User:Edward Kennedy D. Pero/sandbox

ACTIVITY NO. 3: TRANSFORMING THE CONTEXT OF MANUEL L. QUEZON’S SPEECH INTO HYPERTEXT[edit]

Manuel L. Quezon[edit]

| 2nd President of the Philippines | |

|---|---|

| In office15 November 1935 – 1 August 1944Serving with Jose P. Laurel (1943–1944) | |

| Vice President | Sergio Osmeña |

| Preceded by | * Emilio Aguinaldo * Macario Sakay (1901) * Frank Murphy (1906) * (Governor General) |

| Succeeded by | * Sergio Osmeña * José P. Laurel (de facto) |

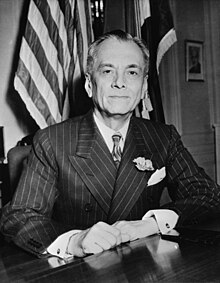

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina, KGCR, also known by his initials MLQ, was a Filipino statesman, soldier and politician who served as president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1935 until his death in 1944 Manuel Quezon, in full Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina, (born August 19, 1878, Baler, Philippines—died August 1, 1944, Saranac Lake, New York, U.S.), Filipino statesman, leader of the independence movement, and first president of the Philippine Commonwealth established under U.S. tutelage in 1935. Manuel Quezon was born to Spanish mestizo parents in the remote town of Baler in Tayabas province, on the east coast of Luzon. His father, a former soldier in the Spanish army, operated a small rice farm, but as mestizos the family enjoyed a higher social status than even wealthy Filipinos

The aspect that took my interest in Manuel L. Quezon's speech is values education in schools.[edit]

I realized a lot of things after hearing Manuel L. Quezon's speech. What is Values Education, according to my understanding? Individuals' character development is emphasized in value-based education so that they can choose their future and deal with challenging situations with ease. It develops the children so that they can adapt to new situations while carrying out their social, moral, and democratic responsibilities effectively. The importance of value education can be shown in its benefits, including developing physical and emotional aspects; the teaching of mannerisms and developing a sense of society; the instillation of a patriotism spirit, and the growth of religious tolerance in students. Let us examine the importance of value education in public schools, as well as its need and importance in the twenty-first century.Values education focuses on improving young people's awareness and understanding of their own beliefs and their relation to the world around them. As a result, it is crucial to try to convey the idea of which values people in our society think are essential and by which our society is shaped today.

Speech of President Quezon on the new policy on education, public works, and clean and honest Government.[edit]

Speech

of

His Excellency Manuel L. Quezon

President of the Philippines

On the new policy on education, public works, and clean and honest Government

[Delivered in front of the Provincial Building in Tacloban, Leyte, June 10, 1938]

Mr. Governor, People of Leyte:

I am happy to be with you here, but I am sorry that you have to get wet in order to hear me. I will not detain you long for we are in the rain.

I know that the people of this province are informed of the purpose of my administration; namely, to give our country a good, clean, and honest government. And I feel sure that of the provinces of the Archipelago that are well governed, the Province of Leyte is certainly one of them. [Applause] I have no doubts that here you have a governor who does not intend to use his office to promote his own interest. Governor Martinez did not seek this position; he was requested by your leaders to serve the province.

I have a man of my absolute confidence who hails from Leyte; that man is your former representative and senator; he is now one of my advisers; but he will very soon leave his post for a better one. I am speaking of Judge Enage. [Applause] There is no man in the Government of the Philippines other than Judge Enage, in whose integrity, honesty, and sense of justice I place greater confidence. I know that in the past you did not always vote for Judge Enage. But I have known Judge Enage in the Senate, and I know that he is one of the best public servants we have in the Philippines. Judge Enage has never abused my confidence in him to prosecute any man from the Province of Leyte. He has never abused that confidence to promote his friends if they did not deserve the promotion. I, therefore, feel certain that you must be having a good government here now because Judge Enage tells me so.

