User:Bleff/sandbox8

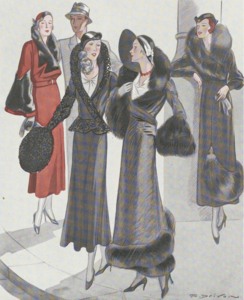

Western fashion in the 1930s was characterized—in womenswear—by a departure from the boxy, boyish look from the previous decade in favor of a more mature and feminine silhouette, with the return of natural waistlines and a heightened emphasis on glamour, elegance and sophistication.[1][4] The era is well framed by two major world events: the 1929 Wall Street Crash, with the ensuing Great Depression that lasted until the end of the decade; and the onset of World War II in 1939. Since they are situated between the "roaring" era of the 1920s and the period of war-induced austerity of the 1940s, the 1930s are often overlooked in fashion history discussions and reduced to a mere transitional era.[4][5][6] Nevertheless, the 1930s saw many changes and innovations in fashion design, technology and consumer culture, and has been referred to as the "Design Decade" both contemporaneously and in modern times.[5][7][8] The period was also one of expansion and consolidation of the Hollywood film industry and its star system, which became a key actor in the setting and dissemination of fashion trends, a role hitherto dominated by the haute couture centered in Paris.[1][2][3]

Although the 1930s were considered a period of great modernity in clothing, the new styles were defined by a reinterpretation of the past.[9] At the beginning of the decade, the neoclassical style—so called because of its ancient Greek influence—emerged and defined the look of the period, which highlighted the natural female figure through the innovation of the bias cut.[9][10] Pioneered by couturier Madeleine Vionnet, the technique consisted of cutting the fabrics at an angle instead of in a straight line, which made them drape smoothly over the woman's figure.[9] This meant that for the first time in the history of Western fashion, dresses skimmed to the body without any sculpting underlayer.[10] Other styles that characterized the decade were romanticism, which recovered elements of Victorian fashion; and surrealism, epitomized in the work of designer Elsa Schiaparelli.[9][10]

Some of the leading fashion designers of the 1930s include the French-based Vionnet, Schiaparelli, Madame Grès, Jeanne Lanvin, Edward Molyneux, Jean Patou and Robert Piguet;[11] the British Norman Hartnell and Victor Stiebel;[12] and the Americans Hattie Carnegie, Jessie Franklin Turner, Nettie Rosenstein, Valentina, Sally Milgrim and Elizabeth Hawes, among others.[13][14] The most influential costume designer of Hollywood was Adrian, with Orry-Kelly, Travis Banton, Walter Plunkett and Dolly Tree also being prominent.[14][15] The decade was also the heyday of fashion illustrations,[16][17] as well as a time of great growth for fashion photography, with influential figures like Edward Steichen, George Hoyningen-Huene, Horst P. Horst, Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Cecil Beaton, Martin Munkácsi, Erwin Blumenfeld, George Platt Lynes and John Rawlings.[18] Some of the female fashion icons of the era include Hollywood stars such as Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Marlene Dietrich, Vivien Leigh, Katharine Hepburn, Jean Harlow, Carole Lombard and Ginger Rogers, as well as socialites like Daisy Fellowes, Mona von Bismarck, Barbara Hutton and Wallis Simpson, who rose to fame for her relationship with King Edward VIII, a style icon in his own right.[19] Other menswear fashion icons of the 1930s were also Hollywood stars, among them Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, James Stewart, Cary Grant, Fred Astaire and Errol Flyn.[20][21]

Women's fashion[edit]

General trends[edit]

que paradoja https://exhibitions.fitnyc.edu/fashions-of-the-1930s/#grid-page As noted by fashion historian Emmanuele Dirix:

Usually in times of economic downturn a more restrained approach to fashion can be observed, especially in terms of hemlines. (...) It would be logical to assume that hemlines rose in the 1930s, but they did nothing of the sort until its closing years. One could also have expected fashions to be more restrained and conservative against this backdrop of rising right-wing politics; again, however, logic and history collide, as decadent glamour ran riot. This is what is so intriguing about a fashion study of the 1930s—it allows us to see that whilst fashion may be inextricably bound up with culture, the way it influences and is influenced by the world is neither obvious nor overtly logical. To understand fashion one not only has to look at the culture that produced and consumed it, but one also has to be able to 'read' the garments themselves."[5]

