The Aesthetics of Resistance

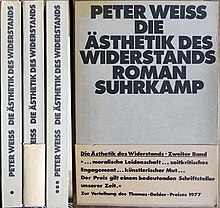

First editions (German) | |

| Author | Peter Weiss |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die Ästhetik des Widerstands |

| Translator | Joachim Neugroschel; Joel Scott |

| Genre | historical novel |

| Set in | Berlin from the 1930s through World War II |

Publication date | 1975 |

Published in English | 2005 |

| ISBN | 0822335344 |

| OCLC | 57193249 |

The Aesthetics of Resistance (German: Die Ästhetik des Widerstands, 1975–1981) is a three-volume novel by the German-born playwright, novelist, filmmaker, and painter Peter Weiss which was written over a ten-year period between 1971 and 1981. Spanning from the late 1930s into World War II, this historical novel dramatizes anti-fascist resistance and the rise and fall of proletarian political parties in Europe. It represents an attempt to bring to life and pass on the historical and social experiences and the aesthetic and political insights of the workers' movement in the years of resistance against fascism.

Living in Berlin in 1937, the unnamed narrator and his peers, sixteen and seventeen-year-old working-class students, seek ways to express their hatred for the Nazi regime. They meet in art museums and galleries, and in their discussions they explore the affinity between political resistance and art, the connection at the heart of Weiss's novel. Weiss suggests that meaning lies in the refusal to renounce resistance, no matter how intense the oppression, and that it is in art that new models of political action and social understanding are to be found. The novel includes extended meditations on paintings, sculpture, and literature. Moving from the Berlin underground to the front lines of the Spanish Civil War and on to other parts of Europe, the story teems with characters, almost all of whom are based on historical figures.

The three volumes of the novel were originally published in 1975, 1978 and 1981. English translations of volume I and II of the novel have been published by Duke University Press, respectively in 2005 and 2020.

Plot[edit]

Weiss's complex multi-layered 1000 page novel has been called a "book of the century [Jahrhundertbuch]."[1] It can no more be usefully summarized than James Joyce's Ulysses. By way of introducing The Aesthetics of Resistance what follows are the opening paragraphs of an article by Robert Cohen:

"The Aesthetics of Resistance begins with an absence. Missing is Heracles, the great hero of Greek mythology. The space he once occupied in the enormous stone frieze depicting the battle of the Giants against the Gods is empty. Some two thousand years ago the frieze covered the outer walls of the temple of Pergamon in Asia Minor. In the last third of the nineteenth century the remnants of the ancient monument were discovered by the German engineer Carl Humann and sent to Germany. The fragments were reassembled in the specially built Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the capital of Wilhelminian Germany, and were to signal from this point forward the late claims to power of German imperialism. The Pergamon frieze can still be seen in Berlin today. In the fall of 1937 – and here we are at the beginning of Peter Weiss's novel – three young men find themselves before the frieze. Two of them, Coppi and the narrator, whose name is never mentioned, are workers. The third, a sixteen-year-old named Heilmann, is a high school student. Coppi is a member of the illegal Communist Party, Heilmann and the narrator are sympathizers. All three are active in the antifascist resistance. In a lengthy discussion the three friends attempt to interpret the stone figures and events depicted in the frieze in a way which would make them relevant for their own present day struggle. They cannot, however, find Heracles. Other than a fragment of his name and the paw of a lion's skin, nothing remains of the leader of the Gods in the battle against the Giants. The "leader" of 1937, on the other hand, is an omnipresent force, even in the still halls of the Pergamon Museum, where uniformed SS troopers, their Nazi insignia clearly visible, mingle among the museum's visitors. Under the pressure of the present and with their lives in constant danger, the three young antifascists read the empty space in the frieze as an omen, they feel encouraged to fill it with their own representation of the absent half-god. What they envision is an alternative myth in stark contrast to the traditional image of Heracles. From a friend of the Gods, the mighty and the powerful, Heracles is transformed into a champion of the lowest classes, of the exploited, imprisoned, and tortured – a messianic "leader" in the struggle against the terror of the "Führer".

The concept of a messianic bearer of hope is by no means unique in Weiss's work. Starting with the coachman in the experimental novel The Shadow of the Body of the Coachman (1952/1959), messianic figures appear repeatedly in Weiss's literary work. That Weiss would continue to be obsessed with such figures after he turned to Marxism in 1964/1965 may seem surprising. However, the concept now becomes increasingly secularized, as for example in the figure of Empedocles in the play Hölderlin (1971). In The Aesthetics of Resistance this process of secularization is brought to its logical conclusion.

Before they reach this conclusion, however, readers of Weiss's novel are confronted with nearly a thousand pages of text interrupted only occasionally by a paragraph break – a sea of words which resists any attempt at summarizing. Even to characterize The Aesthetics of Resistance as an antifascist novel seems to unduly narrow the scope of Weiss's broad project. There is no clearly defined geographical or historical space within which events unfold. There is no unifying plot, and neither is there a chronological structure to the narrative. The novel presents a history of the European Left, from Marx and Engels to the post-war era, in countries as diverse as Germany and Sweden, the Soviet Union, France and Spain. Woven into the historical narratives and political discourses are extensive passages on works of art and literature from many centuries and from many European, and even non-European cultures – from the Pergamon frieze to the temple city of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, from Dürer and Brueghel to Géricault and Picasso, from Dante to Kafka, and from Surrealism and Dadaism to Socialist realism. The novel takes upon itself the enormous task of reinterpreting the great works of western culture from the perspective of the perennial victims of history and to fuse art and politics into one inseparable revolutionary unity.

In its final section the novel contains one of the great passages of world literature – a moment by moment description of the execution, by hanging or beheading, of almost all members of the resistance group "Red Orchestra" ("Rote Kapelle") in 1942 in Berlin's Plötzensee prison. All of the characters whose end Weiss describes here, indeed all of the characters who appear in The Aesthetics of Resistance, and there are hundreds, are actual historical figures. They bear their real names in the text, and everything that happens to them is based on verifiable facts which Weiss researched in many countries and numerous archives.[2] In its obsession with historical facts, as in other respects, The Aesthetics of Resistance is a work which transcends all boundaries.

The narrator – the only fictional character in the novel (he bears much resemblance to Peter Weiss) – is one of many nameless contributors to the activities of the Communist resistance. From 1937 to 1945 he wanders through much of Europe. His two friends, Heilmann and Coppi, remain in Berlin and eventually become members of the "Red Orchestra." From time to time a letter from Heilmann reaches the narrator. In his letters Heilmann continues his struggle for a reinterpretation of the Heracles myth. Amidst the reality of fascism and in a German capital laid waste by allied bombs, however, the notion of a messianic savior becomes less and less plausible. Coppi abandons it altogether. – Years after the war, long after Heilmann and Coppi had been hanged in Plötzensee – this, too, is historically authentic – the narrator once again finds himself before the Pergamon frieze in rebuilt Berlin. Heracles's place is still empty. There is no leader, no conceivable presence which can replace this absence. There is no hope for a messiah. No one other than the narrator himself and those like him can bring about their liberation. It is with this thought that the novel ends."[3]

Form features and structure[edit]

The three volumes of the work each consist of two parts, headed with the Roman numerals I and II. The text is divided neither into chapters nor paragraphs, but into paragraphless "blocks", which usually comprise about five to twenty printed pages[4] and are separated from each other by blank lines. Peter Weiss also dispenses with inverted commas, dashes, exclamation marks and question marks; punctuation thus consists only of full stops and commas. The latter are used primarily to structure the often long, paratactically constructed sentences. In phonetic and spelling terms, too, some of Weiss's peculiarities pervade all volumes: in particular, the regular omission of the unstressed e ("entstehn", "Pulvrisierung") and the spelling of years in two words with capitalised initials, e.g. Nineteen Hundred Thirty Seven ("Neunzehnhundert Siebenunddreißig").

