempted a second time under the name Staten Island Railroad. This attempt was successful due to the financial backing of William Vanderbilt. The line opened in 1860 and ran from Tottenville to Vanderbilt's Landing and connected with ferries to Perth Amboy, New Jersey and New York, respectively. After the Westfield ferry disaster at Whitehall Street Terminal in 1871, the railroad went into receivership and was reorganized into the Staten Island Railway Company in 1873. In the 1880s, Erastus Wiman planned a system of rail lines encircling the island using a portion of the existing rail line, and organized the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad in 1880, in cooperation with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O), which wanted an entry into New York. B&O gained a majority stake in the line in 1885, and by 1890 new extensions to the line were in service. In 1890, the Arthur Kill Bridge opened, connecting the island to New Jersey. This route proved to be a major freight corridor. After a period of financial turmoil in the 1890s which saw both B&O and the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad company enter bankruptcy, the railroad was restructured as the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway (SIRT), and was purchased by the B&O in 1899.

In 1924, SIRT began electrification of its lines, to comply with the Kaufman Act, which had become law the previous year. New train cars, designed to be compatible with subway service, were ordered, and electric service was inaugurated on the system's three branches in 1925. Through the 1930s and 1940s grade-crossing elimination projects were completed on the three branches. During World War II, freight traffic on the SIRT increased dramatically, briefly making it profitable. In 1948, the New York City Board of Transportation took over all of the bus lines on Staten Island, resulting in a decrease in bus fares from five cents per zone to seven cents for the whole island. Riders of the SIRT flocked to the buses, resulting in a steep drop in ridership. Service on the branches was subsequently reduced. In 1953 the SIRT discontinued service on the North Shore Branch and South Beach Branch. The South Beach Branch was abandoned shortly thereafter while the North Shore Branch continued to carry freight. While the SIRT threatened to discontinue service on the Tottenville Branch, the service was preserved as New York City stepped in to subsidize the operation. In 1971 New York City purchased the Tottenville line, and the line's operation was turned over to the Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority, a division of the state-operated Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Freight service continued until 1991.

Improvements were made under MTA operations. The line received its first new train cars since the 1920s, and several stations were renovated. The MTA rebranded the Staten Island Rapid Transit as the MTA Staten Island Railway (SIR) in 1994. Fares on the line between Tompkinsville and Tottenville were eliminated in 1997 with the introduction of the MetroCard. In 2010 fare collection was reintroduced at Tompkinsville. A new station on the main line, Arthur Kill, opened, replacing the deteriorated Nassau and Atlantic stations. It was the first new station opened on the main line in seventy years. While the railway does not serve residents on the western or northern sides of the borough, light rail and bus rapid transit have been proposed for these corridors. Freight service in northwestern Staten Island was restored in the 2000s.

Corporate history[edit]

| Years | Company | Abbreviation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1836-1838 | Staten Island Rail-Road Company | Failed attempt to build the railway.[1]: 1253 | |

| 1851-1873 | Staten Island Railroad Company | SIRR | Created by Vanderbilt in 1851; was sold to Law 1872, and then sold to the Staten Island Railway Company in 1873.[1]: 1254–1255 |

| 1873-1884 | Staten Island Railway Company | SIRW | Created to assume operations of the SIRR, and was leased by the SIRTR in 1884. It continued to operate as a separate company.[1]: 1255–1257 |

| 1880-1899 | Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad Company | SIRTR | Created to build extensions; was sold to the SIRT in 1899.[1]: 1257–1260 |

| 1899-1971 | Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway Company | SIRT | Created to operate the SIRTR;[1]: 1260 was sold by the B&O to the MTA in 1971.

Was commonly known as the SIRT.[2] |

| 1971–present | Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority | SIRTOA | Created in 1971 to transfer operations of the SIRT from the B&O to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA);[2] publicly known as MTA Staten Island Railway (SIR) since 1994.[3] |

First line: 1836–1885[edit]

Initial efforts: 1836–1860[edit]

First attempt: 1836[edit]

The need for a railroad on Staten Island originated from the need for better ways for the island's farmers to trade. The island was used mainly for agriculture, with 85% of its land dedicated for this purpose–mainly on the south shore, east shore and the center of the island. Many farmers traded with other farmers and tradesman in New Jersey–specifically Perth Amboy across the Arthur Kill.[4]: 5–6 The island's transportation was inadequate, with the existence of only a few main roads, which were difficult to traverse. In addition, it was hard for farmers to access Cornelius "Commodore" Vanderbilt's ferries, which carried a lot of trade. His ferries ran between Vanderbilt's Landing and Whitehall in Manhattan and Brooklyn, which he started in the early 1800s, and ferries to New Brunswick, New Jersey, which started earlier on. To the farmers of Perth Amboy and Staten Island, it became clear that better transportation was needed to make a profit and to take advantage of the ferries, by providing better transportation across the island, and a link to markets in Long Island, Manhattan and New Jersey. Some businessmen and farmers had become aware of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's (B&O) experimental use of a steam locomotive hauling passengers and freight in Maryland.[4]: 7–8 The construction of a railroad was deemed the best option, and prominent farmers and businessmen applied to the New York State Legislature for a charter to build a single or double-tracked line "commencing at some point in the town of Southfield, within one mile of the steamboat landing at the Quarantine, and terminating at some point in the town of Westfield; opposite Amboy." They incorporated the Staten Island Rail-Road Company on May 21, 1836, and a five-person board of directors was elected. The proposed line would have run between the present-day locations of Clifton and Tottenville.[5]: 7 [6]: 225 [7]: 4 The 13-mile (21 km) route had an estimated cost of $300,000.[8]: 687 However, the company lost its charter in 1838 because the railroad was not built within two years after it was incorporated.[1]: 1253–1254 It is unclear why the railroad was not built.[4]: 8–9

Second attempt: 1851[edit]

Attempts to start a rail line on the island were restarted in 1849 and 1850, when residents of Perth Amboy and Staten Island held meetings concerning a possible Tottenville-to-Stapleton line. Like the previous attempt in 1836, they faced financial difficulties, and sought out the help of William Vanderbilt—a son of Cornelius Vanderbilt and a resident of Staten Island. Vanderbilt had conceived of such a railroad as a way to reduce the monopoly of the Camden and Amboy Railroad, which was the only mean of reaching Philadelphia. Passengers would take ferries from New York City to Amboy, the railroad to Camden, and finally a ferry to Philadelphia. Vanderbilt thought his railroad would cut travel times—passengers would take a ferry from New York to Staten Island, then take his railroad, before taking a ferry to Amboy—and eliminate the monopoly of the Camden and Amboy between New York City and its terminus in Amboy.[9] Since the plan conceived by the local residents followed Vanderbilt's proposed route, he helped charter the Staten Island Railroad Company (SIRR) on August 2, 1851 in order to build the rail line. The articles of association for the company were filed on October 18, 1851.[10]: 27–28 The company's capital stock consisted of $300,000, and had 13 members on its Board of Directors. The company's president was Joseph Seguine. The railroad's charter lasted for fifty years and was renewable if physical construction of the road did not immediately start. Subscribers who bought the company's stock did not pay for them right away, delaying the line's construction by two years.[4]: 11–12 Like the previous attempt, the line has two years to be built. To prevent the loss of the line's charter, in 1853, the company successfully petitioned for a two-year extension to build the line. In 1853, a bill giving the company the right to operate ferries was passed,[11][12] authorizing it to operate ferries from the island's east shore to Manhattan and between Perth Amboy and Tottenville.[4]: 13–14

On March 27, 1852, J.B. Bacon, a resident engineer submitted a report to the Board of Directors concerning the railroad's planned route and the cost of construction. He expected the line to cost $322,195. Two possible route options were considered; the first would start at New Ferry Dock in Stapleton, before passing through Rocky Hollow, following the valley between Castleton and Southfield Heights before descending to New Dorp. After going 4 miles (6.4 km) through the valley, the line would curve toward Amboy Road before curving southward, passing Billop House, and ending near Biddle's Grove and the Amboy ferries. The second route would start at Vanderbilt's Landing and run through Clifton to New Dorp.[10]: 14–16

In January 1855 the company applied to the New York State Legislature for a three-year extension to complete the project. After all of the property required for the right-of-way was acquired, construction commenced in November 1855.[5]: 7 [1]: 1254–1255 [13]: 444

