Tucson, Arizona

Tucson

| |

|---|---|

Clockwise, from the top: Downtown Tucson skyline, Old Main, University of Arizona, St. Augustine Cathedral, Pima County Courthouse | |

| Etymology: from Tohono O'odham Cuk Ṣon '(at the) base of the black hill'[1] | |

| Nicknames: "The Old Pueblo", "Optics Valley", "America's biggest small town" | |

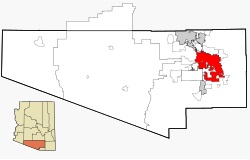

Interactive map outlining Tucson | |

Location within Pima County | |

| Coordinates: 32°13′18″N 110°55′35″W / 32.22167°N 110.92639°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Pima |

| Settled | c. 1300 A.D[2] |

| Founded | August 20, 1775 |

| Incorporated | February 7, 1877[3] |

| Founded by | Hugo O'Conor |

| Ward | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | Tucson City Council |

| • Mayor | Regina Romero (D) |

| • Vice mayor | Lane Santa Cruz |

| • City manager | Michael Ortega |

| • City council | List |

| Area | |

| • City | 241.33 sq mi (625.04 km2) |

| • Land | 241.01 sq mi (624.22 km2) |

| • Water | 0.32 sq mi (0.82 km2) |

| Elevation | 2,389 ft (728 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 542,629 |

| • Rank | 89th in North America 33rd in the United States 2nd in Arizona |

| • Density | 2,251.44/sq mi (869.29/km2) |

| • Urban | 875,441 (US: 52nd) |

| • Urban density | 2,449.8/sq mi (945.9/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,043,433 (US: 53rd) |

| Demonym(s) | Tucsonian; Tucsonan |

| Time zone | UTC-07:00 (MST (no DST)) |

| ZIP Codes | 85701-85775 |

| Area code | 520 |

| FIPS code | 04-77000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 43534[6] |

| Website | tucsonaz |

| 1 Urban = 2010 Census | |

Tucson (/ˈtuːsɒn/ TOO-son; O'odham: Cuk Ṣon)[1] is a city in and the county seat of Pima County, Arizona, United States,[7] and is home to the University of Arizona. It is the second-largest city in Arizona behind Phoenix, with a population of 542,629 in the 2020 United States census,[8] while the population of the entire Tucson metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is 1,043,433.[9] The Tucson MSA forms part of the larger Tucson-Nogales combined statistical area. Both Tucson and Phoenix anchor the Arizona Sun Corridor. The city is 108 miles (174 km) southeast of Phoenix and 60 mi (100 km) north of the United States–Mexico border.[7]

Major incorporated suburbs of Tucson include Oro Valley and Marana northwest of the city, Sahuarita[10] south of the city, and South Tucson in an enclave south of downtown. Communities in the vicinity of Tucson (some within or overlapping the city limits) include Casas Adobes, Catalina Foothills, Flowing Wells, Midvale Park, Tanque Verde, Tortolita, and Vail. Towns outside the Tucson metropolitan area include Three Points, Benson to the southeast, Catalina and Oracle to the north, and Green Valley to the south.

Tucson was founded as a military fort by the Spanish when Hugo O'Conor authorized the construction of Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón in 1775. It was included in the state of Sonora after Mexico gained independence from the Spanish Empire in 1821. The United States acquired a 29,670 square miles (76,840 km2) region of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico from Mexico under the Gadsden Purchase[11] in 1853. Tucson served as the capital of the Arizona Territory from 1867 to 1877.[12] Tucson was Arizona's largest city by population during the territorial period and early statehood, until it was surpassed by Phoenix by 1920. Nevertheless, its population growth remained strong during the late 20th century. Tucson was the first American city to be designated a "City of Gastronomy" by UNESCO in 2015.[13]

The Spanish name of the city, Tucsón (Spanish pronunciation: [tuɣˈson]), is derived from the O'odham Cuk Ṣon (Uto-Aztecan pronunciation: [tʃʊk ʂɔːn]). Cuk is a stative verb meaning "(be) black, (be) dark". Ṣon is (in this usage) a noun referring to the base or foundation of something.[1] The name is commonly translated into English as "(at the) base of the black [hill]", a reference to a basalt-covered hill now known as Sentinel Peak. Tucson is sometimes referred to as the Old Pueblo and Optics Valley, the latter referring to its optical science and telescopes known worldwide.[14][15]

History[edit]

Spanish Empire 1775–1821

First Mexican Empire 1821–1823

United Mexican States 1823–1854

United States 1854–present

The Tucson area was probably first visited by Paleo-Indians, who were known to have been in southern Arizona about 12,000 years ago. Recent archaeological excavations near the Santa Cruz River found a village site dating from 2100 BC.[16] The floodplain of the Santa Cruz River was extensively farmed during the Early Agricultural Period, c. 1200 BC to AD 150. These people hunted, gathered wild plants and nuts, and ate corn, beans, and other crops grown using irrigation canals they constructed.[16]

The Early Ceramic period occupation of Tucson had the first extensive use of pottery vessels for cooking and storage. The groups designated as the Hohokam lived in the area from AD 600 to 1450 and are known for their vast irrigation canal systems and their red-on-brown pottery.[17][18]

Italian Jesuit missionary Eusebio Francisco Kino first visited the Santa Cruz River valley in 1692. He founded the Mission San Xavier del Bac in 1700, about 7 mi (11 km) upstream from the site of the settlement of Tucson. A separate Convento settlement was founded downstream along the Santa Cruz River, near the base of what is now known as "A" mountain. Hugo Oconór (Hugo O'Conor), the founding father of the city of Tucson, Arizona, authorized the construction of a military fort in that location, Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón, on August 20, 1775 (the present downtown Pima County Courthouse was built near this site). During the Spanish period of the presidio, attacks such as the Second Battle of Tucson were repeatedly mounted by the Apache. Eventually, the town came to be called Tucsón, a Spanish version of the O'odham word for the area. It was included in the state of Sonora after Mexico gained independence from the Kingdom of Spain and its Spanish Empire in 1821.[19]

During the Mexican–American War in 1846–1848, Tucsón was captured by Philip St. George Cooke with the Mormon Battalion, but it soon returned to Mexican control as Cooke proceeded to the west, establishing Cooke's Wagon Road to California. Tucsón was not included in the Mexican Cession to the United States following the war. Cooke's road through Tucsón became one of the important routes into California during the California Gold Rush of 1849.[citation needed]

The US acquired those portions of modern-day Arizona that lay south of the Gila River by treaty from Mexico in the Gadsden Purchase on June 8, 1854. Under this treaty and purchase, Tucsón became a part of the United States of America. The American military did not formally take over control until March 1856. In time, the name of the town became standardized in English in its current form, where the stress is on the first syllable, the "u" is long, and the "c" is silent.

In 1857, Tucson was established as a stage station on the San Antonio–San Diego Mail Line. In 1858, it became third division headquarters of the Butterfield Overland Mail and operated until the line was shut down in March 1861. The Overland Mail Corporation attempted to continue running, but following the Bascom Affair, devastating Apache attacks on the stations and coaches ended operations in August 1861.[citation needed]

Tucson was incorporated in 1877, making it the oldest incorporated city in Arizona.[citation needed]

From 1877 to 1878, the area suffered a rash of stagecoach robberies. Most notable were the two holdups committed by masked road agent William Whitney Brazelton.[20] Brazelton held up two stages in the summer of 1878 near Point of Mountain Station, about 17 mi (27 km) northwest of Tucson. John Clum, of Tombstone, Arizona, fame, was one of the passengers. Pima County Sheriff Charles A. Shibell and his citizen posse killed Brazelton on August 19, 1878, in a mesquite bosque along the Santa Cruz River 3 miles (5 km) south of Tucson. Brazelton had been suspected of highway robbery in the Tucson area, the Prescott region, and the Silver City, New Mexico area. Because of the crimes and threats to his business, John J. Valentine Sr. of Wells, Fargo & Co. had sent Bob Paul, a special agent and future Pima County sheriff, to investigate.[20] The US Army established Fort Lowell, then east of Tucson, to help protect settlers and travelers from Apache attacks.

