Talk:War of 1812/Archive 6

| This page is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

I think it's very much US POV - America did this, America felt this etc. No mention of Canada wanting to defend themselves, or of the fact that many Americans thought the war was unjustified. Can we get someone froma neutral country to write it, may be from Switzerland? :-) Deathlibrarian 21:48, 6 February 2007 (UTC)

- It would be absurd and totally inappropriate to use an identifiably Canadian pov for this article as CANADA DID NOT EXIST AS A STATE. Note that there is as much BRITISH pov in the article as US. This is a natural consequence of the fact that the British empire (not Canada) was in fact the state the US declared war on.

- More importantly, please take a quick look at the French and Indian War article. Do you see Any US posters pissing and moaning about the lack of a US pov on that war? And yet while canadians get constant mention in this article there are only references to "british colonists" in the French and Indian War article. Oh no! woe is us poor americans! nobody is presenting our unique US perspective on the french and indian war and instead we must be lumped together with the apron-string clinging canucks! horrors! ;)Zebulin 22:57, 6 February 2007 (UTC)

Canada did exist as a colony...whether you live in the "colony" of Canada, or the country of "Canada" if your country is being invaded you would be equally as unhappy(presumably). As much British POV as American??? You serious? Have you read this article?

As for the French and Indian War article, I can't see how that is relevant. If you have a problem with it being biased or badly written, go over there and re write it....its Wikipedia after all. Thats no reason for this article to be badly written or biased as well.Deathlibrarian 23:25, 6 February 2007 (UTC)

- I invite you to point out the most egregious examples of US pov in the article.Zebulin 23:29, 6 February 2007 (UTC)

The Brits saw the US attack on Canada as traitorous as at the time they "had their back turned" trying to fight Napoleon and remove him from occupying Europe. They were pissed big time about this. They also saw no problems in selling arms to the native americans, who were just trying to protect themselves from their lands being overun and being pushed onto disease ridden reservations....is that mentioned in the opening bit? Deathlibrarian 00:07, 7 February 2007 (UTC)

- lol, when they are that bad instead of posting them here in talk just do us all a favor and scrub them out straight away. I must have been asleep at my watchlist to have missed those. ;)Zebulin 00:38, 7 February 2007 (UTC)

No!..I am saying this is the British perspective and it *should be* included along with the US perspective that is already in there. Deathlibrarian 02:04, 7 February 2007 (UTC)

- ouch. I thought you were posting the most egregious examples of american pov. well hrmm. The way you phrase it isn't exaclty up to wiki standards IMHO. In any event can you cite any ref for the brits thinking the attacks were even remotely traitorous? that just doesnt make sense. The USA was not in any sense allied with the british empire let alone still thought of as a part of it by the British. How could *anything* it did in 1812 be seen as "traitorous"? Maybe this is just semantics you might mean they saw the attack as shamelessly opportunistic. Of course the Brits were in fact rather divided about the attack by the USA with regards to where the blame lay and to whether it was completely unprovoked. Hardly a case worthy of the generalization that "they were pissed big time" about it. The brits were also divided about selling arms to the natives. What they were not divided about was the importance of not allowing that opportunistic attack to harm the international standing of the empire by weakening it's image.

- I think one reason you might find less description of British POV in the article is that it seems to have been harder to pin down. The war had a drastically less jingo-charged effect on them and fewer broad generalized sentiments relating to the war emerged there than in north america. Having said all that, I think descriptions of british attitudes during the war certainly have a place in the article so long as they are either cited or at least nuanced enough to not over generalize british attitudes.

- Zebulin 04:42, 7 February 2007 (UTC)

Yes, traitorous is the wrong word, opportunistic and somewhat sneaky is more correct. I've been trying to find the reference, I read it a while ago online but can't find it. The Brits were well pissed off about being attacked by the US while they were struggling with Napoleon. Certainly UK Hansard would describe attitudes but I don't have access to it. Yes, and good point British attitudes to the war are certainly less prevalent, and there are few books written by Brits on the war of 1812.However, once I find some I will post, at the moment the US viewpoint overshadows this article (coming from my perspective as an Aussie!) Deathlibrarian 05:26, 7 February 2007 (UTC)

- Have you read or paged through Winston Churchills "A History of the English-Speaking Peoples"? That's at least one case of a british author examining the war. If you are looking for period primary source material regarding prevalent attitudes towards the war in Britain your hunt may be far more difficult and prone to selection bias as some publishers in britain during the war gave remarkably different perspectives on it than other contemporary british sources. They were indeed divided on (and not terribly pre-occupied with) the conflict. Don't hesitate to contribute anything you find however. We can try to fill in gaps for a more nuanced view later.Zebulin 05:47, 7 February 2007 (UTC)

British claim this as a victory?

