Le loup-garou

| Le loup-garou | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Louise Bertin | |

Title page of the published libretto of Le loup-garou (Paris: Bezou, 1827) | |

| Translation | The Werewolf |

| Librettist | |

| Language | French |

| Premiere | 10 March 1827 |

Le loup-garou (The Werewolf) is a 19th Century opéra comique in one act in French with music by Louise Bertin and a libretto by Eugène Scribe and Jacques Féréol Mazas.[1] The work is a comedy inspired by the fairy tale of "Beauty and the Beast."[2] It was first performed on March 10, 1827 by the Opéra-Comique in Paris.[3]

The opera was the second of Bertin's four operas and the first to be performed publicly.[4][5] Scribe was a prolific writer, working on over one-hundred operas, most notably collaborating with Daniel Auber on thirty-nine operas. Mazas was a violinist and composer who later ran two theatre companies.

Plot[edit]

In a village in Burgundy in the Fifteenth Century, Alice's guardian Raimbaud has arranged for her to marry the falconer Bertrand. Raimbaud works for the Comte Albéric, who has been exiled by the king until he finds a woman who loves him for himself and not his title and wealth. Alice confides to her friend Catherine that she does not love Bertrand but instead loves a stranger, who saved her from drowning in the woods. Alice knows the stranger as "Hubert." Catherine, a young noble-woman, who loves Bertrand, wants Alice to break the engagement. Bertrand, who is superstitious, believes the wolf terrorizing the village is actually a werewolf. When thirteen arrive for dinner, Bertrand is spooked by the number; Catherine goes to find another to join them and returns with Hubert. Raimbaud recognizes "Hubert" is really Albéric. Bertrand thinks Hubert is the werewolf. Alice becomes convinced of this too and rejects Hubert. Catherine then agrees to marry him. Bertrand tells Alice he was enamored with Catherine but felt he was beneath her station. Bertrand and the villagers go to kill the wolf. Hubert appears and Alice fears that he will turn into a werewolf and be killed. Alice tells Hubert she loves him, even if he is a werewolf. Bertrand and the villagers return, having killed the wolf and are surprised to see Hubert alive. Raimbaud reveals Hubert is really the Comte Albéric. Catherine announces her engagement to Bertrand and Alice her betrothal to Albéric.[6][7][8]

19th Century[edit]

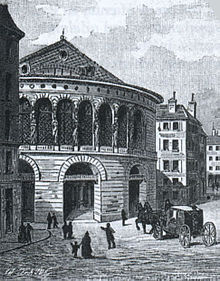

Le loup-garou was premiered March 10, 1827 by the Opéra-Comique at the Salle Feydeau in Paris.[9][10] The first performance was given as a charity benefit for victims of the winter of 1827.[11]

The original cast was Jean-Baptiste Chollet as the Comte Albéric, M. Valère as Raimbaud, Augustin Vizentini as Bertrand, Geneviève-Aimé-Zoë Prévost as Alice, and Marie-Julie Boulanger as Catherine.[12] The leads, Chollet and Prévost, were married in real life and had a daughter who also became an opera singer.[13][14]

The opera was "brilliantly successful."[15][16] It received twenty-six performances.[17] Le loup-garou was given in October 1827 in Rouen at the Théâtre des Arts.[18] The libretto and score were both published the year of the premiere.[19][20]

The leading Parisian newspaper Journal des débats (which was owned by the composer's father, Louis-François Bertin) wrote that the audience at the first two performances "laughed a lot" and found the music to be graceful, fresh, and original, executed by "the perfect ensemble" of singers. [21] Le Figaro called the plot "implausible and ridiculous" and said the music was "weak and lacks color."[22] The Revue musicale said the audience at the first performance was so rowdy that the opera could not be judged properly; but at the second, the work was a "complete success" which received "lively applause."[23] The opera "gives hope because it is a work of originality."[24] Le Constitutionnel called the opera "pleasant, piquant, witty."[25]

A critic wrote of the music in 2022:

There is a long and pleasant overture . . . The melodies are gracious and even memorable . . . for the most part fairly simple. The vocal lines are unadorned compared to the contemporary music of Rossini or even composers like Hérold and Auber. There is no doubt, however, that Bertin knew her stuff; the ensembles are clever and well developed. Rossini knew Bertin and she certainly knew many of his operas, but with a couple of exceptions this work does not sound much like Rossini even though the structures can be compared to his short one-act works, most written early in his career . . . Bertin, however, has her own voice, her “sound,” in the plaintive Romance and elsewhere. It might have been a “sound” that was in a stage of development in 1827 when she was only 22, but it is hers.[26]