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/05/the-way-we-look-now/359803/

https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/discover/2015/02/26/womens-fashion-in-the-1930s/

https://screenarchive.brighton.ac.uk/portfolio/screen-search-fashion/1930s-fashion/1930s-womenswear/

http://www.magicasruinas.com.ar/revistero/argentina/argentina-moda-30s.htm

https://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1359?lang=en

Body ideal https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/38932032.pdf

glamourrr[23]

As noted by fashion historian Emmanuelle Dirix:

This more womanly appearance is often ascribed to the changes brought abot by the Great Depression—the clear signal that the Jazz Age party was over. However, closer study reveals that this look was not so much a break with the past as a clear progression from the changes afoot in late 1920s fashion. The flat, almost cubist silhouettes of the early Twenties developed into more figure-hugging shapes in the second half of the decade. By 1927–28, dresses once again followed the natural contour of the body and clung closely to the hips, owing to the insertion of diagonal waist panels. The waistline, which had been absent in the opening years of the decade and which had later reappeared (albeit dropped a few inches), returned more or less to its natural position by the end of the decade. Hemlines (which slowly and progressively crept up, reaching their highest point in 1925–26) dropped again in 1928, often through the addition of floating panels at the back and side of skirts and dresses. So even before the Crash, the main features of what we now remember as a typical 1930s silhouette were already in place".[5]

Although the decade saw the return of natural waistlines and longer hemlines and sleeves, fashion historian James Laver noted that "there is no exact parallel between the fashions of the early 1930s and those of a century before, for the waist did not become excessively tight and the general lines of the skirt remained more or less perpendicular."[24]

Although the Art Deco style is generally considered to have reached its peak in the 1920s, it continued into the 1930s as an element of the "modernist aesthetic" that was popular in clothing and textile design.[25]

The ballerina skirt—a "wide skirt, often of several layers of light fabric, of mid-calf length and inspired by classical ballets"—was especially popular during the 1930s.[26]

A very important trend of the early 1930s was the so-called bias cut, which involved "cutting fabric on the bias at a 45 degree angle on the woven fabric against the weave".[1][27] The bias cut was championed by French designer Madeleine Vionnet in the 1920s and, by the early 1930s, it became a popular style for creating garments that lightly hugged a woman's curves, contributing to the overall slender look of the era.[1][27] In particular, the body-skimming style dominated eveningwear, characterized by satin dresses with low backs that hugged the body's curves and flared at the bottom, creating a "fluid and feminine silhouette".[1][27]

Early in the decade, the predominant fashion trend was the so-called neoclassic style, which drew inspiration from classical Greece.[22] Neoclassical fashion was defined by "white and ivory columnar bias-cut evening dresses [that] often featured Greek details such as cowl or cascade drapes."[22] Fashion publications compared garments to Greek architecture, while editorials frequently juxtaposed models with ancient columns and sculptures.[22] One of the most notable proponents of this style was French designer Augusta Bernard, who was known for her expertise with the bias cut.[22]

The Argentine fashion magazine Para Ti celebrated the departure from the 1920s style in an October 1934 article: "Happily, the strange ghost of the fashion of the film actress type who was admired due to bad taste has passed, worn out in search of a new ideal of modernity. Ever since the pale-skinned, sickly-looking, anemic type of woman dreamed of in the romantic era, we have seen many different kinds of skinny women. All these shadows have disappeared, and we have finally found the balance, the luminous beauty of harmonious lines, far from all extremes. To find elegance and beauty in a skeleton was a real aberration."[20]

Wallis epitomized the new "hard chic" style of the decade.[28]

The greatest textile innovation of the decade was nylon, which appeared in 1939 and revolutionized hosiery.[18]

"Gibson Girl" revival.[29]

Adrian's white mousseline de soie gown for Joan Crawford in the 1932 film Letty Lynton is widely credited with starting the trend for "romantic nostalgia".[30] As noted by the Smithsonian's Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style: "Robes de style (with loose bodices, dropped waists, and full skirts) had preserved prettiness and the traditional idea of femininity throughout the 1920s. Now diaphanous concoctions trimmed with an abundance of frills, ruffles, and lace became popular with those too young, too old, or not streamlined enough to squeeze their bodies into an unforgiving lamé or satin sheath."[30] This new wave of romanticism was boosted by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth's state visit to Paris in July 1938.[31] Known as the "White Wardrobe", the famous series of romantic gowns she wore during the visit were based on the paintings by Franz Xaver Winterhalter.[30] Reflecting on the romantic fashion of the 1930s, Cecil Willett Cunnington wrote in 1952: "Never has Fashion been more ironic than in this attempt to revive, for an evening dress, the modes current on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War."[31]