Unlike in other experimental texts - such as James Joyce's or Gertrude Stein's works, however, the sentence constructions do conform to grammatical and pragmatic conventions. The text blocks are all established epic forms: Narrative report, description, reflection and direct or indirect, occasionally also experienced speech. A first-person narrator, who remains nameless until the end of the book, narrates the novel. The first-person narrator reports in chronological order what is experienced, perceived, felt and thought; jumps in the narrated time often occur because the first-person narrator refers to the speech of other persons, often with repetitive inquit formulas ("said my father"). In the second and especially in the third volume, the narrator increasingly recedes, longer and longer passages are reported from the perspective of other characters (especially Charlotte Bischoff). Nevertheless, the reporting and descriptive tone of the first-person narrator is maintained.

The time narrated covers a clearly defined period from 22 September 1937 to the year 1945. However, far-reaching retrospectives are brought into the plot through character speech and above all reflections by the narrator and other characters in the novel.

- The novel gains its distinctiveness from some striking structural elements such as the combination of historically authentic and fictional characters and the combination of narrative and reflexive sections, which has led to the apt designation 'novel-essay'. Another dominant feature are the extended dialogical passages, partly in direct, partly in indirect speech. They are the formal expression of a movement of thought that, in Brecht's succession, repeatedly attempts to articulate contradictory positions (in politics, ideology, aesthetics) and to set them against each other in such a way that they lead to new insights, consequences, changes. A similar function is assigned to the process of montage, with which Weiss confronts different places, times, figures and points of view with each other in a quasi-filmic way. On the other hand, the biographical narrative framework brings about, at least formally, a 'unity of contradictions'.[5]

History of origins and publication[edit]

Beginning[edit]

The first mention of the novel project is in Peter Weiss's notebooks, written in March 1972 as: "Seit Anfg. Okt. 71 Gedanken zum Roman" (Since began October 1971 Thoughts on the novel)[6] Weiss had not published fictional prose for at least eight years at that time. As a playwright, he had entered a crisis. His play Trotzki im Exil (Trotsky in Exile) had not been accepted in the GDR as it was considered anti-Soviet. Trotsky was a taboo subject for official communist historiography.[7] It had also had been scathingly criticised in West Germany. The author himself thought extensive changes to his play, Hölderlin (1971) were necessary, and he was busy working on them. The themes touched on in these plays, the history of socialist and communist oppositions and the relationship between art and politics, were taken up by Aesthetics of Resistance in a new form.

For the choice of the novel form, as Kurt Oesterle shows, a prehistory going back a long way is probably essential. Since the early 1960s, Weiss had repeatedly considered the plan of creating a work modelled on Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. Initially, he envisioned a dramatic cycle of works about the "world theatre" of oppression, but in the summer of 1969 he decided on a prose version and was already working on it. This project had two "monstrosities": "to represent the epoch in its totality" and "to do this by reflecting it in the consciousness and language of a single contemporary ..."[8] - for which only an epic form was suitable.

It is not only these formidable claims that connect the Divina Commedia project with the Aesthetics of Resistance - there are also numerous echoes in the text of the novel. Dante's work becomes the subject of art conversations in Aesthetics of Resistance, and motifs from the Divina Commedia underlie central passages of the novel, even to the point of direct quotation. Weiss himself has also described, among other things, Charlotte Bischoff's illegal trip to Germany in Volume 3 as a "Trip to Hades".[9] Thus it is at least "conceivable that Weiss's DC was absorbed into the resistance project - the remnant of a dowry from earlier years.[10]

Research[edit]

At the beginning of the actual work on the novel, Weiss carried out extensive research, which he continued throughout the entire duration of the work. At first, he concentrated on the characters who were exiled in Swedish, who later formed the protagonists of the second and third volumes. During 1972 for example, Weiss conducted interviews with Max Hodann's surviving relatives and his doctor, several of Bertolt Brecht's collaborators, Rosalinde von Ossietzky, the daughter of Nobel prize winner and journalist Carl von Ossietzky who was tortured to death by the Nazis and Maud von Ossietzky[11] along with resistance fighter Karl Mewis, resistance fighter Charlotte Bischoff, journalist and later a politician Herbert Wehner, committed communist and later a politician Paul Verner, communist journalist, later a diplomat Georg Henke, trade unionist Herbert Warnke, Ottora Maria Douglas, the sister of the resistance fighter and aristocrat Libertas Schulze-Boysen and Hans Coppi Jr., the son of resistance fighter Hans Coppi as well as with other contemporary witnesses, including various engineers from the Alfa Laval separator works, where the narrator worked for a time.[12] In addition, there was intensive archive study in numerous libraries. Above all, however, Weiss attached great importance to personally visiting the locations of the novel's plot.

In March–April 1974, Weiss took a trip to Spain to obtain authentic information about the places where Part 2 of Volume 1 is set. Among other things, Weiss discovered the remains of a mural in a storage room of the former headquarters of the Civil Guard in Albacete, that gave the visit an epic character,[13] which is described in detail in the novel. How important such impressions were to him can be seen, among other things, in the fact that he managed to discover the conspiratorial apartment of Communist International (Comintern) envoy Jakob Rosner in Stockholm shortly before the house was demolished, and that at the last moment he still incorporated current excavation results from Engelbrekt Engelbrektsson's time in Stockholm[12] into the already finished text of the second volume.

Writers block[edit]

On the 9 July 1972, Weiss made an entry in his Notizbücher (notebook) stating "Started the book",[14] that he made immediately after a visit to the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. Initially, Weiss only planned for one volume, to be entitled Der Widerstand (The Resistance). But Weiss encountered considerable difficulties, especially in connection with the figure of the first-person narrator. Twice in October 1972[14] and in April 1973 he began anew. He also reflected on the title again and again: in August 1973, the "unwieldy" title Die Ästhetik des Widerstands appeared in the notebooks for the first time. A letter from Suhrkamp director Siegfried Unseld still survives from April 1975, which says: "We have also agreed that the title of the novel should be 'The Resistance'."[15] It is not known how the final choice of title came about.

A vivid picture of the writing problems is conveyed by a quotation from the notebooks: "I can't manage this huge work, with all the disturbances and irritations. The heart begins to flicker again"[16] Again and again Weiss was compelled to interrupt the work, among other things by a hospital stay and his dramatisation of Franz Kafka's "The Trial". The author's nervousness and sensitivity to disturbances are also illustrated by repeated problems with motorboat drivers on the lake on which Weiss's weekend house was located, as well as a letter to Unseld, to whom he had sent the first part of the novel for review on 19 July 1974 "with some reservations". In this letter he complains bitterly about not having received any encouragement to continue.[17] Nevertheless, in July 1975 he managed to send the first volume to the publisher Suhrkamp Verlag, which appeared in September in a first edition of 3,500 copies.

The decision had long since been made to add a second volume, although the first edition did not yet contain any reference to it. Weiss also had to start this volume, whose Paris chapters were originally intended for volume 1, all over again in 1977. Again, the work was interrupted, this time by various political statements (such as on Wolf Biermann's expatriation, after being stripped him of his citizenship or the travel ban on Pavel Kohout) as well as the awarding of the Thomas Dehler Prize[18] by the Federal Ministry for Inner-German Relations, which caused him considerable misgivings.

The third volume[edit]

In 1978, Weiss and Unseld took the amicable decision to publish a shorter "epilogue volume" as the novel's conclusion. This third volume possibly cost Weiss even more effort than the first two, as he thought it had to be "the best" of the three volumes.[19] He soon rejected various attempts and complained in November 1978: "The pause before the epilogue volume has now lasted almost 5 months." [20] He completed the volume on 28 August 1980. Weakness prevented him from going through the publisher's corrections one by one.[21] He was forced to leave them to the Suhrkamp editor Elisabeth Borchers,[21] and finally approved the corrections by letter in summary form. This decision weighed heavily on Weiss, as is evident from his correspondence with Unseld. He ultimately raised no more objections, but asked that his concerns and further author corrections be taken into account for subsequent editions.[22] Suhrkamp Verlag initially did not comply with Weiss's request even after the author's death, except for minor corrections from June 1981 - the first edition had appeared in May - which did not change the make-up. It was not until the new edition of 2016 that Weiss's corrections were fully incorporated.[23]

Sweden and the GDR[edit]

While Weiss was working on the individual volumes, Ulrika Wallenström translated Aesthetics of Resistance into Swedish[24] for the small Swedish publishing house Arbetarkultur. Weiss organised this translation himself and also insisted to Suhrkamp that the Swedish rights (unlike all other Scandinavian rights) be kept out of the publishing contract. The bilingual author read the Swedish proofs himself and worked together with the translator. The Swedish individual volumes were each published by "Arbetarkultur" a few months after the German text.

