Nadia Chomyn

Nadia Chomyn | |

|---|---|

| Born | October 24, 1967 |

| Died | October 28, 2015 (aged 48) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Drawer |

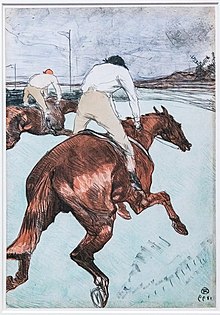

Nadia Chomyn (October 24, 1967 – October 28, 2015) was a British autistic artist who was born in Nottingham. Considered severely handicapped both intellectually and motorically, she is best known for her realistic drawings as a child prodigy, depicting mainly horses and roosters. Nadia's mastery of perspective, and her extremely rapid and precise line drawing from the age of three and a half, earned her the title of "autistic savant". She aroused interest in the anglophone media, psychiatry and art therapy publications in the late 1970s and early 1980s, particularly with regard to the question of whether interventions for autistic children could lead to a parallel loss of other skills.

Nadia never used conventional spoken language, nor was she able to live independently. She was admitted to a specialized institute in early adulthood, and died of a short illness at the age of 48, in relative anonymity. Her drawings are now on display at the Bethlem Royal Archives and Museum in Beckenham, which manages the reproduction rights. They are classified as outsider art.

History[edit]

Early childhood[edit]

All information about Nadia before the age of five years and three months comes from her mother's testimony.[1] Nadia Chomyn was born in Nottingham on October 24, 1967,[2][3] after an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery.[1] She was the second of three siblings,[4] with a younger sister, Tania, and an older brother, Andrej.[5][2]

Her parents, Mychajlo and Aneila Chomyn were both Ukrainian refugees with degrees in science; Mychajlo in electrical engineering, Aneila in chemistry.[4] Having fled the USSR after the war,[2] they began working abroad.[3] Aneila was a laboratory technician,[1] and returned to work when her daughter was a year old.[6] The parents usually spoke their mother tongue, Ukrainian, at home.[7] Aneila soon noticed that Nadia was not developing like a typical baby, with great passivity and little muscle tone.[2] She uttered a few words at the age of nine months, but then stopped talking.[2] She stood upright at one year,[6] but only learned to walk at two,[2] and fell ill with severe measles that same year.[8] Since Aneila returned to work, Nadia was regularly looked after by her paternal grandmother,[6] described as "deeply introverted",[9][8] and who spoke little if at all.[3] Psychiatrist Lorna Selfe noted that Nadia received very little speech stimulation in infancy,[6] but that her brother and sister developed neurotypically, becoming bilingual.[6][2]

Nadia's paternal grandmother took care of her while Aneila was hospitalized for three months with breast cancer, when she was three years old.[9][8][10] She began drawing around the age of three and a half, after her mother returned home for a period of convalescence.[11][8][3] Aneila was very impressed by these achievements.[12] When she was four and a half, a doctor advised her parents to place her in a special school for "slow learners".[4] They noticed that their attempts at schooling were accompanied by progress in their daughter.[4] She took an interest in puzzles and drawing boards, and became independent enough to go to the toilet and feed herself with a spoon.[12] Using only a dozen words, she sometimes sat alone in a room for long periods, sometimes throwing tantrums, and was very slow in her movements.[13] She refused to play with the other children's energetic games,[3] but her drawing skills were impressive.[12]

Diagnosis and follow-up at the University of Nottingham[edit]

Nadia was diagnosed as mentally delayed, with features of autism and severe language delay, by psychiatrist Elizabeth Newson of the University of Nottingham Research Unit,[9] when she was five years and three months old, in 1972.[1][13] She met the four diagnostic criteria of the time.[1] The diagnosis included echolalia, severe motor coordination disorder, cognitive delay and autism-specific affections.[14][15] Newson entrusted Nadia to one of his psychiatry students, Lorna Selfe, who followed her for five years, among other things as part of her master's degree,[9] while she was integrated into the Child Development Research Unit (CDRU).[13] Lorna Selfe noted that Nadia avoided eye contact, was very slow and passive, seemed "in her own world", and that it was extremely difficult to get her attention.[13] Although many toys were available to her, she spent most of her time standing in the middle of the room, staring into space.[13] Selfe assumed that she was a child with severe developmental delay, and testified that she was initially extremely skeptical of the drawings presented by her mother.[16] However, she witnessed a live demonstration, and compared Nadia's drawings to those of Leonardo da Vinci.[16] Elizabeth Newson then questioned her diagnosis of autism, describing Nadia's situation as subnormal.[17]

