MV Geysir

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Geysir |

| Owner | TransAtlantic Lines LLC |

| Port of registry | |

| Route | United States – The Azores |

| Builder | Equitable Shipyard Inc., Madisonville, Louisiana |

| Yard number | 1716[2] |

| Laid down | 1 January 1977 |

| Launched | 20 January 1979 |

| Completed | 1980 |

| Identification |

|

| Status | In service[3] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | General cargo ship[1] |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 90.1 m (296 ft) LOA[2] |

| Beam | 13.7 m (45 ft)[2] |

| Depth | 6.7 m (22 ft)[2] |

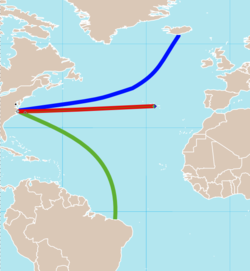

Approximate routes of the Geysir: From the U.S. East Coast to Iceland, Azores, and Brazil.

| |

MV Geysir is a U.S.-flagged general cargo/container ship owned by TransAtlantic Lines LLC. Originally named Amazonia, the 90-meter ship was built by American Atlantic Shipping in 1980 to serve a route from the United States to Brazil. In 1983, the ship was seized by the United States Maritime Administration for nonpayment of government loans.

In 1984, it was renamed Rainbow Hope and leased by a small startup company to serve a route between the United States and the American military base at Keflavik, Iceland. As Rainbow Hope the ship was central in an international disagreement between the United States and Iceland that would span years, be compared by The Chicago Tribune to the plot of the movie The Mouse That Roared, and involve political personalities including Antonin Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Ken Starr, Elizabeth Dole, George Shultz, and Ronald Reagan.[4]

After finally losing the Iceland route, the ship was renamed Juno, bought by Norwegian owners and worked in the Norwegian trade from 1996 to 1999. In 1999, it was bought by TransAtlantic Lines, renamed Geysir and put back on the U.S.–Iceland route, leading to further tensions between the United States and Iceland. After the 2006 closing of the United States Naval Station in Keflavik, the ship has gone on to carrying cargo to U.S. activities in the Azores.

Construction[edit]

Then named Amazonia, the ship's keel was laid on 1 January 1977 at Equitable Shipyard in Madisonville, Louisiana.[2] Its hull, constructed from ordinary strength steel,[5] has an overall length of 90.1 metres (296 ft), a beam of 13.7 metres (45 ft), and a moulded depth of 6.7 metres (22 ft).[2] Its three general cargo holds have a total bale capacity of 2,945 cubic metres (104,000 cu ft) or grain capacity of 3,341 cubic metres (118,000 cu ft).[5][6] The ship has a gross tonnage of 2,266 GT and a total carrying capacity of 2,032 long tons deadweight (DWT).[2]

Amazonia was built with eight ballast tanks, having a total ballast capacity of 770 cubic metres (27,000 cu ft).[5][6] Other major features of the ship's structure include its five diesel oil tanks, two lubricating oil tanks, two potable water tanks, a chain tank, and a waste water tank.[5] The ship was built with two cranes, which have since been removed.[7]

The ship features a MAN B&W Diesel A/S 8L28/32A main engine with eight 280-millimetre (11 in) cylinders with a 320-millimetre (13 in) stroke for maximum continuous power of 1,961.98 kilowatts (2,631.06 hp) driving a bronze propeller.[8] Electrical power is generated by two 400 kilowatts (540 hp) auxiliary generators.[8] Construction of the ship was completed in 1980.[2]

History[edit]

In the early 1980s, the company American Atlantic Shipping, a wholly owned subsidiary of American Maritime Industries, built three 2,000 DWT multi-purpose ships to carry cargo between the United States and Brazil: the Amazonia and her two sister-ships, America and Antilla.[9][10][11] In 1983, the United States Maritime Administration took possession of the three ships after American Atlantic defaulted on Title XI[12] payments.[13]

Rainbow Hope[edit]

In May 1984, entrepreneur Mark W. Yonge of Monmouth County, New Jersey founded Rainbow Navigation for the sole purpose of serving the route between the United States and United States military base at Keflavik, Iceland.[14][15] Using money he earned from a ship-chartering company, Yonge chartered Amazonia from the Department of Transportation and renamed it Rainbow Hope.[15] The company consisted of one ship, a crew of 22, and seven full-time employees.[15] Icelandic companies had serviced the Iceland route since the late 1960s.[14] Yonge submitted a bid quoting the same rates that the Icelandic companies were charging and invoked the Cargo Preference Act of 1904.[14] Rainbow won an $11 million contract to carry 70% of the cargo on the route, and immediately began to work the route under contract to the Military Sealift Command.[14][16]