Like the original plan for the line, difficulties were encountered. Bad weather, hard terrain, obtaining capital and acquiring property for the line's right-of-way delayed the line.[4]: 14 The railroad's Board of Directors hired civil engineer Oliver H. Lee to survey routes for the line. Many property owners refused to sell their land, blocking the proposed line. His report, issued on August 21, 1855, called for the construction of a line from either Vanderbilt's Landing to Tottenville (13.5 miles (21.7 km)) or Stapelton to Tottenville (14.25 miles (22.93 km)). The line's right-of-way was sited to be convenient to the settlements on the island's northwest shore and its interior. It was to start "on the north or west side of the residence of Stephen Seguine, Esq. and continue it on the north side of the Amboy Road, to a point beyond the church, the line then follows a natural valley formation to the shore, passing through the village of Tottenville, and terminating at the dock opposite South Amboy, and immediately opposite the depot of the Camden and Amboy Railroad Corporation." The road bed's width was to be 12 feet (3.7 m) on embankments, and 18 feet (5.5 m) in excavation. Farm crossings and cattle guards were to be installed for protection. The line's cost without right-of-way was estimated to be $225,772, of which $27,200 was for the cost of equipment. The proposed schedule for the line was six daily trains each way for half the year, and four daily trains during the rest of the year, running six days a week, with an annual operating cost of $26,020. He saw the line as a direct link between New York and Philadelphia and anticipated increases in real estate values on both sides of the Hudson River.[4]: 15–18

The report was adopted, and work started immediately, with the groundbreaking taking place near present-day Bay Terrace in November. The company, however, had run out of money to complete the line, halting progress. The railroad asked Cornelius Vanderbilt—the sole Staten Island-to-Manhattan ferry operator—for a loan.[4]: 19–20 [7]: 4 Vanderbilt was weary of the railroad's prospects for success, and was worried that its ferries would end his ferry monopoly. Vanderbilt tried to stop competitors who had obtained a lease for the ferry at Vanderbilt's Landing before he could get a lease. He hired James R. Robinson to build a building to block his competitors from building a second ferry competing with his. On July 28, 1851, a group of farmers and stockholders in support of the railroad deconstructed the almost-finished structure with picks and axes and threatened to hurt Robinson if he tried to block them.[7]: 4 [4]: 20–21 Vanderbilt accepted that the railroad was going to be built, and agreed to finance the railroad[6]: 225 if the northern terminal of the line was moved from Stapleton to a point no further than his ferry landing Vanderbilt's Landing further east.[14]: 461 This move made it impossible for the railroad to control new ferry lines beyond Vanderbilt's Landing, and as it was easier to get a ferry to New York City or Brooklyn from Stapleton than from Clifton.[4]: 21 In 1858, William Vanderbilt was inducted onto the railroad's board of directors.[5]: 7 Construction of the line was completed as far as a village between Old Town and Eltingville by early 1860.[4]: 22

Opening: 1860[edit]

Stockholders and officials took an inaugural ride on the double-track line between Vanderbilt's Landing and Eltingville on February 1, 1860, and passenger operations began on April 23 that year,[6]: 225 [7]: 4 [15][16] with the first train leaving from Eltingville. Local residents were more interested in the locomotive than the opening of the line.[4]: 24 The initial timetable called for service every day except Sunday leaving Eltingville at 7:15 and 10 a.m. and 5 p.m. in time for the 8 a.m., 11 a.m. and 6 p.m. boats leaving from Vanderbilt's Landing to New York. Return trips left upon the arrival of the 8 a.m., and 3 and 5 p.m. boats. On Sunday trains left Eltingville at 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. in time for the 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. boats, and trains left Vanderbilt's Landing upon the arrival of the 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. boats. Trains initially made intermediate stops at Toad Hill, New Dorp, Harrison's Club House and Gifford's Lane.[4]: 24 [17] The first locomotive was named "Albert Journeay", after the railroad's president. A second locomotive was added to the line on May 5, 1860; it was named "E. Bancker" after the company's vice-president.[18] Both were purchased from the Jersey City Railway Works.[4]: 22 The remainder of the line was expected to be completed in a month.[16]

Over the next month, the remainder of the line was built between Annadale and Pleasant Plains as a single-track line, with a passing siding at Huguenot, passing through mosquito-infested land laced with peat bogs and quicksand—an area known locally as Skunk's Misery. It took a lot of time and wood to built the sub-roadbed with logs. It was viewed as unlikely to be a worthwhile investment to double-track the line because of the low passenger volume south of New Dorp. South of Pleasant Plains, the line was double-tracked.[18] The line was extended to Annadale on May 14, 1860, and was completed to Tottenville on June 2 (12?)[4]: 24 , 1860, with a formal opening of the railroad.[7]: 5 [19] The completion of the line to Tottenville allowed passengers to transfer to a ferry that crossed the Arthur Kill and allowed passage to Perth Amboy, New Jersey.[5]: 7 [6]: 225 [20]: 36 Services made eleven stops between Vanderbilt's Landing and Tottenville.[21] Many stations were named after nearby large farms, such as Garretson's and Gifford's. The stations built at Eltingville and Annadale—whose namesakes, the Eltings family and Anna Seguine, were influential in paying for the construction of the rail line—were the most elaborate.[18] The arrival of the railroad gave dignity to some locations on Staten Island; "Poverty Hollow" was renamed Rosebank, Oakwood became Oakwood Heights, and other places were renamed with the coming of the railroad.[22] On October 5, 1861, in what might have been the first major accident on the railroad, Mary Austin, age 16, was killed by a train at Princess Bay as she crossed the tracks.[23]

In August 1860, the railroad was extended from the depot at Vanderbilt's Landing to the wharf, allowing passengers to walk directly to the boat from the train instead of walking 100 feet (30 m) along the sand. At the time, it took one and a half hours to get to Tottenville from Manhattan. At the time, patronage of the rail line exceeded the greatest expectations of its projectors.[21] However, ridership did not continue this trend, and debts piled up, forcing the railroad to declare bankruptcy in February 1861. On February 27, 1861, the Jersey City Locomotive Works gave notice of foreclosure on the two locomotives. The Board of Directors appealed to Cornelius Vanderbilt, and on September 4, 1861, he placed the SIRR into receivership with his son William to prevent the loss of the locomotives and rolling stock to creditors, keeping the locomotives on Staten Island.[4]: 25–26 [5]: 7 [6]: 225 [7]: 5

William Vanderbilt saw the cause of the railroad's financial difficulties as mismanagement and the lack of priorities in its plannings. For instance, there was no coordination between the arrival of the train and the departure of attorney George Law's ferryboats, despite the statements of the timetable, especially at Vanderbilt's Landing. Boats would sometimes leave before the train had arrived there, or would sometimes land at Tompkinsville instead, forcing passengers to walk almost 1 mile (1.6 km) to get to Vanderbilt's Landing, missing their train in the process. The coordination between the two modes was solved by 1864, and the interiors of station depots and the trains were improved with additional capital from the Vanderbilts. The company's financial stock increased as ridership increased.[4]: 27–28 The Vanderbilts had taken stock in the railroad but in 1863, and William managed the receivership well enough for it to be discharged, with the debt paid off. As a result, the railroad became property of the Vanderbilts; facilities were enlarged under their leadership—an expansion made possible by increasing the capital stock to $800,000 from $350,000.[9] The railroad remained solvent as long as the Vanderbilt family ran the railroad.[4]: 26

Ferry conflicts: 1860–1884[edit]

In 1863, SIRR-operated ferry service began between Perth Amboy and Tottenville in 1863.[24] Vanderbilt tried to operate a ferry service between Manhattan and Staten Island that would compete with Law's. He also started construction on a central dock on the island, but he abandoned the scheme after a storm destroyed the timber work. Only the large stone foundation remained; it was still visible at low tide in 1900.[14]: 462 Vanderbilt was eventually forced to sell his ferry service to Law after a franchise battle.[6]: 226 After the battle, he lost interest in transit operations on Staten Island and handed the ferry and railroad operations to his brother Jacob H. Vanderbilt, who was the company's president until 1883.[5]: 7 [14]: 462 [18] In March 1864, William Vanderbilt bought Law's ferries, bringing both the railroad and the ferries under the same company.[6]: 226 In 1865, the railroad took over operation of the New York & Richmond Ferry Company, and would later assume direct responsibility for operating the ferry service to Manhattan.[5]: 7 The Perth Amboy and Staten Island ferries were taken over by the railroad under the leadership of Jacob Vanderbilt.[18]

