Livre des merveilles (BNF Fr2810)

Livre des merveilles du monde (BnF Fr2810) is an illuminated manuscript made in France around 1410–1412. It is a collection of several texts concerning commercial, religious, and diplomatic contact between Europe and Asia. The authors of these texts include Marco Polo, Odoric of Pordenone, Wilhelm von Boldensele, Uzbeg, Benedict XII, John Mandeville, Hayton of Corycus, Riccoldo da Monte di Croce, and others. The manuscript contains 297 folios and 265 miniatures. It has a long history of being owned by prominent French figures and families. It is currently kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

History[edit]

The manuscript was made in France around 1410–1412.[1] It contains 297 folios and 265 miniatures produced by several Parisian workshops, thought to be those of the Mazarine Master, Boucicaut Master, and Bedford Master.

The first owner of the manuscript was John the Fearless, evidenced by his coat of arms, marginal notes, and other identifying symbols appearing throughout the text.[1]

Later, in 1413, John the Fearless gifted the manuscript to his uncle John, Duke of Berry, whose coat of arms appears on Folios 1, 97, 136v, 226, and 268. Inventories in 1413 and 1416 of the Duke of Berry's personal library confirm that the manuscript remained in his possession until his death.[1]

Upon the Duke of Berry's death, the manuscript was transferred to the Armagnac family by way of his daughter Bonne of Berry's marriage to Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac. The Armagnac coat of arms adorns Folios 1, 116, 136v, 141, 226, and 228.[1]

Eventually, Jacques d'Armagnac, the grandson of the Duke of Berry, owned the manuscript, evidenced by marginal notes on Folio 299v. In 1476, Jacques was arrested by the son-in-law of King Louis XI of France, resulting in the dissolution of the Armagnac library and the manuscript's disappearance from record, for a time.[1]

The next recorded ownership of the manuscript is from an inventory of the library of Charles de Valois, Duke of Angoulême, which mentions a similarly titled possession. The manuscript thus potentially became part of the personal library of King Francis I of France, Charles' son. Later inventories in the sixteenth century confirm the transference of the manuscript to the Librairie royale de Fontainebleau.[1]

In 1622, Nicolas Rigualt performed an inventory of the royal library, recording the manuscript is still there. Subsequent inventories in 1645 and 1682 confirm the library's continued ownership.[1]

As of 2022[update], the manuscript is housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[1]

Contents[edit]

Texts[edit]

The contents are as follows:[1]

- Marco Polo's Livre des Merveilles (Devisement du monde, Description of the World) outlines the explorer's journeys through the Mongol Empire along the Silk Road, cataloging firsthand experiences with various cultures.

- Odoric of Pordenone's Itinerarium de mirabilibus orientalium Tartarorum

- Wilhelm von Boldensele's Liber de quibusdam ultramarinis partibus et praecipue de Terra sancta

- correspondence between Pope Benedict XII and Uzbeg Khan

- correspondence between Benedict XII and Beijing Christians

- an overview of the Yuan government

- John Mandeville's Voyages, a potentially fabricated account of additional explorations.

- Hayton of Corycus's Fleur des estoires de la terre d’Orient, record of histories of the Orient.

- the Liber peregrinationis (Book of the Sojourn Abroad) by Riccoldo da Monte di Croce

Most of the texts are French translations of earlier texts. Jean de Long served as the primary translator. Earlier editions of Marco Polo's Description of the World date as early as 1298.[2] John Mandeville's text dates to as early as c.1356-7.[2] The texts describe a variety of cross-cultural interactions in the medieval world.