In the summer of 1939, a reported from Vogue noted the wide variety of models offered by the leading fashion houses: "Nothing varies more than silhouette. You can look as different from your neighbour as the moon from the sun—and both of you are right. The only thing that you must have in common is a tiny waist, held in if necessary by super-light weight boned and laced corsets. There isn't a silhouette in Paris that doesn't cave in at the waist."[31]

The film industry, especially that of the United States, had a great influence on fashion during the 1930s, with women embracing the glamourous styles featured in Hollywood movies.[1] Actresses such as Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and Bette Davis became some of the first style icons of Hollywood and had a direct influence on fashion,[1] beginning to replace the traditional role of the upper classes as leading trendsetters.[2]

"Hollywood's ascent in the fashion industry was helped because designers had to create outfits that looked ahead of the trend by the time the movie was released. The fashions were then copied by retailers and American design started to move away from Paris".[3]

A white cotton organdie gown worn by Joan Crawford in the 1932 film Letty Lynton.[3]

https://www.marieclaire.co.uk/fashion/1930s-fashion-the-women-who-defined-thirties-style-78149

"We, the couturiers, can no longer live without the cinema any more than the cinema can live without us. We corroborate each other's instinct."[3]

— Lucien Lelong, 1935.

Anna May Wong—the first Chinese American Hollywood star—was regarded as one of the best-dressed women in the world, although her outfits were unconvential, combining current Western fashions with traditional Chinese dress.[32] She was especially associated with the cheongsam dress, which she helped popularize as a staple.[32] Her hairstyle was also widely imitated, featuring straight-cut bangs.[32] Wong may be considered the first fashion icon of Asian descent, and is said to have "opened the door to more inclusive standards."[32]

-

Evening coat by Revillon Frères made of fur, 1930.

-

Evening dress from France made of bead-embroidered silk, c. 1930.

-

A young typewriter in the Netherlands, 1931.

-

An opera cloak from France made of silk velvet, embroidered with beads, sequins, and rhinestones, 1931.

-

English aristocrat Diana Mosley, 1932.

-

Evening coat by Jeanne Lanvin made of wool and fur, 1932.

-

A group of women at a horse race in Brisbane, 1933.

-

A group of working women leaving the factory in Buenos Aires, 1933.

-

Portrait of a young woman in Romania, c. 1930s.

-

Evening jacket by Jeanne Lanvin made of silk, fur and metallic thread, 1936.

-

Portrait of a lady by Bernard Boutet de Monvel, 1936.

-

Romantic-style dress by Jeanne Lanvin made of cotton and silk, 1937.

-

A woman attending a race at the Randwick Racecourse in Sydney, 1937.

-

Evening dress by Bergdorf Goodman made of silk, velvet and metallic thread, 1937

-

Farouk of Egypt with his mother and sisters, 1938.

-

Two women in Budapest, 1939.

-

Marlene Dietrich in the 1930 film Morocco, wearing her signature masculine attire, featuring a white tie and top hat.

-

Joan Crawford in the 1932 film Letty Lynton, wearing the influential chiffon dress by Adrian that created a craze for similar designs.

-

Barbara Stanwyck in the 1933 film Baby Face, wearing a nightgown designed by Orry-Kelly that features a plunging back.

-

Asian-American fashion icon Anna May Wong in the 1934 film Limehouse Blues, wearing a reintepretation of the Chinese cheongsam designed by Travis Banton.

-

Carole Lombard in the 1935 film Rumba in a Travis Banton design, showcasing the neoclassical aesthetic of the decade.

-

Ginger Rogers in the 1936 film Swing Time, wearing a silk nightgown and matching cape designed by Bernard Newman.

-

Nina Mae McKinney—one of the first African-American Hollywood actresses—c. 1936, wearing hoop earrings and a floral print ensemble.

-

Katharine Hepburn during the filming of the 1938 film Bringing Up Baby. She pioneered the use of pants on women and helped popularize them.