The SIRR and its ferry line were making a modest profit until the boiler of the ferry "Westfield" exploded at Whitehall Street Terminal on July 30, 1871, killing (66?) 85 and injuring hundreds.[5]: 7 [6]: 226 Jacob Vanderbilt was arrested, as president of the railway, but was not charged.[25]: 101 Ridership on the railroad significantly decreased with riders not wanting to use a railroad that was responsible for the deaths of 66? people. As a result, the railroad and ferry went into receivership on March 28, 1872.[6]: 228 [26]: 553 On September 17, the property of the company was sold by William H. Vanderbilt's successor, L.H. Meyer in foreclosure to George Law ,[4]: 28–29 [6]: 228 with the exception of the ferry "Westfield", which was purchased by Horace Theall.[7]: 5 [14]: 462

Some time after, Law and Theall sold the SIRR and ferry to the Staten Island Railway Company (SIRW). Law had threatened to form a company of his own if the stockholders did not come to his terms promptly, but a deal was reached. The charter for the SIRW was created on March 20, 1873, and on April 1, 1873, Law transferred the SIRR's property to the SIRW for $480,000.[1]: 1255 [14]: 462 [18][27]: 569 Despite the change in the name of the railroad, which was changed for publicity purposes,[4]: 29 the stockholders and property were maintained. The ferry operation was split off to the newly formed Staten Island Railway Ferry Company, to prevent problems with one from leading to the demise of the other, while ensuring that connecting service could still be provided for passengers.[24] Until 1881, the company remained viable, but was not as successful as anticipated prior the line's opening.[4]: 29

During the American Civil War, a boat connected with the SIRW, the "Southfield", was sold to the Federal Government and converted into a gunboat; it was destroyed during an attack on Mississippi. In 1876, Commodore Garner obtained posession of a ferry and ran the "D. R. Martin" to the island's east shore, competing with the SIRW's ferries. After he died, the ferry service ended, and his boats were purchased by John Starin, who obtained a franchise and paid $5,000 for each of theme. He operated it until the lease was taken over by the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad Company (SIRTR) on August 1, 1884.[14]: 462 [28]: 70

SIRT/B&O operation: 1880–1900[edit]

Organization: 1880–1884[edit]

By 1880, the SIRW was barely operational, and New York State Attorney General Hamilton Ward sued to have the company dissolved in May that year. The suit stated that the company had become "insolvent in September 1872, to have then surrendered its rights to others, and have failed to exercise those rights". The legal proceedings commenced after an injunction was obtained, restraining the creditors of the railway company from proceeding against it until the outcome of the suit was determined.[6]: 229 [29] Although the line was not doing well, it became the centerpiece of a plan to develop the island by Canadian entrepreneur Erastus Wiman. In 1867, he arrived in New York as a journalist for Dun, Barlow, and Company, before later overseing its main office.[4]: 32 [20]: 36 Wiman became one of the most prominent residents of Staten Island after moving into a mansion. He was dubbed the "Duke of Staten Island," and was interested in developing the island. Wiman recognized that to succeed he would need to build a coordinated transportation hub with connections to New York City and New Jersey.[6]: 230 [20]: 37

Wiman noticed the inadequacies of the rail system and concluded that rail lines should be built along the north and east shores of the island.[4]: 33 He contacted other wealthy people interested in building other rail lines on the island, with many supporting him. To obtain the necessary capital, he went to the B&O Railroad, whose acting president, Robert Garrett, wished to expand his system to the northeast United States, which was dominated by the New York Central Railroad (NYCRR) and the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR). Through various contacts, Wiman approached him and proposed that the B&O fund the project. Wiman told him that if funded, the project would be allowed to use the North Shore Branch to move freight from St. George to New Jersey, giving it its long-desired freight terminus in New York, allowing it to enter the Atlantic freight market. The idea was approved by the B&O's Board of Directors.[5] : 7 The plan faced several hurdles, including approval by the New York State Legislature, and the B&O's limited lines in New Jersey. The B&O did not have any lines immediately opposite Staten Island in New Jersey, and a bridge spanning the Arthur Kill would be required, involving the legislatures of both states, the Federal Government, and requiring permission from the Jersey Central Railroad. The B&O did not put up any capital for five years, requiring Wiman to build the line.[4]: 33–37 To this end, the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railroad Company (SIRTR) was organized on March 25, 1880[27]: 569 with a capital stock of $500,000, and the line's articles of association were filed by Wiman and 15 other stockholders on April 13, 1880.[1]: 1257 The inclusion of Rapid Transit in the company's name makes clear that Wiman was aware of the rapid transit improvements made on Long Island and in Manhattan, and that he sought to improve transportation access to the most populated areas in need of it.[4]: 37–38

Wiman's plan called for a system encircling the island, an extension of the SIRW's line from Vanderbilt's Landing to Tompkinsville, and the centralization of all ferries from one terminal, replacing the six to eight terminals active near what is now St. George. The line was to begin on the island's east shore near New Dorp Lane and Peterlers South Beach Pavilion, running in the most direct manner along the shore of New York Harbor and the Kill Van Kull to a terminal near Church Road in Port Richmond, a distance of 9 miles (14 km).[4]: 37 Many residents of Staten Island–landowners, lawyers and some politicians– were opposed to the line's construction. In addition, people connected with the NYCRR and PRR were concerned over Wiman's agreement with Garrett, which threatened their foreign freight trade.[4]: 38, 42

The SIRTR began to seek legislation to acquire various rights-of-way needed to implement Wiman's plan. At that time, his company neither owned nor controlled a railroad; If it gained a charter to build connections, it would have had nothing to connect to. The SIRTR then began surveying for the proposed routes; in April 1881, it acquired 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of critical right-of-way directly from George Law.[6]: 229 When Wiman explained his plan he secured a waterfront option from Law; however, Law refused to renew the option when it expired. To persuade Law to renew it, Wiman offered to name the place "St. George." Law was amused by the gesture and granted Wiman the option.[30]: 4 [31]: 8 In October 1882, Wiman made an application for a wharf to land passengers from the SIRTR's planned new ferry service to Manhattan.[6]: 229 Clarence T. Barrett, Henry P. Judah, and Theodore C. Vermilyen were appointed as commissioners to appraise the value of the land required by the SIRTR to extend the Staten Island Railway to Tompkinsville. Work on the line was delayed until the commissioners reported.[32] The SIRTR filed a map of the proposed route at the office of the Richmond County clerk. The line as planned would cross the lawn of Ms. Post on the North Shore of the island; on February 26, 1883, Mr. Franklin Bartlett and Mr. Clifford Bartlett, on behalf of Ms. Post, notified the court a change of route would be demanded.[33][a]

On April 3, 1883, the SIRTR leased control of the SIRW and its boats from Jacob Vanderbilt for 99 years, assuming full control of all Vanderbilt ferries, including lines to Manhattan and Long Island.[4]: 43 In doing so, it eliminated the conflict between the two railroads, which both crossed at Clifton Junction and did not have coordinated schedules.[4]: 62–63 On the same date, at the annual meeting of the SIRW, Wiman gained control of the railway by being elected to its Board of Directors.[6]: 229 At the meeting, Wiman laid out his proposals for rail lines on Staten Island.[20]: 37 He proposed extending the Staten Island Railway line to Hyatt Street in today's St. George. From there, a line would run through New Brighton and Snug Harbor along the island's north shore before going inland, running parallel to the Kill Van Kull. Additional spur lines would have been built in the interior of the island based on where people settled.[34] Wiman also proposed a bridge across Arthur Kill from Tottenville to Perth Amboy, replacing the ferry that operated there. This would have been part of a direct route between New York City and Philadelphia via Perth Amboy and South Amboy, with a new bridge over the Raritan River. In the days before the meeting, Wiman gained the support of 7,450 out of the 11,800 shareholders to elect him, surprising many of the railroad's directors.[34] By the end of the month, Wiman resigned from the SIRTR to avoid any conflict of interest. On June 27, a meeting of the directors of the SIRW and the SIRTR formally ratified the merger of the two companies under the leadership of Wiman, who was named president.[6]: 229 On June 30, the SIRTR leased the SIRW for a term of 99 years, paying $56,000 annually in rent, to become effective when the line opened between Clifton and Tompkinsville, no later than September 12, 1884.[4]: 65 [1]: 1256 [27]: 569 The line between Vanderbilt's Landing and Tottenville continued to be operated by the SIRW.[1]: 1258

The North Shore Ferry was leased separately and operated by Starin, whose lease was set to expire on May 1, 1884. On July 18, 1884, the SIRTR outbid Starin for its franchise. As part of the purchase, ferry service would have been operated every forty minutes instead of every hour. The fare for the railroad and the ferry would have been ten cents, except between five and seven in the morning and evening, when it would have been seven cents. Starin continued to fight the lease in the courts for several years.[6]: 230 [35] The lease lasted for 99 years, and included the surrounding coastal properties, providing land for the construction of the SIRW's extension between Clifton and Stapleton.[4]: 42

