Manning Johnson

Manning Rudolph Johnson AKA Manning Johnson and Manning R. Johnson (December 17, 1908 – July 2, 1959)[1] was a Communist Party USA African-American leader and the party's candidate for U.S. Representative from New York's 22nd congressional district during a special election in 1935. Later, he left the Party and became an anti-communist government informant and witness.

Background[edit]

Manning Rudolph Johnson was born on December 17, 1908, in Washington, DC. He attended Lovejoy Elementary School, Lovejoy Junior High School, and the Armstrong Technical High School. He graduated from the Naval Air Technical School (at Naval Support Activity Mid-South, then in Memphis, Tennessee, now at Naval Air Station Pensacola).[2] [3][4]

In 1932, he studied for three months by J. Peters, William Z. Foster, Jack Stachel, Alexander Bittelman, Max Bedacht, Israel Amter, Gil Green, Harry Haywood, and James S. Allen among others at the "National Training School," part of the New (York?) Workers School, a "secret school" devoted to training "development of professional revolutionists, professional revolutionaries, or active functionaries of the Communist party."[2][5] Tuition was free with expenses paid and accommodations provided at the "Cooperative Colony" (Allerton Avenue, the Bronx) (now known as the United Workers Cooperatives). Jacob Golos of World Tourists provided transportation via the "Martell Bus Line."[5]

Career[edit]

Communist[edit]

From 1930 to 1939, Manning Johnson was a member of the Communist Party USA; he left shortly after the announcement of the Hitler-Stalin Pact.[2] He served as a national organizer for the Trade Union Unity League.[5] From 1931 to 1932, he served as a District agitation propaganda director for Buffalo, New York.[2] From 1932 to 1934, he was district organizer for Buffalo.[2][5] In 1935, Manning Johnson ran as a Communist Party candidate for New York's 22nd Congressional District for the United States House of Representatives. From 1936 to 1939, he served on the Party's National Committee, National Trade Union Commission, and Negro Commission.[2][5][8] Fellow members of the Party's national Negro Commission were: James S. Allen, Elizabeth Lawson, Robert Minor, and George Blake Charney.[3] Johnson knew Steve Nelson "very well." From 1930 "until the American party, on the surface, severed" ties, the CPUSA followed the Communist International ("Comintern").[5]

Johnson claimed later to have left the Communist Party because of his original religiosity, his disagreement with the Party's promotion of a Soviet Negro Republic in the Black Belt in the American South, and the insincerity of the Party in saving the Scottsboro Boys. The final straw was the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939.[5]

Anti-Communist[edit]

After leaving the Communist Party, Johnson said, he found Communists constantly trying to keep him out of the (non-communist) labor movement.[5]

During World War II, Johnson served in the United States Navy.[5]

By his own estimation in 1950, Johnson testified in 18-20 cases as a witness for the government.[2]

In 1947, Johnson served for the first time as a government witness, this time in a case against Gerhart Eisler.[2]

In 1948, Johnson and George Hewitt testified before the Canwell Committee in the State of Washington that University of Washington professor Melvin Rader had been a communist.[4][8]

As of 1949, Johnson was worked as an "international representative" of the Retail Clerks' International Association (Retail Clerks International Union), which he claimed was the eighth largest union member with the American Federation of Labor thanks to a membership of 250,000.[5]

On July 14, 1949, Johnson testified on "Communist Infiltration of Minority Groups":

- Black Belt, Soviet Negro Republic: Johnson described his experience in the Communist party (described above in this entry). Next, he described the Communist Party's efforts to set up an autonomous Soviet Negro Republic in the US "Black Belt". This policy derived on Lenin's principe of self-determination for national minorities. Thus, the Comintern considered African-Americans a national minority. The Party started enacting this effort by forming a Sharecroppers' Union (1931) and "other organizations in the South." Johnson agreed when asked by HUAC that the Communist Party intended this Black Belt, Negro republic to "secede from the Union" and to do so "by force and violence, if necessary." However, Johnson explained, "I would say this, that the majority of Negroes who were attracted to the Communist Party never understood that particular phase of the policy."[5]

- National Negro Congress: Johnson described the development of the American Negro Labor Congress, into the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, into the National Negro Congress (NNC). James W. Ford was to run the NNC. Eventually, non-communist A. Philip Randolph emerged as leader. At the third NNC convention, Randolph quit when he found the NNC packed communist members, who were already fighting him. Johnson criticized James W. Ford as incompetent; he even came under party discipline (by a committee headed by Jacob Golos and Charles Dirba) for recommending Robeson over Ford. Johnson also said that the NNC received funds from Popular Front organizations like the International Workers Order if they ran into financial trouble.[5]