Nadia failed to cooperate with most of the tests Selfe wanted her to undergo IQ tests, language tests, etc., mastering, according to her, only a dozen words in English, fewer in Ukrainian, and echolalic.[18] According to Selfe, her ability to generalize and form object categories was "extremely limited".[19] Her understanding of spoken language was assessed as equivalent to that of a six-month-old child. On the other hand, she was favored in the understanding of visual elements, and gifted in the completion of puzzles.[1][18] Her score on the Bonhomme drawing test was equivalent to an IQ of 160.[20]

She became known for her highly realistic drawings, produced between the ages of 3 and 9, including in books, on the walls of her home,[21] on cereal packets and on any piece of paper.[17] Throughout her clinical evaluation, her parents brought along drawings she had made at Nottingham University, which were distinguished by an exceptional degree of mastery for a child of her age.[21] During her early days at the CDRU, she also drew pelicans and shoes.[17] Her case represented an enigma for psychiatrists, insofar as her mastery of drawing far surpassed the achievements of typically-developed children,[21] and none of the research publications at the time, based essentially on psychological theories of autism, gave any clue as to how an autistic child could have such drawing abilities.[22] In Nadia's case, a situation of severe disability coexisted with an extraordinary artistic ability.[23]

Specialized school enrollment and media coverage[edit]

When Lorna Selfe left the CDRU, her successors made learning to speak a priority for Nadia.[25] At the age of seven and a half,[26] she was placed at Sutherland House, a specialized school for autistic children,[25] where intensive therapy was applied. Her language skills improved, and she was able to express her needs in short sentences.[25] She showed more social reciprocity, and had fewer tantrums.[26] However, she remained highly non-verbal, and did not communicate in conventional ways.[27] The team at Sutherland House relied for a while on her interest in drawing,[25] but she began to copy the drawings of other children in her school, and produced works more typical of her age,[28] devoid of artistic qualities.[29]

In 1977, Lorna Selfe published her book containing Nadia's drawings (Nadia: A Case of Extraordinary Drawing Ability in an Autistic Child).[30] Her schooling was interrupted by a period of intense media attention, during which American journalist Walter Cronkite travelled to Nottingham to make a film about her.[5] Nadia's live demonstration on CBS also contributed to her popularity.[31] She was invited to appear on several TV shows, and Cronkite tried to get her to appear on a set in the United States.[30]

In adolescence, her drawings became less remarkable, less frequent and more childlike.[30]

Adulthood[edit]

When Nadia was 20, in 1987, an American art-therapy teacher, David R. Henley, suggested that her family observe and support her, with the aim of "awakening" her artistic abilities.[23] He noted that her father, Mychajlo, was a shy man who did not tolerate intrusions into his home.[9] Nadia, who watched a lot of television at the time,[32] initially refused to use the drawing materials he made available to her,[33] and then did not follow his suggestion to draw a horse.[34] She depicted objects from her environment in a simplified way, as well as a self-portrait that was far inferior in quality to her childhood drawings.[34] When Henley gave her a book of her own drawings at the age of 5 and 6, she again produced a less elaborate reproduction than her childhood achievements,[35] although she recognized her earlier drawings.[35] Her other attempts at reproduction were also less dynamic and masterful.[36] Henley noted that Nadia had not made any significant progress in terms of language or autonomy, which made the theory of a loss of her drawing skills alongside the acquisition of other skills hardly credible.[37]

For the rest of her life she was unable to tie her shoes on her own,[31] and to carry out a number of tasks considered basic. Because of her autonomy problems and her father's advanced age, Nadia was placed in a specialized institution under the supervision of Autism East Midlands in early adulthood.[5]

She died at the age of 48, on October 28, 2015, following a short illness.[5] Her father had already passed away, but her brother and sister were, at that time, still alive.[5]

Artistic analysis[edit]