Expansion: 1884–1900[edit]

Line to St. George[edit]

Grading work on the section between Clifton (previously Vanderbilt's Landing) and Tompkinsville began in 1883, starting at Clifton. During early 1884, construction continued with such energy that this section, which had been expected to open on September 1,[32] opened on July 31 that year.[5]: 7 [8]: 690 [36] The first train on the section contained the managers and officers, a few invited guests, and several passengers who had boarded prior to the train's arrival at Tompkinsville. The ride took three and a half minutes.[8]: 690 The opening of the line made the SIRTR's 99-year lease of the SIRW effective; under this agreement, the railroad to Tottenville and its properties became part of the rapid transit system.[8]: 690 [1]: 1256

Wiman wanted to extend the line to St. George so all of the branches under the company's control could meet in one place and connect with the ferries to Manhattan. He was aware of a Cornelius Vanderbilt's failed plan from 1867 to build a new ferry terminal at St. George. William Pendleton, one of the company's officers and stockholders revived the idea. In 1883, Wiman announced plans to built a line connecting Tompkinsville and St. George. He believed that the a ferry terminal would be useless if the railroad was prohibited from connecting to the existing line at St. George. Most of the course of the line, however, had followed the shore along the bluffs, where ground had to be made upon to build the road. State laws could not grant the right to run a railroad through the property of the United States, hindering construction by the grounds of the lighthouse department near Tompkinsville. The United States government refused to sell the land and New York State was unable to gain control of it. Therefore, the company secured an Act of Congress permitting them to tunnel through the government's land on a hill a near the shore, through an easement, with the land atop remaining under Government ownership.[4]: 43–45 The grant for the tunnel was surrounded with restrictions that slowed progress. Construction of the tunnel began in 1885;[5]: 7–8 it was either 985 feet or 585 feet (178 m) long, and was protected by massive masonry walls on the sides and a brick-built arch 2 feet (0.61 m) in thickness overhead. The tunnel was wide enough to fit two trains side by side at a time. The cost of the project was $190,000.[8]: 690–691 Work on the costly tunnel was completed in 1885, and trains from Tottenville were extended to St. George, with ferry services extended to Tompkinsville and Stapleton.[4]: 45

On November 16, 1884, Wiman, James M. Davis, Sir Roderick Cameron, Herman Clark, and Louis de Jonge incorporated the Saint George Improvement Company to handle the land and waterfront, which had been recently purchased from the estate of George Law. The new company was to handle the building of a new ferry terminal at Saint George.[6]: 230 [37]A controlling interest in the SIRTR was obtained by the B&O in November 1885 through purchases of stock. On November 21, 1885, Robert Garrett, President of the B&O,[38] leased the SIRTR to the B&O for 99 years, which gave the B&O access to New York, allowing it to compete with the PRR.[5]: 8 [6]: 230 [20]: 37 Wiman needed the proceeds of the sale to pay for the construction of the North Shore Branch. The funds also helped pay for the construction of a bridge over the Kill Van Kull, the acquisition of 2 miles (3.2 km) of waterfront property, and for terminal facilities at St. George.[39][40] In 1885, Jacob Vanderbilt retired as President of the SIRW. The new lines opened by the B&O were operated by the SIRTR, while the original line from Clifton to Tottenville was called the SIRW,[41][42] which was maintained as a separate corporation.[18][43]: 536 The passenger cars used by the SIRW were leased by the SIRTR.[44]: 841

Opening of the North Shore and South Beach Branches[edit]

The acquisition of the land for the North Shore and South Beach Branches was much more difficult than the extension to St. George. Some owners refused to sell their lands for any suggested price, forcing the railroad to enter court proceedings to have them condemned, taking months or years for the land to be transferred.[4]: 47–48 Construction of the North Shore Branch began on March 17, 1884, after a number of legal proceedings; a party of surveyors started marking out the grades and broke ground for the roadbed.[6]: 230 [32][45] The purchasing and grading of the rights-of-way proceeded as the line between St. George and Clifton was built.[4]: 48–49 The rights of a horse car line to operate in Richmond Terrace were bought to build the line; the right of way followed the island's North Shore and reached a ferry to Elizabeth, New Jersey that had been operating since the mid-1700s.[46] The B&O built about 2 miles (3.2 km) of rock fill out from shore and along the Kill Van Kull to deal with opposition from property owners in the neighborhood of Sailors' Snug Harbor, costing an additional $25,000.[5]: 8 [8]: 691 The company underwent a contest in litigation to acquire property for the line to pass over the cove at Palmer's run.[8]: 691 Some properties in Port Richmond were acquired, displacing several home and business owners. A farm on the northwestern corner of Staten Island at Old Place—which was renamed Arlington by the B&O—was also purchased.[46] Land needed for the South Beach Branch was owned by businessmen that relied on tourism and families that used it for agriculture, and thus, were unwilling to cede their land. The lands needed were given to the railroad in exchange for compensation, and if the lands were were sold again by the railroad, the original owners received preference to repurchase them.[4]: 49–50

The North Shore Branch was completed in 1885 and opened for service on February 23, 1886, with trains terminating at Elm Park. Travel times between Manhattan and Elm Park were reduced from 90 minutes with the old ferry system to 39 minutes.[8]: 691 It was able to be completed this far due to land settlements with land owners on the north shore and George Law. However, it was not completed in full to Arlington and New Jersey because that portion was not yet completed.[4]: 50 On March 8, 1886, the South Beach was completed.[4]: 50

the key piece of Wiman's plan, the St. George Terminal, opened; North Shore trains operated between Elm Park and St. George, and east shore trains operated between St. George and Tottenville.[20]: 37 In early 1886, in anticipation of the opening of the terminal and the consolidation of operations, the former Staten Island Railway stations from Clifton to Tottenville were upgraded from low-level platforms to high-level platforms to match the platforms on the new lines.[18] In mid-1886, the North Shore Branch opened its new terminal at Erastina.[7]: 6 In 1889–1890, a station was built at the South Avenue grade crossing at Arlington as the tracks were extended to the Arthur Kill Bridge.[47] At Arlington, trains were reversed for their trip back to St. George.[18] Even a few years after its opening, most trains terminated at Erastina.[48]

A 1.7-mile (2.7 km)-long branch, then known as the Arrochar Branch, was opened to Arrochar on January 1, 1888, as a double-tracked line.[49][50]: 257–258 The branch split off at Clifton Junction; it had two stops—Fort Wadsworth and Arrochar. In its first year, the branch carried heavy traffic, especially during the summer months.[50]: 257–258 As evidenced by a map from 1884, the South Beach Branch was originally intended to run to Prominard Street in Oakwood Beach.[24][51][52] The extension, however, was not built because the SIRTR could not gain the Vanderbilt family's approval to cross their New Dorp Beach farm.[18] Instead, the line was only built as far as South Beach. During fiscal year 1893, the SIRTR purchased land to extend the line 1.75 miles (2.82 km) to South Beach and the 2.3-mile (3.7 km) South Beach Branch was completed in 1894.[1]: 1259

The B&O takes control[edit]

On October 28, 1885, the agreement between the SIRTR and the B&O became a contract. As part of the deal, the SIRTR agreed to build and finish its lines and the bridge over the Kill Van Kull within a year of the agreement, unless that it is delayed from hostile proceedings, upon which it was to be completed as quickly as possible. The B&O agreed to build the line in New Jersey, and to bring capital into the SIRT and buying certain land parcels and stock in the company. The SIRT granted the B&O the right to use the line to transport its freight and passengers, and mail across the line for 99 years. For the agreement to take effect, the land between the Arthur Kill and Port Richmond still had to be purchased, and the B&O had to obtain a route to the New Jersey shore where the bridge was to be built.[4]: 50–54 To obtain the land, Wiman used the New York case titled Gould v. the Hudson River Railroad to argue that the SIRTR had the authority from the state Legislature to condemn property to complete the line–those of the the Coast Wrecking Company and land owned by New York State in Mariner's Harbor and the Marine Society of the City of New York. In court hearings, the court repeatedly asked why the SIRT needed the extra lands if it was a local railroad, and what the role the B&O, and its subsidiary, the Baltimore and New York Railway (B&NY), in the project. In the end, the lands were awarded on the basis of the Gould case. The B&O had trouble with its route because the New Jersey State Legislature passed a law prohibiting a railroad bridge from being built between the two states in the areas of Cranford Junction, Elizabethport, Bayway and Staten Island, and because the Jersey Central refused to lease its line. In October 1888, the B&NY was created, through which, the Jersey Central allowed the B&O to run freight and passenger trains. The New Jersey Legislature rescinded their law after reviewing actions of the U.S. Congress on the issue, and construction subsequently began.[4]: 54–61