According to an official of the U.S. State Department speaking on the condition of anonymity, "Almost right at the start, Iceland let their feelings be known about losing the business... For the Icelanders, who are entirely dependent on seagoing trade, it was an issue of national sovereignty."[15] Minister Counselor for the Icelandic Embassy in Washington, Hordur Bjarnason informed the Reagan Administration that Iceland "could not accept that a foreign shipping company would have a monopoly on carrying the cargo to Iceland."[15]

Before Rainbow Hope ever left the pier, the Department of Transportation approached Rainbow trying to defuse the situation.[15] The New York Times characterized the ensuing fight as Rainbow Navigation versus "the Navy, the National Security Council and the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Transportation to the President himself."[15] During 1985, Iceland raised the matter with the United States Department of State at least six times,[17] including a meeting in Lisbon in June of that year between Secretary of State George Shultz and Foreign Minister of Iceland Geir Hallgrimsson.[18] Shultz described the matter as a "major irritant in U.S.–Icelandic relations"[15] and relations were strained to the point that Iceland threatened to start boarding U.S.-flagged ships and to close the Keflavik base.[17][19]

Shultz's State Department attempted to solve the problem in a number of ways. It tried and failed to have the 1904 Cargo Preference Act amended.[17] It made an offer to pay Icelandic shipping firms monetary damages for loss of the route, which was refused.[17] President Reagan asked United States Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman, Jr. to determine if Rainbow's claim under the Cargo Preference Act was valid,[15] and on 8 August 1985, Lehman declared Rainbow's rates to be "excessive and unreasonable."[18] Within four days, Rainbow pressed suits in United States District Court against "the Department of the Navy and various other federal agencies" as well as "the Secretary of the Navy and various other government officials in their personal capacities."[17] The suits demanded declaratory and injunctive relief from the federal agencies and monetary damages from the named individuals.[17] The International Organization of Masters, Mates & Pilots, representing Rainbow Hope's crew, joined Rainbow in the suits.[17]

On 15 October 1985, the District Court issued its order, granting Rainbow's requests for declaratory and injunctive relief, and ordered the government to withdraw a call for new bids.[17] The government appealed the finding. On 27 January 1986, the panel of the D.C. Circuit Court of appeals consisting of future Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, future Starr Report special prosecutor Kenneth Starr and Senior Circuit Judge Carl E. McGowan upheld Rainbow's victory.[20] During the appeal, the government's attorneys conceded that Lehman's finding of Rainbow's rates to be "excessive and unreasonable" was politically motivated,[18] and the court found some arguments put forth by Shultz and Lehman "extraordinary" and having "no rational basis".[15] In particular, Scalia wrote that the "factual basis for (Lehman's) assertion (wa)s utterly lacking."[18] During this time, Transportation Secretary Elizabeth Dole supported Rainbow, according to the Chicago Tribune, as a viable employer of United States mariners.[19]

Eight months later, the government took a different approach to solve its problem with Rainbow, in the form of the 1986 Treaty Between the United States of America and the Republic of Iceland to Facilitate Their Defense Relationship.[21] This treaty, negotiated by future Secretary of Veteran Affairs Ed Derwinski, updated the 1951 U.S.–Iceland treaty, adding an explicit exemption of the Cargo Preference Act, guaranteeing 35% of the contract would go to Icelandic companies, and giving Icelandic companies an opportunity to compete for up to 65% of the contract."[16][18][19] At the time, Derwinski said, "If we don't solve this problem, then the U.S. will be in a cod war". The United States Senate ratified the treaty one day before Reagan left for Reykjavik to attend a summit meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev.[18] Reagan met with the President of Iceland, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, before seeing Gorbachev, giving his guarantee that the majority of the contract would be returned to Icelandic shipping companies.[18]

Though a tumultuous time, Rainbow Hope kept at least part of the Iceland route from 1987 through late 1990. In the 1987 bidding, Rainbow was the only U.S. company to bid.[16] Bids from Icelandic competitors were lower, giving them 65% of the carriage rights, while Rainbow Hope secured the remaining 35%.[16] In the 1988 bidding, the Navy changed the bidding process in a way Rainbow found unfair, and Rainbow took a new case to the Washington D.C. District Court.[16] By May 1988, the court had issued a preliminary injunction halting the bidding process and ordering carriage be continued under the terms of the 1987 contracts.[16] In November 1988, the court granted a summary judgement for Rainbow, finding the new bidding system illegal.[16] This judgement held for nearly two years, but was ultimately overturned on 24 August 1990, when a panel of Judges Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Douglas H. Ginsburg and David B. Sentelle of the U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C. Circuit, reversed the lower court's decision.[16]