In 1882, Morgan Earp was fatally shot, in what was later referred to in the press as the "Earp–Clanton Tragedy".[21] Marietta Spence, wife of Pete Spence, one of the Cochise County Cowboys, testified at the coroner's inquest on Earp's killing and implicated Frank Stilwell in the murder. The coroner's jury concluded Pete Spence, Stilwell, Frederick Bode, and Florentino "Indian Charlie" Cruz were the prime suspects in the assassination of Morgan Earp.[22] : 250

Deputy U.S. Marshal Wyatt Earp gathered a few trusted friends and accompanied Virgil Earp and his family as they traveled to Benson to take a train to California. They found Stilwell apparently lying in wait for Virgil Earp at the Tucson station and killed Stilwell on the tracks.[23][21] After killing Stilwell, Wyatt deputized others and conducted a vendetta, killing three more cowboys over the next few days before leaving the territory.

Jim Leavy had built a reputation of having fought in at least 16 gunfights. On June 5, 1882, Leavy had an argument with faro dealer John Murphy in Tucson. The two agreed to have a duel on the Mexican border, but after hearing of Leavy's exploits as a gunfighter, Murphy decided to ambush Leavy instead. Together with two of his friends, Murphy ambushed Leavy as he was leaving the Palace Hotel, killing him. According to Wright, the three co-defendants in Leavy's murder later escaped from the Pima County Jail, but were later recaptured. Murphy and Gibson were found in Fenner, California, living under assumed names; they were retried for the murder before being found not guilty. Moyer was captured in Denver and sentenced to life in Yuma Territorial Prison, but was pardoned in 1888.[24][25]

Post-frontier life[edit]

As other settlers tried to overcome violent frontier society, in 1885, the territorial legislature founded the University of Arizona as a land-grant college on what was overgrazed ranchland between Tucson and Fort Lowell.

In 1890, Asians made up 4.2% of the city's population.[26] They were predominantly Chinese men who had been recruited as workers on the railroads.

By 1900, 7,531 people lived in Tucson. By 1910, the population increased to 13,913.[27] About this time, the U.S. Veterans Administration had begun construction of the present Veterans Hospital. The city's clean, dry air made it a destination for many veterans who had been gassed in World War I and needed respiratory therapy. In addition, these dry and high-altitude conditions were thought to be ideal for the treatment of tuberculosis, for which no cures were known before antibiotics were developed against it.[28]

The city continued to grow, with the population increasing to 20,292 in 1920[27] and 36,818 in 1940.[29] In 2006, the estimated population of Pima County, in which Tucson is located, passed one million,[30] while the City of Tucson's population was 535,000.[citation needed]

In 1912, Arizona was admitted as a state. This increased the number of flags that had been flown over Tucson to five: Spanish, Mexican, United States, Confederate, and the State of Arizona.[31]

During the territorial and early statehood periods, Tucson was Arizona's largest city and commercial center, while Phoenix was the seat of state government (beginning in 1889) and agriculture. The development of Tucson Municipal Airport increased the city's prominence. Between 1910 and 1920, though, Phoenix surpassed Tucson in population, and has continued to outpace Tucson in growth. In recent years, both Tucson and Phoenix have had some of the highest growth rates of any jurisdiction in the United States.

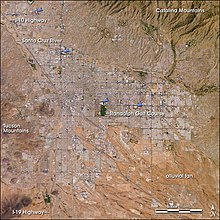

Geography[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, as of 2010, the City of Tucson has a land area of 226.71 square miles (587.2 km2). The city's elevation is 2,643 ft (806 m) above sea level (as measured at the Tucson International Airport).[32] Tucson is on an alluvial plain in the Sonoran Desert, surrounded by five minor ranges of mountains: the Santa Catalina Mountains and the Tortolita Mountains to the north, the Santa Rita Mountains to the south, the Rincon Mountains to the east, and the Tucson Mountains to the west. Tucson Mountains include 4,687 ft (1,429 m) Wasson Peak. The highest point in the area is Mount Wrightson, found in the Santa Rita Mountains at 9,453 ft (2,881 m) above sea level.

Tucson is 116 mi (187 km) southeast of Phoenix and 69 mi (111 km) north of the United States–Mexico border.[citation needed] The 2020 United States census puts the city's population at 542,629 with a metropolitan area population at 1,043,433. In 2020, Tucson ranked as the 33rd-largest city and 53rd-largest metropolitan area in the United States.[33] A major city in the Arizona Sun Corridor, Tucson is the largest city in southern Arizona, and the second-largest in the state after Phoenix. It is also the largest city in the area of the historic Gadsden Purchase. As of 2015, the Greater Tucson Metro area has exceeded a population of 1 million.

The city is built along the Santa Cruz River, formerly a perennial river. Now a dry riverbed for much of the year, it regularly floods during significant seasonal rains.

Interstate 10 runs northwest through town, connecting Tucson to Phoenix to the northwest (on the way to its western terminus in Santa Monica, California), and to Las Cruces, New Mexico and El Paso, Texas to the southeast. (Its eastern terminus is in Jacksonville, Florida).

I-19 runs south from Tucson toward Nogales and the U.S.–Mexico border. I-19 is the only Interstate highway that uses "kilometer posts" instead of "mileposts". However, speed limits are marked in miles per hour and kilometers per hour.

Neighborhoods[edit]

Downtown and Central Tucson[edit]

Similar to many other cities in the Western US, Tucson was developed by European Americans on a grid plan starting in the late 19th century, with the city center at Stone Avenue and Broadway Boulevard. While this intersection was initially near the geographic center of Tucson, the center has shifted as the city has expanded far to the east. Development to the west was effectively blocked by the Tucson Mountains. Covering a large geographic area, Tucson has many distinct neighborhoods.

Tucson's earliest neighborhoods, some of which were redeveloped and covered by the Tucson Convention Center (TCC), include:

- El Presidio,[34] Tucson's oldest neighborhood.

- Barrio Histórico,[35] also known as Barrio Libre.

- Armory Park is directly south of downtown.

- Barrio Anita,[36] named for an early settler, is located between Granada Avenue and Interstate 10.

- Barrio Tiburón, now known as the Fourth Avenue arts district, was designated in territorial times as a red-light district.

- Barrio El Jardín is named for an early recreational site, Levin's Gardens.

- Barrio El Hoyo is named for a lake that was part of the gardens. Before the convention center was built, the term El Hoyo (Spanish for 'pit' or 'hole') referred to this part of the city. Residents were mostly Mexican-American citizens and Mexican immigrants.

- Barrio Santa Rosa, dating from the 1890s, is now listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places.

Other historical neighborhoods near downtown include:

- Feldman's, just north and northwest of the University of Arizona, the neighborhood is named for Alther M. Feldman (1833–1906), an Eastern European immigrant who arrived in Tucson circa 1878. Neighborhood streets Helen and Mabel are named for his daughters.[37] Feldman owned a photographic studio known as the Arizona Tent Gallery.[38]

- Menlo Park, situated west of downtown, is adjacent to Sentinel Peak.

- Iron Horse, east of Fourth Avenue and north of the railroad tracks, is named for its proximity to the railroad, informally known by that term.

- West University is between the University of Arizona and downtown.

- Dunbar Spring is west of West University.

- Pie Allen, west and south of the university near Tucson High School, is named for John Brackett "Pie" Allen, a local entrepreneur and early mayor of Tucson.

- Sam Hughes, east of the University of Arizona, is named after a European-American pioneer in Tucson.

At the end of the 2010s, city planners and the business community worked to redevelop downtown Tucson. The primary project was Rio Nuevo, a large retail and community center that had been stalled in planning for more than a decade.[39][40] Downtown is generally regarded as the area bordered by 17th Street to the south, I-10 to the west, and 6th Street to the north, and Toole Avenue and the Union Pacific (formerly Southern Pacific) railroad tracks, site of the historic train depot[41] on the east side. Downtown is divided into the Presidio District, the Barrio Viejo, and the Congress Street Arts and Entertainment District.[42] Some authorities include the 4th Avenue shopping district, northeast of the rest of downtown and connected by an underpass beneath the UPRR tracks.

Historic attractions downtown with rich architecture include the Hotel Congress designed in 1919, the Art Deco Fox Theatre designed in 1929, the Rialto Theatre opened in 1920, and St. Augustine Cathedral completed in 1896.[43] Included on the National Register of Historic Places is the old Pima County Courthouse, designed by Roy Place in 1928.[44] The El Charro Café, Tucson's oldest restaurant, operates its main location downtown.[45]

As one of the oldest parts of town, Central Tucson is anchored by the Broadway Village shopping center, designed by local architect Josias Joesler at the intersection of Broadway Boulevard and Country Club Road. The 4th Avenue Shopping District between downtown, the university, and the Lost Barrio just east of downtown, also has many unique and popular stores. Local retail business in Central Tucson is densely concentrated along Fourth Avenue and the Main Gate Square on University Boulevard near the UA campus. The El Con Mall is also in the eastern part of midtown.