-

Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford and Rosalind Russell in the 1939 film The Women, wearing nightgowns designed by Adrian

Sportswear[edit]

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2016/02/160202_cultura_pijamas_moda_finde_vs

-

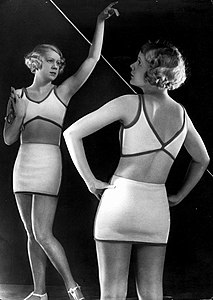

Fashion shoot for bathing suits photographed by Yva, c. 1930.

-

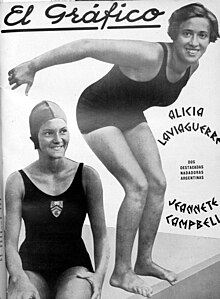

Argentine swimmers Alicia Laviaguerre and Jeannette Campbell in El Gráfico magazine, 1931.

Accessories and shoes[edit]

In the 1930s and its Great Depression context, fashion accessories were seen as an inexpensive option to elevate and modernize an existing outfit.[33] The 1930s witnessed a shift in accessories towards abstraction, showcasing bold geometric patterns

Hats were a vital element of a woman's wardrobe in the decade, and thus received more editorial coverage than any other type of accessory.[33] The 1930s marked the end of the dominance of the tight-fitting, deep-crowned cloche hats that defined the previous decade, being replaced with a wide variety of designs.[33][34] Vogue magazine declared 1931 as the "Great Hat Year" because of the variety of novel models and the fact that "they were a considerable factor in stemming the tide of depression that was another phenomenon of that momentous year."[33] The choice of headgear allowed women to update or add formality to an outfit, as well as reflect their personality.[33] Hollywood stars were a major influence in popularizing new hat styles, especially Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich.[34] The Gilbert Adrian-designed hat worn by Garbo in the 1930 film Romance, known as the Empress Eugénie hat, "set off a nation-wide buying craze, as did the wide-brimmed slouch hat that Garbo would wear to hide her face."[34]

To complement the new "diagonalistic" and body-hugging shapes of the fashionable bias-cut clothing, various styles of hats were designed to be worn at different angles over the head and forehead, evoking the movement of the gowns as well as some styles of men's hats.[33] As noted by Colleen Hill: "By the early 1930s, newly 'masculine' hat styles began to make regular appearances in fashion editorials. Sometimes resembling a man's bowler, other times paying closer homage to the fedora, they shared a quality of casual elegance, and could be paired with almost any daytime ensemble. (...) Rarely were any of these hats mere copies of menswear styles, however. Although not as severely modern as the cloche, their intricate folds, tucks, and stitching techniques were fresh and subtly complex."[33] Although no single initiator of this trend can be identified, as early as the 1920s several manufacturers of men's felt hats began to offer models for women in response to the popularity of cloche hats[33] By 1936, a noticeable shift occurred in hat trends, as the once prevalent simple, masculine styles made room for designs boasting strikingly different silhouettes.[33] Fashion editorials showcased hats with exaggerated crowns, some lavishly adorned with draped fabrics or intricate trimmings, while others seamlessly integrated elements of earlier streamlined designs with the fresh silhouette.[33]

The 1930s saw the return of trimmings such as flowers and feathers in millinery after their near-disappearance in the second half of the 1920s.[33] Nevertheless, they were "markedly simpler than the elaborate embellishments seen on hats prior to World War I."[33] The decade also marked the emergence of prominent American milliners such as Lilly Daché, Mr. John and Sally Victor, who appeared in fashion magazines alongside French designers.[34] Mr. John designed various iconic hats for Hollywood films, notably a veiled cloche worn by Dietrich in Shanghai Express—which made veils popular nationwide—and the famous cartwheel hat worn by Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind (1939).[35] However, the designer who most epitomized the 1930s was Schiaparelli.[36] Some of her most emblematic designs of the decade were the "Mad Cap", which consisted of a "simple knitted cap that could be twisted into a variety of shapes"; and her 1935 doll hat, which "perched whimsically on the front of the head and was secured by a band, elastic, or a snood" that "covered and contained the hair on the back of the head".[36] Schiaparelli was known for often incorporating surrealist influences into her headgear designs, such as hats in the shape of inkwells, baskets of flowers or lamb chops.[36] One of her most iconic designs was the "Shoe Hat" made in collaboration with the surrealist Salvador Dalí, which "looked like a high-heeled shoe worn upside down on the head."[36] The influence of Schiaparelli's surrealism was picked up by Hollywood, such as in the "tower" hat worn by Garbo in Ninotchka (1939).[36]