Operational incidents[edit]

In addition to the almost non-stop succession of challenges related to the contracts on the U.S.–Iceland run, Rainbow Hope was involved in a few notable operational incidents. The most notable of these involves a labor strike that prevented Rainbow Hope from discharging cargo, keeping the vessel at anchor for 22 days.[22] The ship was scheduled to depart bound for Iceland on 24 September 1984, but the U.S. Government and Rainbow were aware there was the possibility of a strike by Icelandic longshoremen scheduled to begin on 4 October.[22] Rainbow Hope arrived at Njarðvík, Iceland on 8 October, while the strike was already underway.[22] Rainbow repeatedly contacted the U.S. government for instructions, but none were given.[22] The ship remained idle at anchor for 22 days unable to discharge its cargo.[22] The strike ended on 30 October, and the cargo was delivered the next day.[22] The government paid Rainbow $266,370.50 for the delivery, but Rainbow filed suit in the 3rd Circuit Court seeking remuneration for the extra 22 days of waiting.[22] The court denied the claim, and appeals lasted until 24 June 1991, when the appeals court upheld the earlier decision.[22]

Other operational incidents of note include a 1988 fire during a return voyage from Iceland to the United States which forced the ship to stop in Newfoundland for repairs, and a crane breakdown on 15 November 1991 during cargo operations that required repairs be made in Praia da Vitória, Azores.[23][24]

Juno[edit]

The ship's certificate of inspection was deactivated by the United States Coast Guard on 9 May 1994, rendering it unable to move.[25] On 28 March 1996, the vessel had been sold to "owners in Jamaica" and the Coast Guard prevented the ship from receiving oil and proceeding from its berth until a valid certificate of financial responsibility could be provided.[26]

In late 1996, the ship was purchased by the company Noro of Haugesund, Norway under a 6,000,000 Norwegian krone (approximately $800,000 in 1998 U.S. dollars) mortgage by Sparebank 1 SR-Bank.[27] On 31 December 1996, the new owner registered the ship under the Norwegian International Ship Register and wages for the journey to Norway were guaranteed by Sparebanken Rogaland.[27] The ship was inspected in Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 22 April 1997.[28] On 30 June 1998 it was transferred to the Norwegian Ship Register.[27] It was spotted by amateur enthusiasts in Haugesund on 26 October 1998.[29] On 12 January 1999, the ship was renamed Juno.[30] On 17 November 1999, the ship was declared free of financial encumbrances and sold to the American company TransAtlantic Lines.[31]

Geysir[edit]

In 1997, Gudmundur Kjærnested decided to start a shipping company to serve the Iceland route.[32] Then an Icelandic citizen, educated in the United States, and having worked at Van Ommeren shipping for seven years, he was familiar with the route and its history.[32] Kjærnested's college roommate at Babson College, Brandon C. Rose, came from an affluent family whose yearly business revenues were estimated at $200 million per year.[32] Rose offered to back the company, and together they started the two companies TransAtlantic Lines LLC and TransAtlantic Lines Iceland in February 1998.[32] The two were originally even partners in both ventures.[32] Shortly thereafter, they accepted an offer from shipping company American Automar to purchase 51% of the company, along with a never-exercised option to buy 51% of another Icelandic company largely owned by Kjærnested, Atlantsskip.[32]

The company made several preparations to bid for the Iceland contract. Rose secured a million-dollar letter of credit from the State Bank of Long Island to back early operations.[33] The company did not yet own any ships, but did secure four letters from U.S. shipping companies pledging to supply vessels sufficient to cover the charter requirements.[33] One of the pledged vessels was the supply boat Native Dancer.[33]

Eight bids for the 1998 U.S.–Iceland run were solicited by the Military Traffic Management Command on 30 January 1998, and six bids were received.[34] Observers speculate that the bids were from the Icelandic company Eimskip, Dutch shipping company Van Ommeren, Atlantsskip, TransAtlantic Lines, and TransAtlantic Lines Iceland.[32] In September 1998, the Military Traffic Management Command awarded 65% of the Iceland contract to TransAtlantic Lines Iceland, the lowest overall bidder, and the remaining 35% to the TransAtlantic Lines LLC, the lowest bidder among American shipping companies.[33][34] The portion awarded to TransAtlantic Lines LLC had a cumulative total value of $5,519,295 and was set to expire by 31 October 2000.[34]