The University of Arizona, chartered in 1885, is in midtown and includes Arizona Stadium and McKale Center (named for J.F. "Pop" McKale, a prominent coach and athletics administrator at the university).[46]

The historic Tucson High School (designed by Roy Place in 1924) was featured in the 1987 film Can't Buy Me Love. The Arizona Inn (built in 1930) and the Tucson Botanical Gardens are also in Central Tucson.

Tucson's largest park, Reid Park, is in midtown and includes Reid Park Zoo and Hi Corbett Field. Speedway Boulevard, a major east–west arterial road in central Tucson, was named the "ugliest street in America" by Life in the early 1970s, quoting Tucson Mayor James Corbett.

In the late 1990s, Speedway Boulevard was awarded "Street of the Year" by Arizona Highways. Speedway Boulevard was named after an historic horse racetrack, known as the Harlem River Speedway, and more commonly called "The Speedway", in New York City. The Tucson street was called "The Speedway" from 1904 to about 1906, when "The" was removed from the title.[47]

As of the early 21st century, Central Tucson is considered bicycle-friendly. To the east of the University of Arizona, Third Street is bike-only except for local traffic; it passes by the historic homes of the Sam Hughes neighborhood. To the west, East University Boulevard leads to the Fourth Avenue Shopping District. To the North, North Mountain Avenue has a full bike-only lane for half of the 3.5 miles (5.6 km) to the Rillito River Park bike and walk multi-use path. To the south, North Highland Avenue leads to the Barraza-Aviation Parkway bicycle path.[48]

Southern Tucson[edit]

South Tucson is the name of an independent, incorporated town of 1 sq mi (2.6 km2) south of downtown. It is surrounded by the City of Tucson and was incorporated in 1936 and reincorporated in 1940.

The population is about 83% Mexican-American and 10% Native American, as residents self-identify in the census. South Tucson is widely known for its many Mexican restaurants and architectural styles. Bright murals have been painted on some walls, but city policy discourages this and many have been painted over.[49][50][51]

The south side of the city of Tucson is generally considered to be the area around 25 sq mi (65 km2) south of 22nd Street, east of I-19, west of Davis Monthan Air Force Base and southwest of Aviation Parkway, and north of Los Reales Road.[52] The Tucson International Airport and Tucson Electric Park are located here.[52]

Western Tucson[edit]

The West Side has areas of both urban and suburban development. It is generally defined as the area west of I-10. Western Tucson encompasses the banks of the Santa Cruz River and the foothills of the Tucson Mountains. Area attractions include the International Wildlife Museum and Sentinel Peak. The Marriott Starr Pass Resort and Spa serves travelers and residents.[53] As travelers pass the Tucson Mountains, they enter the area commonly referred to as "west of" Tucson or "Old West Tucson".[54] In this large, undulating plain extending south into the Altar Valley, rural residential development predominates. Attractions include Saguaro National Park West, and movie set/theme park developed at the Old Tucson Studios.

On Sentinel Peak, just west of downtown, a giant "A" was installed in honor of the University of Arizona, resulting in the nickname "A" Mountain.[55] Starting in about 1915, an annual tradition developed for freshmen to whitewash the A, which was visible for miles. After the September 11 terrorist attacks, the A was painted red, white, and blue.[56] At the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003, antiwar activists painted the A black. Competition ensued, with various sides repainting the A in different colors until the city council intervened and made the red, white, and blue colors official. In 2013, the color scheme changed back to white.[57][58] Another color may be decided by a biennial election. With the tricolor scheme, some observers complain the shape of the A is hard to distinguish from the background of the peak. Since 1993, the A has been painted green for St. Patrick's Day. It has also been given other color schemes for different causes.[58]

Northern Tucson[edit]

North Tucson includes the urban neighborhoods of Amphitheater and Flowing Wells. Usually considered the area north of Fort Lowell Road, North Tucson includes some of Tucson's primary commercial zones (Tucson Mall and the Oracle Road Corridor). Many of the city's most upscale boutiques, restaurants, and art galleries are also on the north side, including St. Philip's Plaza. The plaza is directly adjacent to the historic St. Philip's in the Hills Episcopal Church (built in 1936).

The north side also is home to the suburban community of Catalina Foothills, in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains just north of the city limits. This community includes many of the area's most expensive homes, sometimes multimillion-dollar estates. The Foothills area is generally defined as north of River Road, east of Oracle Road[59] and west of Sabino Creek. Some of the Tucson area's major resorts are in the Catalina Foothills, including Hacienda Del Sol, Westin La Paloma Resort, Loews Ventana Canyon Resort and Canyon Ranch Resort. La Encantada, an outdoor shopping mall, is also in the Foothills.

The DeGrazia Gallery of the Sun is near the intersection of Swan Road and Skyline Drive. Built by artist Ted DeGrazia starting in 1951, the 10-acre (4.0 ha) property is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and features an eclectic chapel, an art gallery, and a museum.

The expansive area northwest of the city limits is diverse, ranging from the rural communities of Catalina and parts of the town of Marana, the small suburb of Picture Rocks, the town of Oro Valley in the western foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains, and residential areas in the northeastern foothills of the Tucson Mountains. Continental Ranch (Marana), Dove Mountain (Marana), and Rancho Vistoso (Oro Valley), and Saddlebrooke (North Oro Valley) are all master planned communities in the northwest that have thousands of residents.

The community of Casas Adobes is also on the Northwest side, with the distinction of being Tucson's first suburb, established in the late 1940s. Casas Adobes is centered on the historic Casas Adobes Plaza (built in 1948). Casas Adobes is also home to Tohono Chul Park, which is now within the town of Oro Valley, (a nature preserve) near the intersection of North Oracle Road and West Ina Road. The attempted assassination of Representative Gabby Giffords, which resulted in the murders of chief judge for the U.S. District Court for Arizona, John Roll, and five other people on January 8, 2011, occurred at the La Toscana Village in Casas Adobes. The Foothills Mall is also on the northwest side in Casas Adobes.

This area is home to many of the Tucson area's golf courses and resorts, including the Preserve and Mountainview Golf Clubs at Saddlebrooke, Hilton El Conquistador Golf & Tennis Resort in Oro Valley, the Omni Tucson National Resort & Spa, and Westward Look Resort. The Ritz Carlton at Dove Mountain, the second Ritz Carlton resort in Arizona, which also includes a golf course, opened in the foothills of the Tortolita Mountains in northeast Marana in 2009.

Eastern Tucson[edit]

East Tucson is relatively new compared to other parts of the city, developed between the 1950s and the 1970s,[citation needed] with developments such as Desert Palms Park. It is generally classified as the area of the city east of Swan Road, with above-average real estate values relative to the rest of the city. The area includes urban and suburban development near the Rincon Mountains. East Tucson includes Saguaro National Park East. Tucson's "Restaurant Row" is also on the east side, along with a significant corporate and financial presence. Restaurant Row is sandwiched by three of Tucson's storied Vicinages: Harold Bell Wright Estates,[60] named after the author's ranch which occupied some of that area before the depression; the Tucson Country Club (the third to bear the name Tucson Country Club),[61] and the Dorado Country Club. Tucson's largest office building is 5151 East Broadway in east Tucson, completed in 1975. The first phases of Williams Centre, a mixed-use, master-planned development on Broadway near Craycroft Road,[62] were opened in 1987. Park Place, a recently renovated shopping center, is also along Broadway (west of Wilmot Road).

Near the intersection of Craycroft and Ft. Lowell Roads are the remnants of the Historic Fort Lowell. This area has become one of Tucson's iconic neighborhoods. In 1891, the Fort was abandoned and much of the interior was stripped of their useful components and it quickly fell into ruin. In 1900, three of the officer buildings were purchased for use as a sanitarium. The sanitarium was then sold to Harvey Adkins in 1928. The Bolsius family – Pete, Nan and Charles – purchased and renovated surviving adobe buildings of the Fort, transforming them into spectacular artistic southwestern architectural examples. Their woodwork, plaster treatment and sense of proportion drew on their Dutch heritage and New Mexican experience.

Other artists and academics throughout the middle of the 20th century, including Win Ellis, Jack Maul, Madame Germaine Cheruy and René Cheruy, Giorgio Belloli, Charles Bode, Veronica Hughart, Edward H. Spicer and Rosamond Spicer, Hazel Larson Archer and Ruth Brown, renovated adobes, built homes and lived in the area. The artist colony attracted writers and poets including beat generation Alan Harrington and Jack Kerouac whose visit is documented in his iconic book On the Road. This rural pocket in the middle of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Each year in February the vicinage celebrates its history in the City Landmark it owns and restored the San Pedro Chapel.

