User:Jmedi091/Evolution of human intelligence

Adding to Homo Section[edit]

Other accompanying adaptations were the smaller maxillary and mandibular bones, smaller and weaker facial muscles, and shortening and flattening of the face resulting in modern-human's complex cognitive and linguistic capabilities as well as the ability to create facial expressions and smile[1]. Consequentially, dental issues in modern humans arise from these morphological changes that are exacerbated by a shift from nomadic to sedentary lifestyles[1].

History of Humans

In the Late Pliocene, hominins were set apart from modern great apes and other closely-related organisms by the anatomical evolutionary changes resulting in bipedalism, or the ability to walk upright[2][3]. Characteristics such as a supraorbital torus, or prominent eyebrow ridge, and flat face also makes Homo erectus distinguishable. Their brain size substantially sets them apart from closely related species, such as H. Habilis, as we can see an increase in average cranial capacity of 1000 cc. Compared to earlier species, H. erectus developed keels and small crests in the skull showing morphological changes of the skull to support increased brain capacity. It is believed that Homo erectus were, anatomically, modern humans as they are very similar in size, weight, bone structure, and nutritional habits. Over time, however, human intelligence developed in phases that is interrelated with brain physiology, cranial anatomy and morphology, and rapidly changing climate and environments[3].

These developments are organized into three distinct phases of evolutionary changes correlating to human intelligence. The first phase is characterized by the ability to make connections between things, or "causal inferences," especially in regards to hunting and foraging, changes in climate, and general survival in combination with the ability to recognize patterns[3]. The second phase

Tool-Use[edit]

Since early hominins from about 3.5 million years ago are no longer around for direct study, the study of the evolution of cognition relies on the archaeological record made up of assemblages of material culture, particularly from the Paleolithic Period, to make inferences about our ancestor's cognition. Paleo-anthropologists from the past half-century have had the tendency of reducing stone tool artifacts to physical products of the metaphysical activity taking place in the brains of hominins. Recently, a new approach called 4E cognition (see Models for other approaches) has been developed by anthropologist Thomas Wynn, and cognitive archaeologists Karenleigh Overmann and Lambros Malafouris, to move past the "internal" and "external" dichotomy by treating stone tools as objects with agency in both providing insight to hominin cognition and having a role in the development of early hominin cognition[4]. The 4E cognition approach describes cognition as embodied, embedded, enactive, and extended, to understand the interconnected nature between the mind, body, and environment[4].

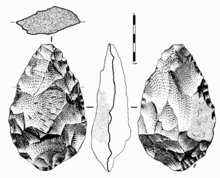

There are four major categories of tools created and used throughout human evolution that are associated with the corresponding evolution of the brain and intelligence. Stone tools such as flakes and cores used by Homo habilis for cracking bones to extract marrow, known as the Oldowan culture, make up the oldest major category of tools from about 2.5 and 1.6 million years ago. The development of stone tool technology suggests that our ancestors had the ability to hit cores with precision, taking into account the force and angle of the strike, and the cognitive planning and capacity to envision a desired outcome.[5]

Acheulean culture, associated with Homo erectus, is composed of bifacial, or double-sided, hand-axes, that "requires more planning and skill on the part of the toolmaker; he or she would need to be aware of principles of symmetry."[5] In addition, some sites show evidence that selection of raw materials involved travel, advanced planning, cooperation, and thus communication with other hominins.[5]

The third major category of tool industry marked by its innovation in tool-making technique and use is the Mousterian culture. Compared to previous tool cultures, which were regularly discarded after use, Mousterian tools, associated with Neanderthals, were specialized, built to last, and "formed a true toolkit." [5] The making of these tools, called the Levallois technique, involves a multi-step process which yields several tools. In combination with other data, the formation of this tool culture for hunting large mammals in groups evidences the development of speech for communication and complex planning capabilities.[5]

While previous tool cultures did not show great variation, the tools of early modern Homo Sapiens are robust in the amount of artifacts and diversity in utility. There are several styles associated with this category of the Upper Paleolithic, such as blades, boomerangs, atatl (throwing spears), and archery made from varying materials of stone, bone, teeth, and shell. Beyond use, some tools have been shown to have served as signifiers of status and group membership. The role of tools for social uses signal cognitive advancements such as complex language and abstract relations to things.