Nadia's drawings are described as being produced extremely quickly, confidently and competently, with very precise lines.[21][38][39] They usually took between a minute and an hour to complete, interspersed with moments of inspection of her work that could last several minutes, before any corrections were made.[21] She could draw a horse's head in two minutes.[40] It seemed that she drew mainly during her moments of joy, and that this activity brought her intense well-being.[21] She did not seem to seek fame or pride in exchange, being very shy about showing her drawings.[41] She was not encouraged to draw by her family,[14] which also had no well-known artists.[20] What's more, her mastery of drawing contrasted with her motor difficulties, such as feeding herself.[12]

Nadia didn't copy everything she saw indiscriminately: she had favorite subjects, which undeniably seemed to bring her pleasure.[38] Horses were always her favorite subject, whether real or carousel horses.[42][21][8] Yet she had very little experience of the outside world, having probably only seen a carousel once or twice in a park during her childhood.[8] She also depicted birds (roosters), trains,[21] feet and shoes, in isolation from the other elements present on the original source of inspiration.[43]

The vast majority of her works were copies, with varying degrees of modification and omission, of other illustrations she had seen.[44] In particular, she took inspiration from a collection of farm animal books featuring horses and roosters, drawn in an adult style from photographs.[8] She worked mainly with ballpoint pen,[9][45] showing no interest in color.[46] Selfe noted that she sometimes forgot elements of the original that inspired her, but that if she showed her the original, Nadia would complete the drawing with the missing elements.[38] She therefore drew from memory,[14][47] usually without having consulted her source of inspiration for some time.[12] Nadia rarely saw horses during her childhood.[10]

Nadia's artistic learning[edit]

Contrary to Pariser's assertion,[44] according to Selfe, Nadia Chomyn did not learn to draw "extremely quickly", but rather developed artistic skills that were inherently different from those of other children,[48] without following the classic known stages.[8] Learning to draw is theoretically preceded by a phase of doodling, then intellectualization in two dimensions, before the ability to make realistic representations is expressed;[49] non-realistic representations therefore usually precede the more realistic ones, in three dimensions.[38]

Nadia incorporated the laws of perspective, proportion and movement into her creations from the age of 3,[50] without first drawing in two dimensions.[44]

Analysis and reception of her drawings[edit]

Nadia's drawings contradicted the theory of a relationship between verbal skills and visual conceptualization, and undermined studies by F. L. Goodenough (Children's drawings, 1931) and D. B. Harris (Harris drawing test manual, 1961), according to which the ability to draw realistically would not exist without verbal intelligence.[45] They also contradicted the theories of gestalt psychology, according to which mental representation always started from a global perception, before the perception of details.[45] Overall, they contradicted all previous generalizations about children's drawings.[1] Lorna Selfe believed that Nadia had this talent for drawing not "despite her disability", but because of her autism.[20]

David Pariser assumed that Nadia's drawings were a "hypertrophy of the scribbling stage", and noted that there was no analytic organization in her representations.[51] He concluded that she was strictly representing her visual universe, without analyzing it.[26] She was, however, capable of adjusting her representations, having, for example, turned to the left a drawing whose original source of inspiration had been turned to the right.[29]

Henley supposed that drawing was a way for her to share her emotional state.[52] David Pariser linked this ability to Nadia's refusal or inability to conceptualize what she was drawing.[3] Tony Charman and Simon Baron-Cohen investigated whether all autistic children were capable of mastering realistic drawing without an intellectualization phase, but this was not the case.[49]

American archaeologist Nicholas Humphrey compared his childhood drawings to cave paintings, particularly those in the Chauvet Cave, noting that his contemporaries had a natural tendency to think that prehistoric man had the same mental reasoning as themselves.[53] He hypothesized that atypical mental functioning without language may have been a prerequisite for making these kinds of representations.[53]

Nadia's drawings have also been compared with those of Leonardo da Vinci,[54] Feliks Topolski,[45] and other autistic people described as savant, such as Stephen Wiltshire.[55] The depth of the gaze of her creations, with eyes that "mirrored the soul", was emphasized,[11] as was her great optical sensitivity to detail.[38]

Reasons for the loss of skills[edit]

The exact reason why Nadia "lost" her artistic skills remains open to many interpretations.[31] She acquired most of her skills between the ages of three-and-a-half and six, her drawings at nine having no technical qualities superior to those of her six years, with instead a loss of her "youthful virtuosity".[44]