Situated between the Santa Catalina Mountains and the Rincon Mountains near Redington Pass northeast of the city limits is the affluent community of Tanque Verde. The Arizona National Golf Club, Forty-Niners Country Club, and the historic Tanque Verde Guest Ranch are also in northeast Tucson.

Southeast Tucson continues to experience rapid residential development. The area includes Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. The area is considered to be south of Golf Links Road. It is the home of Santa Rita High School, Chuck Ford Park (Lakeside Park), Lakeside Lake, Lincoln Park (upper and lower), The Lakecrest Vicinagess, and Pima Community College East Campus. The Atterbury Wash with its access to excellent bird watching is also in the Southeast Tucson area. The suburban community of Rita Ranch houses many of the military families from Davis-Monthan, and is near the southeasternmost expansion of the current city limits. Close by Rita Ranch and also within the city limits lies Civano,[63] a planned development meant to showcase ecologically sound building practices and lifestyles.

Climate[edit]

Tucson has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh), with two major seasons, a hot summer and mild winter. Tucson averages 10.61 inches (269.5 mm) of precipitation per year, concentrated during the Pacific storms of winter and the North American Monsoon of summer. Fall and spring tend to be sunny and dry.[64] Despite being at a more southerly latitude than Phoenix, Tucson is slightly cooler and wetter due to a variety of factors, including elevation and orographic lift in surrounding mountains, though Tucson does occasionally see warmer daytime temperatures in the winter.[65]

Summer is characterized by average daily high temperatures between 98 and 102 °F (37 and 39 °C) and low temperatures between 71 and 77 °F (22 and 25 °C). Early summer is characterized by low humidity and clear skies; mid- and late summer are characterized by higher humidity, cloudy skies, and frequent rain. The sun is intense in Tucson during part of the year, and those who spend time outdoors need protection. Recent studies show that the rate of skin cancer in Arizona is at least three times higher than in more northerly regions. Additionally, heat stroke is a concern for hikers, mountain bikers, and adventurers who explore canyons, open desert lands, and other exposed areas.[66]

While monsoon season officially begins on June 15, the arrival of the North American Monsoon is unpredictable, as it varies from year to year. On average, Tucson receives its first monsoon storms around July 3. Monsoon activity generally persists through August and often into September.[67] During the monsoon, the humidity is much higher than the rest of the year. It begins with clouds building up from the south in the early afternoon, followed by intense thunderstorms and rainfall, which can cause flash floods. The evening sky at this time of year is often pierced with dramatic lightning strikes. Large areas of the city do not have storm sewers, so monsoon rains flood the main thoroughfares, usually for no longer than a few hours. A few underpasses in Tucson have "feet of water" scales painted on their supports to discourage fording by automobiles during a rainstorm.[68] Arizona traffic code Title 28–910, the so-called "Stupid Motorist Law", was instituted in 1995 to discourage people from entering flooded roadways. If the road is flooded and a barricade is in place, motorists who drive around the barricade can be charged up to $2000 for costs involved in rescuing them.[69] Despite the warnings and precautions, three Tucson drivers have drowned between 2004 and 2010.[citation needed]

The weather in the fall is much like spring, dry, with warm/cool nights and warm/hot days. Temperatures above 100 °F (38 °C) are possible into early October. Temperatures decline at the quickest rate in October and November, and are normally the coolest in late December and early January.

Winters in Tucson are mild relative to other parts of the United States. Average daytime highs range between 65 and 70 °F (18 and 21 °C), with overnight lows between 40 and 44 °F (4 and 7 °C). Tucson typically averages three hard freezes per winter season, with temperatures dipping to the mid- or low 20s (−7 to −4 °C), but this is typically limited to only a very few nights. Although rare, snow occasionally falls in lower elevations in Tucson and is common in the Santa Catalina Mountains. The most recent snowfall was on March 2, 2023, when a winter storm caused snow to fall throughout most of the southwest. Tucson airport recorded 1.0 in (2.5 cm) of snow, the seventh heaviest March snowfall on record.[70]

Early spring is characterized by gradually rising temperatures and several weeks of vivid wildflower blooms beginning in late February and into March. During this time of year the diurnal temperature variation normally attains its maximum, often surpassing 30 °F (17 °C).

Since records began in 1894, the record maximum temperature was 117 °F (47 °C) on June 27, 1990, and the record minimum temperature was 6 °F (−14 °C) on January 7, 1913. There are an average of 158 days annually with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and an average of 12 days with lows reaching or below the freezing mark. Average annual precipitation is 10.61 in (269 mm). On average, 47.4 days have measurable precipitation. The wettest year was 1905, with 24.17 in (614 mm) and the driest year was 2020 with 4.16 in (106 mm). The most precipitation in one month was 8.06 in (205 mm) in July 2021. The most precipitation in 24 hours was 3.93 in (100 mm) on July 29, 1958. Annual snowfall averages 0.1 in (0.25 cm). The most snow in one winter was 6.8 in (17 cm) in winter 1971–1972. The most snow in one month was 6.8 in (17 cm) in December 1971.

| Climate data for Tucson, Arizona (Tucson Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1894−present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

92 (33) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

111 (44) |

117 (47) |

114 (46) |

112 (44) |

111 (44) |

103 (39) |

94 (34) |

85 (29) |

117 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 79.1 (26.2) |

82.5 (28.1) |

88.7 (31.5) |

95.4 (35.2) |

102.8 (39.3) |

109.2 (42.9) |

109.0 (42.8) |

107.0 (41.7) |

103.5 (39.7) |

97.9 (36.6) |

87.6 (30.9) |

78.9 (26.1) |

110.7 (43.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 66.5 (19.2) |

69.2 (20.7) |

75.8 (24.3) |

82.9 (28.3) |

91.8 (33.2) |

101.2 (38.4) |

100.2 (37.9) |

98.6 (37.0) |

95.1 (35.1) |

86.3 (30.2) |

75.1 (23.9) |

65.5 (18.6) |

84.0 (28.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.6 (12.0) |

56.2 (13.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

68.1 (20.1) |

76.8 (24.9) |

86.1 (30.1) |

88.2 (31.2) |

86.9 (30.5) |

82.8 (28.2) |

72.6 (22.6) |

61.5 (16.4) |

53.0 (11.7) |

70.6 (21.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 40.8 (4.9) |

43.2 (6.2) |

48.0 (8.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

71.1 (21.7) |

76.3 (24.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

70.4 (21.3) |

59.0 (15.0) |

47.9 (8.8) |

40.5 (4.7) |

57.3 (14.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 28.5 (−1.9) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

35.6 (2.0) |

41.1 (5.1) |

50.3 (10.2) |

60.3 (15.7) |

67.8 (19.9) |

68.3 (20.2) |

60.8 (16.0) |

44.9 (7.2) |

32.9 (0.5) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 6 (−14) |

17 (−8) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

32 (0) |

43 (6) |

49 (9) |

55 (13) |

43 (6) |

26 (−3) |

19 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

6 (−14) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.84 (21) |

0.84 (21) |

0.56 (14) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.23 (5.8) |

2.21 (56) |

1.98 (50) |

1.32 (34) |

0.67 (17) |

0.56 (14) |

0.96 (24) |

10.61 (269) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 8.8 | 8.5 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 47.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 48.4 | 42.7 | 37.0 | 27.0 | 22.0 | 21.1 | 41.6 | 46.6 | 41.7 | 38.4 | 42.7 | 50.0 | 38.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 28.2 (−2.1) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

36.3 (2.4) |

55.8 (13.2) |

58.1 (14.5) |

51.1 (10.6) |

39.2 (4.0) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

36.8 (2.7) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 259.9 | 258.2 | 320.7 | 357.2 | 400.8 | 396.9 | 342.7 | 335.6 | 316.4 | 307.4 | 264.4 | 245.8 | 3,806 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 81 | 84 | 86 | 92 | 94 | 93 | 79 | 81 | 85 | 87 | 84 | 79 | 86 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew points and sun 1961–1990)[71][72][73] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 400 | — | |

| 1860 | 915 | 128.8% | |

| 1870 | 3,215 | 251.4% | |

| 1880 | 7,007 | 117.9% | |

| 1890 | 5,150 | −26.5% | |

| 1900 | 7,531 | 46.2% | |

| 1910 | 13,193 | 75.2% | |

| 1920 | 20,292 | 53.8% | |

| 1930 | 32,506 | 60.2% | |

| 1940 | 35,752 | 10.0% | |

| 1950 | 45,454 | 27.1% | |

| 1960 | 212,892 | 368.4% | |

| 1970 | 262,933 | 23.5% | |

| 1980 | 330,537 | 25.7% | |

| 1990 | 405,371 | 22.6% | |

| 2000 | 486,699 | 20.1% | |

| 2010 | 520,116 | 6.9% | |

| 2020 | 542,629 | 4.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[74] 2010–2020[75] | |||

According to 2020 census, the racial composition of Tucson was:

- Non-Hispanic white: 43.6%

- African American: 5.6%

- Native American: 2.9%

- Asian American: 3.2%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.3%

- Hispanic or Latino: 42.2%

According to the 2010 American Census Bureau, the racial composition of Tucson was:

- Non-Hispanic White: 47.2%

- Black or African American: 5.0%

- Native American: 2.7%

- Asian: 2.9%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.2%

- Other race: 17.8%

- Two or more races: 3.4%

- Hispanic or Latino: 41.6%; Mexican Americans made up 36.1% of the city's population.