I noticed that someone has changed the result to no victory, or made reference to the treaty of Ghent...but as far as I'm aware, the British at the time claimed this as a victory. I can't find anything online, but does anyone know? If so it should be noted in the article. Access to British Papers from the time or British Hansard should do the trick. Deathlibrarian 02:18, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- I agree with you that many Brits do see the war as a victory, although i haven't got any sources, the British where attacked by the Americans, who in reality just wanted Canada, the British succeded to maintaining the statas quo, and giving the Americans a severe bloody nose at a time when Britain was already fighting France, Spain (on and off), Holland (on and off) and Danemark, not to mention many smaller states. --Boris 1991 15:46, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- bloody nose at the Battle of new orleans, say? The Brits made a terrible blunder in getting into a war they did not need. Rather bad diplomacy one muct say, and a good reason to forget it, which they have. Rjensen 16:18, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

Isn't it funny that whenever anyone mentions the possibility of a British Victory to the War overall that an american will instantly turn around and mention New Orleans - despite it being fought after the war had ended, lost by troops who had never seen action before, led by a man desperately trying to equal his brother-in-laws greatness, and served no real purpose or outcome other than to lead the american people in believing their badly fought war of aggression was worth it. [Pagren]

- There are no references to show that the US really just wanted Canada. It is interesting how quick so many commentators here are to brush under the rug all other grievances officially declared and much discussed in the lead in to the war by the Americans involved in the decision to declare war.Zebulin 20:37, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- Deathlibrarian, this has been brought up a million times, and the result has always been the same. The way it is written now is very fair. There is no way that a British/Canadian victory will become the accepted version. My suggestion - do some research on Canada and document some more of its history. It might be more fulfilling to actually write articles than to fight an endless losing battle over a line in an infobox. Haber 21:27, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- The US obtained: end to impressment, end to trade restriction re France, end of arming the Indians, and the US destroyed the power of the Indians in both Midwest and South. And demolished an elite British army in the biggest and last battle. Best of all US won a sense of final independence -- no more British invasions to worry about. Seems a pretty good package for USA. Rjensen 21:36, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

(1) The US did not obtain an end to impressment, the UK order of council about impresement was dropped before the war began.And the Brits refused to sign away their right to impress Seaman in the Treaty of Ghent. (2) The British Army was not demolished, after New Orleans in fact it was sitting in Mobile, unchallenged by any American Army, and was preparing to take Mobile, but left when it heard the Treaty of Ghent had been signed. (3) The last battle of 1812 was not New Orleans, it was actually a victory for the British, Battle_of_Fort_Bowyer (4) Worst of all for the USA, the failed annexation of Canada united Canada and made them wary of the US. If the US hadn't of invaded Canada and united an otherwise divided country, parts of Canada probably would of naturally joined the US anyway. The war of 1812 wasn't the war that formed the US as a Nation, it twas the war that formed Canada as a Nation. As for the percieved no more invasions to worry about...have you ever thought that the Canadians felt the same way about the US after the war of 1812????? 211.28.212.25 15:08, 11 February 2007 (UTC)

- I don't think it's fair to say that the US achieved all of it's goals. The strongest statement that could be made is that the US had all of it's *declared* war aims fullfilled (some before war was even declared!). The accusation that at least one of the real though undeclared US goals of the war was to drive the British Empire out of Canada cannot be seriously challenged IMHO.Zebulin 22:31, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- that's an old Canadian myth that no longer is believed by experts. Rjensen 22:34, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- so the experts used to believe it? such a change in established consensus would presumably be well doccumented. Can you cite a reference for this current understanding that the US did not intend to drive the british empire out of north america?Zebulin 22:50, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- Gladly: [x Origins war 1812 article]: The idea that one cause of the war was American expansionism or desire for Canadian land was much discussed among historians before 1940, but is rarely cited by experts any more.[1] Some Canadian historians propounded the notion in the early 20th century, and it survives in Canadian mythology.[2] Madison and his advisors believed that conquest of Canada would be easy and that economic coercion would force the British to come to terms by cutting off the food supply for their West Indies colonies. Furthermore, possession of Canada would be a valuable bargaining chip. Frontiersmen demanded the seizure of Canada not because they wanted the land (they had plenty), but because the British were thought to be arming the Indians and thereby blocking settlement of the west. [3] As Horsman concludes, "The idea of conquering Canada had been present since at least 1807 as a means of forcing England to change her policy at sea. The conquest of Canada was primarily a means of waging war, not a reason for starting it."[4] Hickey flatly states, "The desire to annex Canada did not bring on the war." [5] Brown (1964) concludes, "The purpose of the Canadian expedition was to serve negotiation not to annex Canada."[6] Burt, a leading Canadian scholar, agrees completely, noting that Foster, the British minister to Washington, also rejected the argument that annexation of Canada was a war goal. [7] [endquote] Rjensen 22:56, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

- ^ Hacker (1924); Pratt (1925). Goodman (1941) refuted the idea and even Pratt gave it up. Pratt (1955)

- ^ W. Arthur Bowler, "Propaganda in Upper Canada in the War of 1812," American Review of Canadian Studies (1988) 28:11-32; C.P. Stacey, "The War of 1812 in Canadian History" in Morris Zaslow and Wesley B. Turner, eds. The Defended Border: Upper Canada and the War of 1812 (Toronto, 1964)

- ^ Stagg (1983)

- ^ Horsman (1962) p. 267

- ^ Hickey (1990) p. 72.

