Talk:Tutankhamun/Cause of Death

Investigations into the death of jKing Tutankhamun.

The cause of Tutankhamun's death was unclear, and was the root of much speculation. In early 2005 the results of a set of CT scans on the mummy were released.

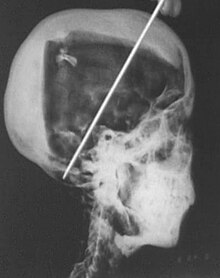

Since the tomb’s rediscovery in the early 1920s, the mummy has been X-rayed three times: first in 1968 by a group from the University of Liverpool led by Dr. R. G. Harrison, then in 1978 by a group from the University of Michigan, and finally in 2005 a team of Egyptian scientists led by Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, Dr. Zahi Hawass, who conducted a CT scan on the mummy. In 2010 another team conducted a DNA analysis on the remains of Tutankhamun and four of his relatives. ==1968 X-Rays, Discoveries and Conclusions(such as his broken leg) X-Ras of Tutankhamun’ X-rays of Tutankhamun's mummy, taken in 1968, revealed a dense spot at the lower back of the skull indicating (and interpreted as) a subdural hematoma. Such an injury could have been the result of an accident, but a trauma specialist from Long Island University thought this was highly unlikely because that part of a person’s head is usually not impacted in an accident. [1] [2][3] Scientists also discovered a small, loose, sliver of bone within the upper cranial cavity, which added to the speculation that Tutankhamun had died after sustaining a serious head injury. However, given the cement-like properties of the resin used to embalm Tutankhamun’s body, it is unlikely that if there was anything lose inside of Tutankhamun’s skull before it was embalmed, it would not still be loose after the process was completed. In fact, since Tutankhamun's brain was removed post mortem in the mummification process, and considerable quantities of now-hardened resin introduced ‘’into’’ the skull on at least two separate occasions after that, had the fragment resulted from a pre-mortem injury, some scholars, including the 2005 CT scan team, say it almost certainly would not still be loose in the cranial cavity. But other scientists suggested that the loose sliver of bone was loosened by the embalmers during mummification, but it had been broken before. A blow to the back of the head (from a fall or an actual blow) caused the brain to move forward, hitting the front of the skull, breaking small pieces of the bone right above the eyes.[2]

In February 2010, the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that the 19-year-old may well have died of complications from malaria, combined with a rare bone disorder affecting the foot called Kohler disease II, a disease typically affecting boys aged 5–9 caused when the navicular bone temporarily loses its blood supply. As a result, tissue in the bone dies and the bone collapses, producing symptoms of a club foot. He also had a curvature of the spine.

"Not long before his death, the king fractured his leg, and the scientists think this was important. The bone did not heal properly and began to die. This would have left the young king frail and susceptible to infection. What finished him off, they believe, was a bout of malaria on top of his general ill health."[4]

Theories as to who was responsible for the death include Tutankhamun's immediate successor Ay, his wife, and his chariot-driver.[3] Calcification within the supposed injury indicates that Tutankhamun lived for a fairly extensive period of time (on the order of several months) after the injury was inflicted.[3]

2005 findings[edit]

March 8, 2005, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass revealed the results of a CT scan performed on the pharaoh's mummy. The scan uncovered no evidence of a blow to the back of the head and no evidence suggesting foul play. There was a crack in the skull, but it appeared to have been the result of drilling by embalmers. A fracture to Tutankhamun's left thighbone was interpreted as evidence that the pharaoh badly broke his leg shortly before he died and his leg became severely infected. Members of the Egyptian-led research team recognized, as a less likely possibility, that the fracture was caused by the embalmers. All together, 1,700 images were produced of Tutankhamun's mummy during the 15-minute CT scan.

Much was learned about the young king's life. His age at death was estimated at nineteen years, based on physical developments that set upper and lower limits to his age. The king had been in general good health and there were no signs of any major infectious disease or malnutrition during his childhood. He was slight of build, and was roughly 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) tall. He had large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, although it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathological. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten (possibly his father, certainly a relative), often featured such an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality. The research also showed that the pharaoh had "a slightly cleft palate".[5] Scientists found a slight bend to his spine also, but agreed there was no associated evidence to suggest that it was pathological in nature, and that it was much more likely to have been caused by the embalming process. This ended speculation based on the previous X-rays that Tutankhamun had suffered from scoliosis. However, it was subsequently noted by Zahi Hawass that the mummy found in KV55, provisionally identified as Tutankhamun's father, exhibited several similarities to that of Tutankhamun — a cleft palate, a dolichocephalic skull and slight scoliosis (also found on one of Tutankamun's stillborn daughters), the first and third elements being a common defect on people suffering from Klippel-Feil syndrome[6][7] or Marfans syndrome,[8] which incapacitated him and might have played a role in his accidental death. The 2010 studies found no evidence of Marfans, so this theory is disproved. The large number of long sticks found in the tomb have been identified by some as walking sticks, aids required by his bone problems.