American art-therapy teacher David Henley analyzed this as a case of "regression into savant autism".[14] This "regression" is seen as mysterious and sensational.[14] Henley hypothesized that Nadia might have been affected by her mother's death,[56] which occurred when she was 8[31] or 9[30] years old. Lorna Selfe refuted this theory, noting that the quality of the drawings had already diminished beforehand.[30]

She speculated that the absence of language allowed Nadia to develop and maintain a form of visual mental imagery, serving as a means of communication and representation of the world.[21] David Pariser noted that the decline in her drawing skills, around the age of nine, was concomitant with her learning elements of language and social skills.[44] The prevailing theory in the literature is that the behavioral intervention, aimed among other things at suppressing Nadia's repetitive behaviors and restricted interests, had at the same time destroyed her qualities of concentration and focus necessary for drawing.[7] In a commentary on the 1977 book containing her drawings, New York Review of Books journalist N. Dennis was highly critical of the psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers who surrounded Nadia, believing that they had "destroyed" her artistic genius.[57] He drew a parallel between the mutilation of castrati to preserve their vocal talent, and Nadia's attempt at forced "normalization".[57]

Darold Treffert took issue with the theory that instruction and language acquisition led to the loss of "savant" skills in autistic people, citing less high-profile counter-examples.[50] Dr Phil Christie also opposed what he called "a dangerously romantic idea".[58]

Posterity[edit]

Nadia Chomyn aroused great interest in the field of psychiatry, as one of the few known cases of "autistic savant" from infancy to adulthood.[5] Darold Treffert noted that she was one of the very few women described as "autistic savant".[59] Her achievements have inspired publications aimed at characterizing autistic drawing: C. Park identified as common characteristics an initial lack of interest in color, a preference for stereotyped and derivative subjects, a use of line drawing, an unusual capacity for memory work, and an ability to render what is strictly perceived by sight.[60]

Her drawings are now held at the Bethlem Royal Archives and Museum in Beckenham,[5] which owns around 200 of them[61] and manages their licensing.[62] They are considered outsider art.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Park (1978), p. 458

- ^ a b c d e f g Selfe (2012), p. 19

- ^ a b c d e f Pariser (1981), p. 20

- ^ a b c d Golomb, Claire (2004). L. Erlbaum Associates (ed.). The Child's Creation of a Pictorial World. p. 262. ISBN 1-4106-0925-1. OCLC 53482696.

- ^ a b c d e f g Selfe, Lorna (December 9, 2015). The Guardian (ed.). "Nadia Chomyn Obituary". TheGuardian.com. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Park (1978), p. 459

- ^ a b Henley (1989), p. 45

- ^ a b c d e f g h Selfe (2012), p. 20

- ^ a b c d e f Henley (1989), p. 46

- ^ a b Park (1978), p. 460

- ^ a b Henley (1989), p. 52

- ^ a b c d e Selfe (2012), p. 22

- ^ a b c d e Selfe (2012), p. 23

- ^ a b c d e Henley (1989), p. 43

- ^ Selfe (1977e), p. 7

- ^ a b Selfe (2012), p. 24

- ^ a b c Selfe (2012), p. 27

- ^ a b Selfe (2012), p. 28

- ^ Selfe (1977d), p. 124

- ^ a b c Park (1978), pp. 464–465

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Selfe (1977b), pp. 31–48

- ^ Selfe (1977c), p. 21

- ^ a b Henley (1989), p. 44

- ^ Selfe (2012), pp. 31–32

- ^ a b c d Selfe (2012), p. 30

- ^ a b c Pariser (1981), p. 26

- ^ Sedgwick, Fred (2013). Taylor and Francis (ed.). Enabling Children's Learning Through Drawing. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-134-14198-2. OCLC 862049477.

- ^ Selfe (2012), p. 32-33

- ^ a b Park (1978), p. 457

- ^ a b c d e Selfe (2012), p. 34

- ^ a b c d Henley, David R. (2017). Creative Response Activities for Children on the Spectrum: A Therapeutic and Educational Memoir. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-87474-3. OCLC 1005843020.