- ^ Brown p. 128.

- ^ Burt (1940) pp 305-10.

- even if this fails to convince anybody that the US had no desire to drive the british out of North America I nonetheless expect this fine referencing effort will help keep a lid on the accusations that annexing Canada was the primary US goal of the war. It bears repeating until such accusers finally begin to understand the situationZebulin 23:24, 9 February 2007 (UTC)

My research, rather than dealing with American authors revising the war, how about some primary source quotes? Jefferson: "The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighbourhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us experience for the attack of Halifax the next and the final expulsion of England from the American continent." John Randolph "Agrarian greed not maritime right urges this war. We have heard but one word - like the whipporwill's one monotonous tone: Canada! Canada! Canada!" My problem is that most of your references are American. I'm trying to find what some British Historians say about the War of 1812...unfortunatley, so far, without much luck. As for the frontiersman having "plenty of land"...if that was the case, why did they have that nasty habit of killing Native Americans so they could get theirs???. From my reading, the Native Americans used to put soil in the mouths of the Americans they killed because the Indians saw them as so intent on obtaining more land (got that from a Canadian website, but I assume its true???). If the US was so keen to take land from the Spanish and the Mexicans, I can't really see why they would not want Canadian land when they saw the opportunity. Oh and I'm thinking of writing an article on US bias on the war of 1812, the level of bias and the rewriting of history is almost as interesting as the war of 1812 itself. Deathlibrarian 02:44, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

- The Treaty of Paris of 1783: The British award the Americans all lands west of the Mississippi and South of the Lakes. Signed by George iii himself. The Indians under Tecumseh & his brother the Prophet began an anti-white revival religious movement to destroy all whites (and get arms from the British). That had to stop. Rjensen 03:04, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

Bad tecumseh for wanting the Indians to defend their own sovereign state.How dare he!211.28.212.25 08:18, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

- I don't think Rjensen was so much personally passing judgment on Tecumsehs actions as describing how those actions constituted causa belli with respect to the US and the british empire due to the military support tecumseh received from the British empire. At the very least it could be recognized as deeply hypocritical and provocative for the british empire to trade with Tecumseh who was at war with the US while preventing the US from trading with europe ostenably due to the british empires right to block trade with it's enemies.Zebulin 16:55, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

I think the threat from one American Indian Chief to the US was somehow probably not as great as the threat that Napoleon Bonaparte, the Army of France and its allies posed to Europe. Tecumseh was just trying to survive, not conquer the hold of the US. The Native Americans had already lost a lot of their land and were losing more. 203.35.150.226 07:42, 20 February 2007 (UTC)

- nonsense. How was nappy going to attack britain? balloons? By the time the war of 1812 was looming Brits were far less threatened by napolean than US citizens in the west were threatened by Tecumsehs war against the US. It's absurd to suggest that selling arms to Tecumseh while he was at war with the US government was non provocative while selling foodstuffs to continental europe was somehow unacceptable.Zebulin 08:22, 20 February 2007 (UTC)

- funny that you should mention the Mexican war. The US decisively defeated the entire Mexican military in that war and effectively ended all armed mexican resistance. And yet they didn't annex the economically largest areas of Mexico. There was nothing to stop them from annexing all of mexico except their desire to avoid having a large hostile population to govern. If all Americans wanted was land and as much as they could militarily take how do you explain their decision to not simply conquer and annex mexico outright instead of settling for the thinly populated outlying territories? The obvious problem with any proposed annexation of Canada is that unlike Mexico all of the most densely populated portions of Canada lay between the US and the thinly populated portions of Canada. It would not have been possible to annex any significant portion of Canada without being forced to attempt to govern a large hostile population.Zebulin 03:53, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

The obvious difference between Mexico and Canada was that the US presumably knew the Mexican people would be hostile, however Jefferson and many of the Americans thought the Canadian people would welcome the US annexation. They had good reason, the French Quebecois had revolted recently, and there were a whole bunch of US immigrants in Canada that they assumed would welcome the US. Jefferson: "The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighbourhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching". In fact most of the Canadian were pretty pissed off when the US invaded. Burning towns to the ground and leaving people to freeze probably isn't the best PR once could do. In fact, many native Americans sided with the British. Deathlibrarian 08:21, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

"The Brits made a terrible blunder in getting into a war they did not need. Rather bad diplomacy one muct say, and a good reason to forget it, which they have."

Well well, lets get our facts straight... AMERICA declared war, not Britain; they didn't get themselves into a war at all, the yankees dragged them into one. If you actually look at the war, you'll see that AMERICA made the terrible blunder.