I want to take this opportunity to tell your public officials, from the governor down to the last policeman, that it is my hope and expectation that they will cordially cooperate with me in my efforts to give our country the best government that it has ever had. Particularly, I want them to make the poor man, the man who lives in the barrio, feel that under our Government his rights are as much protected as those of the most powerful or the richest man in the Philippines. So I want every mayor, every councilor, every teniente del barrio, to tell the people that if they have any grievances to make, they must present them to the proper authorities for correction and redress. Particularly, I want the justices of the peace to realize that although they are the lowest officials in the judiciary, yet they hold the most important position. The common man in the Philippines, the man who lives in the far distant barrio, will know whether this is a just government or not only by the manner in which the justices of the peace perform their duties. I want every justice of the peace to know and feel that he owes his position to nobody in particular. It is true that I listened to the recommendations of those who knew possibly the best for appointment to these positions, but I did not appoint the justices of the peace in order that they may serve the interest of those who recommended them, but in order that they may do justice to the people.

I know that in the past your justices of the peace were political leaders. Now, there is no use denying that; I know it; I have been in politics for thirty years. I have forgiven and forgotten every justice of the peace who mixed in politics in the past because that was a fault everybody committed. But we are starting a new book, and, from now on, no justice of the peace must mix in politics except at the risk of losing his job. I want the justice of the peace to have the confidence of the people. I want him to make the people feel that they can go to him and obtain justice. The justice of the peace who does his duties well does not have to kiss the hand of anybody. The justice of the peace who performs his duties impartially, does not need to have political friends. His own protection will be the performance of his duties. But the justice of the peace who mixes in politics and decides questions in favor of his relatives or friends regardless of the merits of the cases at bar, cannot be saved even by the biggest man in the Philippines. [Applause]

I say the same thing about every other government official of the Philippines. Everybody is my friend, but nobody is my particular friend. Every one who complies with his duty is my friend, but nobody who violates the law or neglects to do his duty is my friend. [Applause] I have taken the oath to enforce the laws, and I will enforce them regardless of everybody. [Applause] My duty is to serve the people and the country, to lay the foundations of a Philippines that will live forever and be inhabited by a people who love peace and are prosperous and happy.

Fortunately, we have now at our disposal sufficient funds to start on our program of public works. At its last session, the National Assembly appropriated a vast sum for the construction of our national highways. For the province of Leyte some eight hundred thousand pesos will be spent. I am, therefore, confident in the hope that the people who want to work can be given work in the construction of these roads; and it is my order that the people be given work without considering their political affiliation. [Applause] Those who need work, and want to work, will be given work. This is the instruction that I am giving now to the district engineer of Leyte; he is the official responsible to the National Government in the construction of roads. I expect him to consult the governor and the town mayors in order that he will know the men who need the work most. I want him also to supervise his capataces for I don’t want them to have their protegees. Above all, I don’t want graft in the public works, and I want the governor, the engineer, and every official of this province, to go after the men who are doing some kind of connivance in these public works in order to defraud the Government.

We are going to construct more public buildings, open more schools, and employ additional teachers.

(“Your Excellency.'” shouted a man from the crowd.)

What is your question?

(“Your Excellency: in 1934, the Municipal Council of Tacloban imposed a tuition fee for the intermediate grades. In 1937, although the Municipal Council abolished the tuition fee, yet the Division Superintendent of Schools and the Supervising Teacher of Tacloban have been collecting the fee despite the fact that they have no authority from the Municipal Council.”)

I have here with me the Director of Education, and he tells me that it has not been abolished because the plan of the Municipal Council to abolish it met with the disapproval of the Bureau of Education. I want to be interpreted correctly in this matter. The complaint of the gentleman, on behalf of the Parents’ Association, is that the school authorities are collecting a tuition fee for the intermediate schools. He says that in 1934 the Municipal Council of Tacloban approved a resolution imposing the tuition fee. But, he says further, in 1937 the Council approved another resolution prohibiting the collection of the tuition fee. Now, his complaint is that the Superintendent of Schools continues to collect the tuition fee despite the resolution adopted by the Municipal Council. The Superintendent of Schools claims, and I think he is right, that this last resolution of the Municipal Council of Tacloban had no effect because it was not approved by the Bureau of Education. Now it makes no difference whether or not the Superintendent of Schools has the right to do that. The practice is: if the Municipal Council of Tacloban does not want the tuition fee because the Council can appropriate money from the municipal funds for all the intermediate grades, I will tell the Superintendent of Schools right now not to collect those fees any more. But if the Municipal Council does not want to appropriate the money, and it does not want also the tuition fee collected from the children, I will tell the Superintendent of Schools to close all the intermediate schools in this town.