A controlling interest in the SIRTR was obtained by the B&O in November 1885 through purchases of stock. On November 21, 1885, Garrett[53] leased the SIRTR to the B&O for 99 years, which gave the B&O access to New York, allowing it to compete with the PRR.[5]: 8 [6]: 230 [20]: 37 The funding provided Wiman the funding needed for the completion of the North Shore Branch.[4]: 54 The funds also helped pay for the construction of a bridge over the Kill Van Kull, the acquisition of 2 miles (3.2 km) of waterfront property, and for terminal facilities at St. George.[54][55] In 1885, Jacob Vanderbilt retired as President of the SIRW. The new lines opened by the B&O were operated by the SIRTR, while the original line from Clifton to Tottenville was called the SIRW,[41][42] which was maintained as a separate corporation.[18][43]: 536 The passenger cars used by the SIRW were leased by the SIRTR.[44]: 841

Extension to New Jersey[edit]

The B&O made various proposals for a railroad between Staten Island and New Jersey. The accepted plan consisted of a 5.25 miles (8.45 km) section from the Arthur Kill to meet the Jersey Central at Cranford, through Roselle Park and Linden in Union County. In October 1888, the B&O created the subsidiary Baltimore & New York Railway (B&NY) to build the line, which was to be operated by the SIRTR. Construction started in 1889 and the line was finished later that year.[5]: 8 [46] After three years of effort by Wiman, Congress passed a law on June 16, 1886, authorizing the construction of a 500-foot (150 m) swing bridge over the Arthur Kill.[20][56] The start of construction was delayed for nine months because it awaited approval of the Secretary of War,[5]: 8 and another six months due to an injunction from the State of New Jersey. Construction had to continue through the brutal winter of 1888 because Congress had set a completion deadline of June 16, 1888; two years after signing the bill.[20]: 37–38 [56] The bridge was completed three days early on June 13, 1888.[56][57] Upon its opening, the SIRTR's right-of-way was extended into New Jersey as part of the 1885 agreement, making it an interstate railroad.[4]: 60–61

When it opened, the Arthur Kill Bridge was the largest drawbridge ever constructed; it cost $450,000 and was constructed without fatalities. The bridge consisted of five pieces of masonry; the center one being midstream with the draw resting on it. The bridge's drawspan was 500 feet (150 m), the fixed spans were 150 feet (46 m), and there were clear waterways of 208 feet (63 m) on either side of the draw, making the bridge 800 feet (240 m) wide. The bridge was 30 feet (9.1 m) above the low water mark. Construction of the draw needed 656 tons of iron, and 85 tons were needed for each of the approaches. Trains were planned to start running on the bridge by September 1,[56] but because the approaches were not finished, this was delayed until January 1, 1890,[5]: 8 when the first train from St. George to Cranford Junction crossed the bridge.[58] Because the land for the approaches was low and swampy, 2 miles (3.2 km) of elevated structure was built; 6,000 feet (1,800 m) on Staten Island and 4,000 feet (1,200 m) in New Jersey.[58] The North Shore Branch was opened to freight traffic on March 1, 1890.[1]: 1259–1260 On July 1, 1890, all of the B&O's freight traffic started using the line.[59] The B&O paid the SIRTR 10 cents-per-ton trackage to use the line from Arthur Kill to St. George.[43]: 537 Once the Arthur Kill Bridge was completed, pressure was brought upon the United States War Department by the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the PRR to have the newly-built bridge torn down and replaced with a bridge with a different design, claiming it was an obstruction for the navigation of coal barges past Holland Hook on the Arthur Kill. Their efforts were not successful.[20]: 37 [46] Freight service increased dramatically with the opening of the B&O connection. William Pendleton completely unified the ferry systems on the island's east and north shores under the SIRTRC by 1891.The B&O increased its volume of foreign trade by a great mount, since it was much cheaper and easier for ships to deposit cargo in Staten Island instead of traveling north to New Jersey or Manhattan or Brooklyn.[4]: 67–69

Wiman, leveraging railroad access, embarked on projects to invite tourism to the island, including the construction of the first western rodeo show ranches ever on the east coast of the U.S. and built a boardwalk and hotel at South Beach to rival Coney Island. Many tourists from New Jersey, Long Island and Manhattan, came, and South Beach was a boom for the economy of Staten Island in the summers of the early 1890s.[4]: 69–70

In September 1890, Wiman secured the rights for a tunnel between Brooklyn and Staten Island; these tunnel rights were acquired by the New Jersey and Staten Island Junction Railroad Company. In May 1900, the PRR and other railroads secured an informal agreement to use the North Shore Branch from the Arthur Kill Bridge and the tunnel rights for a tunnel to 39th Street in Brooklyn. This was intended to allow freight trains to travel directly between Boston and Washington.[60]

Perth Amboy Sub-Division improvements[edit]

To improve service, under B&O control, a large portion of the line was double-tracked. A second track was built between New Dorp and a point near Clifton in 1887 and 1888.[50]: 257 [61] Two new stations, Garretson and New Dorp, were opened the following year.[1]: 1259 In 1893, while doing well financially, the SIRTRC increased its capital from $900,000 to $1,050,000. 51% of these shares went to the B&O as part of the 1885 agreement. The increase in capital paid for maintenance and improvements, including the construction of rights-of-way to the ports of Howland Hook and Port Ivory on the north shore, Travis on the west shore, Mt. Loretto on the south shore, and many coal sidings and freight yards connected to private business.[4]: 69–71 In addition, funds were used for double-tracking and a new station at Tottenville.[61] In 1895, land in St. George and Stapleton was acquired for yard space and station use.[62][63]: 482 Between June 1895 and December 1895, the line was double tracked to Annadale. Between 1896 and 1899, the portion of the 12.64-mile (20.34 km) line that was double tracked was increased from 5.8 miles (9.3 km) to 10.04 miles (16.16 km).[43]: 536 [63]: 485

In 1896, the terminal at Tottenville was moved 600 feet (180 m) to provide closer connections to the Perth Amboy Ferry and to provide new ferry slips.[64] The terminal had been located on the east side of Main Street but as part of the work it was moved to Bentley Street. The change had a negative effect on local businesses, changing the character of Main Street and marking a decline of its commercial viability.[65] To build the new terminal, property had to be acquired.[1]: 1255 [66]: 847 In 1910, the SIRW stopped using the land for the old ferry docks at Main Street.[44]: 834

Reorganization[edit]

The B&O was bankrupt by February 1896; in its attempt to reach the New York market, its western lines fell into disrepair. J.P. Morgan replaced the railroad's top management and refinanced it.[46] The new terminal at St. George was completed in 1896 after work was contracted for the project in fiscal year 1893.[67]: 569 The building was designed by the architects Carrere and Hastings, and was built with ironwork framing. At the time, it was the largest terminal in the United States to have ferry, rail, vehicular, pedestrian and trolley services. Trolley companies on Staten Island insisted on access to the new terminal, but were rebuffed by the B&O. The issue went to court, and the B&O ended up splitting the cost for the trolley terminal and the long viaduct with the trolley operators.[68] Prior to October 1897 passengers placed their tickets into ticket choppers at stations to pay their fare. Afterwards, conductors collected tickets.[69]

In 1895, electric trolley service was inaugurated on Staten Island; it attracted passengers from the SIRTR, ending the railroad's monopoly. As a result, the railroad went into bankruptcy.[7] The railroad's only competition had been slow horse-cars. The Staten Island Midland Railway Company, the Staten Island Electrical Railroad Company (SIERC), and the Staten Island Belt Line Company, purchased by the SIERC, became formidable competitors to the SIRTRC due to their lower fares, and because they extended to the inner parts of the island that the railroad did not serve. The trolleys ran on schedule more frequently and were cleaner to take. Ridership on the SIRTR decreased as its monopoly broke. Wiman tried to prevent the loss of ridership by establishing his own trolley service fighting the trolley companies. Services were completely halted, with the exception of the B&O freight service by 1898.[4]: 71–74