As of the census of 2010, 520,116 people, 229,762 households, and 112,455 families resided in the city. The population density was 2,500.1 inhabitants per square mile (965.3 inhabitants/km2). The 209,609 dwelling units had an average density of 1,076.7 per square mile (415.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 69.7% White (down from 94.8% in 1970[77]), 5.0% Black or African-American, 2.7% Native American, 2.9% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 16.9% from other races, and 3.8% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 41.6% of the population.[78] Non-Hispanic Whites were 47.2% of the population in 2010,[78] down from 72.8% in 1970.[77]

According to research by demographer William H. Frey using data from the 2010 United States census, Tucson has the lowest level of Black-White segregation of any of the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States.[79]

Of the 192,891 households, 29.0% had children under 18 living with them, 39.7% were married couples living together, 13.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.7% were not families. About 32.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.3% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.42, and the average family size was 3.12.

In the inner city, the population has 24.6% under 18, 13.8% from 18 to 24, 30.5% from 25 to 44, 19.2% from 45 to 64, and 11.9% who were 65 or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.0 males. For every 100 females 18 and over, there were 93.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,981, and for a family was $37,344. Males had a median income of $28,548 versus $23,086 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,322. About 13.7% of families and 18.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.6% of those under 18 and 11.0% of those 65 or over.[80]

Economy[edit]

Much of Tucson's economic development has centered on the development of the University of Arizona, which is the city's largest employer. Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, on the city's southeastern edge, also provides many jobs for Tucson residents. Its presence, as well as the presence of the US Army Intelligence Center (Fort Huachuca, the region's largest employer, in nearby Sierra Vista), has led to the development of many high-technology industries, including government contractors. The city of Tucson is also a major hub for the Union Pacific Railroad's Sunset Route that links the Los Angeles ports with the South/Southeast regions of the country.

Raytheon Missiles and Defense (formerly Hughes Aircraft Co.),[81] Texas Instruments, IBM, Intuit Inc., Universal Avionics, Honeywell Aerospace, Sunquest Information Systems, Sanofi-Aventis, Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., and Bombardier Aerospace all have a large presence in Tucson. Roughly 150 Tucson companies are involved in the design and manufacture of optics and optoelectronics systems, earning Tucson the nickname "Optics Valley".[82] Much of this comes from the Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona, which is one of few locations in the world that can cast the enormous mirrors used in telescopes around the world and in space.

Tourism is another major industry in Tucson. The city's many resorts, hotels, and attractions bring in $2 billion and over 3.5 million visitors annually.[83]

One of the major annual attractions is the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, and its associated shows, all held generally in the first two weeks of February. These associated shows (such as gems, jewelry, beads, and fossils) are held throughout the city, with 43 different shows in 2010. This makes Tucson's the largest such exposition in the world. Its yearly economic impact in 2015 was evaluated at $120 million.[84]

In addition to vacationers, many winter residents, or "snowbirds", are attracted to Tucson's mild winters and live here on a seasonal basis. They also contribute to the local economy. Snowbirds often purchase second homes in Tucson and nearby areas, contributing significantly to the property tax base.

Top employers[edit]

According to Tucson's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[85] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | University of Arizona | 11,251 |

| 2 | Raytheon Technologies | 9,600 |

| 3 | State of Arizona | 8,580 |

| 4 | Davis–Monthan Air Force Base | 8,406 |

| 5 | Pima County | 7,060 |

| 6 | Tucson Unified School District | 6,770 |

| 7 | Banner University Medical Center Tucson | 6,272 |

| 8 | U.S. Customs and Border Protection | 5,739 |

| 9 | Freeport-McMoran Copper & Gold, Inc. | 5,530 |

| 10 | Walmart | 5,500 |

Arts and culture[edit]

Annual cultural events and fairs[edit]

Tucson Gem and Mineral Show[edit]

The Tucson Gem & Mineral Show is one of the largest gem and mineral shows in the world and has been held for over 50 years. The show is only one part of the gem, mineral, fossil and bead gathering held across more than 45 different sites in Tucson.[86] The shows run from late January to mid-February, with the official show lasting two weeks in February.

Tucson Festival of Books[edit]

Since 2009, the Tucson Festival of Books has been held annually over a two-day period in March at the University of Arizona. By 2010 it had become the fourth largest book festival in the United States, with 450 authors and 80,000 attendees.[87] In addition to readings and lectures, it features a science fair, varied entertainment, food, and exhibitors ranging from local retailers and publishers to regional and national nonprofit organizations.[88]

Tucson Folk Festival[edit]

For the past 33 years, the Tucson Folk Festival has taken place the first Saturday and Sunday of May in downtown Tucson's El Presidio Park. In addition to nationally known headline acts each evening, the Festival highlights over 100 local and regional musicians on five stages and is one of the largest free festivals in the country. All stages are within easy walking distance. Organized by the Tucson Kitchen Musicians' Association,[89] volunteers make this festival possible. KXCI 91.3-FM, Arizona's only community radio station, is a major partner, broadcasting from the Plaza Stage throughout the weekend. There are also many workshops, events for children, sing-alongs, and a popular singer-songwriter contest. Musicians typically play 30-minute sets, supported by professional audio staff volunteers. A variety of food and crafts are available at the festival, as well as local microbrews. All proceeds help fund future festivals.

Fourth Avenue Street Fair[edit]

There are two Fourth Avenue Street Fairs, in December and late March/early April, staged between 9th Street and University Boulevard, that feature arts and crafts booths, food vendors and street performers. The fairs began in 1970 when Fourth Avenue, which at the time had half a dozen thrift shops, several New Age bookshops and the Food Conspiracy Co-Op, was a gathering place for hippies, and a few merchants put tables in front of their stores to attract customers before the holidays.

These days, the street fair has grown into a large corporate event, with most tables owned by outside merchants. It hosts mostly traveling craftsmen selling various arts such as pottery, paintings, wood working, metal decorations, candles, and many others.

Tucson Rodeo (Fiesta de los Vaqueros)[edit]

Another popular event held in February, which is early spring in Tucson, is the Fiesta de los Vaqueros, or rodeo week, founded by winter visitor, Leighton Kramer.[90] While at its heart the Fiesta is a sporting event, it includes what is billed as "the world's largest non-mechanized parade".[91] The Rodeo Parade is a popular event as most schools give two rodeo days off instead of Presidents' Day. The exception is Presidio High (a non-public charter school), which does not get either. Western wear is seen throughout the city as corporate dress codes are cast aside during the Fiesta. The Fiesta de los Vaqueros marks the beginning of the rodeo season in the United States.[citation needed]

Tucson Meet Yourself[edit]

Every October for the past 30 years, the Tucson Meet Yourself festival[92] has celebrated the city's many ethnic groups. For one weekend, the downtown area features dancing, singing, artwork, and food from more than 30 different ethnicities. The event is held at and around the Jacome Plaza,[93] located in front of the Joel D. Valdez Main Library. All performers are from Tucson and the surrounding area, in keeping with the idea of "meeting yourself." The records of the Tucson Meet Yourself Festival reside at the University of Arizona Special Collections Library.[94]

Tucson Modernism Week[edit]

Since 2012, during the first two weekends of October, the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation hosts Tucson Modernism Week.[95] The event includes more than 30 programs including tours, lectures, exhibits, films and parties. The events are in mid-century modern buildings and neighborhoods throughout the city and highlight the work of significant architects and designers who contributed to the development and history of southern Arizona including: architect Arthur Brown, fashion designer Dolores Gonzales, architect Bob Swaim, architect Anne Rysdale, textile designers Harwood and Sophie Steiger, architect Nick Sakellar, architectural designer Tom Gist, furniture designer Max Gottschalk, architect Ned Nelson, landscape architect Guy Green, architect Juan Worner Baz, and many others.