Now, what do you want me to do? I want the Mayor of Tacloban to answer this question: Do you have enough money to support the intermediate schools here?

(The Mayor: “No, Your Excellency.”)

Do you want the intermediate schools to be kept open?

(The Mayor: “Yes, Your Excellency, but we cannot do that because we have no money.”)

Do you want them open or not?

(The Mayor: “We would like them, but the Municipal Treasurer says we have no money.”)

Call the Municipal Treasurer.

(Addressing the Municipal Treasurer). Can the municipal government pay for all the intermediate schools here?

(The Municipal Treasurer: “Well . . . .”)

That is enough.

I want to tell you this: the National Government is going to assume the responsibility of maintaining the primary schools. Next year we will appropriate the necessary amount for the opening of primary schools in every barrio, and the National Government will pay the expenses of maintaining the schools including the salaries of the teachers. The intermediate schools will be under the responsibility of the municipal government. In other words, from now on, the National Government will pay every cent spent for the primary schools, while the municipal government will be fully responsible for the maintenance of the intermediate schools.

Now, let the people decide what they want: if the municipal government has sufficient income to open all the intermediate schools, it should appropriate the money for the purpose; if it does not have enough money, the people must pay the tuition fee in order to have the intermediate schools. Now, you people decide whether or not you want to pay the tuition fee; if you don’t want to pay the fee, close your schools; if you want to pay, keep them open.

Well, I suppose the tuition fee will not be obligatory. The tuition fee will be paid by the parents of children who want to study in the intermediate schools. But there is one exception to that. If a poor boy or girl proves to be unusually bright and good, the National Government will assume the responsibility for his or her education in the intermediate schools. I can say the same thing now about the high schools. By this, I mean that the academic high schools will no longer be supported by the Government. If anybody wants his child to acquire an academic instruction in the high school, then he must pay the necessary tuition fee.

I will explain to you now the reason for this new policy of the Government. Up to the present, the Government has been committed to the policy of opening all the primary, intermediate, and high schools; but, because there is not enough money to enable us to open primary schools in all the barrios, we have not been able to educate all the boys and girls who wish to attain even only a primary education. The result is that today there are still many illiterate children and grown-up boys and girls. Again, while we have complete primary and intermediate schools in the towns and high schools in the provincial capitals, yet we ordinarily have only one or two grades in the far-distant barrios. As a result of this policy many of the sons of the poor have not gone to any school at all.

So the policy of the National Government now is to open primary schools in all places so that every child of school age, particularly the sons of the poor who live in the farthest barrios, can acquire a primary education. We don’t want to deprive the child of the poor people at least of the knowledge necessary to enable him to read and understand his rights and duties. Now, after every poor boy and girl has gone through the primary school, the question of whether or not he should go to the intermediate school is entirely left to the municipal government. Then the question of entitling him to a higher education becomes the responsibility of the provincial government.

But I don’t want these boys and girls to take the secondary instruction without learning something useful in their daily life. We want to establish a secondary instruction that will be useful to the boy and girl who receive it. Our aim is to increase the people who make their living by producing something that will enrich both themselves and their country.

This is the present situation. Some poor boy finishes the high school course, but he does not know what to do except, perhaps, to be a clerk. He wants to be a clerk, but he can’t find a clerical job. This poor boy worked for four years to earn a secondary education; his parents sacrificed much in order to get him that instruction. Many of them still follow the profession of law or medicine, believing that in the end they could depend on a job for their livelihood. That means another six or seven years more of hard work and sacrifice for their parents. But what is the result? He leaves the university, but he cannot do any work. He has no job; he can’t find one. You have here a disappointed boy with very unhappy parents. They see that their sacrifice did not amount to anything; it did not help their boy or girl after several years in college.

In a final effort to land a job, the poor boy asks a recommendation from the town mayor; he goes to his governor or assemblyman for the same purpose. Then, everybody promises him a job but nobody gives him work. Before the election all promised him a job, but after the election everybody forgot entirely the promise. And the boy or his parents believe that the politician has deceived them. Perhaps, he was recommended to the President of the Philippines; but, let me tell you, the President of the Philippines does not have many jobs to give! Now that poor, disappointed boy becomes a demagogue. He starts his career by attacking everybody in his speeches. He is disappointed; he is unhappy; he thinks that he is not being justly treated.

