Pacha (Inca mythology)

|

| Inca Empire |

|---|

| Inca society |

| Inca history |

This page's factual accuracy is disputed. (April 2024) |

The Quechua word pacha (Quechua pronunciation: [pætʃæ]) means ‘place, land, soil, time period’[1] in different contexts, and has been attributed as encoding an Inca concept for dividing the different spheres of the cosmos in Inca mythology akin to 'realm' or 'reality'. This latter interpretation, though, is disputed since such realm names may have been product of missionaries' lexical innovation (and, thus, of Christian influence).

The word pacha in Quechua languages[edit]

In contemporary Quechua languages, pacha means ‘place, land, soil, region, time period’.[1][2][3] The use of the word for both spatial and temporal reference has been reconstructed, with the same meanings, to Proto-Quechuan *pacha.[4][5] On the contrary, there would be no etymological relation of such word with Proto-Quechua *paʈʂak ‘one hundred’,[4] or *paʈʂa ‘belly’,[6] nor with Southern Quechua p'acha ‘clothes’[1].[7] Whether the word is being used for spatial or time reference is pretty clear according to context, as in pacha chaka ‘earth bridge’[2] or in ⟨ñaupa pacha⟩ ñawpa pacha ‘the ancient times (lit. the times of the ancestors)’[8].

In Classical Quechua, the word seems to have meant ‘the world’ or ‘the universe’ when not modified by other words,. It seems to have had such meaning in important proper names in Inca and Andean cultures such as the theonym ⟨Pachacamac⟩ pacha kama-q ‘universe's supporter, world's creator’[9] and the ruler's name ⟨Pachacuti⟩ pacha kuti-y ‘world's turning’.[10]

These linguistic facts have been interpreted by some scholars as indicating the existence of a cultural specific concept of pacha that would be difficult to translate into European languages. Following such hypothesis, anthropologist Catherine J. Allen translates pacha as ‘world-moment’,[11] and scholar Eusebio Manga Qespi has stated that pacha should be translated as ‘spacetime’ (sic).[12]

Three realms theory[edit]

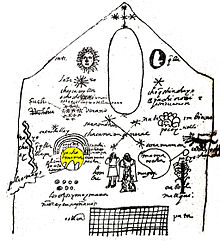

According to some interpretations of Andean culture, there would existe a cultural specific concept imperfectly translatable as ‘realm’ or ‘dimension’.[12][11] This realms theory interprets Quechua compounds used in colonial sources for Christian concepts as evidence for pre-Hispanic native cosmological concepts. That is the case of ⟨hananc pacha⟩ ~ ⟨hanan pacha⟩ hanan pacha ~ ⟨hanac pacha⟩ hanaq pacha, and of ⟨ucu pacha⟩ ukhu pacha ~ ⟨çupaypa guacin⟩ supaypa wasin, which were used for ‘Christian heaven’ and ‘Christian hell’, respectively, since at least the first written Quechua text[13] and first Quechua dictionaries.[14][15]

According to proponents of this interpretation, these realms would have been not solely spatial, but simultaneously spatial and temporal.[16] Although the universe would have been considered a unified system within Inca cosmology,[citation needed] the division between the worlds would be part of the dualism prominent in Inca beliefs, known as yanantin. This dualism found that everything which existed had both features of any feature (both hot and cold, positive and negative, dark and light, etc.).[17]

- Hanan Pacha

The compund hanan pacha (lit. ‘upper pacha’)[18], used for ‘heaven’ in colonial sources, is interpreted as the original name of a cosmological realm that would have included the sky, the sun, the moon, the stars, the planets, and constellations (of particular importance being the milky way). It would have had as Aymara terminological counterpart alax pacha.[19][20] Hanan pacha would have been inhabited by both Inti, the masculine sun god, and Mama Killa, the feminine and moon goddess.[16] In addition, the Illapa, the god of thunder and lightning, also would have existed in the hanan pacha realm.[16] Attested colonial use of the compound would be a reinterpretarion of a preexisting concept.[21]

- Kay Pacha

Kay pacha (Quechua: ‘this pacha’) or aka pacha (Aymara: ‘this pacha’)[19] would have been the perceptible world where people, animals, and plants all inhabit. Kay pacha may have been often impacted by the struggle between hanan pacha and ukhu pacha.[16] This realm would originally have not had the subordination and inferior status in relation to the upper one that it has in Christian conception.[22]

- Ukhu Pacha

In Quechua, ukhu pacha (lit. ‘inferior pacha’)[23] or rurin pacha[citation needed], used for ‘hell’ in colonial sources, would have originally been the inner world. Ukhu pacha would have been associated with the dead as well as with new life.[20] The term would have had as Aymara counterparts manqha pacha ~ manqhipacha.[19] As the realm of new life, the realm is associated with harvesting and Pachamama, the fertility goddess.[24] As the realm associated with the dead, it may have been inhabited by supay. This latter word was the one used by missionaries for Satan, but is interpreted by many anthropologists as the pre-Hispanic name of demon-like creatures which would have tormented the living.[24]