On April 20, 1899, the railroad company and all of the real and personal property held in the company was sold at auction, and to prevent it from falling into the hands of the PRR and the NYCRR, for $2,000,000 to representatives of the B&O.[4]: 75–77 [14]: 464 [70] The railroad already owned the line from Elizabethport, New Jersey to South Beach, including the Arthur Kill Bridge. At the time, it was rumored the B&O trains would be rerouted from Communipow station to Saint George. There was no change in the SIRTRC's management after the purchase.[70] On July 1, 1899, the SIRTR defaulted on its payment of interest on its second mortgage bonds, and its lease of the Staten Island Railway ended on July 14 when it was put into receivership.[71]: 780 On July 31, 1899, the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway Company—also shortened to Staten Island Rapid Transit, or SIRT–was incorporated for the purpose of operating the SIRTR, with the new certificate of incorporation filed on July 28, and the transaction taking place on August 1, 1899.[72]: 511 The new company's maximum capital was $500,000. The terms of the certificate of incorporation stated that the SIRT was an official B&O company.[4]: 78–79 The section of the SIRT's line between St. George and Clifton Junction was jointly operated with the SIRW.[1]: 1246, 1257, 1250, 1262 Initially, the new organization did well, and the B&O operated its freight routes at a great profit. Due to declining ridership, and lack of profit, passenger service over the Arthur Kill was discontinued.[4]: 79–80

Modernization: 1900–1949[edit]

Pennsylvania Railroad control: 1900–1913[edit]

Pennsylvania acquisition[edit]

Improvements were made to the SIRT after the PRR under the leadership of president Alexander Cassatt took control of the B&O. Cassatt was named president of the PRR in 1899, and he allied with the NYCRR for a "community of interest" plan. Cassatt wanted to end the rebate practice being undertaken by Standard Oil and Carnegie Steel—both larger shippers—that kept the freight rates extremely low. To achieve this, the two railroads bought stock in smaller, weaker trunk line railroads. The New York Central bought stock in the Reading Company, while the PRR bought stock in the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, the Norfolk Southern Railway, and in the B&O—including the SIRT and the ferries on Staten Island. The plan worked; the average freight rate for the two companies rose. Cassatt first purchased B&O stock in 1899, most of it being under PRR control by 1901. After the PRR took more direct control of the B&O, including the SIRT; in May 1901, improvements were made to the rail line. PRR control of the line decreased as a new PRR president had different priorities, and in 1906, the PRR sold half of its B&O stock to the Union Pacific Railroad. The remainder of the PRR's stock in the B&O was sold to the Union Pacific in 1913.[73]: 194–195, 199–200

Improvements[edit]

Under PRR control, the B&O was profitable again and became a stronger railroad.[46] The PRR allowed the B&O's newly developed properties to remain intact. On October 13, 1903, the SIRT started a trial passenger service from Plainfield, New Jersey to St. George, running via the Jersey Central past Cranford Junction. The SIRT operated four trains every day, except for Sunday, with direct connections with the B&O's Royal Blue service between New York City and Washington, D.C. at Plainfield. These trains consisted of a locomotive and two passenger coaches. While this service was in operation the B&O sold tickets for its main line trains at the railroad's ferry terminals in Brooklyn, at South Ferry, and at St. George.[24] The service was discontinued in 1903 because it was unprofitable.[74][75] The PRR bought four large double-decker steamers to halve the travel time on the Staten Island Ferry.[76]: 29

In 1905, the ferryboat Maush Chash of the Jersey Central crashed in New York Harbor with the SIRT ferryboat Northfield, killing six passengers. The B&O was blamed for the accident, since both ferryboats were owned by its subsidiaries. The City of New York, which formed in 1898, ordered the B&O to relinquish total control of the ferries it acquired in 1899, and threatened to legally oust it from Staten Island. The B&O was ejected from the Whitehall Street terminal on October 25, 1905, handing over ownership of the ferry and terminals, and selling the Perth Amboy ferry to a private company. Under city ownership, St. George Terminal was rebuilt for $2,318,720.[76]: 29 After the accident, the SIRT started losing ridership, and freight operations began decreasing.[4]: 80–82

The PRR increased the number of daily trips to 28, and in 1902, it began contemplating the electrification of the rail line. The PRR's investment in the southern portion of the Perth Amboy sub-division was credited for the increased development of the South Shore of Staten Island. As such, in about 1902, a new station was constructed at Whitlock to serve a new community being built by the Whitlock Realty Company on the South Shore. The development company incentivized prospective buyers to bid on newly-built houses by promising a year's free commuting between Manhattan and Whitlock for the first 25 houses.[77] In December 1912, the SIRT petitioned the Public Service Commission (PSC) to allow the railway to abandon the station and replace it with a station named Bay Terrace 1,594 feet (486 m) to the south. The change was made, anticipating a shift in the center of population in the community.[22][78] After 1900, several new houses were built in the community of Annadale and several parts of the Little Farms development. In 1910, as part of the development, the building company built a new railroad station.[79] As a result, on March 22, 1910, the SIRT petitioned the PSC to allow it to discontinue its service at Annadale station and replace it with a new station of the same name 450 feet (140 m) to the west.[80][20]: 189

Between 1905 and 1911, B&O President Daniel Willard changed the name of the SIRT to the Staten Island Railway Company, and tried to improve service. By 1912, ridership decreased to 2,468,649 passengers per year, one million less than average, and it had lost $1 million in revenue.[4]: 82

Increase in traffic[edit]

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 67 |

| 1944 | 81 |

| 1960 | 37 |

| 1967 | 38 |

In 1890 and 1906, respectively, the car float terminal and freight yard at Saint George and Arlington Yard were opened.[24] The two main freight yards on Staten Island, Arlington and Saint George, were at capacity, and in 1912, to ease the congestion, the B&O began running freight via the Jersey Central into Jersey City. The B&O profited from the heavy coal trade that operated via the lines on Staten Island.[46] In 1920, 4,000,000 tons of freight had been handled on the railway. In addition, passenger traffic on the line increased. Between 1903 and 1920, daily trips on the North Shore Branch increased from 50 to 65; from 50 to 60 on the South Beach Branch; and from 22 to 34 on the Tottenville Branch.[81] In 1920, 65 trains ran daily on the North Shore Branch; 60 trains ran daily on the South Beach Branch; and 34 trains ran daily on the Tottenville Branch. Most of the railway's passengers used the North Shore and South Beach branches. In 1920, 8,000,000 passengers used the North Shore and South Beach branches while 5,000,000 passengers used the main line.[82] Up to 1921, 3,369,400 trains had been operated on the SIRT with no fatalities.[83]

Electrification: 1923–1925[edit]

With the goal of increasing passenger revenues, the B&O planned on connecting with the rest of New York City through a connection in Brooklyn, and began negotiating with the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT), which proposed the inclusion of the idea under the Dual Contracts in 1913. The proposal would have connected the BRT's Fourth Avenue Line with the Perth Amboy Sub-Division by a tunnel running underneath the Narrows. The project was delayed between 1914 and 1919 due to World War I, and the Malbone Street Wreck of November 1918. During World War I, the Clifton rail docks and the terminal at St. George were used to transport war materials and soldiers to Europe. President Woodrow Wilson ordered a federal takeover of all railroad lines in the United States during the war, during which the B&O made a profit, helping prop the SIR back up. The Malbone Street Wreck bankrupted the BRT, which reorganized as the BMT, or Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit. With the prospect of the connection, ridership on the SIR increased as real estate agents began to speculate and promote sales in Staten Island. By 1921, ridership reached 13 million per year, and that year, the City Transit Commission recommended the construction of the tunnel, which was adopted in 1923 by the BMT and the SIR. Six tunnel routes were proposed, and one was adopted on December 16, 1924. The route would have branched off the BMT Fourth Avenue Line subway south of the 59th Street station, running under Bay Ridge Avenue and the Narrows to St. George, from where it would be built under the North Shore and streets in the center of the island, such as Forest Avenue. One shaft of the tunnel was sunk and sealed in 1924, and the project was was halted due to Mayor John Francis Hylan's insistence that no new funds go to the BMT.[4]: 83–89 Though the BMT and SIR began to construct it using their funds, it was not sufficient. The B&O planned to use this tunnel to connect its freight from New Jersey to freight terminals in Brooklyn and Queens, including to a planned port at Jamaica Bay. The city started construction on the Narrows tunnel in 1924. Due to political pressure and the project's increasing cost, the freight tunnel portion of the plan was eliminated in 1925, and the entire project was halted in 1926. Only the shafts at either end were constructed.[20]: 133