Well, we have to change that policy. We must educate our boys and girls to be good fanners, good manufacturers, good producers. We have here a big and rich country. All that we need is to know how to make this country produce more.

I will tell you now why Japan, as a nation, is turning to be a success. Japan is successful not because she has a big army or navy. Japan is a very poor country; even the mountains are cultivated. If the Japanese people were to depend only upon their land, they would starve. But the Japanese does not live only on the land; he lives on what he produces through the many industries in Japan. And Japan is competing successfully with Europe and America. The reason for this is that in Japan every man and woman is taught some industry in the school. If the Japanese works in the farm, he makes good because he learned what he is doing. If a carpenter, the Japanese turns out to be an efficient one because he studied the technique in school. In fishing, the Japanese is an efficient fisherman because he studied that work in school. Do the Japanese come here in Leyte to fish? (“Yes, Your Excellency!” answered the crowd.) Now, you can’t compete with the Japanese! Why? Because you do not know to fish the modern way. You know that if we could the Filipinos how to fish we could make this country very rich just from our fish resources. You find out how much a Japanese makes when he goes out fishing, and you will discover to your amazement that he makes more money than a poor Filipino lawyer. Some of our lawyers can hardly make one hundred pesos in a month; but the Japanese fishermen who come here make more than that sum in the same period.

This is the policy that we will adopt. We will teach our countrymen to be good fishermen, good carpenters, good farmers, and good producers, to enable them to make more money than the ordinary lawyer.

Now, my friends, I have talked more than I expected to. I want you to know that it is my desire to extend all possible help and coöperation to your governor and Board. Leyte is one of the promising provinces of the Philippines. It is unfortunate that one of your products here—hemp—has gone down in price. In its last session, the National Assembly passed a law designed to help the hemp industry. Although I am not sure that the bill will remedy your situation, yet I will approve it in an effort to do something to help the hemp industry in the Philippines. We must do something for this very important industry. I want you to feel certain that if possible I will do all I can to bring about a relief to this industry.

My friends, I am happy to see you here, and goodbye to all.

Speech President Quezon on reforms in the Public School System and cooperation of school teachers with the Government.[edit]

Speech

of

His Excellency Manuel L. Quezon

President of the Philippines

On Reforms in the Public School System and Cooperation of School Teachers with the Government

[Delivered during the luncheon given in honor of division superintendents of the Bureau of Education at Recreation

Hall, Malacañan Park on December 10, 1939]

Gentlemen:

I have found that illiteracy is spreading- despite our system of public instruction and the increasing number of schools that we have. There must be a defect in our system. A cause must exist why we have not accomplished as much in the field of education as in other fields, considering the number of students that we have. My belief is that the fault lies in the National Government.

I have repeatedly stated that we have the most perfect government on earth in the Philippines; in fact, the best government in the world on paper. If you see our official reports you will say, “Why, this is marvelous.” Everything has been properly attended to on paper. But when you come to analyze exactly what we are doing and the practical results that have been accomplished so far, you will find that seventy-five per cent of that magnificence in our government is bunk. In the reports you even find the number of agricultural schools. You go to these schools and you will find that the students have not learned anything practicable. Take the experimental stations of the Bureau of Plant Industry. The reports are wonderful! But visit them, and you will find out that these stations are neglected.

Several years ago I visited an agricultural school in Isabela. What did I find? Nobody was there. The man in charge of it was in Manila. Somebody was there to take care of a few implements. A little shack stood, together with a small camarin, in the midst of several thousands of hectares of land. I asked the boys attending that school if they have finished their course, and they answered me in the affirmative. I asked them the way to plant tobacco, and they explained to me the very method which their forefathers, were they still alive, would have instinctively used. That is not your fault. It is the fault of the Government which permits the establishment of these schools without giving them the necessary funds. For instance, the Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce asked the National Assembly to pass a measure which would establish an experimental station in Bataan and appropriate P50,000 for the purpose. The National Assembly authorized its creation and gave him only four thousand pesos for it. With that amount, what could the Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce do?