Human disruptions of the ukhu pacha may have been considered a sacred matter, and ceremonies and rituals were often associated with disturbances of the surface.[citation needed] In Inca custom, during the time of tilling for potato crops the disturbance of the soil was met with a host of sacred rituals.[25] Similarly, rituals often brought food, drink (often alcoholic) and other comforts to cave openings for the spirits of ancestors.[24]

When the Spanish conquered the area, rituals about ukhu pacha became crucial in missionary activity and mining operations. Brown contends that the dualistic nature and rituals surrounding openings to ukhu pacha may have made it easier to initially get indigenous laborers to work in the mines.[26] However, at the same time, because mining was considered a perturbation of "subterranean life and the spirits that ruled it; they yielded to sacredness that did not belong to the familiar universe, a deeper and riskier sacredness."[26] In order to insure that the perturbation did not cause evil in the miners or the world, indigenous populations made traditional offering to the supay. However, Catholic missionaries preached that the supay were purely evil and equated them with the devil and hell and thus prohibited offerings.[26] Ritual surrounding ukhu pacha thus retained importance even after Spanish conquest.

Connections between pachas[edit]

Although the different worlds would have been distinct, there would have been a variety of connections between them. Caves and springs would have served as connections between ukhu pacha and kay pacha. Rainbows and lightning would have served as connections between hanan pacha and kay pacha.[20] In addition, human spirits after death could inhabit any of the levels. Some would remain in kay pacha until they had finished business, while others might move to the other levels.[21]

According to other reconstructions, the most significant connection between the different levels was at cataclysmic events called pachakutiy (‘world's turning’[10]). These would have been the instances when the different levels would all impact one another transforming the entire order of the world. These could come as a result of earthquakes or of other cataclysmic events.[16]

Critics of the three realms theory[edit]

Main criticisms to the 3 realms reconstruction appeal to the lack of early colonial written sources in its favor. Terms as ⟨hananc pacha⟩ or ⟨ucu pacha⟩ appear only with their Christian meanings in such documentation.[7] According to historian Juan Carlos Estenssoro, ⟨cay pacha⟩ kay pacha is clearly a missionary neologism, and, while other compounds may have been preexisting, the interpretation of pacha as ‘world’ could be attributed to the Catholic missionaries.[27] Furthermore, renowned linguist Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino attributes the coining of the compounds entirely to Catholic missionaries' lexical planning.[28] Thus, criticism states that the 3 realm model would be an unjustified, anachronistic attribution of Christian beliefs to the Andean pre-Hispanic societies. However, Gregory Haimovich does interpret some passages of Guaman Poma's 1616 chronicle as pointing to the existence of the three realms in pre-Hispanic cosmology.[22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Itier, César (2017). Diccionario quechua sureño: castellano (con un índice castellano-quechua) (1 a edición ed.). Lima, Perú: Editorial Commentarios. p. 154. ISBN 978-9972-9470-9-4.

- ^ a b Torres Menchola, Denis Joel (2019-10-17). Panorama lingüístico del departamento de Cajamarca a partir del examen de la toponimia actual (MA thesis, Linguistics). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. p. 203.

- ^ Ráez, José Francisco (2018). Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (ed.). Diccionario huanca quechua-castellano castellano-quechua. Sergio Cangahuala Castro (Primera edición ed.). Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Instituto Riva-Agüero. p. 202. ISBN 978-9972-832-98-7.

- ^ a b Parker, Gary John (2013). "El lexicón proto-quechua" [Proto-Quechua Lexicon]. In Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo; Bendezú Araujo, Raúl; Torres Menchola, Denis (eds.). Trabajos de lingüística histórica quechua (in Spanish). Lima: Fondo Ed. Pontificia Univ. Católica del Perú. p. 116. ISBN 978-612-4146-53-4.

- ^ Emlen, Nicholas Q. (2017-04-02). "Perspectives On The Quechua–Aymara Contact Relationship And The Lexicon And Phonology Of Pre-Proto-Aymara". International Journal of American Linguistics. 83 (2): 307–340. doi:10.1086/689911. hdl:1887/71538. ISSN 0020-7071.

- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2000). Lingüística aimara [Aymaran Linguistics]. Biblioteca de tradición oral andina. Cuzco: Centro de estudios regionales andinos Bartolomé de Las Casas. p. 365. ISBN 978-9972-691-34-8.

- ^ a b Itier, César (1999). "Szeminski, J. — Wira Quchan y sus obras". Journal de la société des américanistes. 85 (1): 474–479.

- ^ Third Lima Council (2003). "Tercero Catecismo y exposición de la Doctrina Cristiana por sermones (Los Reyes, 1585): Sermones XVIII y XIX". In Taylor, Gérald (ed.). El sol, la luna y las estrellas no son Dios: la evangelización en quechua, siglo XVI. Travaux de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines (in Quechua). Institut français d'études andines (1. ed.). Lima, Perú: IFEA Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos : Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. ISBN 978-9972-623-26-4.