Buttons had a great importance among fashion accessories during the 1930s and were generally large or of decreasing size, some featuring surrealist motifs (like cicadas, butterflies and dragonflies), and others made of fabric from the patterns on the dresses.[20]

In the 1930s, there was a wide variety of shoe and heel shapes to choose from, especially by the end of the decade.[37]

Italian designer Salvatore Ferragamo is credited with introducing the platform shoe in the late 1930s.[38]

-

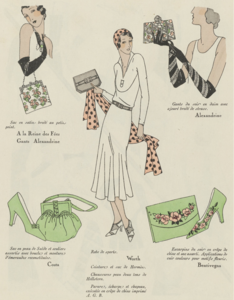

French fashion plate from 1931, displaying several accesories and featuring a dress by Worth in the center.

-

Parisian fashion plate, 1931.

-

Wool hat by Jeanne Lanvin, 1932.

-

German actress Renate Müller, 1932.

-

Swedish actress Dora Söderberg, 1933.

-

Cadanian athlete Alexandrine Gibb, 1934.

-

A woman in Budapest, 1935.

-

Three models in a fashion show for hats in Paris, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

Parisian fashion shoot, 1936.

-

Berliner fashion shoot by Yva, c. 1938.

-

Writer Zora Neale Hurston, 1938.

-

A woman in Budapest, 1938.

-

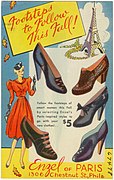

Shoe advertisement from Philadelphia, c. 1930s.

-

Calf-high lace-up boots in brown leather, c. 1925–1935.

-

Brown leather shoes with decorative plastic buckle, c. 1930–1932.

-

Silk shoes with rhinestone decoration, c. 1932.

-

Silk and leather evening shoes, c. 1933.

-

High heeled platform shoes covered in snakeskin leather, c. 1930s.

-

Silver dancing shoes, c. 1935–1940.

-

White linen summer shoes, c. 1935–1940.

-

White nubuck lace-up shoes with decorative holes, c. 1935–1940.

-

Red suede shoes with dark blue leather trims, c. 1938–1940.

-

gold-plated leather sandals, c. 1937–1940.

-

Leather sandals, c. 1938.

-

Leather evening shoes, featuring drawstrings with tassels, c. 1938–1940.

-

Black leather lace-up ankle boots, c. 1938–1940.

-

Blue-black crocodile leather shoes, c. 1939.

Hair and makeup[edit]

In the 1930s, makeup was much softer and natural than the "vampy" style of the 1920s, especially around the eyes, abadoning the dramatic, dark, kohl-rimmed eyes sported by silent movie stars.[39] Instead, a range of colours were applied over and just beyond the lid

In addition, the small rosebud-shaped lips of the 1920s gave way to the 1930s more natural lip shape, painted in a range of colors.[39] Another beauty trend of the decade was pencil-thin eyebrows, which were either heavily plucked to form a line or removed altogether and drawn on with pencil.[39]

Undergarments[edit]

In the 1930s, the bra—as recognised in modern times—was born.

https://www.anothermag.com/fashion-beauty/8054/the-brassiere-an-uplifting-history

http://gbacg.org/finery/2013/bra-support-comes-of-age-the-history-of-the-bra-1920-1930/

https://www.museumofwesternco.com/history/a-brief-history-of-womens-undergarments/

-

A corset from a 1930 catalogue, designed for those who wish to reduce the hips and flatten the abdomen.

-

Brassiere and girdle from a 1933 catalogue.

-

A corset from a 1933 catalogue.

-

A maternity support undergarment from a 1933 catalogue.