21st Century[edit]

After "a century-long oblivion," Opera Southwest in September 2022 performed Le loup-garou in the outdoor theatre at the Albuquerque Museum of Art and History in Albuquerque, New Mexico.[27][28] This was the American premiere and the first staging of the original work since the 19th Century.[29] Denise Boneau, who wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on Bertin, translated the libretto for the production.[30] The cast was Michael Rodriguez as the Comte Albéric, Miguel Pedroza as Raimbaud, Thomas Drew as Bertrand, Yejin Lee as Alice, and Mélanie Ashkar as Catherine.[31]

The first British production of Le loup-garou was given in London by Gothic Opera in October and November 2022 at the Round Chapel in Lower Clapton, Hackney.[32] Gothic presented Bertin's opera on a double-bill with Pauline Viardot's The Last Sorcerer.[33] The cast was Matthew Scott Clark as the Comte Albéric, Ashley Mercer as Raimbaud, Andrew Rawlings as Bertrand, Alice Usher as Alice, and Charlotte Hoather as Catherine.[34]

The overture from Le loup-garou was to be played by the Paris Chamber Orchestra at Paris's Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on June 23, 2023; three days before, Bertin's third opera Fausto was to be presented in a concert version at the same venue.[35][36]

The WholeTone Opera in October 2017 presented an adaptation of the work, The Werewolf: A Freshly Transformed, Fiercely Queer Opera, at The Rockwell in Somerville, Massachusetts.[37] The "modernized libretto" of this version was by J. Deschene and Teri Kowiak with new music by Molly Preston.[38] Nora Maynard, artistic director of the company, said "once we pared it down to its skeleton, we also found some excellent, lyrical vocal and orchestral writing to lay our new story upon," one where "almost all of the main characters in this story identify as queer or gay."[39] One review said the "apparent attempt at an edgy, risky operatic equivalent of The Rocky Horror Picture Show misjudged badly."[40]

References[edit]

- ^ McVicker, Mary (2016). Women Opera Composers: Biographies from the 1500s to the 21st Century. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 9781476623610.

- ^ Kriff, Jean (2019). "Romantique(s) Melpomène(s)". Humanisme (in French) (324): 96–101. doi:10.3917/huma.324.0096. LCCN 80647889. OCLC 6802347. S2CID 241261671. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

une version nouvelle de La Belle et la Bête

- ^ Letellier, Robert Ignatius (2010). Opéra-Comique, A Sourcebook. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. p. 35. ISBN 9781443821681.

- ^ McVicker, Mary (2016). Women Opera Composers: Biographies from the 1500s to the 21st Century. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 32. ISBN 9781476623610.

- ^ Elson, Arthur (1903). Woman's Work in Music, Being an Account of Her Influence on the Art, in Ancient as Well as Modern Times; a Summary of Her Musical Compositions, in the Different Countries of the Civilized World; and an Estimate of Their Rank in Comparison with Those of Men. Boston: Page. p. 183. OCLC 6930212.

- ^ Moulin, Victor (1862). Scribe et son théâtre: études sur la comédie au XIXe siècle (in French). Paris: Tresse. p. 64. OCLC 12167235.

- ^ "Le loup garou". Opera Southwest. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Hoather, Charlotte (October 2, 2022). "Gothic Opera–Le Loup-Garou". Charlotte Hoather, Soprano. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Letellier, Robert Ignatius (2010). Opéra-Comique, A Sourcebook. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. p. 35. ISBN 9781443821681.

- ^ Fétis, François-Joseph (1868). Biographie universelle des musiciens et bibliographie générale de la musique (in French). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Paris: Firmin Didot Frères. p. 284. OCLC 5845494.

- ^ Landowski, W.-L. (November 16, 1936). "À propos du centenaire de La Esmeralda". Le Ménestrel: Journal de musique (in French). 98 (46). Paris: 313-314. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ Bertin, Louise; Scribe, Eugène; Mazas, Jacques Féréol (1827). Le loup-garou, opéra-comique en un acte (in French). Paris: Bezou. p. 2. OCLC 24105214.

- ^ Auber, Daniel-François-Esprit (2019). Letellier, Robert Ignatius (ed.). Daniel-François-Esprit Auber's Les Chaperons blancs. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. p. xviii. ISBN 9781527535794.