- ^ Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2008). Voces del Ande: ensayos sobre onomástica andina. Colección estudios andinos (1. ed.). Lima, Perú: Fondo Editorial de la Ponrificia Universidad Católica del Perú. pp. 300, 308. ISBN 978-9972-42-856-2.

- ^ a b Cerrón-Palomino 2008, p. 298.

- ^ a b Allen, Catherine J. (1998). "When Utensils Revolt: Mind, Matter, and Modes of Being in the Pre-Columbian". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics (33): 18–27. doi:10.1086/RESv33n1ms20166999. S2CID 132664622.

- ^ a b Manga Qespi, Atuq Eusebio (1994). "Pacha: un concepto andino de espacio y tiempo" (PDF). Revista Española de Antropología Americana. 24: 155–189.

- ^ Santo Tomás, Domingo de (2003). "Plática para todos los indios". El sol, la luna y las estrellas no son Dios: la evangelización en quechua, siglo XVI. Travaux de l'Institut Français d'Études Andines (in Quechua). Institut français d'études andines (1. ed.). Lima, Perú: IFEA Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos : Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. ISBN 978-9972-623-26-4.

- ^ Santo Tomás, Domingo de (2013). Lexicón o vocabulario de la lengua general del Perú : Compuesto por el Maestro Fray Domingo de Santo Thomas de la orden de Santo Domingo. Vol. 1. Lima: Universidad de San Martín de Porres. pp. 151, 349.

- ^ Anonymous (probably Blas Valera) (2014). Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo; Bendezú Araujo, Raúl; Acurio Palma, Jorge (eds.). Arte y vocabulario en la lengua general del Perú. Publicaciones del Instituto Riva-Agüero (Primera edición ed.). Lima: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Instituto Riva-Agüero. pp. 94, 173, 235, 284. ISBN 978-9972-832-62-8. OCLC 885304625.

- ^ a b c d e Heydt-Coca, Magda von der (1999). "When Worlds Collide: The Incorporation Of The Andean World Into The Emerging World-Economy In The Colonial Period". Dialectical Anthropology. 24 (1): 1–43.

- ^ Minelli, Laura Laurencich (2000). "The Archeological-Cultural Area of Peru". The Inca World: The Development of Pre-Columbian Peru, A.D. 1000–1534. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- ^ Gérald Taylor's translation is ‘upper space-time’ (in Santo Tomás 2003). Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino translates the compund as ‘above world’ (Cerrón-Palomino 2008, p. 235).

- ^ a b c Radio San Gabriel, "Instituto Radiofonico de Promoción Aymara" (IRPA) 1993, Republicado por Instituto de las Lenguas y Literaturas Andinas-Amazónicas (ILLLA-A) 2011, Transcripción del Vocabulario de la Lengua Aymara, P. Ludovico Bertonio 1612 (Spanish-Aymara-Aymara-Spanish dictionary)

- ^ a b c Strong, Mary (2012). Art, Nature, Religion in the Central Andes. Austin, Tx: University of Texas Press.

- ^ a b Gonzalez, Olga M. (2011). Unveiling Secrets of War in the Peruvian Andes. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b Haimovich, Gregory (2017-05-19). "Linguistic Consequences of Evangelization in Colonial Peru: Analyzing the Quechua Corpus of the Doctrina Christiana y Catecismo". Journal of Language Contact. 10 (2): 193–218. doi:10.1163/19552629-01002003. ISSN 1877-4091.

- ^ Gérald Taylor's translation is ‘inferior space-time’ (in Santo Tomás 2003). Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino translates the compund as ‘below world’ (Cerrón-Palomino 2008, p. 235).

- ^ a b c Steele, Richard James (2004). Handbook of Inca Mythology. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Millones, Luis (2001). "The Inner Realm". The Potato Treasure of the Andes.

- ^ a b c Brown, Kendall W. (2012). A History of Mining in Latin America. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826351074.

- ^ Estenssoro-Fuchs, Juan Carlos; Castelnau, Charlotte de (1996). "Les pouvoirs de la parole. La prédication au Pérou : de l'évangélisation à l'utopie". Annales. 51 (6): 1225–1257. doi:10.3406/ahess.1996.410918.

- ^ «[...] se hizo la distinción normal, en el quechua sureño propugnado por la iglesia, entre hana pacha ‘mundo de arriba’ (= cielo) y uku pacha ‘mundo de abajo’ (= infierno), aprovechando la disponibilidad de la lengua en cuanto al registro de uku [+bajo, +interior], que simbólicamente parecía ajustarse a la noción del infierno judeo-cristiano [...]» (translation: «[...] in Southern Quechua, a normal distinction, advocated by the Church, was made between hana pacha 'world above' (= heaven) and uku pacha 'world below' (= hell), taking advantage of the availability of the language for the presence of uku [+below, +inner], which symbolically seemed to fit the Judeo-Christian notion of hell [...]»; Cerrón-Palomino 2008, p. 235)