All Souls Procession Weekend[edit]

The All Souls Procession, held in early November, is one of Tucson's largest festivals. Modeled on the Mexican holiday Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), it combines aspects of many different cultural traditions.[96] The first All Souls Procession was organized by local artist Susan Kay Johnson in 1990 and involved 35 participants; by 2013, participation was estimated at 50,000.[97][98]

The Procession, held at sundown, consists of a non-motorized parade through downtown Tucson featuring many floats, sculptures, and memorials, in which the community is encouraged to participate. The parade is followed by performances on an outdoor stage, culminating in the burning of an urn in which written prayers have been collected from participants and spectators.[98][99] The event is organized and funded by the non-profit arts organization Many Mouths One Stomach, with the help of volunteers and donations from the public and local businesses.[98]

Cyclovia Tucson[edit]

Cyclovia Tucson is an annual event supported by Living Streets Alliance that invites people of all ages and abilities to walk, bike, and roll down car-free streets for a day. Cyclovia is an Open Streets initiative designed to maximize the enormous amount of space taken up by roads in sprawling cities like Tucson. Since 2012, Cyclovia transforms the streets of metro Tucson into a block party atmosphere to socialize, incorporating partnerships with small businesses, and giving people the opportunity to move freely through the streets without moving cars. Cyclovia happens twice a year, typically in the spring and in the fall.

Cultural and other attractions[edit]

Cultural and other attractions include:

- Arizona Historical Society

- The Fremont House is an original adobe house in the Tucson Community Center that was saved when one of Tucson's earliest barrios was razed as part of urban renewal.

- Fort Lowell Museum

- Mission San Xavier del Bac

- Old Tucson Studios, built as a set for the movie Arizona, is a movie studio and theme park for classic Westerns.

- The Tucson Museum of Art was established as part of an art school, the Art Center, which was founded by local Tucson artists, including Rose Cabat.[100]

- The University of Arizona Museum of Art includes works by Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko as part of the Edward J. Gallagher Memorial Collection, a tribute to a young man who was killed in a boating accident. The museum also includes the Samuel H. Kress Collection of European works from the 14th to 19th centuries and the C. Leonard Pfeiffer Collection of American paintings.

- Center for Creative Photography, a leading museum with many works by major artists such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston.

- International Wildlife Museum maintains an exhibition of over four-hundred different mounted and prepared animal species hunted from around the globe.[101][102]

- The DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun is an iconic Tucson landmark in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains.[citation needed]

- Titan Missile Museum is about 25 mi (40 km) south of the city on I-19. This is a Cold War-era Titan nuclear missile silo (billed as the only remaining intact post-Cold War Titan missile silo) turned tourist stop.

- Pima Air & Space Museum has a wide assortment of aircraft on display both indoors and outdoors.

- Pima County Fair

- Trail Dust Town is an outdoor shopping mall and restaurant complex built from the remains of a 1950 western movie set.

- Museum of the Horse Soldier

- Jewish History Museum

- Centennial Hall opened in 1937 as the University of Arizona's campus auditorium, designed by architect Roy Place.

- Tucson Chinese Cultural Center

- Tucson Loop Shared Use Bike Path

- Arizona State Museum (on the University of Arizona campus)

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Tucson

Fourth Avenue, near the University of Arizona, is home to many shops, restaurants, and bars, and hosts the annual 4th Avenue Street Fair every December and March. University Boulevard, leading directly to the UA Main Gate, is also the center of numerous bars, retail shops, and restaurants most commonly frequented by the large student population of the UA.

El Tiradito is a religious shrine in the downtown area. The shrine dates back to the early days of Tucson. It is based on a love story of revenge and murder. People stop by the shrine to light a candle for someone in need, a place for people to go give hope.

Biosphere 2 is a 3.14-acre (1.27 ha) educational facility designed to mimic a tropical or sub-tropical climate-controlled environment.[103]

Literary arts[edit]

The accomplished and awarded writers (poets, novelists, dramatists, nonfiction writers) who have lived in Tucson include Edward Abbey, Erskine Caldwell, Barbara Kingsolver and David Foster Wallace. Some were associated with the University of Arizona, but many were independent writers who chose to make Tucson their home. The city is particularly active in publishing and presenting contemporary innovative poetry in various ways. Examples are the Chax Press, a publisher of poetry books in trade and book arts editions, and the University of Arizona Poetry Center, which has a sizable poetry library and presents readings, conferences, and workshops.

Performing arts[edit]

Theater groups include the Arizona Theatre Company, which performs in the Temple of Music and Art, and Arizona Onstage Productions, a not-for-profit theater company devoted to musical theater. Broadway in Tucson presents the touring reproductions of many Broadway-style events. The Gaslight Theater produces musical melodrama parodies in the old Jerry Lewis Theater and has been in Tucson since 1977.[104]

Tucson is home to the Tucson Symphony Orchestra, the oldest performing arts organization in the state of Arizona.

The annual Tucson Fringe Festival, held in various local venues in and around Downtown Tucson, offers non-traditional artistic performances at low cost to the public. The festival is held in early January each year.

City of Tucson Designated Historic Landmarks[edit]

- San Pedro Chapel, Designated 1981

- Smith House, Designated 1986

- Cannon-Douglas House, Designated 1986

- Sosa–Carrillo–Fremont House, Part of TCC PAD, Designated 1987

- El Con Water Tower, Designated 1991

- El Tiradito Wishing Shrine, Designated 1995

- Valley of the Moon, Designated, 2015

- Broadway Village, Designated 2015

- Voorhees-Pattison House, Designated 2015

- Rubinstein House, Designated 2018

- Williamson House, Designated 2018

- Hirsh's Shoes, Designated 2018

- Benedictine Monastery, Designated 2019

- Ball-Paylore House, Designated 2020

- Kirby Lockard House, Designated 2020

- Beck House, Designated 2021

- Loerpabel Joesler House, Designated 2022

Music[edit]

Musical organizations include the Tucson Symphony Orchestra (founded in 1929) and Arizona Opera (founded as the Tucson Opera Company in 1971). The Tucson Arizona Boys Chorus, founded in 1939 and performing a wide-ranging repertoire that incorporates rope tricks, has represented the city as "Ambassadors in Levi's" at local, national, and international concerts.[105][106] The Tucson Girls Chorus runs six choirs and numerous satellite choirs which perform locally, nationally, and internationally.[107]

Tucson is considered an influential center for Mariachi music and is home to a large number of Mariachi musicians and singers.[108] The Tucson International Mariachi Conference, hosted annually since 1982, involves several hundred mariachi bands and folklorica dance troops during a three-day festival in April.[109] The Norteño Festival and Street Fair in the enclave city of South Tucson is held annually at the end of summer.

Tucson is also known nationally for its punk scene. Since the late 1970s punk subculture has flourished in Tucson.[110] At present there are multiple punk bars downtown and house venues in the surrounding neighborhoods.[111]

Prominent musicians based in Tucson or with ties to the city include Linda Ronstadt, Lalo Guerrero, The Dusty Chaps, Howe Gelb, Bob Log III, Calexico, Giant Sand, Hipster Daddy-O and the Handgrenades, The Bled, AJJ, Ramshackle Glory, and Tucson's official troubadour Ted Ramirez. The Tucson Area Music Awards, or TAMMIES, are an annual event.[112]

Television and film[edit]

Tucson has been the setting and filming location for multiple films. Some notable films that have been filmed in Tucson include Revenge of the Nerds, Can't Buy Me Love, Major League, Tombstone, and Tin Cup.[113] The city is also a common filming location and setting for Western films, most were filmed at Old Tucson.[114] The television show Hey Dude was filmed at Tanque Verde Ranch.[115] Additionally, the fictional motorcycle clubs the Sons of Anarchy and Mayans from the television shows Sons of Anarchy and Mayans M.C. both have Tucson chapters that are featured in the show. In the season 4 Sons of Anarchy episode "Una Venta", the cast travels to Tucson to discuss an issue with the Tucson chapter.[116] The upcoming TV series Duster began filming in Tucson in October 2021. The series is specifically being filmed in downtown Tucson and the Tucson Mountains region of Saguaro National Park.[117][118]

Cuisine[edit]

Tucson is well known for its Sonoran-style Mexican food.[119][120] Since the turn of the century, other ethnic restaurants and fine dining choices have proliferated.[121][122]

In 2015 the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) designated Tucson a "world city of gastronomy" under the Creative Cities Network program,[123] becoming thus the first city of gastronomy in the United States.[124][125] The city's focus on food includes Mission Garden, a living agricultural museum that showcases the crops and trees that have been grown in the area for over 4000 years.