- ^ White, Kimberly (2018). Female Singers on the French Stage, 1830–1848. Cambridge Studies in Opera. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108688475.

- ^ "The Public Are Respectfully Informed". Galignani's Messenger. No. 3944. Paris. September 22, 1827. p. 4. OCLC 02261397. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Hoefer, Jean Chrétien Ferdinand Andrew, ed. (1855). Nouvelle biographie générale depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours, avec les renseignements bibliographiques et l'indication des sources à consulter (in French). Vol. 5. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères. p. 739. LCCN 02003498.

- ^ Dalzon, Christian (2022). "Search and Rescue Effort Continues in ABQ". ConcertoNet.com, The Classical Music Network. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Élart, Joanne (2004). Catalogue des fonds musicaux conservés en Haute-Normandie: Bibliothèque municipale de Rouen (in French). Vol. 1. Rouen: Publications de l'université de Rouen. p. 460. ISBN 9782877753333.

- ^ Bertin, Louise; Scribe, Eugène; Mazas, Jacques Féréol (1827). Le loup-garou, opéra-comique en un acte (in French). Paris: Bezou. OCLC 24105214.

- ^ Levy, Jean (1879). Catalogue de la bibliothèque de la ville de Lille, Sciences et Arts (in French). Lille: Lefebvre-Ducrocq. p. 741. OCLC 493365161.

- ^ "Théatre royal de l'Opéra Comique". Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (in French). Paris. March 14, 1827. pp. 1–2. OCLC 93021694. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Opéra-Comique: Deuxième represéntation de le Loup-Garou, opéra-comique en 1 acte". Le Figaro (in French). Vol. 2, no. 59. Paris. March 14, 1827. p. 231. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Théatre de Opéra-Comique". Revue musicale (in French). Vol. 1, no. 5. Paris: François-Joseph Fétis. March 1827. pp. 144–46. OCLC 10031603. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Théatre de Opéra-Comique". Revue musicale (in French). Vol. 1, no. 5. Paris: François-Joseph Fétis. March 1827. pp. 144–46. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ "Spectacles: Théatre Royal de l'Opéra-Comique: Le Loup-Garou, opéra en un acte". Le Constitutionnel (in French). No. 71. Paris. March 12, 1827. p. 4. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ Jernigan, Charles (September 18, 2022). "Bertin's Le Loup Garou, Opera Southwest, Albuquerque, September 9-11, 2022". Donizetti Society. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Dalzon, Christian (2022). "Search and Rescue Effort Continues in ABQ". ConcertoNet.com, The Classical Music Network. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "Le loup-garou". Operabase. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "Le loup garou". Opera Southwest. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "Denise Boneau". Opéra-Comique. Retrieved May 27, 2003.

- ^ Dalzon, Christian (2022). "Search and Rescue Effort Continues in ABQ". ConcertoNet.com, The Classical Music Network. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Hoather, Charlotte (September 25, 2022). "Gothic Opera–Double Bill". Charlotte Hoather, Soprano. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "The Werewolf + The Last Sorcerer". Operabase. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Gothic Opera (2022). "The Werewolf + The Last Sorcerer". Gothic Opera. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ San Frax, Julien (April 22, 2023). "À la recherche des musiques perdues (In search of lost music)". Causeur (in French). Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ "Saison 22/23: Orchestre de chambre de Paris du 22 Septembre 2022 au 23 Juin 2023". Radio France (in French). August 4, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Salazar, Daniel (October 3, 2017). "WholeTone Opera's Presents LGBTQIA Opera for Halloween". OperaWire. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Simeonov, Jenna (October 14, 2017). "A "Fiercely Queer Opera" for Halloween". Schmopera.com. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Simeonov, Jenna (October 14, 2017). "A "Fiercely Queer Opera" for Halloween". Schmopera.com. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

- ^ Fuller, Rachel (October 28, 2017). "Celebrating Queerness Operatically". The Boston Musical Intelligencer. Retrieved May 27, 2023.

Further reading[edit]

- Boneau, Denise Lynn (1989). Louise Bertin and Opera in Paris in the 1820s and 1830s (Ph.D. (Music)). University of Chicago. OCLC 36041535.

- Crémades, Matéo (April 2013). Louise Bertin: Une compositrice sous Louis-Philippe (Louise Bertin: A composer under Louis-Phillipe). Les colloques de l’Opéra Comique: Les compositrices au siècle de Pauline Viardot (Conferences of the Opéra Comique: Composers in the Century of Pauline Viardot) (in French). Paris: l'Opéra Comique.