The extreme dolichocephaly was once thought to have been either the product of head binding or a family congenital deformity,[9] but these assumptions were also debunked by the study.[10]

The 2005 conclusion by a team of Egyptian scientists, based on the CT scan findings, is that Tutankhamun died of gangrene after breaking his leg. After consultations with Italian and Swiss experts, the Egyptian scientists found that the fracture in Tutankhamun's left leg most likely occurred only days before his death, which had then become gangrenous and led directly to his death. The fracture, in their opinion, was not sustained during the mummification process or as a result of some damage to the mummy as claimed by Howard Carter. The Egyptian scientists also have found no evidence that he had been struck on the head and no other indication that he was murdered, as had been speculated previously. Further investigation of the fracture led to the conclusion that it was severe, most likely caused by a fall from some height — possibly a chariot-riding accident due to the absence of pelvis injuries — and may have been fatal within hours[11]

Despite the relatively poor condition of the mummy, the Egyptian team found evidence that great care was take with the body of Tutankhamun during the embalming process. They found five distinct embalming materials, which were applied to the body at various stages of the mummification process. This counters previous assertions that the king’s body had been prepared in a hurry. In November 2006, at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America, Egyptian radiologists stated that CT images and scans of the king's mummy revealed Tutankhamun's height to be 5 feet 6 inches tall, a revision upward from earlier estimates.[12]

Tut could have died of a Contra-coup injury, in which he hit the front of his head, resulting in hemorrhaging. This would make it look like he was bludgeoned, but what most likely happened is that he fell off his chariot.[13]

The evidence that he died away from 'home' is that he had an excess of resin poured on him (more than usual), to hide the smell of decay. He also had flowers that only bloom in the spring wrapped around his neck. Since mummification takes about 3 to 4 months, he would have died in December or January, which is during the hunting season.[14] The hunting-accident explanation was given further force in a 2007 documentary film[15] which was shown on Australian national TV in October 2009.

The film reveals that a robbery during the Second World War damaged Tutankhamun’s mummy and obscured key evidence as to how he died. But now, evidence from CT scans and new research suggests that Tutankhamun was not murdered, but died from a broken leg caused during a hunting accident.[16]

These theories have been overturned by the DNA studies noted above, released in February 2010, which showed the king died of a combination of malaria and a bone disease. Also he died in chariot.

DNA study findings[edit]

A DNA study released in February 2010 claimed that Tutankhamun was weakened by congenital illnesses and died of complications from the broken leg aggravated by severe brain malaria.[17]

Genetic tests have provided evidence that Tutankhamun and at least four other mummies from his family were infected with Plasmodium falciparum, a parasite that causes an often deadly form of malaria. The team, led by Zahi Hawass, of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo, concluded that the king’s many disorders probably weakened his immune system, so that he could have died after suffering a “sudden leg fracture, possibly introduced by a fall,” which became life-threatening when he got malaria.[18]

The study also revealed that Tutankhamun suffered from a cleft palate, Köhler's disease and club foot.[17] Dr. Zahi Hawass and his team have now examined the remains of Tutankhamun and 10 other royal mummies from his family — two of which they have now confirmed using genetic fingerprinting to be the young king's grandmother and most probably his father. They say there is no compelling evidence to suggest King Tutankhamun or indeed any of his royal ancestors had Marfan's Syndrome.[19]

- ^ "King Tut Murder Mystery Solved by LIU Egyptologist Bob Brier". Long Island University. 1997-01-17.

- ^ a b King, Michael R. (2006-09-13). Who Killed King Tut?: Using Modern Forensics to Solve a 3300-Year-Old Mystery (With New Data on the Egyptian CT Scan). New Ed edition.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Brier, Bob (1999). The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story.

- ^ Roberts, Michelle (2010-02-16). "BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ^ Handwerk, Brian (March 8, 2005). "King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show". National Geographic News. p. 2. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- ^ Nefertiti and the Lost Dynasty, National Geographic Channel 2007

- ^ The Assassination of Tutankhamun, Discovery Channel, 2006

- ^ "h2g2 - Marfan Syndrome". BBC. 1978-01-02. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "A Feminine Physique, a Long, Thin Neck and Elongated Head Suggest Egyptian Pharoah Akhenaten Had Two Rare Disorders", University of Maryland Medical Center Press Release, May 2, 2008. http://www.umm.edu/news/releases/akhenaten_deformities.htm

- ^ "Tutankhamun's CT Scan". http://www.egyptologyonline.com/ct_scan_report.htm. Accessed 09-21-09. Retrieved 09-21-09.

- ^ Ian Sample (2006-10-28). "Boy king may have died in riding accident". London: The Guardian.

- ^ "Radiologists attempt to solve mystery of Tut's demise". 2006-10-26.

- ^ (Coplen, J. D. (n.d.). The Death of King Tutankhamun. Retrieved March 20, 2009, from The Tut Investigation: http://www.iois.net/TutInvestigation.htm).

- ^ (King Tut 'died from broken leg' . (2005, March 8). Retrieved March 21, 2009, from BBC News: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4328903.stm>

- ^ Tutankhamun: Secrets Of The Boy Kingdocumentary film

- ^ Tutankhamun: Secrets Of The Boy King ABC1 TV guide, 27 October 2009

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

assocwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Incest was true curse of Tutankhamun

- ^ Roberts, Michelle (2010-02-16). "'Malaria and weak bones' may have killed Tutankhamun". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-03-12.