And by the way, for all you Americans who think you won the last land battle of the war, you didn't... The British captured for boyer just around a month after New Orleans.

Jefferson's hatred of Britain and Europe

Jefferson was long out of office in 1812 and did not shape national policy, But he did have an interesting viewpoint: he wanted to purge the New World of British corrpution. Biographer Merrill Peterson pp 932-33 explains:

- "War, on the one hand, would cut out the lingering cancer of British influence: "the second weaning from British principles, British attachments, British manners and manufactures will be salutary, and will form an epoch of the spirit of nationalism and of consequent prosperity, which would never have resulted from a continued subordination to the interests and influence of England." The American strategy, obviously, was to attack Canada and drive Britain from the continent. "The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching," Jefferson boasted. Halifax would fall in the next campaign. The Floridas, too, would become an object. The world would then see such an "empire of liberty" as had never been surveyed since the creation. This conception of the war as an epoch of liberty and nationality had firm roots in Jefferson's thought. It was a war against Britain, of course, but in the larger sense it was against Europe, the Old World, and in this sense it promised the consummation of that hemispheric "American system" toward which New World ideology had aimed from the beginning. "What in short is the whole system of Europe towards America but an atrocious and insulting tyranny," Jefferson wrote to one of his unknown correspondents. "One hemisphere of the earth, separated from the other by wide seas on both sides, having a different system of interests flowing from different climates, different soils, different productions, different modes of existence, and its own local relations and duties, is made subservient to all the petty interests of the other, to their laws, their regulations, their passions and wars, and interdicted from social intercourse, from the interchange of mutual duties and comforts with their neighbors, enjoined on all men by the laws of nature." A war commenced under such favorable auspices as he believed this one to be, holding the promise of so much gain in liberty and dignity and independence, he had almost come to think a blessing to the nation."[ end Peterson quote] -- and a blessing for Canada to to be rid of its horrible King George III (he was still around). Rjensen 04:03, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

- not entirely a Canadian myth then eh?Zebulin 04:31, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

- Yes, a Canadian myth invented after the war....called the "militia myth". Jefferson certainly hated the Brits and wanted them gone--but he had been out of office for years and wrote private letters to friends that were not published till years later. Rjensen 14:17, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

- The land grab story is Canadian mythology designed to bolster Canadian nationalism and induce anti-American sentiments, and has been rejected by scholars for many decades. The states that would supposedly benefit (like New England and New York) opposed the war, while the states that were far away, like Kentucky, Virginia and South Carolina, were strong supporters. Rjensen 03:33, 23 March 2007 (UTC)

- not entirely a Canadian myth then eh?Zebulin 04:31, 12 February 2007 (UTC)

- Nothing like setting up a straw man in order to knock it down. What Canadians actually believe is that the United States wanted to expel the British authorities from North America and thus the Canadian colonies would join the United States as new and separate states. Which is not the same as the United States looking to conquer and rule over the British colonies as United States colonies. Even this "benefit", i.e. that of becoming free and independent citizens of the United States was not considered desireable by the majority. The colonists preferred colonialism and British identity to independence and US citizenship. Dabbler 11:04, 23 March 2007 (UTC)

- well, no. "desireable by the majority" = talking like a Yankee. Anybody with democratic notions like that would be in trouble in Canada. Rjensen 11:14, 23 March 2007 (UTC)

- Rjensen, your prejudices and apparent ignorance about Canadian colonial history and government have been excessively displayed here. Believe it or not, most Canadian colonists did prefer British colonial rule over joining the United States and although the Family Compact ruled the roost in Upper Canada for a while it wasn't the absolute despotism that you seem to believe it was. It also did evolve and the notion of joining the US never became desirable to the majority.

- well arrogance is not very Canadian. Nor in 1812 was democracy. The American goal of ridding the continent of british influence was finally achieved--I note that the Canadians recently refused to allow the Prince of Wales to visit.Rjensen 22:10, 24 March 2007 (UTC)

- That seems like saying Iran would rid Eurasia of US influence if it should refuse permission for an American to visit Iran. The british continued to have substantial influence in all American and certainly north American affairs until at least well into the 20th century. I would say this influence was especially decisive during the US civil war where it strongly effected the policies of both the confederate and the Union governments. What on earth do you mean when you claim that the war of 1812 somehow rid the continent of british influence?Zebulin 22:27, 24 March 2007 (UTC)

- I'd say the Royal family is more popular in US than in Canada these days. The history of Canada in 20th century is a history of revolt against Britain (starting with the Alaska boundary dispute of 1903, followed by French revolt in 1917-18, rejection of Byng 1926, alliance with US in ww2, popular culture shift toward Hollywood after ww2, rejection of Union Jack flag). In that sense the Americans won their long-term goal, though it took a while for phlegmatic Canadians to realize they had become much more American than Brit. Rjensen 22:39, 24 March 2007 (UTC)

- well, no. "desireable by the majority" = talking like a Yankee. Anybody with democratic notions like that would be in trouble in Canada. Rjensen 11:14, 23 March 2007 (UTC)

OK, I've been watching this discussion with some amusement, but the preceding is a bit much. 20th century revolt against Britain? Why would Canadians need to, since Canada was an independent Dominion internally since 1867 and externally after the 1933 Statute of Westminster. To look at particular statements:

- The Canadian government was po'ed at the British, whom they viewed as siding with the Americans during the Alaska boundary dispute.