Illuminations[edit]

Folio 12r, or The Magi Worshiping Fire, part of Marco Polo's Description of the World, showcases a scene of the Adoration by the Three Magi, albeit with key differences from the traditional Christian imagery. The image originates from Polo's text, describing Marco Polo's encounter with the city of Saba, which Polo noted claimed to be the burial site of the Three Magi. In the miniature, the Three Magi are seated in prayer, focusing their attentions on flames mounted on a pedestal. The fire represents a localized version of the Adoration, in which the Three Magi were Persian kings who, after witnessing Christ in multiple forms including that of the Christ child, received a box with a stone inside. While the three kings were confused by the gift, the stone burst into flames. The kings then realized the stone was a gift from God and brought it to the local community in Saba, who worshipped the fire as a divine present. Art historian Mark Cruse notes the importance of this folio as indicating a willingness to engage with other culture's beliefs; the artists chose to represent the local story directly as it was told instead of imposing the traditional European telling beside the text.[3] Still, some may argue the image is just traditional orientalism, images of exotic creatures to depict non-Western cultures.[4] Additionally, this folio is an example of the circulation of ideas in the medieval world, as it shows a European story of travelling, adapting, and returning in a new form.

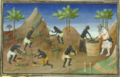

Folio 45r, or The Khan's Money Exchange, shows a scene of trade between a seated khan and three men. The text on the same page, from Marco Polo's Description of the World, describes the novelty of the khan's paper money, noting that traders from far-off locales bring their wares in exchange for these slips of paper. The three men in the image serve as an example of this widespread interest, their hats and clothing suggesting they belong to different cultures. The inspiration for these figure's clothing could have originated from artistic contact between Europe and Asia but most likely originated from Italian art depictions of "Eastern" figures.[3] In either case, this folio serves as record of cross-continental trade.

Folio 226r depicts the first owner of the manuscript, John the Fearless. The illuminators of the manuscript superimposed John over the figure of Pope Clement V, surrounding him with a variety of symbols.[1] The Duke of Burgundy's coat of arms adorns the cloth on which he sits as well as the tympanum, or semi-circular panel below the arch, of the building. Additional symbols of the Duke are situated in the image: the hop leaf, level, and planer can be found along the top left and right corners of the image in addition to being featured on the chain lining the Duke's shoulders. Two animals within the image indicate further connections. The lion, located in the bottom left corner of the image, represents a connection to the historical region of French Flanders. The eagle, located in the bottom right corner of the image, represents John the Apostle, whom the Duke often associated himself with. Visual indicators like these serve as records for historians about the owners of these manuscripts and the images of themselves they tried to project to the world.

Gallery[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j de Becdelièvre, Véronique (2019) [2011]. "Archives et Manuscrits: Français 2810". Bibliotheque nationale de France. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ a b Gaunt, Simon (September 1, 2009). "Translating the Diversity of the Middle Ages: Marco Polo and John Mandeville as "French" Writers". Australian Journal of French Studies. 46 (3): 237–238. doi:10.3828/AJFS.46.3.235.

- ^ a b Cruse, Mark (2019). "Novelty and Diversity in Illustrations of Marco Polo's Description of the World". In Keene, Bryan C. (ed.). Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts. Getty Publications. pp. 195–202. ISBN 9781606065983.

- ^ Wittkower, Rudolf (1942). "Marvels of the East: A Study in the History of Monsters". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 5. The Warburg Institute: 159–197. doi:10.2307/750452. JSTOR 750452. S2CID 192371707.

Further reading[edit]

- Meiss, Millard. French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry: The Boucicaut Master. Phaidon, 1968.

- Wittkower, R. “Marco Polo and the Pictorial Tradition of the Marvels of the East.” Oriente poliano: studi e conferenze tenute all’Is.M.E.O in occasione del VII centenario della nascita di Marco Polo. Rome: Istituto italiano per il medio ed estremo oriente, 1957.

- Rouse, R.H. and M.A Rouse. “The Commercial Production of Manuscript Books in Late-Thirteenth Century and Early-Fourteenth Century Paris.” In Medieval Book Production: Assessing the Evidence, Proceedings of the Second Conference of the Seminar in the History of the Book to 1500. Ed. L. Brownrigg. Anderson-Lovelace: Red Gull Press, 1990.