Living Venus

| Living Venus | |

|---|---|

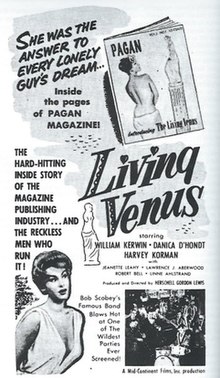

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Herschell Gordon Lewis[1] |

| Screenplay by | James McGinn Seymour Zolotareff Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Story by | James McGinn |

| Produced by | Herschell Gordon Lewis David F. Friedman Lewis Preston Collins |

| Starring | William Kerwin Harvey Korman Danica d'Hondt |

| Narrated by | Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Cinematography | Arthur Haug |

| Edited by | E.K. Hathorn |

| Music by | Martin Rubenstein |

Production companies | Mid-Continent Films, Inc. |

| Distributed by | State Rights |

Release date | February 1961 |

Running time | 74 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Living Venus is a 1961 exploitation film loosely based on the life of Playboy magazine founder Hugh Hefner. Marking the directorial debut of Herschell Gordon Lewis, the film stars frequent Lewis collaborators William Kerwin as unscrupulous magazine editor John V. Norwall and Harvey Korman as photographer Ken Carter.[2][3][4]

Plot[edit]

John V. Norwall, editor of Newlywed magazine, enlists up-and-coming photographer Ken Carter to shoot a cover for the periodical. The resulting image of a couple being chased by a gunman angers the magazine's publisher, who fires John. The disgraced editor resolves to establish his own magazine, Pagan, where he can enjoy greater editorial freedom.

At home, John rebuffs his fiancée Diane after she insists that the couple be married immediately. He then drunkenly steals a Venus de Milo statuette from an antique shop, hoping to use it as inspiration for his new magazine. John notes the resemblance between his statuette and Peggy Brandon, his waitress at a bar, and invites her to model for his magazine as "The Living Venus". He and Ken take softcore erotic photographs of Peggy and use these images in attempt to attract investors to the new publication. When they are unsuccessful, they pawn off Ken's camera to purchase a new typewriter. The two secure additional funding from Max Stein, a publisher with a shady reputation, and are granted further financing upon the success of the magazine's first issue.

As John is getting Pagan off the ground, he receives a call from Diane, imploring him to come to the wedding that she has planned for that weekend. When he fails to appear, Diane and her father confront John at his apartment, resulting in an altercation between the two men. John attempts to begin an affair with Peggy, who is also being pursued by Ken. When Peggy informs him that Ken has proposed to her, John offers his own marriage proposal and hires photographer Geoffrey Page to replace Ken at the magazine. John persuades Peggy to retire from modelling and serve Pagan as a “promotions manager”, seducing clients into buying advertising. Peggy is reluctant to perform this role and soon becomes dependent on alcohol.

Pagan enjoys a period of commercial success until John and Geoff become more focused on romancing the models than running a magazine. Meanwhile, Ken finds success in his new career as a fashion photographer. A drunken Peggy encounters him during one of his shoots, and he assures her he will be there if she needs him. Embarrassed, Peggy runs away, eventually arriving at a tense Pagan staff meeting. When she confronts John, he slaps her and calls her an alcoholic.

Before the magazine's two-year anniversary party, Max announces that he will no longer finance the publication and suggests that John re-hire Ken. A sober Peggy arrives at the party, reaffirming her feelings for John. Upon rejection, she resorts to binge-drinking and ultimately drowns in a swimming pool. At her funeral, Max reveals that he has hired Ken to replace John, leaving the latter without any job or romantic prospects.[1][2]

Cast[edit]

- William Kerwin as Jack (John V. Norwall)

- Harvey Korman as Ken Carter

- Danica d'Hondt as Peggy Brandon

- Jeanette Leahy as Margo

- Lawrence J. Aberwood as Max Stein

- Linné Ahlstrand as Diane

- Robert Bell as Harry

- Lee Hauptman as Geoffrey Page

- Andrew Lindhoff as Diane's father

- Edward Meekin as Benson

- Herbert Graham as Jim

- Charles Cook as Client at pool

- Cherie Ross as Girl at bar

- Clio Vias as Lorraine (voice)

- Fran Harding as Lorraine's legs

- Adele Kelly, Fred Knapp, and John Perak as editorial staff

- Billy Falbo as Comedian at party

- Bob Scobey as himself

- Nancy Downey as The 'Other Woman' (uncredited)

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

The script of Living Venus was purchased half-finished from Jim McGinn and Seymour Zolotareff after the pair had worked on it for three weeks. Herschell Gordon Lewis believed that their screenplay had more thematic substance than that of his previous work. According to Lewis, despite the scenes featuring nude actresses, the film "was not planned as a nudie" but rather an exploration of how one man's ego affects his career in the publishing industry.[5]

Pre-production[edit]

Casting[edit]

Lewis enlisted William Kerwin and Harvey Korman for the roles of John Norwall and Ken Carter, respectively. The director had previously worked with the pair on Carving Magic, a 1959 promotional short for Swift & Company.[6] Living Venus is one of two Lewis projects with a cast composed of Screen Actors Guild members. As a result, the film features more professional talent than his later films; Korman, Billy Falbo, and Karen Black would eventually garner greater recognition in the motion picture industry.[5]

Filming[edit]

Living Venus was shot in Chicago, Illinois. Because of his background as an industrial filmmaker, Lewis experienced frustration with what he described as "foot draggers" rampant in the union crew. Lewis employed a non-union workforce on subsequent projects.

Lewis cut a nude scene involving Karen Black, who played a small, uncredited role in the movie, at her manager's request. The director later complained that Black's attitude contributed to production delays that were disproportionate to her screen time in the finished picture.[5]

Post-production[edit]

Music[edit]

The film's score was composed by Martin Rubenstein. Bob Scobey, credited in certain promotional materials as Bob Scobie, contributed original music featured in the party scene. Harold Lawson composed the words and music to the song "Living Venus", which was performed by Robert Bell.[1]

Release and reception[edit]

Living Venus was released in February 1961, only months after Lewis’s previous project The Prime Time, which he produced but did not direct. The combined box office failures of the two pictures resulted in significant financial losses for Modern Film Distributors, who subsequently defaulted on their agreement with Mid-Continent Films, Lewis' production company.[5]

Home media[edit]

In 1990, Living Venus was released on home video as part of "The Sleaziest Movies in the History of the World", a series of films directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis and others with commentary from horror host Joe Bob Briggs.[7]

Music from the film is featured on The Eye Popping Sounds of Herschell Gordon Lewis, a compilation album of music from the director's filmography released by Birdman Records in 2002.[8]

In popular culture[edit]

Living Venus, along with several other Lewis titles, is featured in Domonic Paris' Film House Fever (1986), starring Steve Buscemi.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c n.a. "Living Venus". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ a b n.a. "Living Venus". Strange Vice. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ n.a. "Living Venus". IMDb. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ n.a. "Living Venus (1961) directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis". Letterboxd. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d Palmer, Randy (2000). Herschell Gordon Lewis, Godfather of Gore: The Films. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7864-2850-2. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ n.a. "Carving Magic (Short 1959)". IMDb. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ n.a. "THE SLEAZIEST MOVIES IN THE HISTORY OF THE WORLD". Slaughter Films. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Leone, Dominique. "The Eye Popping Sounds of...Herschell Gordon Lewis". Pitchfork. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ n.a. "Film House Fever - Connections". IMDb. Retrieved 1 June 2022.