- The "French revolt" is called the conscription crisis in Canada. It was a result of many francophone Canadiens being opposed to the Canadian (not British) government's introduction of a military draft. Many anglophone Canadians viewed conscription as a rotten idea, too.

- The King-Byng affair was a constitutional crisis at least partly precipitated by Lord Byng (and arguably partly by Mackenzie King). The individual more than his nationality was not appreciated. Canada still has a vice-regal (but, following the post-Byng tradition, apolitical) Governor-General.

- Alliance with the US in WW II? Well, yes, once the US finally joined in. Canada declared war on Germany independently of, and 4 days later than, the UK, in Sept., 1939 - as allies of the UK (and Aussies, Kiwis, Indians, South Africans, French, Poles, Czechs, Belgians, Dutch, Danes, Norwegians, ...). Many US citizens joined the Canadian Forces, joining us in the fight for democracy when their own country was officially neutral (as many had in 1914-1917). After Pearl Harbor, America finally (2 years and two months later) became allied with us!

- The popular culture shift is true, to a disturbing extent for some Canadians. But then again, the popularity of Hollywood over domestic productions has also been a source of national angst (for some) in other countries, including France and the UK. Hardly a "rebellion" against the UK.

- Rejection of the Union Jack? I may be mistaken, but I do believe that the Union Jack is still an official flag in Canada, and features prominently in the provincial flags of Newfoundland, Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia. Oh, and I also believe it's found in the state flag of Hawaii - part of a nation that "rejected" the British; also (historically) in the colours chosen for the American national flag. And certainly while the "Maple Leaf Rag" (meant humourously and with affection - and with apologies to American songwriter Scott Joplin) doesn't resemble the Union Jack, neither does it remotely resemble the Stars-and-Stripes.

WHEW! Now that that's over, could we please continue with matters germane to this article - the causes and outcomes of the War of 1812? Just my 2.5¢¢ worth. Esseh 23:40, 2 April 2007 (UTC)

- If that statement reflects a genuine trend I would suggest that the war 1812 at best had no effect on that trend and in all likelihood at least temporarily actually retarded or even reversed that trend.Zebulin 00:40, 25 March 2007 (UTC)

- I agree with Driftwoodzebulin -- the war allowed reactionary forces in Canada to repress democracy for a couple decades, and gave a boost to imperial-oriented Anglicans. Rjensen 03:37, 25 March 2007 (UTC)

- If that statement reflects a genuine trend I would suggest that the war 1812 at best had no effect on that trend and in all likelihood at least temporarily actually retarded or even reversed that trend.Zebulin 00:40, 25 March 2007 (UTC)

Moved this from article

The British and United Empire Loyalists elite, rejecting democracy and republicanism, tried to set Canadians on a different course from that of their former enemy.

This was placed as an intro to the sentences about the militia myth, implying that the British and the Loyalists created the myth on purpose as a way of "setting Canadians on a different course" (whatever that means). Since that assertion is not present in the online source given, I am moving it here. --Anonymous44 01:42, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- the sentence is accurate enough and does not mention or imply anything. Rjensen 01:51, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- Please stay cool. IMO, it does imply it. And I now notice that on the Origins of the War of 1812 talk you yourself have expressed exactly what I'm saying it implies. That's fine with me, but you know, it should be sourced before it's in the article. --Anonymous44 01:58, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- I added a source (Kaufman) that makes the point explicitly. Rjensen 02:01, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- Sorry, could you help me a little and tell me precisely where he is making it? I can see where he is saying that 1812 was vital for Canadian identity, but that's another thing. --Anonymous44 02:12, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- I added a source (Kaufman) that makes the point explicitly. Rjensen 02:01, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- It's a paraphrase. What statement do you think is false? Rjensen 02:52, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- I'm not saying it's false, I'd just like to make sure it is sourced (and of course, there's a difference between the "scholar X says that" kind of sourcedness and the "it is an established truth that" kind of sourcedness). The statement is that "The British and United Empire Loyalists elite ... sponsored ... the (militia) myth", and that they did it in order to set Canada on an undemocratic and non-republican course (by boosting Canadian national pride). I think it's clear that this statement sounds a little controversial, being one step away from saying that the entire Canadian identity is a hoax created by the enemies of democracy. --Anonymous44 03:09, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- Please stay cool. IMO, it does imply it. And I now notice that on the Origins of the War of 1812 talk you yourself have expressed exactly what I'm saying it implies. That's fine with me, but you know, it should be sourced before it's in the article. --Anonymous44 01:58, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