Nutritional status[edit]

Early hominins dating back to pre 3.5 Ma in Africa ate primarily plant foods supplemented by insects and scavenged meat[4]. Their diets are evidenced by their 'robust' dento-facial features of small canines, large molars, and enlarged masticatory muscles that allowed them to chew through tough plant fibers. Intelligence played a role in the acquisition of food, through the use of tool technology such as stone anvils and hammers[4].

There is no direct evidence of the role of nutrition in the evolution of intelligence dating back to Homo erectus, contrary to dominant narratives in paleontology that link meat-eating to the appearance of modern human features such as a larger brain. However, scientists suggest that nutrition did play an important role, such as the consumption of a diverse diet including plant foods and new technologies for cooking and processing food such as fire[6].

Bibliography[edit]

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. April 2022. Major Transitions in Human Evolutionary History. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2021.2018646

Discusses the evolution of genus homo's cognition in terms of six transitions

- Nowzari, Hessam and Jorgensen, Michael. April 2022. Human Dento-Facial Evolution: Cranial Capacity, Facial Expression, Language, Oral Complications and Diseases

Findings show that the hominin ancestors of modern humans underwent morphological and biological evolutionary adaptations that resulted in complex cognitive and linguistic capabilities as well as the ability to create facial expressions and smile.

Such abilities were results of the morphological increase in cranial capacity from the evolutionary adaptation of larger brains. Happening at the same time as the increase in size of the brain, hominins adopted the use of fire and cooking, as homo habilis and homo erectus are documented to have acquired. This may have resulted in a softer diet, evidenced by tooth fossils. Thus, correlating morphological changes resulted in smaller maxillary and mandibular bones, smaller and weaker facial muscles, and shortening and flattening of the face. Consequentially, dental issues in modern humans arise from these morphological changes that are exacerbated by a shift from nomadic to sedentary lifestyles.

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft[edit]

Lead[edit]

The evolution of human intelligence is closely tied to the evolution of the human brain and to the origin of language. The timeline of human evolution spans approximately seven million years,[7] from the separation of the genus Pan until the emergence of behavioral modernity by 50,000 years ago. The first three million years of this timeline concern Sahelanthropus, the following two million concern Australopithecus and the final two million span the history of the genus Homo in the Paleolithic era.

Many traits of human intelligence, such as empathy, theory of mind, mourning, ritual, and the use of symbols and tools, are somewhat apparent in great apes, although they are in much less sophisticated forms than what is found in humans like the great ape language.

Article body[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Nowzari, Hessam; Jorgensen, Michael (2022). "Human Dento-Facial Evolution: Cranial Capacity, Facial Expression, Language, Oral Complications and Diseases". Oral. 2 (2): 163–172. doi:10.3390/oral2020016. ISSN 2673-6373.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Conroy, Glenn C.; Pontzer (2012). Reconstructing Human Origins: A Modern Synthesis. Herman Pontzer (3rd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-91289-0. OCLC 760290570.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Stuart-Fox, Martin (2022-04-18). "Major Transitions in Human Evolutionary History". World Futures. 0 (0): 1–40. doi:10.1080/02604027.2021.2018646. ISSN 0260-4027.

- ^ a b c d Wynn, Thomas; Overmann, Karenleigh A; Malafouris, Lambros (2021). "4E cognition in the Lower Palaeolithic". Adaptive Behavior. 29 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1177/1059712320967184. ISSN 1059-7123.

- ^ a b c d e Shook, Beth; Nelson, Katie; Aguilera, Kelsie; Braff, Lara (2019). Explorations. Pressbooks. ISBN 978-1-931303-62-0.

- ^ Barr, W. Andrew; Pobiner, Briana; Rowan, John; Du, Andrew; Faith, J. Tyler (2022). "No sustained increase in zooarchaeological evidence for carnivory after the appearance of Homo erectus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (5): e2115540119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2115540119. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8812535. PMID 35074877.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ Klug WS, Cummings MR, Spencer CA, Palladino MA (2012). Concepts of Genetics (Tenth ed.). Pearson. p. 719. ISBN 978-0-321-75435-6.

Assuming that chimpanzees and humans last shared a common ancestor about 8-6 million years ago, the tree shows that Neanderthals and humans last shared a common ancestor about 706,000 years ago and that the isolating split between Neanderthals and human populations occurred about 370,000 years ago.