On June 2, 1923, the Kaufman Act was signed by Governor Al Smith, mandating that all railroads in New York City–including the SIRT—be electrified by January 1, 1926.[84][85] As a result, the B&O drew up electrification plans, which were submitted to the PSC. The plans were approved by the PSC on May 1, 1924, and construction began on August 1, 1924. The SIRT was to be electrified using 600 volt D.C. third-rail power distribution so it would be compatible with the BMT.[86] The grades on the three lines were changed in the same manner of the BMT lines.[4]: 90 The SIRT ordered ninety electric motors and ten trailers (later converted to motors) from the Standard Steel Car Company to replace the old steam equipment.[20]: 133 These cars, the ME-1s, were designed to be similar to the Standards in use by the BMT.[86] The cars were painted black with grey roofing and gold lettering saying "Baltimore and Ohio Railroad." These cars had to conform to the requirements of the New York City transportation and Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) codes, because it was a rapid transit line and an interstate railroad. The railroad was regulated as a First Class Railroad, meaning that it grossed over $3 million in a year.[4]: 91–92

The first electric train was operated on the South Beach Branch between South Beach and Fort Wadsworth on May 20, 1925, and regular electric operation began on the branch on June (2)5, 1925.[87]: 7805 [4]: 92 As part of the electrification project, the South Beach Branch was extended one stop to Wentworth Avenue from the previous terminus at South Beach.[22][88] Wentworth Avenue had a short, wooden, half-car platform, and a shelter was built there. That location had previously been used as a servicing and turning point for the line's steam-powered locomotives.[18] Electric service began on the Perth Amboy sub-division on July 1, 1925, to much fanfare.[87]: 7805 [89] The North Shore Branch's electrification was completed on December 25, 1925, and resulted in a time savings of ten minutes from Arlington to St. George.[7][90] From 1925 to 1930 the B&O fenced off all parts of the rights-of-way. Additional tracks were added for freight service so as to not interrupt passenger service.[4]: 96

Because of the high cost of electrification, however, St. George and Arlington Yards, along with the Mount Loretto Spur, and the Travis Branch were not electrified.[5]: 8 Thirteen steam engines were retired and four new, wholly automatic substations opened at South Beach, Old Town Road, Eltingville, and Tottenville. Five electrical power substations were built along the Perth Amboy Sub-Division, and three were built along the North Shore Division. The SIRT's old semaphore signals were replaced by new electric color position light signals to facilitate service on 20 miles (32 km) of double tracking on the lines.[4]: 90–91, 93 This was the first permanent use of the type of signal on the B&O–it later became the railroad's standard.[20]: 133 A modern signaling system was put into place in the Saint George Yards, allowing one dispatcher to do all the work. The Clifton Junction Shops were updated to maintain electric equipment rather than steam equipment, and a large portion of the yard was electrified. Grade crossing elimination began between Prince's Bay and Pleasant Plains.[85] While electrification was being installed, the system's roadbed was rebuilt with 100-pound rail.[91] Upon electrification in 1925, the name of the railroad reverted to the Staten Island Rapid Transit Railway Company.[4]: 94

The promise of a faster, more reliable electrified service spurred developers and private individuals to purchase land alongside the SIRT lines, with the intention of providing housing to attract residents to Staten Island.[92] On July 2, 1925, for the first time since its opening, the railroad stopped reserving its trains' first car for smokers. A petition was sent to the railroad to reverse this decision.[93]

Tottenville station was destroyed by a fire on September 3, 1929. The fire was attributed to a short-circuited third rail. The two 550 foot (170 m)-long platforms were destroyed, as were six new train cars being stored near the station. The damage was estimated to cost $200,000. Passengers using the Perth Amboy Ferry were forced to use the nearby Atlantic station instead.[94] With the loss of cars, the schedule had to be modified so that specific runs could be maintained.[4]: 96

Expansion[edit]

In the 1920s, a branch was built to haul materials to construct the Outerbridge Crossing. The branch ran along the West Shore from the Richmond Valley station, and originally ended at Allentown Lane in Charleston, past the end of Drumgoole Boulevard. The bridge connected Perth Amboy and Staten Island by road, and opened in 1931, making it possible to get to Perth Amboy without having to take the train or ferry.[4]: 97–98

The branch was cut back south of the bridge after the bridge was completed. The Gulf Oil Corporation opened a dock and tank farm along the Arthur Kill in 1928; to serve it, the Travis Branch was built south from Arlington Yard into the marshes of the island's western shore to Gulfport.[5]: 41 [18] At this time, the B&O proposed to join the two branches along the West Shore. The West Shore Line, once completed, would have allowed trains to run between Arlington on the North Shore sub-division and Tottenville on the Perth Amboy sub-division. In addition, freight from the Perth Amboy sub-division would no longer be delayed by the congestion of Saint George Yard and the frequent passenger service of the SIRT. This proposal was canceled because of the Great Depression.[18]

In the 1930s, there was a proposal to build a loop joining the Perth Amboy sub-division at Grasmere with the North Shore Branch at Port Richmond. There also was a proposal to join the North Shore Branch to Tottenville without using the existing West Shore tracks.[18] Staten Island Borough President Joseph A. Palma, in 1936, proposed to extend Staten Island Rapid Transit to Manhattan (via New Jersey) across the Bayonne Bridge, which had been built to accommodate two train tracks.[95][96] The Port of New York Authority endorsed the second plan in 1937, with a terminal at 51st Street in Manhattan near Rockefeller Center to serve the trains of Erie, West Shore, Lackawanna, Jersey Central, and trains from Staten Island.[97] This original proposal would be brought back in 1950, by Edward Corsi, a Republican candidate for Mayor of New York City.[98]

On February 4, 1932, the headway on trains was decreased to 15 minutes from 20 minutes between 9:29 p.m. and 10:29 p.m.; and was decreased to 30 minutes from 40 minutes between 10:29 p.m. and 1:29 a.m. on the Perth Amboy Sub-Division.[99]

On June 14, 1948, a bill to permit the SIRT to widen its railroad tunnel at the Saint George Ferry Terminal was signed into law.[100] The tunnel, which was constructed under Federally-owned land, was widened 19 feet (5.8 m) for a distance of 456 feet (139 m).[101] The tunnel allowed for the laying of a third track, and permitted the operation of more trains from Saint George to Tottenville and South Beach. The extra track also facilitated better handling of trains at the ferry terminal at Saint George.[102]

Grade crossing elimination: 1912–1950[edit]

On December 26, 1912, the City of New York granted the SIRT the right to construct a second track between Huguenot and Pleasant Plains, with completion expected in three years. The grant was for 25 years but this project was not completed until 1934.[1]: 1256 [103] During fiscal year 1915, a second track was completed between Annadale and Pleasant Plains, and grade crossings elimination projects were undertaken at Amboy Road, Huguenot Park, and Pleasant Plains.[44]: 834

In August 1917, the PSC adopted an order directing the SIRT and other railways to keep the gates at 33 grade crossings closed between midnight and 5 a.m. for vehicle safety.[104] On June 25, 1926, the Transit Commission ordered the elimination of four grade crossings on Staten Island—at Bay Street in Clifton, and at Hope Avenue, Belair Road, and Tompkins Avenue in Fort Wadsworth. The project would cost $1,000,000, with half of the cost going to the railroad and a quarter each to the city and state. At the time, the grade crossing at Bay Street was thought of as the most dangerous grade crossing on Staten Island.[105] The SIRT sued the Transit Commission, arguing that it did not have the power to order the construction of such projects. The Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Transit Commission on July 23, 1926. The case was carried to the Supreme Court, which decided to hear the case "for a lack of jurisdiction."[6]: 238

Between 1930 and 1939 the railroad engaged on a grade-crossing elimination program on all three sub-divisions, with most of the funds granted by the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Work continued on fencing the right-of-way.[4]: 96–97 On the Perth Amboy sub-division, a large grade-elimination project took place on the southern portion of the line. The project was completed in 1934; new brick stations were built and the single-track portion of the line that ran through Skunk's Misery was double-tracked; the latter requiring a lot of rock fill.[18]

The Grasmere–Dongan Hills grade crossing elimination project was completed in 1934. The project eliminated 11 crossings and cost $1,576,000. The crossings were removed by putting the line in an open cut through Grasmere and elevating it through Dongan Hills.[99]: 27–28 As part of the project, a new street, North Railroad Avenue was constructed, paralleling the line's north side from Clove Road to Parkinson Avenue.[106]: 46