- most Canadian historians agree that the British-oriented folks had been worried before 1812 that so many American settlers spelled trouble. Historians I think agree that the pro-Brit forces gained huge momentum after the war, that they created the militia myth, and that they repressed republicanism and democracy, which they identified with the USA. That's pretty standard, is it not? For example we have studies showing the Anglicans became pretty aggressive after 1815 and overwhelmed the Methodists. there's no "hoax" here but the establishment did now want any democracy or democrats. For example, this article: George Sheppard, : "Deeds Speak": Militiamen, Medals, and the Invented Traditions of 1812." in Ontario History 1990 83 #3 pp 207-232. Abstract: "Deeds Speak" was the motto of the Upper Canadian Militia. This article describes the activities of the militia during the War of 1812. The accounts of the Reverend John Strachan are one of the sources of the "militia myth," extolling the bravery and importance of the militia. In fact, the deeds of the Upper Canadian militia included wholesale desertion and a refusal by many men, particularly in York, to volunteer at all. A few genuine heroes were nominated to receive medals, but they were never distributed. The leaders of York nominated several hundred militiamen for medals, even though many had never fought in a battle, resulting in a controversy that lasted almost 30 years. Rjensen 21:40, 3 April 2007 (UTC)

Brief comment. Republicanism ≠ Democracy. Republicanism is merely one form of democracy. Hence, it is possible to be a democracy without being a republic. And indeed, the UK, Canada and much of the Commonwealth are Constitutional Monarchies - also democracies, but not republics. See also People's Republics, which tend to be non-democratic, whether republics or not, and ruled by autocrats (Monarchs, essentially, though maybe termed President-for-life) or oligarchies. Thus, discouraging republicanism need not necessarily mean suppressing democracy. Esseh 00:28, 4 April 2007 (UTC)

- Answer to Jensen. To be brief - it's perfectly possible that what you're saying is indeed "pretty standard", but if it is, why not source it? The quote you're giving does not make the questioned claim either (as far as I can see, it only says that the miltia myth was a myth, which is not the subject of our dispute).

- Now, I am not *that* very interested in American history (not as much as to follow articles and collect dozens of books about it), so I am in no position to say what the current scholarly consensus is (if there is any). But I am concerned that the statement might be anti-Canadian POV/OR (similar to the questioning of Macedonia's origin/identity by my own Bulgarian compatriots). My understanding is that yes, sure, the US was associated with more democracy, and Canada with less of it (especially in view of the loyalist yankee origins of most Anglo-Canadians). This is true, even though a partly democratic form of government (comparable, though somewhat more restricted than the one in the "US" prior to the Revolution) was present in Canada (elected assemblies + British-appointed governor). So yes, "less democracy" was somehow connected to Canadian patriotism, and Canadian patriotism was somehow connected to the creation of the militia myth. This does not automatically mean that the striving for "less democracy" was the principal cause behind Canadian patriotism or the militia myth. And it doesn't mean, going one step further, that any democratically minded Canadian in 1812 wanted the US to conquer Canada, while any Canadian opposed to US conquest or proud of British-Canadian military successes was a reactionary. I might be wrong, but to me, this seems like extreme pro-US POV. --Anonymous44 11:48, 4 April 2007 (UTC)

- No this is what scholars found. The pro-Empire people were opposed to democracy and republicanism which they identified with USA, with American immigrants, and with American ideas. So they opposed it vigorously and prevented democracy in Canada for decades. Of course Canada has changed and now is democratic. But not then. So what's the POV part???? Are there historians who disagree? if so please cite them. Here are some quotes from Donald Creighton's famous history of Canada re post 1812 (pp 217ff): in Upper Canada, The governing class, attacked by the Reformers as 'The Family Compact,' was a group of judges, civil servants, bankers, merchants, and Church of England clergymen, a number of them related, and more English than the English in their devotion to the old order. The Anglicans bitterly fought the Americans (which had strong American links), "the Methodists represented the growing nationalism of the Canadian frontier, just as they represented its restless democracy in their resentment at the privileges and claims of the English church." ... "In Upper Canada, the attempt of the Loyalists and the Anglican clergy to impose their cultural standards on the community was resisted... strenuously" Again on pp 233-34 regarding 1830s: "In the [Upper and Lower] Canadas, a large group of people was clearly dissatisfied with the slow pace of reform and resentful of the abuses and inequalities which still remained. ... Their crusade was the crusade of the common man against the powerful individual and the great corporation -- the crusade ... which was sweeping the western American states and had triumphed in the election of Andrew Jackson to the presidency. The Upper Canadian radicals hated the Church of England and its close relations to the state, its efforts to control education, and its exclusive claims to the Clergy Reserves. They were furious that humble township schools should be neglected, while the district grammar schools were well equipped ... . To them such corporations as the Bank of Upper Canada and the Welland Canal Company were 'abominable engines of state' which corrupted government and oppressed the people. They hated the whole land-granting policy of Upper Canada....In the opinion of the radicals, the whole system of privilege and abuse was held together in its own interest by a little oligarchy of appointed executive and legislative councillors at Toronto called the 'Family Compact,' and by the network of little local family compacts, composed of appointed justices of the peace who governed the countryside." So there was democratic revolt brewing in 1830s! Rjensen 21:30, 4 April 2007 (UTC)

Oh course there were malcontents in the Canadas. This came to a head in the Rebellions of 1837. However, neither revolt received widespread support, and failed miserably. The Canadian people were interested in democracy; they just didn't want American democracy. And even in your quote, all of the above was "in the opinion of the radicals", and thus not necessarily the prevailing view.

