Mitsivarniannga

Mitsivarniannga (1860 – 1910) was an angakkuq (a Greenlandic shaman) who created tupilai. He was among the first Greenlandic artists to produce tupilai, when between 1905 and 1906, he created a series of replicas for a Danish researcher made of driftwood and child body parts, including teeth, eyes, and skin. His son was Kârale Andreassen, who drew one of his tupilai, which was created in response to the death of Mitsivarniannga's brother.

Life and career[edit]

Mitsivarniannga was born in 1860.[1]

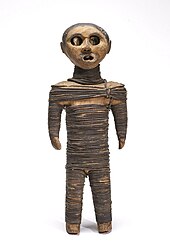

Tupilai were figures which caused misfortune.[2] During the Danish conquest of Greenland, settlers attempted—but never succeeded—in furnishing authentic tupilai; artists began to create replicas, which they would then sell.[2] Between 1905 and 1906, Mitsivarniannga created one of the first tupilaq replicas for a Danish researcher, William Thalbitzer, which depicted a tupilaq that harassed Mitsivarniannga's family; these were made of child body parts (including teeth, eyes, and skin) and driftwood.[3] This broke the taboo of not showing settlers tupilai, and other artists began to create tupilaq figures.[4]

The settlers and missionaries allowed for East Greenlandic cultural traditions to continue on, and as a result of this sympathetic approach, Mitsivarniannga was among the first shamans to convert to Christianity.[5]

Mitsivarniannga's son was Kârale Andreassen, a catechist.[6] In the 1920s, Andreassen drew one of his father's tupilai, which was created in response to the death of Mitsivarniannga's brother.[6] According to Mitsivarniannga, the tupilaq was created with pieces of his brother's body (including his head), a dead snow bunting, and seal tendons.[6] After assembling the tupilaq, he said it came alive and flew away to avenge the death of his brother.[7]

Mitsivarniannga died in 1910.[8] A book of Greenlandic songs has one about challenging him from 1935.[9]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Zackel 2008, p. 67.

- ^ a b Kaalund 1983, p. 67.

- ^ Kaalund 1983, p. 68.

- ^ Nuttal 2005, p. 2075.

- ^ Petersen 1984, p. 634.

- ^ a b c Kaalund 1983, p. 24.

- ^ Kaalund 1983, p. 26.

- ^ Zackel 2008, p. 97.

- ^ Victor 1991, p. 107.

Bibliography[edit]

- Kaalund, Bodil (1983). The art of Greenland: Sculpture, crafts, painting. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520048409.

- Nuttal, Mark (2005). "Tupilak". Encyclopaedia of the Arctic. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781136786808.

- Petersen, Robert (1984). "East Greenland before 1950". In Damas, David (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9780160045806.

- Victor, Paul-Emile (1991). Chants d'Ammassalik [Songs of Ammassalik] (in French, Danish, and Kalaallisut). Kommissionen for videnskabelige Undersøgelser i Grønland. ISBN 9788750391593.

- Zackel, Christine (2008). "Von der Kolonie zur Autonomie" [From colony to autonomy]. Indianer: Ureinwohner Nordamerikas [Indians: Native Americans] (in German). Schallaburg: Schallaburg Kulturbetriebsges. ISBN 9783950234329.