The Sonoran hot dog is very popular in Tucson. A hot dog is wrapped in bacon and grilled, served on a bolillo-style hot dog bun, and topped with pinto beans, onions, tomatoes, and a variety of additional condiments, often including mayonnaise, mustard, and jalapeño salsa.[126][127][128] Tucson also has a strong, though contested, claim to being the place of origin of the chimichanga.

Nicknames[edit]

Tucson is commonly known as "The Old Pueblo". While the exact origin of this nickname is uncertain, it is commonly traced back to Mayor R. N. "Bob" Leatherwood. When rail service was established to the city on March 20, 1880, Leatherwood celebrated the fact by sending telegrams to various leaders, including the President of the United States and the Pope, announcing the "ancient and honorable pueblo" of Tucson was now connected by rail to the outside world. The term became popular with newspaper writers who often abbreviated it as "A. and H. Pueblo". This in turn transformed into the current form of "The Old Pueblo".[129]

In the early 1980s, city leaders ran a contest searching for a new nickname. The winning entry was the "Sunshine Factory".[130] The new nickname never gained popular acceptance, allowing the old name to remain in common use.[131] Tucson was dubbed "Optics Valley" in 1992 when Business Week ran a cover story on the Arizona Optics Industry Association.[132]

Sports[edit]

Tucson is not represented in any of the five major sports leagues of the United States: the NFL, MLB, the NBA, the NHL, or MLS.

The University of Arizona's athletic teams, most notably the men's basketball, football, baseball, and softball teams, have strong local interest. The men's basketball team, formerly coached by Hall of Fame head coach Lute Olson and currently coached by Tommy Lloyd, made 25 straight NCAA Tournaments appearances (1985–2009) and won the 1997 National Championship. Arizona's softball team has reached the NCAA National Championship game 12 times and has won 8 times, most recently in 2007. Arizona's baseball team won NCAA National Championships in 1976, 1980, 1986, and 2012. The university's swim teams have gained international recognition, with swimmers coming from as far as Japan and Africa to train with coach Frank Busch, who has also worked with the U.S. Olympic swim team for numerous years. Both men's and women's swim teams won the 2008 NCAA National Championships.[133]

In ice hockey, the Tucson Roadrunners of the American Hockey League began play during the 2016–2017 season after relocating to Tucson in 2016. They play at the Tucson Convention Center Arena from October to April, and are the top affiliate of the Arizona Coyotes.

In American football, the Indoor Football League announced in 2018 they were bringing an expansion team to Tucson to play at the Tucson Convention Center's newly renovated Tucson Arena starting in 2019. That team would be announced as the Tucson Sugar Skulls.[134]

In baseball, the Tucson Saguaros of the independent Pecos League began play in 2016 and play at the Kino Veterans Memorial Stadium. They won the league in their inaugural season and won two more championships in 2020 and 2021. The Tucson Padres played at Kino Veterans Memorial Stadium from 2011 to 2013. They served as the AAA affiliate of the San Diego Padres. The team, formerly known as the Portland Beavers, temporarily moved to Tucson from Portland while the team awaited a new stadium in Escondido.[135][136] Legal issues derailed the plans to build the Escondido stadium, so they moved to El Paso, Texas for the 2014 season and onward. Previously, the Tucson Sidewinders, a triple-A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks from 1998 to 2008, won the Pacific Coast League championship and unofficial AAA championship in 2006. The Sidewinders played at Tucson Electric Park (now called Kino Sports Complex) and were in the Pacific Conference South of the PCL. The Sidewinders were sold in 2007 and moved to Reno, Nevada after the 2008 season. They now compete as the Reno Aces, who have served as a triple-A affiliate for the Arizona Diamondbacks since 2009.

In soccer, Tucson is host to the Mobile Mini Sun Cup, the largest pre-season Major League Soccer (MLS) tournament in the country. As many as 11 MLS soccer clubs train in Tucson every winter. Tucson is also host to FC Tucson, a professional soccer club that plays at the Kino Sports Complex North Stadium in the third-tier USL League Two.

The United States Handball Association Hall of Fame is in Tucson.[137]

Tracks include Tucson Raceway Park and Rillito Downs. Tucson Raceway Park hosts NASCAR-sanctioned auto racing events and is one of only two asphalt short tracks in Arizona. Rillito Downs is an in-town destination on weekends in January and February each year. This historic track held the first organized quarter horse races in the world, and they are still racing there. The racetrack is threatened by development. The Moltacqua racetrack, was another historic horse racetrack on what is now Sabino Canyon Road and Vactor Ranch Trail, but it no longer exists.[138]

Parks and recreation[edit]

The city has more than 120 parks, from small and local to larger parks with ballfields, natural areas, lakes, 5 public golf courses, and Reid Park Zoo. "The Loop" is a popular system of walking/running/bicycling/horseback trails encircling the city primarily along washes, and it is usually well separated from traffic. Several scenic parks and points of interest are also nearby, including the Tucson Botanical Gardens, Tohono Chul Park, Saguaro National Park, Sabino Canyon, and Biosphere 2 (just north of the city, near the town of Oracle).

Tumamoc Hill is an active research site maintained by the University of Arizona and Pima County that doubles as a popular walking/running trail. The paved trail on Tumamoc Hill is 1.5 miles uphill (3 miles full trip), divided into two parts. The lower half is a much more gradual slope compared to the steep upper half reaching a final elevation of 2,340 ft where it overlooks most of the city of Tucson. The trail attracts around 1500 visits a day from various demographics of the Tucson area.[139]

Mt. Lemmon is 25 miles (40 km) north (by the Catalina Highway) and over 6,700 feet (2,000 m) above Tucson in the Santa Catalina Mountains in the Coronado National Forest[140]. Outdoor activities in the Catalinas include hiking, mountain biking, birding, rock climbing, picnicking, camping, swimming in mountain stream pools, sky rides at Ski Valley, fishing, and photography. In winter with enough snow, the sky ride converts back to skiing at the southernmost ski resort in the continental United States. Summerhaven, a community near the top of Mt. Lemmon, is also a popular destination.

The League of American Bicyclists gave Tucson a gold rating for bicycle friendliness in late April 2007. Tucson hosts the largest perimeter cycling event in the United States. The ride, called "El Tour de Tucson", takes place each November on the Saturday before Thanksgiving. El Tour de Tucson produced and promoted by Perimeter Bicycling has had as many as 10,000 participants from all over the world. In 2019, ridership is expected to be 6,000 cyclists.[141] Tucson is one of only nine cities in the U.S. to receive a gold rating or higher for cycling friendliness from the League of American Bicyclists. The city is known for its winter cycling opportunities, with teams and riders from around the world spending a portion of the year training in Tucson's year-round biking climate. Popular mountain biking areas include Tucson Mountain Park, Sweetwater Preserve, the Tortolita Mountain trail systems, and Fantasy Island. Road cyclists take on Catalina Highway's steep climb year-round.

Government[edit]

Pima County supported John Kerry 53% to 47% in the 2004 U.S. Presidential Election,[142] and Barack Obama 54% to 46% in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election.[143] In the latter year, Pima was the only county to vote against Arizona's gay marriage ban.[144] In 2013, Tucson became the second city in Arizona to approve of civil unions for same-sex partners.[145] The city was the first in the state to pass a domestic partnership registry earlier in 2003.[146]

In general, Tucson and Pima County support the Democratic Party, while the state's largest metropolitan area, greater Phoenix, has traditionally supported the Republican Party. Congressional redistricting in 2013, following the publication of the 2010 Census, divided the Tucson area into three Federal Congressional districts (the first, second and third of Arizona). The city center is in the 3rd District, represented by Raul Grijalva, a Democrat, since 2003, while the more affluent residential areas to the south and east are in the 2nd District, represented by Democrat Ann Kirkpatrick since 2019, and the exurbs north and west between Tucson and Phoenix in the 1st District are represented by Democrat Tom O'Halleran since 2016.[147] The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Tucson. The Tucson Main Post Office is at 1501 South Cherrybell Stravenue.[148]

City government[edit]

Tucson follows the "weak mayor" model of the council-manager form of local government. The six-member city council holds exclusive legislative authority, and shares executive authority with the mayor, who is elected by the voters independently of the council. An appointed city manager is responsible for the day-to-day operations of the city. Tucson is the only city in Arizona that holds officially partisan elections for city offices, with candidates nominated through party primaries.[149]

Both the council members and the mayor serve four-year terms; none face term limits. Council members are nominated by their wards via a ward-level primary held in August. The top vote-earners from each party then compete at-large for their ward's seat on the November ballot. In other words, on election day the whole city votes on all the council races up for that year. Council elections are severed: Wards 1, 2, and 4 (as well as the mayor) are up for election in the same year (most recently 2015), while Wards 3, 5, and 6 share another year (most recently 2017).