Our mistake lies in this point. The Bureau of Education or the Bureau of Plant Industry goes to the Assembly and says: “We want to establish agricultural schools or experimental stations and would like to have an appropriation of one hundred thousand pesos.” If you desire to have a school that is fully equipped to teach the science of modern agriculture to its students, you have to get such amount of money. If the National Assembly reduces the appropriation, it would be much better to refuse to accept the amount than to establish the school, for by so refusing the National Assembly will know that the money appropriated for that purpose is not sufficient.

But what happens usually? A bureau chief recommends to the National Assembly by the establishment of a service, say, an experimental station. He says he needs twenty-five thousand pesos for the purpose. Instead, the National Assembly gives him only five thousand. Then the director says: “Well, that is all right.” In such case, they give the National Assembly the impression that they have asked more money than what they actually need. What should really be done is to have the Executive Department ask for the amount actually needed.

I do not read the reports of the Director of Education, even if I want to, because I have no time to do so. But I take it for granted that whoever is specially detailed to do that job would call my attention to some important things that I should know.

It was only this year that I found that we have over-expanded our school activities. Seeing that the National Assembly has been appropriating too much money for schools even before we knew exactly what to do, I asked for information on the situation. For the first time I discovered that in view of this very rapid expansion, we have not been able to acquire the right kind of teachers for our schools.

According to Director Salvador, the standard of our public education is going down. I do not desire to find out who should be blamed in particular, but it would be more Christian-like if I say that it is the fault of all. We can say publicly that we have more schools now than before. But educational results and accomplishments should justify the expenditures of an enormous sum of public funds. You spend one hundred thousand pesos to educate ten thousand children, but the result is that you have educated only two boys and two girls. On the other hand, for twenty-five thousand pesos you can educate ten boys well. Certainly, you have done better by spending twenty-five thousand pesos to educate all the ten boys than by spending one hundred thousand pesos to educate only two boys and two girls out of ten thousand children. That is common sense. I do not have to be an educator. Herein lies the defect of our system.

I am not interested in the number of schools. But I am interested in the results obtained from having so many schools. If, as the Director of Education told me, our standard of education is going down, then we had better close the schools. Otherwise, do not expand them any further until you can keep up the educational standard with the present number of pupils. He also told me that the expansion of the schools is necessary because of the clamour o the people to have their children enrolled, and that the National Assembly insists upon appropriating more money for schools. Of course, our people have reason to ask for more schools. The assemblymen also appropriate more school funds because such appropriations mean more votes for them. But the Executive Department has the responsibility of rendering satisfactory and efficient service to the people, and not finding votes for the members of the National Assembly.

Some people believe that you can erect a school building out of bamboo, where the children can go and be taught by somebody. That which happened during the Spanish regime was, of course, all nonsense. I myself attended the public schools. The Department of Public Instruction, rightly or wrongly, has given the people the impression that by building these schoolhouses, they can attend school; and, because we did not want the people to lose faith in the Government, we authorized the establishment of these schools. Nevertheless, I have always instructed the Secretary of Public Instruction to appoint schoolteachers who are at least high school graduates and who can satisfy him that he or she is a material that could be developed.

From a recent report of the Director of Education, I found that he attributes the lack of teachers to the low salaries paid them. I do not agree with him in that respect. That does not mean, however, that I do not believe in giving the teachers better salaries. I think we have a sufficient number of schools in the Philippines which are provided with adequate teaching personnel. Besides, our people are in a desperate economic situation that thousands of young men and women would be willing to teach even at the present salaries of the teachers. I do not mean that we are already paying them adequately under the present scale, but I do mean that there are enough young men and women who can give the Philippines all the teachers that may be needed without the necessity of increasing their salaries. What I will say now is a practical situation. Children of the poor class who are normal school graduates would find themselves safe from starvation, if we could appoint them as teachers even at a low salary. When you speak of the salary to be paid to public school teachers, what should be considered is the relative position of the individual who is to receive that salary.

If we consider the earning capacity of the average citizen, you will note that we have been paying high salaries in the Philippines. It is one of the things that we have learned from the Americans. It is the fault of the American Government in the Philippines. We have been accustomed to either pay or receive those salaries. The American people have an economic standing that can well afford to pay those high salaries, which are also paid in the Philippines notwithstanding the economic situation of the country. But this should not be the basis for the salaries we are to pay. Considering the standard of living here, the Filipinos should receive lower salaries than the Americans. But the Filipinos retort: “That is racial discrimination. Why should they be given high salaries when the money paid to them comes from the Filipinos?” That was the practical situation that confronted the American teachers before.