Men's fashion[edit]

General trends[edit]

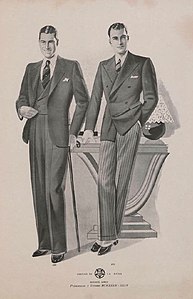

In the 1930s, Savile Row tailoring continued to dominate menswear trends.[10] Matching the shift in womenswear's silhouettes, men's suits "were worn with semi-accentuated waists", with a slimmed down silhouette that contrasted the" looser, baggy fits of the 1920s".[10] Edward VIII, then Prince of Wales, was a major fashion icon in menswear, epitomizing the English style.[40] English conservative politician Anthony Eden was also fashion leader, with his trademark look consisting of a white linen waistcoat worn with a lounge suit and his signature silk-brimmed homburg hat, which known as "the Anthony Eden".[41]

For a brief period during the decade, the tailless "mess jacket"—based on the military mess dress uniform—was worn as an alternative for the white dinner jacket during hot weather.[42]

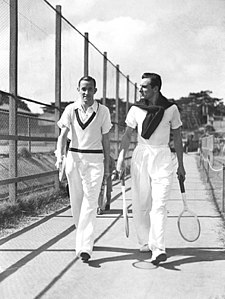

As with women, Hollywood stars played a leading role in men's fashion of the decade, especially Clark Gable, who popularized sport coats; Gary Cooper, who made two-tone shoes fashionable; and Errol Flynn.[20]

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1900-1970/

https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-decade-of-defiance-1392756874

-

A man in Hungary, 1930.

-

Lithuanian diplomats Dovas Zaunius and Vaclovas Sidzikauskas, 1932.

-

A young man in Amsterdam, 1932.

-

French athlete André Dubonnet in 1933.

-

A yougn man in Hungary, 1933.

-

Argentine fashion plate from 1934.

-

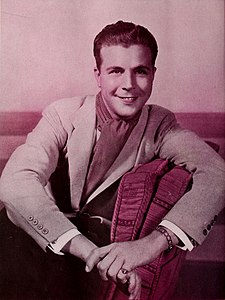

Dick Powell in Radio Stars magazine, 1934.

-

A man throwing the trash in Downtown Seattle, 1936.

-

Architects Angelo Bianchetti and Le Corbusier, 1937.

-

Norwegian politician Kjeld Stub Irgens in his garden, 1939.

Undergarments[edit]

Children's fashion[edit]

Fashion media[edit]

Illustration[edit]

-

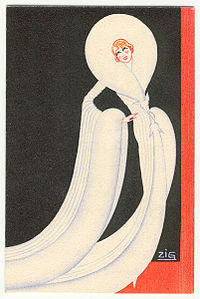

French actress Mistinguett depicted in an advertisement, c. 1930.

-

Fashion plate from the Netherlands, May 1931.

-

Fashion plate from France, November 1931.

-

Fashion plate from France, March 1932.

-

Fashion plate from France, June 1932.

-

Fashion plate from the Netherlands, March 1935.

Gallery[edit]

Women[edit]

-

1931

-

Evening coat from c. 1930, featuring cut and voided velvet, gold lamé and fox fur render.

-

Aristocrat Diana Mitford, 1932.

-

c. 1932 – Silk chiffon crepe evening gown designed by Madeleine Vionnet

-

Female workers leaving the factory in Buenos Aires, 1933.

-

A group of women at a horse race in Brisbane, 1933.

-

Woman reading a book, c. 1935.

-

A tumultuous crowd at the funeral of Carlos Gardel in Buenos Aires, 1936.

-

Portrait painting of a fashionable lady by Bernard Boutet de Monvel, 1936.

-

1938 – Champagne-colored silk evening gown with stylized silver-colored leaves.

-

George P. Putnam and Amelia Earhart in 1937.

-

A woman attending a race at the Randwick Racecourse in Sydney, 1937.

-

Zora Neale Hurston, 1938.

-

Two women in Budapest, 1939.

-

Cyclone, 1939 evening gown by Jeanne Lanvin.

Children[edit]

-

1931

-

1- Girl's dress 1931

-

6- Between 1932 and 1935

-

Girls at a Shirley Temple lookalike contest in Sydney, 1934.

-

3-1939

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thomas, Heather (July 20, 2021). "Women's Fashion History Through Newspapers: 1921-1940". Headlines and Heroes. Library of Congress. ISSN 2692-2177. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Berry (2000). p. XII

- ^ a b c d e Hennessy & Fischel, eds. (2012). p. 306

- ^ a b "The Golden Age of Glamour". The Lady. 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dirix (2021) [2011], "Introduction". In Fiell, Charlotte (ed.)

