User:Johnbod/Animals

Representations of animals in art go back to the earliest times, and are found in most cultures. They have served a variety of purposes.

Tomb figures[edit]

A number of cultures have made models of animals to be placed in tombs, in the belief that this will lead to the animals being available to the deceased in the afterlife. The pottery Tang dynasty tomb figures from China, at their peak around 700-750, include large numbers of horses, mostly saddled but awaiting their rider, and camels with riders, perhaps representing wealth. These were placed in large numbers in the huge tombs of the Tang dynasty elite.[1] They develop a much longer tradition that more often features farm animals in more humble tombs.

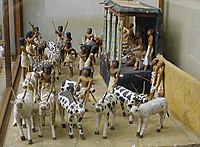

Ancient Egyptian art produced similar small model farm animals to provide for the dead.[2] Japanese haniwa figures are mostly human, but include animals, especially horses.

-

Egyptian wooden tomb models, Dynasty XI; a high administrator counts his cattle

-

Unglazed camel and Sogdian rider, Tang

-

Glazed bull, Tang

Horses[edit]

Horses first appeared in Palaeolithic cave paintings when they were popular prey animals, not yet domesticated.[3] After horses became domesticated, they became crucial in warfare in Eurasia, first for pulling chariots, and later for cavalry.[4] For some nomadic or very mobile cultures, in particular Eurasian steppe nomads such as the Scythians, and later in the American West, the entire way of life depended on horse transport.[5] They also retained their status as a prestige possession and method of transport until modern times, and horseriding remains a prestigous sporting and leisure pursuit.

The equestrian statue, very difficult and expensive to make at full-size, developed in the classical world, where they were very rare before the Roman Empire. The fragmentary stone Rampin Rider, of about 550 BC, is the best very early survival. The Chinese Terracotta Army has many riders standing beside their mounts, but no mounted riders. The famous Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, of c. 175 AD, is much the best survival of the imperial period, the late Roman Regisole having been destroyed by the Jacobins of Pavia in 1796. These directly inspired later statues from the Renaissance onwards, among the earliest being that in painted wood of Paolo Savelli at Basilica dei Frari in Venice, followed by life-size bronzes: Donatello's Equestrian statue of Gattamelata of 1453, followed by that of Bartolomeo Colleoni by Andrea del Verrocchio (1480–88).[6] All these subjects were condottiere or leaders of mercenaries, but by the Baroque period every male monarch in Europe wanted to be portrayed on a horse. Life-size statues with female riders are much rarer; Joan of Arc may be the first woman to be so portrayed, in the 19th century. The over-ambitious Leonardo's horse, intended to be over twice life-size, never got further than a clay model, after his patron diverted the bronze he had allocated to make cannon instead.

The painted equivalent of the life-size equestrian statue begins with memorial frescos such as Guidoriccio da Fogliano at the siege of Montemassi, probably by Simone Martini (Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, c. 1330), Funerary Monument to Sir John Hawkwood by Paolo Uccello of 1436 for Florence Cathedral, a fictive statue on a plinth some twenty years before Donatello made a real one. Again, both were of condottieri. The classic exemplar became Titian's magisterial Equestrian Portrait of Charles V (1548), with notable later ones including Anthony van Dyck's portraits of Charles I,[7] and a number by Rubens and Velasquez.

Paintings of horses

Notes[edit]

- ^ Medley, 57-59

- ^ Rawsn, 29-30

- ^ Rawson, 1

- ^ Rawson, 30-31

- ^ Rawson, 31-32

- ^ Two of the 14th century Gothic Scaliger Tombs in Verona were surmounted by rather smaller stone statues.

- ^ Also Charles I with M. de St Antoine and Charles I at the Hunt

References[edit]

- Medley, Margaret, T'ang Pottery and Porcelain, 1981, Faber & Faber, ISBN 0-571-10957-8

- Rawson, Jessica, Animals in art, 1977, British Museum Publications, ISBN 071410082X