- Scottsboro Boys: Johnson also criticized the Party for its handling of the Scottsboro Boys case, particularly when sending Benjamin J. Davis Jr. to have Samuel Leibowitz removed as counsel. Johnson noted how Mike Quill had helped set up the Transport Workers Union as communist but then left the communist movement himself. Johnson also made many anti-communist, sloganeering statements throughout his testimony, e.g., "Human life, to Communists, is cheap" and "Paul Robeson, who wishes to become the Black Stalin." Of other African-American organizations, he noted "The record of the NAACP has been remarkably fine."[5]

- Cuban Support: Johnson said he had traveled as secretary of the "American Commission to Cuba" with chairman Clifford Odets to "help revolutionary forces there" in support of "Grau San Martin" (Ramón Grau).[5]

- List: Johnson produced a list of Communist-front organizations that included: African Blood Brotherhood (headed by Richard B. Moore and Cyril Briggs), All Harlem Youth Conference, American Negro Labor Congress, Artists Committee for Protection of Negro Rights, Citizens Committee for the Appointment of a Negro to the Board of Education, Civil Rights Congress, Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service and Training, Committee for the Negro in the Arts, Committee to Abolish Peonage, Committee to Aid the Fighting South, Committee to Defend Angelo Herndon, League of Young Southerners, Council on African Affairs, Defense Committee for Claudia Jones, George Washington Carver School, Harlem Committee to End Police Brutality, Harlem Council on Education, International Committee of Negro Workers, International Committee on African Affairs, International Trade Union Committee for Negro Workers, International Workers Order, League for Protection of Minority Rights, League of Struggle for Negro Rights, National Conference of Negro Youth, National Emergency Committee to Stop Lynching, National Negro Congress, National Student Committee for Negro Problems, Negro Cultural Committee, Negro Labor Victory Committee, Negro People's Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, Scottsboro Defense Committee, Southern Negro Youth Congress, Southern Youth Legislature, United Aid for Peoples of African Descent, United Front for Herndon, United Harlem Tenants and Consumers Organization, and United Negro and Allied Veterans of America among others.[5]

Johnson also testified against Paul Robeson accusing him of having been a member of the Communist Party, although Johnson said "in the Negro commission of the national committee of the Communist Party we were told, under threat of expulsion never to reveal that Paul Robeson was a member of the Communist Party, because Paul Robeson's assignment was highly confidential and secret."[5] During 1949 testimony, Johnson summed up Robeson's career by saying, "It is regrettable, indeed, that such a man has sold himself to Moscow. He has enjoyed many of the benefits of this country.[5]

In December 1949 during the perjury trial of labor union leader Harry Bridges, Johnson was a government witness. TIME magazine reported his testimony. In 1936, Johnson had taken part in the Party's National Committee re-election of Bridges under the alias "Rossi." When James M. MacInnis, defense attorney, confirmed that Johnson had not seen him since then, Johnson explained, "The reason I didn't see him again was because, at the national committee meeting at which Harry Bridges was introduced... Jack Stachel said to the meeting that in the future Harry Bridges would not be brought to committee meetings for security reasons." Johnson's testimony hurt Bridges defense from 1945 naturalization proceedings, when he denied Communist Party membership.[9][10]

In 1950, Johnson testified against the International Workers Order.[2]

In 1953, Johnson testified before the Committee on Un-American Activities of the U.S. House of Representatives, 83rd Congress. Robert L. Kunzig, chief counsel for the committee, asked "Was deceit a major policy of Communist propaganda and activity?" Manning R. Johnson answered, "Yes, it was. They made fine gestures and honeyed words to the church people which could be well likened unto the song of the fabled sea nymphs luring millions to moral decay, spiritual death, and spiritual slavery...".[11][12]

In May 1954, Johnson testified against Ralph Bunche before the International Organizations' Employees Loyalty Board, as did Leonard Patterson.[8]

In a July 1954 article entitled "The Profession of Perjury," Professor Melvin Rader attacked Johnson's credibility:

Johnson's entire testimony was false; the facts were told by Edwin O, Guthman of the Seattle Times in articles which won the Pulitzer prize for the best national reporting of 1949, and by Vern Countryman, Professor of Law at Yale University in Un-American Activities in the State of Washington, Cornell University Press, 1951... Even though the facts that prove Johnson a perjurer have been widely publicized, he has continued his career as a consultant and professional witness in the employ of the Justice Department.[8]