On the other hand, if the Filipinos take the place of the Americans, they demand a salary equal to that of their predecessors; so we have created a standard of living for our public officials that is way beyond the capacity of our Government to support. A remedy to this would be to reduce the salaries of those who are highly paid, but the pressure is toward increasing the salaries of those who are meagerly paid. If we raise the salaries of school teachers, we will have to close many schools.

Many teachers thought that they were the victims of discrimination when the pension system was abolished. But from its first day of existence that pension system was already in a state of bankruptcy. Why? Because it was given a retroactive effect, so that those who had served twenty years received the benefits of that system even without contributing anything to it, while the poor teachers who were now in the service suffered the injustice. Naturally, the system was bankrupt from the beginning. What should have been done was to pay pensions on the basis of the contribution paid. But that was not done.

The Department of Public Instruction should study in detail the means of increasing the salaries which the Director of Education has requested for the school teachers, by considering not only the present number of schools but also the number of teachers. We have already started increasing the number of schools. The Constitution ordains that the Government should make every effort to give all children of school age an opportunity to attain at least primary instruction. In this connection, this question should be studied: what would be the increase in the number of schools as demanded by the increased number of children of school age, and on this basis what should be the increase in the salaries of teachers?

I do not want the Director of Education to state again in his report that the salaries of the teachers should be increased, unless he is prepared to state definitely the total expenditure for the whole system of education in the Philippines. It is all right to ask for more funds if you know at least the ultimate financial responsibility the system would entail. But you cannot do that unless you know where you are going. When the Director of Education is prepared to inform me—and he should know it—on the increase in the school population year after year during the next ten years, the number of schools and teachers to be required due to this increase, as well as their meaning in terms of pesos and centavos, and what it would mean if any increase in salary is put into effect, then the whole thing may be considered. In fact, the Government of the Philippines has been spending all it can afford for the education demanded by the people.

The other day when I was discussing the amendments to the Constitution with the provincial governors, one of them said: “Mr. President, if you want to have these amendments pushed through, promise the people more schools.” I answered him: “No, I am not going to do that. I am not interested in becoming popular. I am more interested in letting the people know the truth and doing for them what I really can do. I am more concerned about the service that I can render to our country than about my popularity. I will not get the applause of the people through deceit or waste of public funds.”

I can authorize the establishment of a schoolhouse for every family in every village of the country. But I will only do that if I have the teachers, the books, and the implements necessary to give the children the instruction that they should receive. That is my way. I will only permit the establishment of schools if we can make the parents believe that their children would not be wasting their time by enrolling in them. That is why I will not increase the number of schools until I am aware that the Government is in a position to give real schools.

You know that I changed the Government’s policy of not authorizing the construction of schools unless they be made of cement or of strong materials. It is not the kind of materials used in the construction of a school that produces results. It makes no difference to me whether the school-house is made of bamboo, cement, gold, or silver, provided that the children therein are amply protected from both rain and sun, have plenty of fresh air, and are properly seated. What counts most is the quality of teachers.

Gentlemen, I want your coöperation on the things that I want to say now. It will be much better for us to have less schools and less children if we can only increase the literacy of the people, rather than have many schools without producing results. But above all, I am interested in getting boys and girls who are capable of doing something, and who understand life and its responsibilities. The problem of our Government is to give practical education to our children. They should be inspired to do things which their parents are doing. I hope that such would be the mental attitude of the children now in school. I wonder if these children have learned to love life on the farm. It is human nature to instill in the hearts of our young men and women who go to school the love for life on the farm, provided that such life will not mean an idle life spent in sleep, but a life as lived by their parents. That is why I am so much interested in getting a better living for the kasamas or hacienda men, although it will take time to accomplish it.

I am, however, afraid that I am accomplishing one very undesirable result in this line, for I see that these poor kasamas are now taking the law in their hands. That is why the Government is going slowly in the enforcement of its laws. This brings me to a point of the subject I am discussing.