Within a month, TransAtlantic re-flagged Juno to the United States and renamed it Geysir at the Port of Jacksonville.[35] In response to the awards, the government of Iceland lodged a protest with the U.S. State Department, arguing that "TLI was not a true Icelandic shipping company" and "lacks the necessary experience, technical capability, financial responsibility, and material connection with Iceland"[33] Shipping companies Van Ommeren Lines (USA) and Eimskip of Iceland, which had previously serviced the Iceland route, sued the United States protesting the award.[33] The district court found for Van Ommeren and Eimskip, requiring the Army to restart the bidding process.[33] TransAtlantic appealed the decision, and on 11 January 2000 the Court of Appeals reversed the lower court's decision, finally securing the contract for TransAtlantic.[33]

On 4 December 2000, members of the Coast Guard Marine Safety Office observed an accidental discharge of approximately 250 US gallons (950 L) of diesel fuel from one of Geysir's tank vents into the Elizabeth River.[36] In 2001, the Coast Guard of Iceland detained the vessel leading the American Bureau of Shipping to temporarily revoke the ship's safety construction certificate and safety equipment certificate.[37]

On 8 September 2006, with the Cold War well over, the United States ceremonially disestablished Naval Air Station Keflavik and its twenty-three tenant commands, a process begun that March.[38] The closure marked the end of the 65-year military presence, the last 45 years of which coordinated under the United States Navy with activities of the National Guard, Air Force, and Army.[38][39]

On 3 February 2009 the United States Transportation Command awarded TransAtlantic a $15,078,334 contract to carry cargo between the United States and the terminal in Praia da Vitoria, Azores.[40] This contract, serviced by the Geysir, is expected to be completed by 29 February 2012, and was a 100 percent Small Business Set Aside acquisition with two bids received.[40]

As of 2010[update], the ship is owned and operated by TransAtlantic Lines LLC. The company currently owns and operates 5 vessels, including one tug-and-barge combination. Four of these vessels are chartered by the Military Sealift Command, and perform duties such as delivering cargo to U.S. military activities in Diego Garcia and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. TransAtlantic Lines has no collective bargaining agreements with seagoing unions.[41]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Equasis, 2010, Ship info page.

- ^ a b c d e f g h American Bureau of Shipping 2010, General Characteristics page.

- ^ United States Coast Guard PSIX, 2010.

- ^ For The Mouse that Roared comparison and Elizabeth Dole's involvement, see Michael, Killian (1986-09-24). "Shultz Signing Iceland Pact To Soothe Mouse That Roared". Chicago Tribune. Chicago: Tribune Company. For Antonin Scalia and Kenneth Starr, see U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C., 1986. For Ronald Reagan and George Shultz, see Eichenwald 1987, p.2. For Ruth Bader Ginsburg, see U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C., 1986.

- ^ a b c d American Bureau of Shipping 2010, Hull page.

- ^ a b American Bureau of Shipping 2010, Capacity page.

- ^ American Bureau of Shipping 2010, Lifting Equipment page.

- ^ a b American Bureau of Shipping 2010, Machinery page

- ^ "Seatrade". 9. Colchester, England: Seatrade Publications. May 1979.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Marine Engineering log". 86. New York: Simmons-Boardman. 1981.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The motor ship". 61. London: Temple Press Ltd. 1980.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The federal Title XI program is part of the Merchant Marine Act of 1936. It provides federal guarantees to American customers of American shipbuilders. The government does not finance construction of these ships directly; rather, it guarantees repayments of loans issued by independent banks. The program is administered by the United States Maritime Administration.

- ^ "Traffic World". 205. Chicago: Traffic Service Corporation. 1986.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d U.S. Court of Appeals, 1986, p.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eichenwald 1987, p.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C., 1990.

- ^ a b c d e f g h U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C., 1986.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eichenwald 1987, p.2.

- ^ a b c Michael, Killian (1986-09-24). "Shultz Signing Iceland Pact To Soothe Mouse That Roared". Chicago Tribune. Chicago: Tribune Company.

- ^ United States Court of Appeals, Washington D.C. District, 1986.

- ^ U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C., 1990. Text of the treaty is available at 1986 Treaty Between the United States of America and the Republic of Iceland to Facilitate Their Defense Relationship.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 3rd U.S. Circuit Court, 1991.