04:16, 5 April 2007 (UTC)Esseh

- This is all completely beside the point. Of course there were political conflicts in the 1830's (and, to some degree, earlier). This does not mean that national resistance to a US invasion in the 1810's was connected to being undemocratic, or vice versa; in particular, it doesn't mean that the militia myth was created by the "undemocratic" forces specifically with the purpose of fighting democracy. That might be your conclusion, but if it's only yours, that would be OR. So please cite a scholar who says that. It would be even better if you can cite a scholar who says that this is the predominant opinion among scholars (as you say it is).

- "The Anglicans bitterly fought the Americans (which had strong American links)" - judging from Kaufman's exposition, almost everybody involved (apart from later English and Scottish emigrees) was (ex-)"American", and (ex-)loyalist, having fled from the Revolution. So, regarless of their differences concerning the degree of self-government and liberalism, most Canadians would have their roots in a tradition of opposition to the US. "Anglican" is a religion, not an ehnicity, so it can't be the opposite of American. --Anonymous44 11:40, 5 April 2007 (UTC)

Thanks, Anonymous44. I agree with you, believe it or not. I feel this article is somewhat biased toward the American POV; I haven't edited anything yet, but have been trying to contribute to the discussion (see my, mostly unanswered, posts above) to reach some consensus as to how it could be revised.

You are correct: there were internal political conflicts in the 1830's (and before, and after, and still today). Indeed, my problem is that this internal dissention is being portrayed as strictly a Canadian problem. Americans also had their internal dissention in 1812, as well as before and after (New England opposed the war; problems with the wealthy trying to maintain their position and denying universal suffrage in the US, etc...). You are also correct that "Anglican" is a religion, not an ethnicity, and it's called "Episcopalian" in the US to this day. Since many Americans were, and are Episcopalian, it's unlikely that there was an "Anglican" conspiracy at any time. A ruling-class conspiracy? Likely; but that would not be unlike the conspiracies of ruling classes to maintain their positions everywhere (including 1812 America).

I would disagree with you on the point that most Canadians in 1812 were ex-American and ex-Loyalist. In fact, I think the majority of the population would have been francophone Canadien, though I don't know where to look for census figures. It is largely irrelevant, though, since the attempted invasion of 1812 had the ultimate effect (in my mind) of unifying Canadians in their desire not to be Americans, rather than (perversely) in their desires to be any one thing. Does that make any sense? Esseh 02:18, 6 April 2007 (UTC)

- I, too, think the French-speaking part was larger, I just didn't take it into account at all (I am under the impression that they mostly lived a separate life all along - the militia myth and the emerging Canadian patriotism in general didn't concern them so much as the anglophones, and the political struggles were of a different nature, too). BTW, I don't know about the whole article being biased; I have only been disputing one single sentence (incredible as it may seem, given the length of the discussion), which I think is unsourced and US POV. I have some doubts about another issue (the "expansionism for land" thing, see previous discussions), but I would need to look into more sources if I am going to address that in the future. Don't really have time right now. --Anonymous44 15:21, 7 April 2007 (UTC)

Hi Anon44, and thanks. You're right in one sense, and wrong (IMHO) in another. The francophones did, by and large, live a separate life. But emerging Canadian patriotism did concern them, in a different way. In fact, at that time, the francophones were les Canadiens (neither French, no English, nor American!) in both their own minds, and to the English-speaking inhabitants, who (whether British-born or Loyalist) were largely "British" in their own minds. I don't think an English version of a "Canadian identity" appeared 'til much later - probably largely influenced by the events (and mythology) of the War of 1812. In 1812, as during the American Revolution, the Americans (I think) hoped for a mass revolt of the Canadiens (and les Acadiens) against the British to help them in their goals. The British, for their part, recognised this danger, and it is reflected in several provisions of the Quebec Act before the Revolution and in many of their later dealings with the francophones élite (especially the Catholic church) after. As for bias, I agree. The main problem is that one sentence, and in the reasons: territorial expansion was an unstated reason, I am convinced. But it was territorial expansion not into Upper and Lower Canada, so much as it was expansion into the Ohio valley (then part of Canada) and what is now Western Canada. However, the main "bias" is rather one of omission; the views and actions of the majority of those who would self-identify as "Canadians" (les Canadiens) is almost completely ignored. I have wanted to correct some of this, but given the heated discussion here, have so far refrained. As always, comments welcome. Esseh 02:02, 9 April 2007 (UTC)