You know, teachers can be made a powerful factor in helping the Government in this respect. I want the teachers—I told Secretary Bocobo and Director Salvador about this—to live the life of the community. I do not want them to consider themselves apart or independent of the everyday life of the community in which they live. I do not want them to consider that their work is done as soon as they leave school or that their work is just to teach. They should take interest in the activities of the children and their parents, in connection with a study of their mental and emotional reactions. Of course. I do not want them to be involved in politics; I told you that many times. But they should take special interest in public questions. Although politics and public questions are almost similar, yet they are two different things. When I speak of politics. I refer to the partisan side of a question, such as finding out whether you are an Osmeñista or a Yuloista. That is not the business of teachers. I want them to study and find out what is going on, what is to be done, what the Government is trying to do; and not simply say “yes” to what the Government is doing.

Speaking of criticism, it would be a good way if these teachers put down their opinion on certain things that we are doing in letters to their superintendents, who, in turn, should write about them to the Director of Education. That would be a magnificent way of knowing the reaction o the people to our policies. I do not believe that it would be good for them to go out and criticize our policies; instead, they should frankly and honestly express their opinion on the things that are being done. The teachers are our greatest help in reporting any injustice being committed by some crooked officials in the community. That is one way of rendering service and showing interest in the community. If a municipal mayor is a crook and he abuses the people, the teachers should report the matter to the proper authorities, but they should not make any public charge against that official. Of course, we should be careful in finding out whether or not the teacher is against him. Only the spirit of service should animate the teachers in rendering this particular public duty.

I have been told by members of the National Assembly that generally the teachers are antagonistic to the Government. If this be a fact, we should know the reason. I cannot believe that the teachers, like the Irishmen, are going against the Government, because if all the boys and girls who come out of school under your direction are against the Government, then we would be creating a government of anarchists. If that is the attitude of a few teachers, then they are perhaps guided only by selfish motives. I saw some of these teachers—men and women— and when I looked at their faces I could almost read what was in their hearts. There was nothing in their facial expression that revealed an unbalanced mind and a prejudiced heart. I did not see that. On the contrary, they are so simple and so willing to do something—nay, anything.

If the teachers are against the Government because of their present salaries, then it is a question of explaining to them the present situation of the Government. I do not believe that we should sacrifice the finances of the country because a few teachers wanted to have a few pesos more. Of course, that is simply being human, but that consideration alone should not make them antagonistic to the Government. Now, some of them may ask, ”Why do the members of the National Assembly increase their salaries?” Well, there is a good reason for that. We must, therefore, concern ourselves with the instrumentalities through which our Government can reach the people and vice versa.

Once more, I want to say that I am not interested in personalities, much less in parties. By that I mean I am not interested in personalities or in parties to the extent of considering them of great importance. I do not, of course, deny that I possess the natural preferences of a human being for his associates. I have my natural affection for my own political party, but I have a much broader affection for all. My interest is to have a government in the Philippines that will do justice to all our people—a government that will win the confidence and faith of our people. I am interested in having an individual get the support of the people, for once the people lose their faith in their government, they will destroy that government. On the other hand, if they lose faith in one individual, they can simply change him. But they must have faith in our political institutions so that they will support them. Of course, they will have faith in the Government if they see it doing justice to all.

It is, therefore, important that we should let our pupils know that what the Government is doing is not unjust or unfair to anybody. You, gentlemen, can do a lot. As a matter of fact, you are more duty-bound than any other official of the Government to help in our present work of creating a stable government here, and to instill on the minds of our people the realization of the tremendous responsibility that is ahead of us.

Gentlemen, I want your teachers to know that ours is not a fine situation today. While there is contentment among the rich elements of our population, yet there is a great discontent on the part of the lower class. At any time, we can have this small country converted into another Spain. But that is not likely to happen during the next five or six years. I do not foresee that because the United States is still here. I want you to know that independence is coming in 1946, despite McNutt and Romero. That is settled, so make up your minds. There is nobody who knows what will happen to the Philippines better than Manuel L. Quezon. And I am telling you what I know to be a fact: independence will come in 1946, reexamination or no reexamination. Many of our people do not take this seriously, because they believe that something may happen yet. I know that many do not want to have independence in 1946, precisely because of these responsibilities which I am discussing today. But it is coming, whether they like it or not—independence in 1946! The Philippines will be independent in 1946, even if the Philippines goes to the rats. So, what we have to do now is to bear in mind what will follow after independence is granted, for the situation will not be as safe as it is now.