The East Shore sub-division was elevated in 1936–1937 to remove several grade crossings.[88][107] A huge undertaking was required to remove grade crossings on the North Shore sub-division. The Port Richmond-Tower Hill viaduct was built to remove eight grade crossings; it was longer than a mile and became the largest grade crossing elimination project in the United States. The viaduct opened on February 25, 1937, marking the final part of a $6,000,000 grade crossing elimination project on Staten Island, which eliminated 34 grade crossings on the north and south shores. A two-car special train, which carried Federal, state, and borough officials, made a run over the viaduct and the seven-mile project. Stations closed for the viaduct project at Tower Hill and Port Richmond were reopened on this date.[108]

Between 1938 and 1940, a grade crossing elimination project was undertaken over three miles between Great Kills and Huguenot, eliminating seven grade crossings and costing $2,136,000, which was partially paid for by the city, state, and Progress Work Administration funds.[109][110]: 50 The line was depressed into an open cut between Great Kills and Huguenot, with the exception of a section through Eltingville where it was elevated.[111] Four stations—Great Kills, Eltingville, Annadale and Huguenot—were completely replaced with new stations along the rebuilt right-of-way. The project started on July 13, 1938, and was completed in October 1940.[112][113]: 45 The stations themselves were completed in 1939, and therefore have the date 1939 inscribed either on road overpasses or on railroad bridges.[114]

In that same year, grade crossing eliminations were completed in Richmond Valley and Tottenville. The Richmond Valley project eliminated the crossing at Richmond Valley Road and cost $300,000 while the Tottenville project eliminated seven crossings—including one at Main Street—and cost $997,000.[115][116][117] The only remaining grade crossings to be removed were at Grant City, New Dorp, Oakwood Heights, and Bay Terrace. These projects were delayed due to material shortages during World War II.[118] In 1949, a project to eliminate 13 grade crossings on the Perth Amboy sub-division, at Grant City, New Dorp, Oakwood Heights and Bay Terrace, was set to begin, with a projected cost of $7,400,000.[119] On August 30, 1950, the PSC announced a $6,500,000 plan to eliminate grade crossings of the SIRT. The plan was only approved with the assurance from the city that if passenger service was discontinued, the city would guarantee residents of the area would have some form of public transportation. The plan also included the construction of a bridge over the never-built Willowbrook Expressway.[120]

World War II[edit]

Freight and World War II traffic helped pay off some of the debt the SIRT had accumulated, briefly making it profitable, and making it a solvent company for the first time. Freight traffic on the North Shore Division increased significantly.[4]: 98–99 B&O freight trains operated to Staten Island and Jersey City. Around this time, B&O crews began running through without changing at different junctions. Regular B&O crews and Staten Island crews were separated, meaning the crews had to change before they could enter Staten Island. All traffic to and from Cranford Junction in New Jersey was handled by the SIRT crews. During the war, all east coast military hospital trains were handled by the SIRT—the trains came onto Staten Island through Cranford Junction, with some trains stopping at Arlington to transfer wounded soldiers to Halloran Hospital. Freight tonnage doubled on the SIRT between 1942 and 1944 to a record 3.2 million tons. The Baltimore & New York Railway line become extremely busy, handling 742,000 troops, 100,000 prisoners-of-war, and war material operating over this stretch to reach their destinations.[20]: 161 With gasoline rationing for buses and cars during the war, passenger service increased, with many people going to South Beach during the summer.[4]: 98

Two B&O subsidiaries, the B&NY and the SIRT, were merged on December 31, 1944.[121]: 605 [122] Since the Baltimore & New York Railway opened in 1890, the SIRT operated this line with locomotives belonging to itself and to its parent company, the B&O. Around the time of World War II, the B&O operated special trains for important officials. One special was operated for former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Sir Winston Churchill. The train secretly took him to a meeting and New Jersey and back to Stapleton, from where he boarded a ship to Europe. The SIRT made special arrangements for the trip, including a shined-up locomotive sporting polished rods, white tires, and an engine crew clad in white uniforms.[46][4]: 99

On June 25, 1946, a fire wrecked the terminal at Saint George, killing three people, including a ticket agent, and causing damage worth $22,000,000.[20]: 55 The fire destroyed the 90 percent wooden ferry terminal and the four slips used for Manhattan service, the terminal for Staten Island Rapid Transit trains, and a small building and slip owned by the city and used by the Army and Navy to transport personnel from Staten Island to the United States Naval Depot at Bayonne, New Jersey.[123] Twenty rail cars were also destroyed in the fire.[124] Since the power circuits were melted, the electric MUs were trapped in the station. Diesel cars were sent to rescue them, but wouldn't couple with the MUs due to their different coupling systems. Some cars were saved through the use of rigging tow chains, but precious minutes were lost. (8?)5 cars were totally destroyed in the fire, while 16 suffered heavy damage. A few cars were sent to Clifton shops, with the others kept at St. George with their windows boarded up.[125] Ridership dropped, like in 1872, 1905 and 1927, following safety concerns.[4]: 99–100

Two days after the fire, the city voted $3,000,000 to start work on a new $12,000,000 terminal that would be opened in 1948.[126] Until a temporary terminal could be built at Saint George, Tompkinsville was used as the main terminal on the Perth Amboy Division. Even though the station was very narrow and its facilities were inadequate, service continued without an issue and without any injuries. The station handled the equivalent of 128 passenger loads per day.[91] North Shore Division tranis terminated at Pier 6. On June 8, 1951, a modern replacement terminal for Saint George opened, although portions of the terminal were phased into service at earlier dates.[127] The new terminal consisted of 12 platforms and a yard. The SIRT only had 86 cars, with 8 being repaired.[4]: 100

Service scaledowns and the end of B&O operation: 1947–1971[edit]

Transfer of ferry service: 1947–1948[edit]

On October 28, 1947, the SIRT filed with the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to get permission to discontinue ferry service between Tottenville and Perth Amboy Ferry Slip in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. The SIRT said the abandonment should be permitted because of "the substantial deficits being incurred in operation of the service, which covers a distance of 3,600 feet".[128] On September 22, 1948, the ICC allowed the SIRT to abandon the ferry, which it had been operating for 88 years. On October 16, the ferry operation was transferred to Sunrise Ferries of Elizabeth, New Jersey, which had agreed to lease the railway's ferry facilities at Tottenville and to lease Perth Amboy wharf and dock properties there.[129][130] The schedules and the five-cent fare for the ferry were maintained.[131] In 1963, Perth Amboy ferry service was discontinued.[132]

Service cuts and the discontinuation of service: 1948–1953[edit]

On October 28, 1947, Mayor John Delaney of Perth Amboy created a plan to fight the SIRT's proposal to abandon service between St. George and Tottenville. The Mayor criticized the railroad for failing to notify the city of its intentions.[133] This effort to discontinue service failed, but on February 23, 1947, the New York City Board of Transportation (BOT) took over all of the bus lines on Staten Island, which belonged to Stone and Webster Corporation, and later Isle Transportation Company.[5]: 8 On June 1, 1948, the zone fare system was abolished to match the fare of the other city-owned bus lines, dropping the bus fare on Staten Island dropped from five cents per zone (twenty cents Tottenville to the ferry) to seven cents for the whole island. Transfer tickets were introduced allowing passengers to use a bus, the ferry and the subway at no extra charge. Even though the buses had run poorly, the cheaper bus fare resulted in an exodus of passengers from the SIRT. Most bus routes ran parallel to the SIRT's lines.[4]: 101–103 In 1947, the SIRT had carried 12.3 million passengers but after the decrease in bus fares the number decreased to 8.7 million in 1948 and to 4.4 million in 1949.[134] Three months after the change, passenger traffic dropped 32 percent on the Tottenville Division and 40 percent on the other two divisions. The buses saw a 25 percent increase in ridership.[135] By 1950, the SIRT lost 60% of its ridership since 1947.[4]: 103

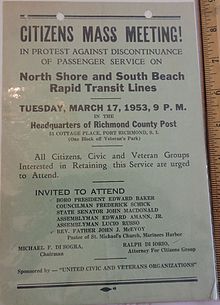

Due to the loss of ridership, on August 28, 1948, the SIRT announced it would reduce service on all three branches on September 5. Service would be reduced from 15-minute intervals in non-rush hours to 30 minutes during that time, and from 5 to 10 minutes in rush hours to 10 to 15 minutes during rush hours.[136] The day afterwards, Richmond Borough President Cornelius A. Hall and Staten Island civic organizations announced they would oppose the proposed cuts.[137] The PSC elected not to prevent the cut in service on September 2, 1948, and the cut went into effect three days later. 237 of the previous 492 weekday trains were cut and the schedule of expresses was reduced during rush hours. In addition, all night trains after 1:29 a.m. were eliminated. The reduction of trips resulted in the firing of 30 percent of the company's personnel.[138][139]