In 1955, United States Supreme Court justices agreed that Paul Crouch and Manning Johnson had made allegations under perjury.<Note a citation. What Pages?> Lichtman, Robert M. (2012). The Supreme Court and McCarthy-Era Repression: One Hundred Decisions. University of Illinois Press. p. 82. Retrieved 15 June 2016.</ref> On March 21, 1955, Pravda listed FBI informants and their payments, including Louis F. Budenz at $10,000 annually from the United States Treasury "as a paid perjurer," Paul Crouch at $9,675 from the United States Department of Justice in less than two years, and Manning Johnson $9,000.[13]

Attacks on NAACP[edit]

While testifying for Congress, Johnson spoke positively about the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In July 1949, for example, he said, "The record of NAACP has been remarkably fine."[5] (During the same set of hearings, HUAC investigator Alvin Williams Stokes said, "I think it is something that should go on record. I think this is a proper point to state that were it not for the NAACP, which has fought and is still fighting to legally correct injustices, the Urban League, to which much credit must be given for the continuing accelerated integration of Negroes in the industrial and business life of the Nation, and the many city commissions on human relations and unity, together with hundreds of Protestants, Catholics, and Jewish ministerial and interracial councils, what success communism may have obtained among Negroes must be left to speculation."[5])

In his last years, however, Johnson spoke negatively about the NAACP. During an undated recorded speech known as "Manning Johnson's Farewell Address," he stated:

The NAACP collects millions of dollars through racial incitement. They go out of their way to create race issues, because the more race issues they create the more they have got an appeal for begging for funds, but what do they do with that money. What do they do with it?[14]

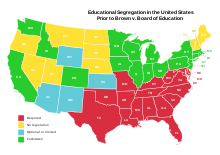

An issue which he attacked in that speech was NAACP support for racial integration. He said, "This integration stuff has gone to all sorts of extremes."[14] For instance, he said "Now the NAACP has gotten a token number of Negroes integrated in schools... a Pyrrhic victory" and that the "Supreme Court, in its decision, upset the question of separate but equal, educational facilities,"[14] thus attacking the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision. Johnson noted, "What is significant, that this whole integration campaign coincided with Russia’s stepped-up campaign in Africa and Asia,"[14] implying some Communist influence. Johnson clearly was concerned with racial equality in this same issue. He was concerned:

The Supreme Court, by its decision, has relieved the South of all its responsibility to equalize educational facilities in the South. The Supreme Court doesn't make appropriations. It doesn't. And if the legislators in the Southern States don’t make the appropriations to equalize schools the Supreme Court's not going to do it, and you can't force them to do it. And the result is that they have relieved the South of any responsibility to equalize the education for Negroes.[14]

Clearly, Johnson felt Brown v. Board of Education was a mistake:

What the Supreme Court did was open the Pandora box. They have created the fertile soil for the operation of the worst type of elements on both sides. And as a result of this, race relations have been set back 50 years in this country.[14]

Referring again and again to "Red" or "Russian" support for the African nationalist movement,[14] Johnson seems to have drawn on his US experience in promoting a Negro Soviet Republic in the Black Belt with the African nationalist movement two decades later. Like many ex-Communists, he continued to see Communist influence, as he directly stated: "Beneath all of the racial unrest, at the root of all racial unrest in the country, is the clammy, cold, bloody hand of Communism."[14]

Personal life and death[edit]

In a December 26, 1949, a Time magazine article entitled "You'd Be Thin, Too" described him as a "husky, big-jawed... smooth, deep-voiced Negro."[9]

During the late 1930s, Johnson was a member of the American League Against War and Fascism.[5]

Johnson wrote of poet Claude McKay that "I knew [him] very well."[15]

Manning Johnson died following an auto accident which had occurred on June 26, 1959 just south of Lake Arrowhead Village, California. He is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, California.[16]

Legacy[edit]

During the July 1949 hearing into Communist infiltration of minority groups, Manning told HUAC of his interactions with HUAC investigator Alvin Williams Stokes. He said that Stokes "talked to us in New York about 2 years ago and convinced me I should take part before this committee."[5] Johnson also stated (without prompting from the committee):

The information that you have gotten from me today was not prepared before I came here. Mr. Stokes spoke to me about a couple years ago in New York, and met with me again several months ago, and I discussed with him some of the things which I have put in the record. They are more or less familiar to me. To answer some of the questions you ask thoroughly and as they should be answered would necessitate my refreshing my recollection and checking on certain records and so forth which I have. I will be glad to come at any future time to assist you in establishing the facts as to Communist activities in this republic.[5]

In 1966, W. Cleon Skousen called Johnson "the most important Negro Communist in the United States."[17] In 1981, Victor S. Navasky (then, publisher of The Nation magazine and who refers to Johnson only with the epithet "informant") documented Manning Johnson's 1951 admission to lying in 1949 during the second trial of Harry Bridges:

In 1951, Johnson admitted to patriotic lying:Q: In other words, you will tell a lie under oath in a court of law rather than run counter to your instruction from the FBI. Is that right?