In the GDR, however, the publication of the work proved difficult. At Weiss's request, Aufbau-Verlag received an offer for a GDR licensed edition immediately after the publication of the first volume, but did not respond for a full five months. Only when asked by Suhrkamp did the publishers explain that they wanted to wait for the second volume first. It was obviously political problems, especially the open portrayal of the struggles within the workers' movement, that justified this hesitant attitude. At least there was a preprint of a chapter of the second volume in the literary magazine Sinn und Form.[25]

It was not until 1981 that East Berlin's Henschelverlag, actually a theatrical publisher, succeeded in gaining the approval of GDR cultural politicians for a complete publication of all three volumes - subject to "enormous problems that the third volume could still bring"[26] (it had not yet appeared). Another round of editing followed with Manfred Haiduk, professor of literature at University of Rostock, who had long been a close friend with Weiss. In 1983, the entire work was finally published in the GDR in a first edition of no less than 5,000 copies,[27][26] which did not go into the general book trade but were specifically given to academics. A second edition in 1987 was exempt from such restrictions.

Other translations[edit]

In addition to the Swedish translation (Motståndets estetik, Stockholm 1976–1981), there are translations of all or individual volumes of Aesthetics of Resistance into

- Danish (Modstandens æstetik, Rosinante Munksgaard, Charlottenlund 1987–1988),

- English (The Aesthetics of Resistance, Duke University Press, Vol. 1, Durham, NC 2005; Vol. 2, Durham, NC 2020)

- French (L'esthétique de la résistance, Klincksieck, Paris 1989)

- Dutch (De esthetica van het verzet,Historische Uitgeverij, Groningen 2000)

- Norwegian (Motstandens estetikk, Pax, Oslo 1979)

- Spanish (La estâetica de la resistencia, Barcelona 1987)

- Turkish (Direnmenin Estetiği, Iletisim, İstanbul 2006)

Textual forms[edit]

Weiss typed his texts on large-format paper. The manuscript's have only small margins and already have the block-like character that also characterises the books. By rewriting and pasting over with cut-out parts of the text, the author avoided handwritten corrections directly in the text as far as possible. The typesetting for all three volumes is preserved in the Peter Weiss Archive, as well as a large number of drafts and cut text snippets from volumes 2 and 3.

After initial irritations, triggered in particular by the less than editor-friendly form of the typescripts, the sending of the typeset drafts was followed by fruitful and intensive editing at Suhrkamp Verlag, primarily by Elisabeth Borchers. Her concerns often concerned Scandinavianisms on the part of the author, whose daily vernacular was Swedish, and grammatical errors or problems. In the course of work on the third volume, however, friction grew considerably. Borchers and Unseld felt that the linguistic form needed significant revision, which distressed Weiss greatly. Although he acknowledged the criticism, he feared that the number of corrections was too great and that the interventions in his text went too far. Weiss stated of the experience:

- A reader may not even notice the editing of the text - perhaps he or she will even get the impression that the text runs better and more easily in this volume - but many idiosyncrasies, turns of phrase, "unruliness" keep coming to my attention in my manuscript, which have now been remedied, but which will bear witness to a "disempowerment" on my part in literary history. I have come to terms with this because, as I said, there was nothing I could do about the situation. I tell myself: the "original text" is still there, is still comparable. The peculiar disproportion between manuscript and book, however, continues to keep me in a state of unease.[28]

The GDR edition offered Weiss an opportunity to change this "peculiar disproportion". Weiss and Haiduk took over a large part of the Suhrkamp corrections, but reversed some deletions and substitutions and made further authorial and publishing corrections, much against the wishes of Unseld and Borchers. This affected the third volume in particular, but also some passages from the first volume that Weiss had noticed during a reading. Weiss expressly agreed to the final version as a last-hand edition.[29]

Now there were no less than three published versions approved by the author, two in German and one in Swedish. This could not remain hidden in the long run, especially since there had already been rumours of disputes between author and publisher. A systematic comparison of the versions has yet to be made, but the textual history and individual problems have been illuminated in various essays. In 1993, for example, Jens-Fietje Dwars compared the letter "Heilmann an Unbekannt", one of the last text blocks in volume 3, in the Urtext, Suhrkamp and Henschel versions.[30] It turns out that there is no question of political influence in either of the two book editions. But the Suhrkamp edition has a number of smoothings that have been taken back in the Henschel edition. For example, a passage describing bodily experiences of disgust has been significantly toned down in Suhrkamp and reinstated in Henschel in its full drasticness:

- ... the world of excrement, of malodorous acids, of blood, of nervous twitches, I was filled with it, there I lay ... (Suhrkamp version).

- ... the world of excrement, of viscera, of fetid acids, of tubes pumped with blood, of twitching nerve fibres, I was filled with it, there I lay in the slime, in the mud ... (Henschel version)[31]

Due to such deviations, Jürgen Schutte, the editor of the digital edition of Weiss's notebooks, called in 2008 for the creation of a critical edition of Aesthetics of Resistance, which would be based on the GDR version and would at least list the text variants of the published versions and the typeset drafts.[32] This is still pending. Nevertheless, a new edition by Schutte was published by Suhrkamp on 29 October 2016, which takes into account not only the published versions, but also Weiss's handwritten corrections to them as well as authorial corrections transmitted by letter, in order to create a reading edition that follows the author's "design intention" as far as possible.[33] It contains a short "Editorial Afterword" by Schutte, which lists the textual witnesses used.[34]

Artists and artworks in the novel[edit]

The multitude of artists and works of art that Peter Weiss has included in the novel, form a kind of musée imaginaire or (imagined museum), mainly consisting of the visual arts and literature, but also of the performing arts and music.[35] They are considered to be cultural traces that span an arc from antiquity to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, through works of Romanticism and Realism to the art of Expressionism and the avant-garde with its expression in Dadaism, Surrealism and Cubism. The diverse iconographic references are set in relation to the narrative of the history of the labour movement and resistance to fascism in Europe in the mid-20th century. The art-historical digressions reflect the inadequacy of proletarian education and the mechanisms of securing power by means of cultural incapacitation of the proletariat.[36]

Some of the works discussed, such as Dante Alighieri's Divina Commedia or Pablo Picasso's painting Guernica, and personalities sketched, such as the painter Théodore Géricault with his major work The Raft of the Medusa, occupy a central place in the plot. Others stand as examples of the first-person narrator's trains of thought or as enumerations in contexts of meaning; still others arise from the context. The novel is both an appreciation of resistance to Nazism and a plea for art as a necessity of life: "It is about resistance to mechanisms of oppression, as expressed in their most brutal, fascist form, and about the attempt to overcome a class-induced lockout from aesthetic goods."[37]

Divine Comedy[edit]

The Aesthetics of Resistance is highly influenced by Dante's early 14th-century verse narrative of the Divine Comedy.[38] As a work, it is introduced in the first part of the novel, in which the protagonists, who read and debate it together, perceive it as unsettling and rebellious.[39] With the commedia, Dante, as a first-person narrator, describes his journey through the three kingdoms of the afterlife, which takes him through the Inferno (Hell) with nine circles Hell, the Purgatorio (the purification realm or Purgatory) with seven penitential districts, and finally to the Paridiso (Paradise) with nine spheres of Heaven and its highest level, the Empyreum.

- "What happened here, we wondered since the summer of this year, when we had started our way into the strange, upside-down, sunk-in-the-earth dome, with its circles going deeper and deeper, and the duration of a life wanted to claim, while after the passage they still promised ascent, even ring by ring, to heights that were beyond the imaginable.

- – Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance, Volume I, page 79

In numerous motifs, allusions and mythical derivations, Peter Weiss repeatedly establishes the connection in the further course of the plot. The aesthetic organisation, the structure of the novel, can also be seen as a reference to the wandering through the realms of the beyond. This, in turn, is a process of cognition: "We learned what was consistent in us with Dante's poetry, learned why the origin of all art is memory.[40]

Central artworks[edit]

In addition to the Divine Comedy, it is above all Pablo Picasso's painting Guernica, created in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, at the end of the first volume and Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa, completed in 1819, in the first and at the beginning of the second volume that occupy central space in the discussions.[41] Both paintings are placed in the context of the artists' respective creative processes, their personal motifs, political backgrounds, correspondences from mythology, derivations from earlier works and influences on subsequent works. In particular, however, they are subjected to the question "What does it have to do with us".

Other paintings discussed in detail are Eugène Delacroix's The Liberty Leads the People, created after the July Revolution of 1830, Francisco Goya's The Shooting of the Insurgents, created in 1814, and Adolph Menzel's depiction The Iron Rolling Mill from 1875.

The plot opens with an eloquent description of the Pergamon Altar in Berlin's Pergamon Museum, which at the same time anticipates the content:

- We heard the blows of the clubs, the shrill whistles, the groans, the spurt of blood. We looked back into the past, and for a moment the perspective of what was to come was filled with a massacre that the thought of liberation could not penetrate.

- – Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance, Volume I, page 14

The motif is taken up conclusively at the end of the novel, so that it frames the narrative, so to speak.

Other buildings described in detail are the Sagrada Família basilica in Barcelona in the first volume and the temple complex of Angkor Wat in Cambodia in the third volume. Another literary work discussed in detail in the first volume is Franz Kafka's unfinished novel The Castle, published in 1922, and presented in the significant debate about the realist and avant-garde concepts of art.

Questions[edit]

The complexity of the relationship between resistance and aesthetics is already inherent in the double statement of the novel's title. The novel contains both narrative strands, it is to be read both under the aspect of "art as a form-giving function of resistance", i.e. the resistance of art (genitivus objectivus), and with a view to the "role of aesthetics for resistance" (genitivus subjectivus). The art receptions within the plot are seen as a broad, partisan reappraisal of the history of art, which is at the same time questioned through its own limited accessibility:

- It would have been presumptuous to want to talk about art without hearing the slurp as we put one foot in front of the other. Every meter towards the picture, the book, was a battle, we crawled, pushed, our eyelids blinked, sometimes we burst out laughing at those blinks, which made us forget where we were going.

- – Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance, Volume I, page 59

The symbol of this process is the figure of Heracles, which is the central motif. The hero from Greek mythology stands for his strength, with which he masters the tasks assigned to him. At the same time he achieved immortality because he fought on the side of the gods. In the novel he is symbolized as a controversial identification figure of the working class. Beginning with the question of why his image is missing from the frieze of the Pergamon Altar, the search for the true Heracles continues throughout the novel, culminating in the final scene.[42] On the basis of his myth, however, the relationship of the working class to art is also illustrated:

- Heracles, however, pulled his hat so hard over the eyes of Linus, the teacher who wanted to make his pupil believe that the only freedom there was was freedom of art, and when the magister maintained that the bridge of his nose broke Art is to be enjoyed at all times regardless of the current confusion, he sticks it upside down in the cesspool and drowns it, as proof that unarmed aesthetics cannot withstand the simplest violence.

- – Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance, Volume I, page 20

The fundamental question, however, which arises both in the content and in the execution of the aesthetics of resistance as a work of art, is whether the historical atrocities and horrors can be represented with artistic and literary means. Peter Weiss answers them by referring back to the works of art.

Reception[edit]

Mixed reactions in culture[edit]

Germany[edit]

The "Aesthetics of Resistance" received strong attention in the feuilletons or arts pages from the very beginning. All three volumes of the work were reviewed by prominent reviewers in the German-language daily and weekly newspapers shortly after publication. The response was mixed, however, with negative assessments predominating. This was especially true in the case of the first volume. In part, the authors referred to a formulation that Peter Weiss had used in an advance interview with the ZEIT editor Rolf Michaelis stating:

- "It is a wishful autobiography."[43]

Reinhard Baumgart in the Süddeutsche Zeitung reproached Weiss for passing off "a life dreamed in red" (the title of the review) as a novel.[44] Other authors also took more aim at Weiss's oft-published political confession than at the novel form itself, for example Moritz Menzel and Hans Christoph Buch in Der Spiegel.[45][46] While the first volume was only reviewed very positively by Alfred Andersch in the Frankfurter Rundschau (he coined the term "roman d'essai" or essay novel, which was later frequently used),[47] the subsequent volumes received more positive reviews, for example by Wolfram Schütte in the Frankfurter Rundschau and by Joachim Kaiser and Heinrich Vormweg in the Süddeutsche Zeitung.[48][49] At least Andersch, Schütte and Vormweg also evaluated the work's remembrance-political intention more than its formal realisation, as Martin Rector shows in his overview.[50]

Fritz J. Raddatz, one of the work's harshest critics, took a different stance, slating all three volumes in DIE ZEIT. He judged that Aesthetics of Resistance as a novel was an aberration, as it merely presented abstract, nonsensical, unpsychological figures and list-like enumerations ("Fascism as a crossword puzzle", "Bubbles from the flood of words", "Not a fresco, but a patchwork carpet").[51][52][53] Hanjo Kesting argued exactly the opposite in Der Spiegel: it is precisely the break with genre traditions that makes the work valuable; moreover, all interpretations that equate the aesthetics of resistance with the positions represented in it fall short, because the actual theme of the novel is the self-discovery of the first-person narrator as an artist.[54] According to the literary scholar Klaus R. Scherpe writing in the Weimarer Beiträge eurocommunist journal, at the beginning of 1978, that Günter Platzdasch was attempting to bring the work to the attention of the left "for critical self-understanding".[55]

The author and academic W.G. Sebald stated towards the end of On The Natural History of Destruction

- "[The Aesthetics of Resistance]...which [Peter Weiss] began when he was well over fifty, making a pilgrimage over the arid slopes of cultural and contemporary history in the company of pavor nocturnus, the terror of the night, and laden with a monstrous weight of ideological ballast, is a magnam opus which sees itself...not only as the expression of an ephemeral wish for redemption, but as an expression of the will to be on the side of the victims at the end of time.".[56]

Worldwide[edit]

The "Aesthetics of Resistance" was reviewed by many prominent literary and political publishers in Europe and the world. When Duke University Press published the first volume in a new English translation in 2005, it led to many modern reviews being written. In July 2006, academic Inez Hedges of Northeastern University responded by a review in the Marxist Socialism and Democracy.[57]

The French left-wing newspaper "Libération" gave a largely robust review in 2017, that quotes the books extensively, and makes particular note of the Red Orchestra, stating,

- "The astonishing total force of the Aesthetics of Resistance, of which various passages can recall Robert Walser or Thomas Bernhard, is also due to its romantic character, to the parade of characters who each bring their world to life, their convictions and the ways of living in it. being loyal.[58]

The new French cultural magazine, "Diacritik" that was established in 2015,[59] wrote a review in 2017 that first laments the lack of a French edition, then provides a new introduction to the work with the main elements introduced, for example the Red Orchestra, in a review that largely descriptive of the main themes with some analysis.[60] The novel continues to be reviewed in the modern context. In 2020, Julian Murphet, an academic from the University of Adelaide, wrote a review on the second volume translation, in the series, that was published in March 2020, for the Sydney Review of Books.[61] The review posits the second volume as a Bildungsroman.[61] In 2021, André Fischer of the Washington University in St. Louis, US, examined the aesthetic and iconological implications of Weiss's use of the Heracles myth through readings of French theorist, Georges Sorel's theory of social myth.[62]

Reading groups[edit]

More remarkable, however, was a collective reception of the novel in a large number of reading groups that can be attributed to the political left. A kind of initial spark for this form of reception was the Berlin Volks-Uni in 1981, where a whole series of reading groups had already come together, partly made up of students and lecturers, but also partly from non-university, especially left-wing trade union circles. They received the work together and talked about it at regular meetings. How many such reading circles there were has not been researched, but there are numerous references to them. For example, the University of Bremen literature lecturer Thomas Metscher reported on regular camps of the Friends of Nature (Naturfreundejugen) in the Allgäu region, where the Aesthetics of Resistance was read,[63] and Martin Rector quotes a transcript of one such reading circle, in which, among others, educators, masseurs, typesetters and booksellers took part, from Literatur konkret 6 (1981/82):

- "In one group we have been reading Peter Weiss' Aesthetics of Resistance for a year. ... Non-academics and dependent employees are in the majority, people whose story the Aesthetics of Resistance is about, even if in a way that was previously unfamiliar to us.[64]

There were also numerous groups around German studies lecturers at various universities who had similar collective reading experiences - Rector, who himself was one of them, lists no fewer than seven universities. Such groups are also documented in the East Germany, where the work was only available with difficulty and was partly copied from borrowed copies, especially at the Humboldt University of Berlin and the University of Jena. An interdisciplinary lecture series on this work took place in Berlin in 1984–85, which was subsequently documented in an anthology. Such anthologies were published in large numbers by university reading groups in the 1980s.