- ^ U.S. International Trade Commission (1990-06-26). "HQ 110849". Rulings And Harmonized Tariff Schedule. Washington, DC: U.S. Government.

- ^ U.S. International Trade Commission (1993-05-26). "HQ 112665". Rulings And Harmonized Tariff Schedule. Washington, DC: U.S. Government.

- ^ U.S.C.G. 2001, case number MI94018576.

- ^ U.S.C.G. 2001, case number MV96002382.

- ^ a b c Norwegian International Ship Register, 2010.

- ^ U.S.C.G. 2001, case number PS97021194.

- ^ Brian-Davis, Edward (2010). "Rainbow Hope". ShipPhotos. ShipPhotos.co.uk. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ Norwegian Ship Register, 2010a.

- ^ Norwegian Ship Register, 2010b.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Hefur inntak flutningasamningsins verið hunsað?" [Has input been ignored in the carriage contract?]. Morgunblaðið (in Icelandic). Reykjavík. 6 May 2000. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- ^ a b c d e f g h District of Columbia Circuit Court, 2000.

- ^ a b c Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs), 1998.

- ^ U.S.C.G. 2001, case number MI99036165.

- ^ U.S.C.G. 2001, case number MV00004567.

- ^ U.S.C.G. 2001, case number MI01015269.

- ^ a b Naval Media Center Broadcasting Detachment Keflavik (2006-09-09). "Naval Air Station Keflavik Disestablishes After 45 Years". Washington D.C.: United States Navy. Archived from the original on September 6, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (2006-09-29). "Last U.S. Service Members to Leave Iceland Sept. 30". Washington D.C.: United States Navy. Archived from the original on September 6, 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ^ a b Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs), 2009.

- ^ American Maritime Officers (November 2004). "Non-union operator wins charter held by Sagamore". AMO Currents. Archived from the original on 2006-07-20. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

References[edit]

- "Geysir (8004244)". ABS Record. American Bureau of Shipping. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) (1998-09-16). "Contracts for Wednesday September 16, 1998". Contracts. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) (2009-02-03). "Contracts for Tuesday February 03, 2009". Contracts. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- Carelli, Richard (2000-05-15). "U.S.-Iceland shipping dispute sidestepped by Supreme Court". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- Eichenwald, Kurt (5 April 1987). "How One-Ship Fleet Altered U.S. Treaty". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- "Geysir (7710733)". Equasis. Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Norwegian International Ship Register (2010a). "Rainbow Hope". Norwegian Ship Registers. Bergen, Norway: Norwegian International Ship Register.. On the search page, set type to "Historical", IMO number to "7710733", register to "All" and status vessel to "All (active and deleted)".

- Norwegian International Ship Register (2010b). "Juno". Norwegian Ship Registers. Bergen, Norway: Norwegian International Ship Register.. On the search page, set type to "Historical", IMO number to "7710733", register to "All" and status vessel to "All (active and deleted)".

- Norwegian Ship Register (2010). "Rainbow Hope". Norwegian Ship Registers. Bergen, Norway: Norsk Ordinært Skipsregister.. On the search page, set type to "Historical", IMO number to "7710733", register to "All" and status vessel to "All (active and deleted)".

- Rainbow Navigation, Inc., et al. v. Department of the Navy, et al., 783 F.2d 1072 (U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C. 14 February 1986).

- Rainbow Navigation, Inc., et al. v. Department of the Navy, 911 F.2d 797 (U.S. Court of Appeals, Washington D.C. 24 August 1990).

- The Iceland Steamship Company, Ltd.-eimskip and Van Ommeren Shipping (usa) Llc, Appellees v. the United States Department of the Army and Louis Caldera, Secretary of the Army, Appellees Transatlantic Lines-iceland Ehf. and Trans Atlantic Lines, L.l.c., Appellants, 201 F.3d 451 (District of Columbia Circuit Court 11 January 2000).

- Rainbow Navigation, Inc., et al. v. United States of America, 937 F.2d 105 (Third U.S. Circuit Court 24 June 1991).

- "Geysir (51544)". Port State Information Exchange. United States Coast Guard. Retrieved 2013-05-20.

- United States Coast Guard (2001). "MV Geysir". PSIX Archive Database. Washington, D.C.: United States Coast Guard.

External links[edit]

| External images | |

|---|---|

- TransAtlantic Lines LLC Company Profile at Det Norske Veritas

- Ships owned record at American Bureau of Shipping

- 2009 Contract award Archived 2010-12-20 at the Wayback Machine