Johnson: If the interests of my government are at stake. In the face of enemies at home and abroad, if maintaining secrecy of the techniques and methods of operation of the FBI, who have responsibility of the protection of our people, I say I will do it a thousand times.[18][additional citation(s) needed]

Works[edit]

Writings of Johnson include:

- "Party Organizer" (1933)[5]

- "An American Holiday" (1939)[5]

- Color, Communism, and Common Sense (1958)

Johnson's book, Color, Communism, and Common Sense, was quoted by G. Edward Griffin in his 1969 motion picture lecture More Deadly than War ... the Communist Revolution in America.[19] Archibald Roosevelt, a son of US President Theodore Roosevelt, wrote the book's preface as president of The Alliance, Inc.[20] In describing his Communist experience, he claimed that the CPUSA was under the control of the Soviet Politburo, of which he claimed to be a member, and that Gerhart Eisler (named in 1946 by Louis F. Budenz as head of Soviet espionage in the USA) was the Soviet's country representative.[3] The book's table of contents lists:

- Preface by Archibald B. Roosevelt

- I. In the Web

- II. Subverting Negro Churches

- III. Red Plot to Use Negroes

- IV. Bane of Red Integration

- V. Destroying the Opposition

- VI. The Real “Uncle Toms”

- VII. Creating Hate

- VIII. Modern Day Carpet Baggers

- IX. Race Pride is Passé

- X. Wisdom Needed

- Appendices[21]

Johnson claimed that the Communist Party controlled the unions including American Negro Labor Congress, League of Struggle for Negro Rights, International Labor Defense, National Negro Congress, Sharecroppers' Union, Civil Rights Congress, Negro Labor Victory Committee, Southern Negro Youth Congress, and Negro Labor Councils.[15] (NOTE: International Labor Defense was not a union but a legal defense group.) In the book's appendix, Johnson attacked Howard University.[22]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Larrowe, Charles P. (1972). Harry Bridges; the rise and fall of radical labor in the United States. L. Hill. p. 311. ISBN 9780882080000.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Court of Appeals of the State of New York. County Clerk's Index. 1951. pp. 1180-1363 (all testimony), 1180 (birth), 1183-1184 (CPUSA service), 1294-1295 (witness against Gerhart Eisler), 1295 (18-20 cases). Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Manning (1958). "In the Web". Color, Communism, and Common Sense. Alliance, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Transcript of the Proceedings of the Un-American Activities Committee" (PDF). University of Washington. 29 January 1948. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Hearings Regarding Communist Infiltration of Minority Groups. US GPO. 1949. pp. 497–521. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Allen, James S. (1932). The American Negro. International Publishers. p. 5 (map). Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Allen, James S. (April 1936). The Negro Question in the United States (PDF). International Publishers. p. 19 (map). Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Rader, Melvin (5 July 1954). "The Profession of Perjury". The New Republic. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b "You'd Be Thin, Too". TIME. 26 December 1949. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Davies, Lawrence (December 14, 1949). "Bridges is termed leading Red in '36: Johnson, Ex-Communist, Says Union Leader Was Elected National Committee Member". New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Quoted in Treason in the Church: Trading Truth for a "Social Gospel" (www.crossroad.to).

- ^ United States. Investigation of Communist Activities in the New York City Area ... Hearings Before the Committee on Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Third Congress, First Session. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off, 1953. OCLC 34990883

- ^ Strategy and Tactics in World Communism: The Significance of the Matusow Case. USGPO. 22 February 1955. p. 1233. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Johnson, Manning (1958). "In the Web". Color, Communism, and Common Sense. Alliance, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ a b Johnson, Manning (1958). "Red Plot to Use Negroes". Color, Communism, and Common Sense. Alliance, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ National Cemetery Administration. U.S. Veterans' Gravesites, ca.1775-2006 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006. Ancestry, Inc. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ Skousen, W. Clean (1966). The Communist Attack on U.S. Police. Verity Publishing. ISBN 9780934364614. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "G. Edward Griffin - More Deadly Than War: The Communist Revolution in America - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-12-20. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ^ Archibald Roosevelt (1958). Preface. Color, Communism, and Common Sense. By Johnson, Manning. Alliance, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Manning (1958). "Contents". Color, Communism, and Common Sense. Alliance, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Manning (1958). "Appendices". Color, Communism, and Common Sense. Alliance, Inc. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

External links[edit]

- African-American non-fiction writers

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- American communists

- American political writers

- American male non-fiction writers

- American anti-racism activists

- 1964 deaths

- 1908 births

- Communist Party USA politicians

- American anti-communists

- Black conservatism in the United States