Intermedial Reception[edit]

The filmmaker Harun Farocki held a conversation with Peter Weiss in Stockholm on 17 June 1979[65] about the process of creating the third volume of Aesthetics of Resistance, which formed the basis of the film documentary Zur Ansicht: Peter Weiss.[66] Farocki's film was screened at the Berlin International Film Festival in February 1980 and published in 2012 as volume 30 of the "filmedition suhrkamp" magazine (Peter Weiss. Films). In December 1984, the exhibition "Traces of the Aesthetics of Resistance" was shown at the West Berlin Berlin University of the Arts, which dealt with Weiss's work, among other things.[67] In later years, there were further exhibitions showing artistic works on Weiss's novel and its central topos. Several visual artists such as Fritz Cremer,[68] Hubertus Giebe or Rainer Wölzl and composers such as the Finnish Blacher student Kalevi Aho,[69] the Villa Massimo scholarship holder Helmut Oehring or the Dessau student Friedrich Schenker drew on motifs from Aesthetics of Resistance in their works.

The novel has been adapted for the stage by Thomas Krupa and Tilman Neuffer at Grillo-Theater Essen in May 2012.[70] The adaptors reduced the voluminous novel to almost 50 scenes. The approximately three-and-a-half-hour play version, which was realised with eleven actors, concentrated mainly on the first and third volumes of Weiss's novel and emphasised the elements of the original, which were designed in a surreal dream language.[71] While some critics praised a theatrically effective, lightly paced and painfully precise play against oblivion, others saw the project as overtaxing the theatre in view of the abundance of material, missed approaches to updating or criticised an incongruence between Weiss's experimental narrative technique and the adaptors' restriction to classical stage dialogue.[72] The creation of the Essen stage version is the subject of the documentary film Uraufführung: Vom Buch zur Bühne by the production company Siegersbusch, which premiered in Essen in April 2013.

In 2007, a 630-minute radio play version was published[73] with Robert Stadlober and Peter Fricke as narrators,[74] which was voted Audiobook of the Year 2007. Karl Bruckmaier was responsible for the direction and radio play adaptation.[74] The editorship was shared by Herbert Kapfer for Bayerischer Rundfunk and Wolfgang Schiffer for Westdeutscher Rundfunk.

Projects based on text sequences from The Aesthetics of Resistance also emerged in the independent film and theatre scene, including the theatre project Passage. Three plays from "The Aesthetics of Resistance", adopted by Johannes Thorbecke for the theatre Gegendruck premiered in Bochum on 30 September 2012.[75] The approximately one-and-a-half-hour film VidaExtra by the independent Galician filmmaker Ramiro Ledo Cordeiro, which premiered in Buenos Aires in April 2013. The film links excerpts from The Aesthetics of Resistance to the events surrounding the euro crisis.[76]

The band Rome was inspired by the novels when making their concept album trilogy Die Æsthetik Der Herrschaftsfreiheit.[77] In addition to works by Bertolt Brecht, Friedrich Nietzsche, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and others, the album also draws on motifs from The Aesthetics of Resistance. Swedish death metal band At the Gates were inspired by The Aesthetics of Resistance on their album To Drink from the Night Itself.

Radio play[edit]

The Aesthetics of Resistance, a radio play in 12 parts:

- Robert Stadlober, Peter Fricke, Helga Fellerer, Ulrich Frank, Paul Herwig, Rüdiger Vogler, Michael Troger, Helmut Stange, Christian Friedel, Stephan Zinner, Katharina Schubert, Sabine Kastius, Susanne-Marie Wrage, Hanns Zischler, Jochen Striebeck, Wolfgang Hinze, Jule Ronstedt (2007). Die Ästhetik des Widerstands : Hörspiel (Stage Play) (in German). Der Hörverlag. ISBN 9783867170147. OCLC 1080919830.

Directed and adapted by Karl Bruckmaier. Composition by David Grubbs. Editing and direction by Karl Bruckmaier

As a podcast, all 12 parts are available in the BR Hörspiel Pool.[78]

Film[edit]

- Farocki, Harun (1979). Zur Ansicht:Peter Weiss [On view:Peter Weiss] (Documentary) (in German). Berlin: Harun Farocki Filmproduktion.

Musical recordings[edit]

- Aho, Kalevi (August 1994). Symphony No. 8 Pergamon. BIS.

Cantata for 4 orchestral groups, 4 reciters and organ. The first performance was in Helsinki on 1 September 1990. It was commissioned by the University of Helsinki for the 350th anniversary of the university. The text is mainly taken from the beginning of The Aesthetics of Resistance. The four reciters read the three text excerpts simultaneously in four languages: German, Finnish, Swedish and Ancient Greek.

- Brass, Nikolaus (2006). fallacies of hope – Deutsches Requiem. Ricordi Berlin.

Music for 32 voices in 4 groups with text projection (ad libitum)

- Oehring, Helmut (27 November 2008). Quixote oder Die Porzellanlanze. Dresden: Ricordi Berlin.

Based on motifs from the first volume of Aesthetics of Resistance. The first performance was at the Festspielhaus Hellerau

- Oehring, Helmut (27 November 2008). Quixote oder Die Porzellanlanze. Dresden: Ricordi Berlin.

Based on motifs from the first volume of Aesthetics of Resistance. The first performance was at the Festspielhaus Hellerau

- Rome (2012). Die Æsthetik Der Herrschaftsfreiheite. Dresden: Trisol Music Group.

Chanson noire/concept album based on motifs from Aesthetics of Resistance and other

- Friedrich, Schenker (16 January 2013). Ästhetik des Widerstands 1 für Baßklarinette und Ensemble. Dresden.

String quartet, flute, trombone, piano, percussion. Premiere at the Gewandhaus concert hall in Leipzig, 16 January 201 and commissioned by them.

- Stäbler, Gerhard; Maingardt, Sergej (24 January 2016). The Raft - Das Floss.

See also[edit]

Literature[edit]

- Badenberg, Nana (1995). "Die „Ästhetik" und ihre Kunstwerke". In Honold, Alexander; Schreiber, Ulrich (eds.). Die Bilderwelt des Peter Weiss. Berlin: Edition Hentrich. pp. 114–162. ISBN 3-88619-227-X.

- Beise, Arnd (2008). Birkmeyer, Jens; Hofmann, Michael (eds.). Diese bebende, zähe, kühne Hoffnung : 25 Jahre Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (in German). St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. ISBN 978-3-86110-438-4. OCLC 244019378.

- Clare, Jennifer (2016). Protexte Interaktionen von literarischen Schreibprozessen und politischer Opposition um 1968. Lettre (Transcript (Firm)) (in German). Bielefeld. ISBN 978-3-8376-3283-5. OCLC 944386556.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cohen, Robert (1989). Bio-bibliographisches Handbuch zu Peter Weiss' "Ästhetik des Widerstands". Hamburg: Argument. ISBN 3-88619-771-9. OCLC 243393388.

- Cohen, Robert (1999). "Nonrational discourse in a work of reason". In Peitsch, Helmut; Burdett, Charles; Gorrara, Claire (eds.). European memories of the Second World War (1st ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 272–280. ISBN 9781845451585.

- Dwars, Jens-F; Strützel, Dieter; Mieth, Matias (1993). Widerstand wahrnehmen : Dokumente eines Dialogs mit Peter Weiss (in German) (1st ed.). Köln: GNN. ISBN 3-926922-16-8.