- ^ Bumpus, Jessica (March 18, 2019). "Los años treinta: la década que la moda ignoró (hasta ahora)". Vogue España (in Spanish). Condé Nast. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "Index". Design Decade 1930-1940 (Special issue of The Architectural Forum). Vol. 73, no. 4. Philadelphia: Time, Inc. October 1940. ASIN B004XU60RK.

- ^ Buchanan, Richard (1990). "Myth and Maturity: Toward a New Order in the Decade of Design". Design Issues. 6 (2). MIT Press: 70–80. Retrieved May 24, 2022 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e Andrew Yamato (February 17, 2014). Elegance in an Age of Crisis, Part 1: Hers (YouTube video). The Museum at FIT. Retrieved May 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Ramzi, Lilah (April 5, 2024). "A 1930s Fashion History Lesson: Goddess Gowns, Surrealism, and More Trends of the Escapist Era". Vogue. Retrieved May 11, 2024.

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 173–178

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 179

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 180

- ^ a b Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 182

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 184

- ^ McKelvey, Kathryn; Munslow, Janine (2007) [1997]. Illustrating Fashion. Blackwell Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 9781444313017. Retrieved May 20, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Zeegen, Lawrence; Crush (2005). The Fundamentals of Illustration. Lausanne: AVA Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 9782940373338. Retrieved May 20, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 164

- ^ "The iconic beauties who perfectly sum up 1930s style". Marie Claire. March 3, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Saulquin, Susana (2006). Historia de la moda argentina (in Spanish). Emecé Editores. pp. 100–116. ISBN 9789500427524.

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 187

- ^ a b c d e Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 165

- ^ Gundle, Stephen (2009). Glamour: A History. Oxford University Press. p. 196–198. ISBN 9780191623370. Retrieved May 20, 2022 – via Google Books.

- ^ Laver (1960). p. 240

- ^ Cumming, Valerie; Cunnington, C. W.; Cunnington, P. E. (2010). p. 8

- ^ Cumming, Valerie; Cunnington, C. W.; Cunnington, P. E. (2010). p. 11

- ^ a b c d Reddy, Karina (April 5, 2019). "1930-1939". Fashion History Timeline. History of Art Department. Fashion Institute of Technology. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 163

- ^ Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 166

- ^ a b c Hennessy & Fischel, eds. (2012). p. 291

- ^ a b c Laver (1960). p. 248

- ^ a b c d Cole & Deihl (2015). p. 183

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m ""Great Chic from Little Details" – 1930s Millinery". The Museum at FIT. April 22, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Blanco F. 2016, p. 163.

- ^ Blanco F. 2016, p. 163–164.

- ^ a b c d e Blanco F. 2016, p. 164.

- ^ Hennessy & Fischel, eds. (2012). p. 273

- ^ "Salvatore Ferragamo | Sandals". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hibbard, Ruth (August 8, 2018). "Giving face – women's make-up style and status in the 1930s". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

voguefashion historywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hennessy & Fischel, eds. (2012). p. 288

- ^ Hennessy & Fischel, eds. (2012). p. 289

Bibliography[edit]

- Berry, Sarah (2000). Screen Style: Fashion and Femininity in 1930s Hollywood. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816633128.

- Blanco F., José, ed. (2016). Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. Vol. 3. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-161-069-310-3. Retrieved May 12, 2024 – via Google Books.

- Cumming, Valerie; Cunnington, C. W.; Cunnington, P. E. (2010). The Dictionary of Fashion History. Berg Publishers. ISBN 9781847885340.

- Cole, Daniel James; Deihl, Nancy (2015). The History of Modern Fashion. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 9781780676036.

- Fiell, Charlotte, ed. (2021) [2011]. 1930s Fashion Sourcebook: The Definitive Sourcebook (eBook). Preface by Charlotte Fiell. Introduction by Emmanuelle Dirix. Welbeck Publishing. ISBN 9781802791631.

- Hennessy, Kathryn; Fischel, Anna, eds. (2012). Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. Smithsonian. DK. ISBN 9780756698355.

- Laver, James (1960). The Concise History of Costume and Fashion. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ASIN B000WONVOG.

https://books.google.com.ar/books?id=RchiAgAAQBAJ&dq=%221930s+fashion%22&hl=es&source=gbs_navlinks_s

External links[edit]

Media related to 1930s at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1930s at Wikimedia Commons