- The Treaty of 1783 gave the Ohio Valley to the USA. British agreed to evacuate their forts in the Jay Treaty (1795) and did so, but kept supplying the Indians with guns and powder. Rjensen 02:25, 9 April 2007 (UTC)

Thanks Rjensen. My reading suggests the Jay Treaty settled precious little, and the exact area of the boundary remained in dispute, even in Eastern areas (see the Aroostook War and the Republic of Madawaska, and the Republic of Indian River) as well as Western (Northwest Angle). The Mississippi still remained navigable to both (per the Treaty of Paris), and de facto the western boundary of the U.S. Wherever the boundary was, it did not sit well with those Americans wishing to expand west. Interestingly, the Jay Treaty was vehemently opposed by Jefferson and others as a sell-out. Could this be an additional cause of the war? Jingoism is surely not merely a British affliction. Esseh 03:39, 9 April 2007 (UTC)

- The Jay treaty solved some but not all the boundary issues (it's a LONG boundary and went through mostly uninhabited woods.) Jefferson denounced the Jay treaty but when he became president in 1801 he followed its terms and kept the Federalist minister in London who was still negotiating $$$ issues (which were resolved) and boundaries. Jay produced 10 years of good will and profitable commerce, but ended in 1805 for reasons connected to France. Rjensen 03:46, 9 April 2007 (UTC)

- Yup; longest undefended in the world (though "Homeland Security" types on both sides may change that yet). Correct me if I'm mistaken, but though Jefferson did uphold the treaty once in office, he was largely the one that railed against the British in favour of an alliance with the French way before that. His views were known (including Canada being a "mere matter of marching"), and really, 10 years is not that long a time. Canada not for expansion (in terms of settlement), but welcome to join, if the British were driven out, but the West? Definitely an expansionist move. While on the topic of borders, I was really surprised that one major concession the U.S. did win from the War of 1812, namely the demilitarization of the Great Lakes, is never mentioned. One reason I ask is the recent push by the U.S. Coast Guard to seriously arm its patrol boats on the Lakes - ultimately a reversal of the terms it sought! Somewhat ironic, no? Esseh 08:09, 9 April 2007 (UTC)

Concerning the question whose patriotism was concerned by the war of 1812 - at least this text by Eric Kaufmann, which Rjensen was kind enough to point out to me, speaks exclusively of the emergence of an Upper Canadian (i.e. anglophone) identity.

Anyway - I now notice that the whole three-sentence paragraph has more faults, apart from the unsourcedness of the assertion that the loyalist elite "sponsored" the myth in order to combat democracy. First, it repeats the same thing about the militia myth and nationalism as the previous paragraph. Second, while there is no doubt that the Tory loyalist elite was opposed to the degree of democracy that was present in the US (although Kaufmann doesn't even say that, speaking instead of their desire for a "gradual change within the British system" rather than "rebellion"), none of the present sources says that this was a "consequence" of 1812, and the whole section is entitled "Consequences". Thus, the only remaining info that is both useful and sourced is the bit about Canada supposedly not needing a regular professional army. So I am incorporating that into the previous paragraph, and removing the rest for the time being. The Kaufmann link is very interesting and useful, so I'm keeping it as a source for the whole paragraph. --Anonymous44 12:02, 10 April 2007 (UTC)

War Of 1812

I'm a middle school student and I was asked by my tacher to do some trivia on the War of 1812. I have a question i'm stuck on mind helping. The question is Which famous ship was called "Old Ironside?" Why was it called this? Thanks

USS Constitution - called old iron sides because it was covered in sheets of Iron across the hull making cannon balls bounce off. Nice ship, but she's got nothing on HMS Victory ;o) [Pagren]

- Ironsides (USS Constitution) was all oak. no iron plating. it was *thick* oak though and cannon shot did bounce off the sides hence the name.Zebulin 17:14, 5 April 2007 (UTC)

guest User

Two Images

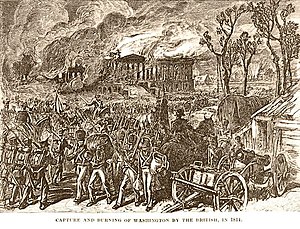

Look at the two images:

What do you think?The Anonymous One 01:25, 5 April 2007 (UTC)

Very nice. How is the image to the left relevant here? Esseh 18:25, 4 April 2007 (UTC)

You guess.The Anonymous One 00:50, 5 April 2007 (UTC)

OK, the left image is totally irrelevant to either the article or the discussion at hand. The left might go with the beginnings of the assault on Hong Kong and Singapore, or the bombing of Darwin in Oz, or perhaps 6-7 December, 1941. The one below could be paired with the burning of York, UC. Does that help? Esseh 01:49, 6 April 2007 (UTC)