- Götze, Karl-Heinz (1981). Scherpe, Klaus R. (ed.). Die "Ästhetik des Widerstands" lesen : über Peter Weiss. Argument /, Sonderband ;, 75.; Literatur im historischen Prozeß, 1. (in German). Berlin: Argument-Verlag. ISBN 3-88619-026-9. OCLC 695406518.

- Groscurth, Steffen (2014). Fluchtpunkte widerständiger Ästhetik : zur Entstehung von Peter Weiss' ästhetischer Theorie. Spectrum Literaturwissenschaft : komparatistische Studien = Spectrum literature : comparative studies. Vol. 41. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-034554-4. OCLC 994768435.

- Hell, Julie (2001). "From Laokoon to Ge: Resistance to Jewish Authorship". In Hermand, Jost; Silberman, Marc (eds.). Rethinking Peter Weiss. German life and civilization. Vol. 32. New York: P. Lang. pp. 21–44. ISBN 9780820448510. OCLC 469955655.

- Hofmann, Michael (1990). Ästhetische Erfahrung in der historischen Krise : eine Untersuchung zum Kunst- und Literaturverständnis in Peter Weiss' Roman "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands". Bonner Arbeiten zur deutschen Literatur, 45 (in German). Bonn: Bouvier. ISBN 3416022289. OCLC 243410164.

- Honold, Alexander (2005). "Weltlandschaft am Küchentisch. Die Ästhetik des Widerstands als enzyklopädische Narration". In Wiethölter, Waltraud; Berndt, Frauke; Kammer, Stephan (eds.). Vom Weltbuch bis zum World Wide Web : enzyklopädische Literaturen : [interdisziplinäre Vortrags- und Kolloquienreihe des Sommers 2003]. Neues Forum für allgemeine und vergleichende Literaturwissenschaft, 21. Heidelberg: Edition Hentrich. pp. 265–286. ISBN 3-8253-1582-7. OCLC 496773835.

- Langston, Richard (July 2008). "The Work of Art as Theory of Work: Relationality in the Works of Weiss and Negt & Kluge". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 83 (3): 195–216. doi:10.3200/GERR.83.3.195-216. S2CID 162051478.

- Lindner, Burkhardt; Springman, Luke; Kepple, Amy (1983). "Hallucinatory Realism: Peter Weiss' Aesthetics of Resistance, Notebooks, and the Death Zones of Art". New German Critique (30): 127–156. doi:10.2307/487836. JSTOR 487836.

- Lüdke, Werner Martin (1991). Schmidt, Delf (ed.). Widerstand der Ästhetik? : im Anschluss an Peter Weiss. Literaturmagazin, 27. (1st ed.). Hamburg: Rowohlt. ISBN 3-498-03867-2. OCLC 988343028.

- Scherpe, Klaus R.; Gussen, James (1983). "Reading the Aesthetics of Resistance: Ten Working Theses". New German Critique. 30 (30). Duke University Press: 97–105. doi:10.2307/487834. JSTOR 487834. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- Schutte, Jürgen; Hauff, Axel; Nadolny, Stefan (2018). Register zur Ästhetik des Widerstands von Peter Weiss. Lfb-Texte, 8 (in German) (1st ed.). Berlin: Verbrecher Verlag. ISBN 978-3-957-32341-5. OCLC 1146428230.

- Weiss, Peter (1982). Notizbücher, 1971-1980 Part 1. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067: N.F., 67 (in German). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Berlin: Suhrkamp. ISBN 9783518110676. OCLC 938783091.

- Weiss, Peter (1982). Notizbücher, 1971-1980 Part 2. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067: N.F., 67 (in German). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. ISBN 9783518110676. OCLC 938783091.

- Willner, Jenny (2014). Wortgewalt : Peter Weiss und die deutsche Sprache. Konstanz: Konstanz University Press. pp. 251–363. ISBN 978-3-86253-040-3. OCLC 997418332.

Thesis[edit]

- Cottier, Nigel (2010). Totality and the Sublime in Peter Weiss's The Aesthetics of Resistance A Proletarian Phenomenology (Thesis) (in German). VDM Verlag. ISBN 9783639058604. OCLC 724054905.

- Groscurth, Steffen (2014). Fluchtpunkte widerständiger Ästhetik : zur Entstehung von Peter Weiss' ästhetischer Theorie (Thesis). Spectrum Literaturwissenschaft, 41. (in German). Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-034554-4. OCLC 881290547.

- Nam, Duk-Hyun (2003). Die politische Ästhetik der Beschreibung [The political aesthetics of description] (Thesis) (in German). Free University of Berlin.

- Oesterle, Kurt (1989). Untersuchungen zu Peter Weiss' Grundlegung einer Ästetik des Wiederstands [Investigations into Peter Weiss' Groundwork for an Aesthetics of Resistance] (Thesis) (in German). Tübingen: University of Tübingen. ISBN 3-935915-00-4.

- Rump, Bernd (1996). Herrschaft und Widerstand : Untersuchungen zu Genesis und Eigenart des kulturphilosophischen Diskurses in dem Roman "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands" von Peter Weiss [Domination and resistance: Investigations on the genesis and character of the cultural-philosophical discourse in the novel "The Aesthetics of Resistance" by Peter Weiss] (Thesis). Sprache & Kultur (in German). Aachen: Shaker. ISBN 9783826517303. OCLC 845246354.

English editions in print[edit]

- Weiss, Peter (2005). The Aesthetics of resistance, Volume I. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822335467. OCLC 742195331. Translated by Joachim Neugroschel. With a foreword by Fredric Jameson and a glossary by Robert Cohen.

- Weiss, Peter (March 2020). The aesthetics of resistance, Volume II. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 9781478006145. OCLC 1229478379. Translated by Joel Scott, Afterword to the New Berlin Edition by Jürgen Schutte

GDR reception[edit]

- Crome, Erhard; Kirschner, Lutz; Land, Rainer (1999). Die Wunde bleibt offen. Der Peter-Weiß-Kreís in Jena [The wound remains open. The Peter Weiss Circle in Jena] (PDF) (in German). Berlin: Gesellschaft für sozialwissenschaftliche Forschung und Publizistik mbH. pp. 9–17.

Abschlußbericht zum DFG-Projekt CR 93/1-1 Der SED-Reformdiskurs der achtziger Jahre Dokumentation und Rekonstruktion kommunikativer Netzwerke und zeitlicher Abläufe Analyse der Spezifik und der Differenzen zu anderen Reformdiskursen der SED (Final Report on the DFG Project CR 93/1-1 The SED Reform Discourse of the Eighties Documentation and reconstruction of communicative networks and temporal processes Analysis of the specifics and differences to other reform discourses of the SED)

References[edit]

- ^ Wolfgang Fritz Haug and Kaspar Maase, "Vorwort." Materialistische Kulturtheorie und Alltagskultur. Haug/Maase (eds.). Argument Verlag, 1980, p. 4.

- ^ For biographical information on the figures in The Aesthetics of Resistance, an index of names, a chronology and other information on the novel see Robert Cohen: Bio-bibliographisches Handbuch zu Weiss' Ästhetik des Widerstands. Argument Verlag, 1989.

- ^ Robert Cohen: "Nonrational Discourse in a Work of Reason: Peter Weiss's Antifascist Novel Die Ästhetik des Widerstands." European Memories of the Second World War. Helmut Peitsch, Charles Burdett, and Claire Gorrara (eds.). Berghahn Books, 1999. 272-75

- ^ Beausang, Chris (16 May 2021). "Peter Weiss The Aesthetics of Resistance, Volume II Review". Marx and Philosophy Review of Books. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Vogt, Jochen (2003). "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands". In Kaiser, Joachim (ed.). Harenberg : das Buch der 1000 Bücher : Autoren, Geschichte, Inhalt und Wirkung. Dortmund: Harenberg, cop. ISBN 9783611010590. OCLC 907116870.

- ^ Abrantes, Ana Margarida; Lang, Peter (2010). Meaning and mind : a cognitive approach to Peter Weiss' prose work. Passagem. Vol. 3. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. p. 255. ISBN 9783631595930.