Tucson is known for being a trailblazer in voluntary partial publicly financed campaigns. Since 1985, both mayoral and council candidates have been eligible to receive matching public funds from the city. To become eligible, council candidates must receive 200 donations of $10 or more (300 for a mayoral candidate). Candidates must then agree to spending limits equal to 33¢ for every registered Tucson voter, or $79,222 in 2005 (the corresponding figures for mayor are 64¢ per registered voter, or $142,271 in 2003). In return, candidates receive matching funds from the city at a 1:1 ratio of public money to private donations. The only other limitation is that candidates may not exceed 75% of the limit by the date of the primary. Many cities, such as San Francisco and New York City, have copied this system, albeit with more complex spending and matching formulas.

Mayor Regina Romero (D) was sworn into office on December 2, 2019, succeeding Jonathan Rothschild (D) who was sworn into office on December 5, 2011, succeeding Robert E. Walkup (R), who took office in 1999.[150] Walkup was preceded by George Miller (D), 1991–1999; Tom Volgy (D), 1987–1991; Lew Murphy (R), 1971–1987; and Jim Corbett (D), 1967–1971.

| Tucson City Council Members | Ward | First Elected | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lane Santa Cruz | 1 | 2019 | [151] |

| Paul Cunningham | 2 | 2010 (Appointed) | [152] |

| Karin Uhlich | 3 | 2021[153] | [154] |

| Nikki Lee | 4 | 2019 | [155] |

| Richard Fimbres | 5 | 2009 | [156] |

| Steve Kozachick | 6 | 2009[157] | [158] |

Education[edit]

Post-secondary education[edit]

- University of Arizona: established in 1885; the second largest university in the state in terms of enrollment with over 36,000 students.

- Pima Community College has ten campuses.

- Arizona State University's College of Public Service & Community Solutions has conferred Bachelor of Social Work (BSW) and Master of Social Work (MSW) degrees for more than 30 years through its School of Social Work Tucson component.[159]

- Tucson College[160] has one Tucson campus.

- Brookline College has one Tucson campus.

- University of Phoenix has four Tucson campuses.

- Prescott College has a Tucson branch campus.

- Northern Arizona University has a Tucson branch campus.

- Arizona School of Acupuncture & Oriental Medicine[161]

- The Art Center Design College has two Tucson campuses.

- Wayland Baptist University has one Tucson campus.[162]

Primary and secondary schools[edit]

Primarily, students of the Tucson area attend public schools in the Tucson Unified School District (TUSD). TUSD has the second highest enrollment of any school district in Arizona, behind Mesa Unified School District in the Phoenix metropolitan area. There are also many publicly funded charter schools with a specialized curriculum.[163] Other notable districts include Sunnyside Unified School District, Marana Unified School District, Amphitheater Unified School District, and Flowing Wells Unified School District.

In 1956, Tucson High School had the largest enrollment of any secondary school in the United States, with a total of more than 6,800 students.[164] In 2018, Tucson High School enrollment was just over 3,000.

The facility operated on a two-shift basis while construction went on for two other high schools that opened within a year to educate children in the rapidly booming Tucson population.

Media[edit]

Print[edit]

Tucson has one daily newspaper, the morning Arizona Daily Star. Wick Communications publishes the daily legal paper The Daily Territorial, while Boulder, Colo.-based 10/13 Communications publishes Tucson Weekly (an "alternative" publication), Inside Tucson Business and the Explorer. TucsonSentinel.com is a nonprofit independent online news organization. Tucson Lifestyle Magazine, Lovin' Life in Tucson, DesertLeaf, and Zócalo Magazine are monthly publications covering arts, architecture, decor, fashion, entertainment, business, history, and other events. The Arizona Daily Wildcat is the University of Arizona's student newspaper, and the Aztec News is the Pima Community College student newspaper. Catholic Outlook is the newspaper for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson, and the Arizona Jewish Post is the newspaper of the Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona.

Television[edit]

The Tucson metro area is served by many local television stations and is the 65th largest designated market area (DMA) in the U.S. with 433,330 homes (0.39% of the total U.S.). It is limited to the three counties of southeastern Arizona (Pima, Santa Cruz, and Cochise)[165]

The major television networks serving Tucson are:

- KVOA 4 (NBC)

- KUAT-TV 6 is a PBS member station run by the University of Arizona (as is sister station KUAS 27).

- KGUN 9 (ABC)

- KMSB-TV 11 (Fox)

- KOLD-TV 13 (CBS)

- KUDF-LP 14 (Estrella TV)

- KTTU 18 (MyNetworkTV)

- KPCE-LD 29 (Daystar)

- KHRR-TV 40 (Telemundo)

- KUVE-DT 46 (Univision)

- KWBA-TV 58 (CW)

Infrastructure[edit]

Energy[edit]

Tucson's primary electrical power source is a natural gas power plant managed by Tucson Electric Power that is within the city limits on the southwestern boundary of Davis-Monthan Air-force base adjacent to Interstate 10. The air pollution generated has raised some concerns as the Sundt operating station has been online since 1962 and is exempt from many pollution standards and controls due to its age.[166] Solar has been gaining ground in Tucson with its ideal over 300 days of sunshine climate. Federal, state, and even local utility credits and incentives have also enticed residents to equip homes with solar systems. Davis-Monthan AFB has a 3.3 Megawatt (MW) ground-mounted solar photovoltaic (PV) array and a 2.7 MW rooftop-mounted PV array, both of which are in the Base Housing area. The base will soon have the largest solar-generating capacity in the United States Department of Defense after awarding a contract on September 10, 2010, to SunEdison to construct a 14.5 MW PV field on the northwestern side of the base.[167]

Global Solar Energy, which is at the University of Arizona's science and technology park, is one of the planet's largest CIGS solar fields at 750 kilowatts.[168][169]

Light pollution[edit]

Tucson and Pima County adopted dark sky ordinances to control light pollution in support of the region's astronomical observatories in 1972.[170] Last amended in 2012,[171] the City of Tucson/Pima County Outdoor Lighting Code establishes maximum illumination levels, shielding requirements, and limits on signage in "continuing support of astronomical activity and minimizing wasted energy, while not compromising the safety, security, and well-being of persons engaged in outdoor nighttime activities."[172]

Water[edit]

Less than 100 years ago, the Santa Cruz River flowed nearly year-round through Tucson. This supply of water has slowly disappeared, causing Tucson to seek alternative sources.

In 1881, water was pumped from a well on the banks of the Santa Cruz River and flowed by gravity through pipes into the distribution system.[173]

Tucson currently draws water from two main sources: Central Arizona Project (CAP) water and groundwater. In 1992, Tucson Water delivered CAP water to some customers that was unacceptable due to discoloration, bad odor and flavor, as well as problems it caused with some customers' plumbing and appliances. Tucson's city water currently consists of CAP water mixed with groundwater.

In an effort to conserve water, Tucson is recharging groundwater supplies by running part of its share of CAP water into various open portions of local rivers to seep into their aquifer.[174] Additional study is scheduled to determine how much water is lost through evaporation from the open areas, especially during the summer. The City of Tucson provides reclaimed water to its inhabitants, but it is only used for "applications such as irrigation, dust control, and industrial uses".[175] These resources have been in place for more than 27 years, and deliver to over 900 locations.[175]

To prevent further loss of groundwater, Tucson has been involved in water conservation and groundwater preservation efforts, shifting away from its reliance on a series of Tucson area wells in favor of conservation, consumption-based pricing for residential and commercial water use, and new wells in the more sustainable Avra Valley aquifer, northwest of the city. An allocation from the Central Arizona Project Aqueduct (CAP), which passes more than 300 mi (480 km) across the desert from the Colorado River, has been incorporated into the city's water supply, annually providing over 20 million gallons of "recharged" water which is pumped into the ground to replenish water pumped out.[176] Since 2001, CAP water has allowed the city to remove or turn off over 80 wells.[177]

Water harvesting[edit]