- ^ Henley (1989), p. 55

- ^ Henley (1989), p. 47

- ^ a b Henley (1989), p. 48

- ^ a b Henley (1989), p. 49

- ^ Henley (1989), p. 50

- ^ Henley (1989), p. 51

- ^ a b c d e Pariser (1981), p. 23

- ^ Park (1978), p. 463

- ^ Park (1978), p. 464

- ^ Milbrath, Constance; Siegel, Bryna (1996). "Perspective Taking in the Drawings of a Talented Autistic Child". Visual Arts Research. 22 (2): 56–75. JSTOR 20715882.

- ^ Cox, Maureen V. (2004). Cambridge University Press (ed.). The Pictorial World of the Child. Cambridge University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-521-82500-9. OCLC 60794228.

- ^ Pariser (1981), p. 24

- ^ a b c d e Pariser (1981), p. 22

- ^ a b c d Pariser (1981), p. 21

- ^ Park (1978), p. 467-468

- ^ Selfe (2012), p. 26

- ^ Selfe (1977f), p. 127

- ^ a b Charman, Tony; Baron-Cohen, Simon (June 1993). "Drawing Development in Autism: The Intellectual to Visual Realism Shift". British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 11 (2): 171–185. doi:10.1111/j.2044-835x.1993.tb00596.x. ISSN 0261-510X.

- ^ a b Treffert (2010), pp. 26–27

- ^ Pariser (1981), p. 25

- ^ Henley (1989), p. 53

- ^ a b Humphrey, Nicholas (October 1998). "Cave Art, Autism, and the Evolution of the Human Mind". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 8 (2): 165–191. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001827. ISSN 1474-0540. S2CID 5377414.

- ^ Brooks Platt, Carole (2015). Andrews UK (ed.). In Their Right Minds: The Lives and Shared Practices of Poetic Geniuses. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-84540-838-1. OCLC 941700318.

- ^ Kindler, Anna (1997). National Art Education Association (ed.). Child Development in Art. National Art Education Association. ISBN 0-937652-77-6. OCLC 37815960.

- ^ Henley (1989), p. 54

- ^ a b Dennis, N. (May 4, 1978). "Portrait of the Artist". New York Review of Books (25): 8–15.

- ^ Feinstein, Adam (2011). John Wiley & Sons (ed.). A History of Autism: Conversations with the Pioneers. John Wiley & Sons. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4443-5167-5. OCLC 897591678.

- ^ Treffert, Darold (2005). "The Savant Syndrome in Autistic Disorder". In Nova Publishers (ed.). Recent Developments in Autism Research. Nova Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 1594544972.

- ^ Park (1978), p. 470

- ^ "In the Frame for January 2013: Nadia Chomyn". Bethlem Museum of the Mind. January 3, 2013.

- ^ "Nadia Chomyn – Gallery". Bethlem Museum of the Mind. Retrieved 2018-05-03.

Bibliography[edit]

- Henley, David R. (1989-07-01). "Nadia Revisited: A Study into the Nature of Regression in the Autistic Savant Syndrome". Art Therapy. 6 (2): 43–56. doi:10.1080/07421656.1989.10758866. ISSN 0742-1656.

- Pariser, David (1981). "Nadia's Drawings: Theorizing About an Autistic Child's Phenomenal Ability". Studies in Art Education. 22 (2): 20–31. doi:10.2307/1319831. JSTOR 1319831.

- Park, C. (1978). "Book Review of Nadia". Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia. 8 (4): 457–472. doi:10.1007/BF01538050. S2CID 198201413.

- Paine, Sheila (1981). Six Children Draw. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-543950-4.

- Selfe, Lorna (November 21, 1977a). Nadia : A Case of Extraordinary Drawing Ability in an Autistic Child. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-635750-1.

- Selfe, Lorna (1977b). "A Single Case Study of an Autistic Child with Exceptional Drawing Ability". In George Butterworth (ed.). The Child's Representation of the World. Boston, MA: Springer. pp. 31–48. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2349-5_2. ISBN 978-1-4684-2351-8.

- Selfe, Lorna (2012). Psychology Press (ed.). Nadia Revisited: A Longitudinal Study of an Autistic Savant. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-136-78932-8.

- Treffert, Darold A. (2010). Kingsley, Jessica (ed.). Islands of Genius : The Bountiful Mind of the Autistic, Acquired, and Sudden Savant. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85700-318-8. OCLC 699506917.

External links[edit]

- "Rider drawing by Nadia Chomyn, aged 5".

- "Nadia Chomyn – Gallery". Bethlem Museum of the Mind.