- ^ Berwald, Olaf (2003). An Introduction to the Works of Peter Weiss. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture. Rochester: Camden House. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-57113-232-1. OCLC 926773359.

- ^ Lüdke, Werner Martin; Schmidt, Delf (1991). "Kurt Oesterle: Dante und das Mega-Ich. Literarische Formen politischer und ästhetischer Subjektivität bei Peter Weiss". Widerstand der Ästhetik? : im Anschluss an Peter Weiss (in German) (Erstausg ed.). Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. pp. 45–72, 55. ISBN 9783498038670.

- ^ Rector, Martin; Vogt, Jochen (1996). Peter Weiss Jahrbuch 5 (in German). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-531-12907-5.

- ^ Lüdke, Werner Martin; Schmidt, Delf (1991). "Kurt Oesterle: Dante und das Mega-Ich. Literarische Formen politischer und ästhetischer Subjektivität bei Peter Weiss". Widerstand der Ästhetik? : im Anschluss an Peter Weiss (in German) (Erstausg ed.). Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. pp. 45–72, 65. ISBN 9783498038670.

- ^ Cohen, Robert (1993). Understanding Peter Weiss. Understanding modern European and Latin American literature. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-87249-898-3. OCLC 1295961658.

- ^ a b Lindner, Burkhardt; Springman, Luke; Kepple, Amy (1983). "Hallucinatory Realism: Peter Weiss' Aesthetics of Resistance, Notebooks, and the Death Zones of Art". New German Critique. 30 (30). Duke University Press: 127–156. doi:10.2307/487836. JSTOR 487836.

- ^ Guerra, Carles (19 February 2011). "La última novela épica". Libros (in Spanish). Barcelona: Javier Godó. La Vanguardia. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b Howald, Stefan (1994). Peter Weiss zur Einführung (in German). Hamburg: Junius. p. 135. ISBN 9783885069010. OCLC 902352645.

- ^ Unseld, Siegfried; Gerlach, Rainer; Weiss, Peter (2007). Der Briefwechsel (in German) (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. p. 911. ISBN 978-3-518-41845-1.

Unseld's letter to Weiss of 28 April 1975

- ^ Weiss, Peter (1982). Notizbücher, 1971-1980 Part 1. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067: N.F., 67 (in German). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Berlin: Suhrkamp. p. 246. ISBN 9783518110676. OCLC 938783091.

- ^ Unseld, Siegfried; Gerlach, Rainer; Weiss, Peter (2007). Der Briefwechsel (in German) (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. p. 888. ISBN 9783518418451. OCLC 939997412.

- ^ Berwald, Olaf (2003). An Introduction to the Works of Peter Weiss. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture. Rochester, NY: Camden House. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-57113-232-1. OCLC 926773359.

- ^ Unseld, Siegfried; Gerlach, Rainer; Weiss, Peter (2007). Der Briefwechsel (in German) (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. p. 1018. ISBN 9783518418451. OCLC 939997412.

- ^ Weiss, Peter (1982). Notizbücher, 1971-1980 Part 2. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067: N.F., 67 (in German). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. pp. 756–757. ISBN 9783518110676. OCLC 938783091.

- ^ a b Gerlach, Rainer (2005). Die Bedeutung des Suhrkamp Verlags für das Werk von Peter Weiss. Kunst und Gesellschaft, Band 1 (in German). St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. ISBN 978-3-86110-375-2. OCLC 470357269.

Thesis

- ^ Beise, Arnd; Birkmeyer, Jens; Hofmann, Michael (2008). Diese bebende, zähe, kühne Hoffnung: 25 Jahre Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (in German). Röhrig Universitätsverlag. p. 51. ISBN 978-3-86110-438-4.

- ^ Weiss, Peter (18 February 2020). The Aesthetics of Resistance, Volume II: A Novel, Volume 2. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-1-4780-0756-2.

Jürgen Schutte describes the details of the New Berlin edition in 2016 with the corrections, in the afterword

- ^ "Gerard Bonniers pris". Svenska Akademien (in Swedish). Stockholm: Svenska Akademien 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Weimann, Robert (1984). "Avantgarde - Arbeiterklasse - Erbe. Gespräch zu Peter Weiss´ »Die Ästhetik des Widerstands". Sinn und Form (in German) (1). Berlin: 68.

- ^ a b Unseld, Siegfried; Gerlach, Rainer; Weiss, Peter (2007). Der Briefwechsel (in German) (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. p. 1071. ISBN 978-3-518-41845-1.

Telephone note by Elisabeth Borchers of 18 February 1981

- ^ Dwars, Jens-F. (2007). Und dennoch Hoffnung : Peter Weiss : eine Biographie (1st ed.). Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag. p. 254. ISBN 978-3351026370.

- ^ Unseld, Siegfried; Gerlach, Rainer; Weiss, Peter (2007). Der Briefwechsel (in German) (1st ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. p. 1063. ISBN 978-3-518-41845-1.

Letter to Unseld of 31 January 1981.The peculiar punctuation is taken from Gerlach's book edition

- ^ Landgren, Gustav (30 September 2016). Rauswühlen, rauskratzen aus einer Masse von Schutt: Zum Verhältnis von Stadt und Erinnerung im Werk von Peter Weiss (in German). Stockholm: transcript Verlag. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-8394-3618-9.

- ^ Beise, Arnd; Birkmeyer, Jens; Hofmann, Michael (2008). Diese bebende, zähe, kühne Hoffnung: 25 Jahre Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (in German). Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-3-86110-438-4.

- ^ Dwars, Jens-Fietje (1993). Strützel, Dieter; Mieth, Matias; Weiss, Peter (eds.). Widerstand wahrnehmen : Dokumente eines Dialogs mit Peter Weiss (in German). Köln: GNN-Verlag. pp. 256–285. ISBN 9783926922168.

The quoted passage can be found at Suhrkamp on p. 205, at Henschel on p. 212 of the third volume.

- ^ Schutte, Jürgen (2008). "Für eine Kritische Ausgabe der Ästhetik des Widerstands". In Birkmeyer, Jens; Hofmann, Michael (eds.). Diese bebende, zähe, kühne Hoffnung : 25 Jahre Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (in German). St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 49–75. ISBN 978-3-86110-438-4. OCLC 244019378.

- ^ Weiss, Peter (2016). Schutte, Jürgen (ed.). The Aesthetics of Resistance (in German). Berlin: Suhrkamp. pp. 1197–1199, 1199.

- ^ Reichelt, Matthias (22 October 2016). "Peter Weiss hat die DDR immer sehr kritisch eingeschätzt" (in German). Verlag 8. Mai GmbH. Junge Welt. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

Conversation. With Jürgen Schutte. On the significance of the "Aesthetics of Resistance", corrections to the text and its reception history.

- ^ Badenberg, Nana (1995). "Die Ästhetik und ihre Kunstwerke. Eine Inventur". In Honold, Alexander; Schreiber, Ulrich; Badenberg, Nana (eds.). Die Bilderwelt des Peter Weiss (in German) (1st ed.). Hamburg: Argument-Verlag. p. 115. ISBN 9783886192274.

- ^ Birkmeyer, Jens (1992). Bilder des Schreckens : Dantes Spuren und die Mythosrezeption in Peter Weiss´ Roman "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands" (PDF) (Thesis) (in German). Goethe University Frankfurt. p. 96. ISBN 9783639058604. OCLC 724054905.

- ^ Weiss, Peter (1982). Notizbücher, 1971-1980 Part 1. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067: N.F., 67 (in German). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Berlin: Suhrkamp. p. 419. ISBN 9783518110676. OCLC 938783091.

- ^ Kirsch, Adam (14 January 2021). "The People's Novel". The New York Review of Books. New York. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Pike, David L. (5 September 2018). Passage through Hell: Modernist Descents, Medieval Underworlds. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-5017-2947-8.

- ^ Weiss, Peter (1982). Notizbücher, 1971-1980 Part 1. Edition Suhrkamp, 1067: N.F., 67 (in German). Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Berlin: Suhrkamp. p. 223. ISBN 9783518110676. OCLC 938783091.

- ^ Huyssen, Andreas (1986). After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-253-20399-1.