I am sure you do not want to hear shooting somewhere one day while you are in bed. Nobody wants that. You, fellows, can help a lot to avoid that. Get your teachers to preach to their boys and girls on the necessity of maintaining peace and order. Use your teachers to counteract the effects of the irresponsible preaching of demagogues. Do it that way. Let the teachers take interest in their pupils and make them live the life of the community, so that the people may—through those teachers—see that the Government is interested in making them feel that they are a part of the Government and not aliens to it. Admonish your teachers not to be antagonistic to the Government and make them understand that if the Government were to go to pieces they themselves would go to pieces.

As I said once, these people who are preaching social justice are getting far ahead of me. I listened to a wonderful oration delivered at an oratorical contest held last night. As I listened to Manglapus, every fiber of my being was touched. That is the effect of what I am saying: these fellows are going a little bit too far. And if that speech were delivered in the native dialect before the tenants of Nueva Ecija or Pampanga, you can be sure that there would be a revolution the next day. Just imagine, he said that people have been robbed of their lands. Then he pointed out how these lands came into the possession of the encomenderos. Of course, this took place during the Spanish regime. All these ugly things were said by Manglapus, who was educated by the Jesuits and the Jesuits were the ones who were believed to be responsible for the robbery of these lands. [Laughter.]

Just three or four days ago, I went to investigate the complaint of the tenants of Guadalupe Estate. They have been living in that place since time immemorial; their ancestors had also lived there; yet these tenants have been required to pay from two to four pesos per square meter for the land which they occupy. This hacienda belongs to the Augustinian order. A historical marker in the Church of Guadalupe states that it was built in 1560—a few years after the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines. Evidently, those Augustinian friars took a banca and glided along the river until they saw that place and decided to stay there; and the friars became the landowners. Certainly, these tenants are the owners of the land, and yet they now find themselves aliens to that land. So when I heard Manglapus deliver that magnificent speech, I was surprised. Those Jesuits should not have permitted that boy to denounce what the friars did. They knew what the speech was and still they allowed him. And the boy was no fool—he prefers to mention “encomenderos” instead of “‘friars” although those words mean the same thing. And they tell me that this Manglapus is a son of a rich father. If we can get several young men like Manglapus and have them deliver that speech, we will surely have a revolution in the Philippines.

The Government cannot allow the people to take the lands belonging to others and then subdivide those among themselves. We have to defend the rights of those who possess Torrens titles. I f you allowed people to grab another’s lands which they could subdivide, they would not care whether the lands belonged to a friar or to a Filipino. If a man working in an hacienda for a Filipino sees the other fellows working in a land owned by a friar take the land and subdivide it among themselves, he would also insist on subdividing the hacienda of the Filipino. He is not interested in the land’s ownership. If the Government, therefore, permitted a piece of land owned by a certain man to be divided, the other fellows would do the same.

The Government will not defend atrocities committed three hundred years ago. We have no money to expropriate them all. I cannot carry the burden of buying these lands and subdividing them among some tenants in certain provinces, because the rest of the country will not be benefited by that. If that were the case, a taxpayer in Ilocos Norte, where there are no haciendas, would be paying heavy taxes to enable the tenants in Nueva Ecija to obtain a piece of land free. We could do what the Mexicans did; that is, take over the ownership of the lands and give them to the people. But we could not do that as long as we have this kind of government here.

So, as I have said, this movement is going too far. I must tell you, however, that I have to stop this, because I cannot tolerate the situation. But I want you to know that when I start doing that, it would be like setting fire in a prairie, as every man and woman has a sense of justice in his or her own heart. What had been denounced was true. But our youths seem to be quite irresponsible for they take only one side of any question. They are now criticising me for talking too much and not accomplishing much. They do not see the realities of life; they do not see the things to be done in order to do more good than evil. I could easily start social reforms in twenty-four hours, but that would surely mean destruction to the people. You do not want to have a revolution here. What I am trying to do is to accomplish something in the Philippines which has not been accomplished in any other country; that is, to bring about social reform here without bloodshed.