- ^ Birkmeyer, Jens (1992). Bilder des Schreckens : Dantes Spuren und die Mythosrezeption in Peter Weiss´ Roman "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands" (PDF) (Thesis) (in German). Goethe University Frankfurt. p. 8. ISBN 9783639058604. OCLC 724054905.

- ^ "Es ist eine Wunschautobiographie". No. 42. Die Zeit. 10 October 1975. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Baumgart, Reinhard (26 October 1975). "Ein rot geträumtes Leben" (in German). Südwestdeutsche Medien Holding. Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ Menzel, Moritz (23 November 1975). "Kopfstand mit Kunst". No. 48. Spiegel-Verlag. Der Spiegel. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Buch, Hans Christoph (19 November 1978). "Seine Rede ist: Ja ja, nein nein" (in German). Spiegel-Verlag. Der Spiegel. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Andersch, Alfred (20 September 1975). "Wie man widersteht. Reichtum und Tiefe von Peter Weiss" (in German). Frankfurt. Frankfurter Rundschau.

- ^ Kaiser, Joachim (28 November 1975). "Die Seele und die Partei" (in German). Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ Vormweg, Heinrich (19 May 1981). "Ein großer Entwurf gegen den Zeitgeist" (in German). Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ Rector, Martin (2008). "Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Die Ästhetik des Widerstands. Prolegomena zu einem Forschungsbericht". In Birkmeyer, Jens; Hofmann, Michael (eds.). Diese bebende, zähe, kühne Hoffnung : 25 Jahre Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (in German). St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 13–47. ISBN 978-3-86110-438-4. OCLC 244019378.

- ^ Raddatz, Fritz J. (10 October 1975). "Faschismus als Kreuzworträtsel Peter Weiss: "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands" (in German). Zeit-Verlag Gerd Bucerius GmbH & Co. KG. Die Ziet. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Raddatz, Fritz J. (17 November 1978). "Blasen aus der Wort-Flut Der zweite Band von Peter Weiss: "Aesthetik des Widerstands"" (in German). Zeit-Verlag Gerd Bucerius GmbH & Co. KG. Die Ziet. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Raddatz, Fritz J. (8 May 1981). "Abschied von den Söhnen? Peter Weiss: "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands"" (in German). Zeit-Verlag Gerd Bucerius GmbH & Co. KG. Die Ziet. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Kesting, Hanjo (7 June 1981). "Hanjo Kesting über Peter Weiss: »Die Ästhetik des Widerstands« Die Ruinen eines Zeitalters Hanjo Kesting, 38, ist Literaturredakteur beim NDR in Hannover" (in German). Spiegel-Verlag. Der Spiegel. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Scherpe, Klaus R (1978). "Peter Weiss: "Die Ästhetik des Widerstands". Erster Band. Antworten eines lesenden Arbeiters?". Weimarer Beiträge (in German). Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg: 155–163.

- ^ Ionescu, Arleen; Margaroni, Maria (22 June 2020). Arts of Healing: Cultural Narratives of Trauma. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-78661-098-0.

- ^ Hedges, Inez (July 2006). "The Aesthetics of Resistance: Thoughts on Peter Weiss". Socialism and Democracy. 20 (2): 69–77. doi:10.1080/08854300600691608. S2CID 144455199.

- ^ Lindon, Mathieu (30 June 2017). "Peter Weiss résiste et saigne" (in French). Libération. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Barthes, Roland. "Diacritik !?" (in French). Diacritik. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Rass, Martin (18 August 2017). "Peter Weiss : " Je ne l'ai jamais embrassée. Nous sommes restés moralistes, n'est-ce pas " (L'esthétique de la résistance)". Diacritik. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ a b Murphet, Julian (March 2020). "Named and Nameless Others". The Sydney Review of Books. Sydney: Western Sydney University, Australia Council of the Arts, Create NSW. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Fischer, André (2 January 2022). "Mythos and Pathos: Herakles in Peter Weiss's The Aesthetics of Resistance". The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory. 97 (1): 69–91. doi:10.1080/00168890.2021.2019663. S2CID 248671566.

- ^ Metscher, Thomas (1984). "History in the Novel: The Paradigm of Peter Weiss's". Red Letters. 16: 12–25.

- ^ Beise, Arnd; Birkmeyer, Jens; Hofmann, Michael (2008). Diese bebende, zähe, kühne Hoffnung: 25 Jahre Peter Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (in German). Röhrig Universitätsverlag. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-86110-438-4.

- ^ "Harun Farocki: On Display: Peter Weiss A Production Dossier" (PDF). Harun Farocki Institut. Berlin. November 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- ^ Bergh, Magnus (2003). "Die Kristallle von Peter Weiss". Peter Weiss Jahrbuch (Für Literatur, Kunst und Politik im 20. Und 21. Jahrhundert) (in German). 12. Röhrig Universitätsverlag: 29. ISBN 9783861103509. ISSN 1438-8855. OCLC 645781011.

- ^ Arakelian, Avo; Fischer-Defoy, Christine (1984). Spuren der Ästhetik des Widerstands: Berliner Kunststudenten im Widerstand 1933-1945 : eine Ausstellung des Forschungsprojekts "Geschichte der HdK-Vorgängerinstitutionen 1930-1945" (in German). Pressestelle der Hochschule der Künste. OCLC 1195741573.

- ^ Kunze, Max (1987). "Wirkungen des Pergamonaltars auf Kunst und Literatur". Forschungen und Berichte (in German). 26. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin -- Preußischer Kulturbesitz: 57–74. doi:10.2307/3881004. JSTOR 3881004.

- ^ Tarasti, Eero (31 August 2015). Sein und Schein: Explorations in Existential Semiotics. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-5015-0116-6.

- ^ Wannemacher, Klaus (2012). "Was aber bedeutet es, wenn Herakles nicht der große Menschheitsbefreier ist? Tendenzen der Romanadaption im postdramatischen Theaterfeld am Beispiel der Essener Bühnenfassung der Ästhetik des Widerstands". In Beise, Arnd; Hoffman, Michael (eds.). Peter Weiss Jahrbuch für Literatur, Kunst und Politik im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert. Band 21 (2012) (in German). Vol. 21. St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 63–92, 83–85. ISBN 9783861105282.

- ^ Wannemacher, Klaus (2012). "Was aber bedeutet es, wenn Herakles nicht der große Menschheitsbefreier ist? Tendenzen der Romanadaption im postdramatischen Theaterfeld am Beispiel der Essener Bühnenfassung der Ästhetik des Widerstands". In Beise, Arnd; Hoffman, Michael (eds.). Peter Weiss Jahrbuch für Literatur, Kunst und Politik im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert. Band 21 (2012). St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 63–92, 83–85. ISBN 978-3861105282.

- ^ Wannemacher, Klaus (2012). "Was aber bedeutet es, wenn Herakles nicht der große Menschheitsbefreier ist?". In Beise, Arnd; Hoffman, Michael (eds.). Peter Weiss Jahrbuch für Literatur, Kunst und Politik im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert. Band 21 (2012). St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universitätsverlag. pp. 63–92. ISBN 978-3861105282.

For a critique, pp83–92

- ^ Robert Stadlober, Peter Fricke, Helga Fellerer, Ulrich Frank, Paul Herwig, Rüdiger Vogler, Michael Troger, Helmut Stange, Christian Friedel, Stephan Zinner, Katharina Schubert, Sabine Kastius, Susanne-Marie Wrage, Hanns Zischler, Jochen Striebeck, Wolfgang Hinze, Jule Ronstedt (2007). Die Ästhetik des Widerstands : Hörspiel (Stage Play) (in German). Der Hörverlag. ISBN 9783867170147. OCLC 1080919830.

Directed and adapted by Karl Bruckmaier.

- ^ a b Olbert, Frank (17 February 2007). "Des Autors Wunschbiographie". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Archive. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ "PASSAGE". Theater Gegendruck (in German). Bochum. 30 September 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "VidaExtra, de Ramiro Ledo". Fundación MARCO (in Spanish). Servizo de Fundacións da Xunta de Galicia. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ "Interview: Rome - September 2011". Reclections of Darkness. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Grubbs, David (19 December 2016). "Hörspiel Pool - Weiss, Die Ästhetik des Widerstands". BR (in German). Munich. Retrieved 14 February 2022.