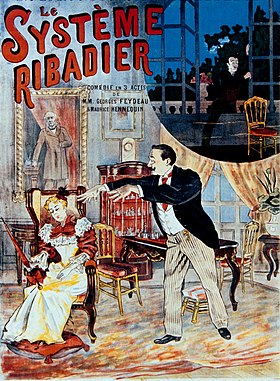

Le Système Ribadier

Le Système Ribadier (The Ribadier System) is a farce in three acts by Georges Feydeau and Maurice Hennequin, first performed in November 1892. It depicts a husband's stratagem for escaping the marital home to engage in extramarital intrigue, by hypnotising his wife.

Background and premiere[edit]

Earlier in 1892, Feydeau had emerged from a six-year spell in which his plays were failures or at best very modest successes. With Monsieur chasse! (Théâtre du Palais-Royal, 114 performances)[1] and Champignol malgré-lui (Théâtre des Nouveautés, 434 performances),[2] the latter co-written with Maurice Desvallières, he restored his reputation and fortune. To follow Monsieur chasse! at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal, he collaborated with Maurice Hennequin, son of a celebrated farceur of the previous generation, on Le Système Ribadier, which opened at the Palais-Royal on 30 November 1892, running for 78 performances.[3]

Original cast[edit]

- Ribadier – Paul Calvin

- Thommereux – Perrée Raimond

- Savinet – Milher[n 1]

- Gusman – Georges Hurteaux

- Angèle – Marie Magnier

- Sophie – Delphine Renot

Plot[edit]

Eugène Ribadier is the second husband of Angèle, the widow of M. Robineau. In the wake of her first husband's deceits (he deceived her 365 times in 8 years) Angele has developed an obsessive jealousy and she narrowly watches the activities of her second husband. Ribadier however possesses the gift of hypnotism – the eponymous system – and he profits from it by putting his wife to sleep at the time of his escapades. He wakes her on his return thanks to a trick he alone knows, until he unwisely reveals it to Aristide Thommereux, a friend who has returned from several years away in the East, hoping to renew his secret love for Angèle.[5]

While Ribadier is off on one of his escapades Thommereux uses the trick to wake Angèle to tell her again of his passion. She rejects him, but as he gets more insistent they hear a loud noise from below. It is Ribadier returning early, hotly pursued by Savinet, a wine merchant and husband of Ribadier's mistress. Thommereux escapes by the window and Angèle feigns a deep hypnotic sleep. She therefore overhears Ribadier admit his guilt to Savinet and bounds up furious as soon as the wine merchant departs.[6]

Ribadier tries various stratagems to recover his position including hypnotizing her again and trying to convince her she has dreamt what she heard. She however discovers the secret of the system and turns the tables by pretending that a lover has visited her every time she has been hypnotized. Thommereux thinks she means him, and abets Ribadier's outraged search for the unknown intruder. On the balcony they discover a button torn from a man's trousers. It turns out to belong to the amorous coachman Gusman who has been climbing up past the window to visit the maid Sophie. For a fee, Gusman readily admits that he has been climbing in to see a woman who received him eagerly; Ribadier and Thommereux are aghast and confront Angèle. Her denial convinces them, and Gusman relieves them all by telling them he was seeing Sophie and is dismissed with less than half his fee. Ribadier and Angèle are reconciled – Thommereux returns to the East disappointed.[7]

Reception[edit]

The critic of Le Figaro, Henry Fouquier, thought the play "perhaps the most solidly constructed and most ingeniously handled of all the pieces that M. Feydeau has given us", and said that Feydeau had embroidered a farcical construction with comedy and fantasy.[8] A comment piece in the same paper said, "I saw, from one end of the evening to the other, only radiant faces, pretty eyes wet with joyful tears, shoulders shaken by violent spasms, mouths wide with laughter, gloves spilt by clapping".[9] The Paris correspondent of the London paper The Era commented that although Feydeau's new piece did not rival Champignol malgré lui in exuberant fun, it was still a worthy successor to his other successful play of 1892, Monsieur chasse!, being "highly amusing, full of droll scenes". The critic added, "The house rang with laughter throughout the evening, and the curtain fell to the warmest applause. The piece, however, is flimsy, and its incidents are somewhat far-fetched in their absurdity".[10]

Revivals and adaptations[edit]

After Feydeau's death in 1921 his plays underwent years of neglect, until interest in them revived in the 1940s. Le Système Ribadier was revived in 1963 in a production directed by Jacques François. Les Archives du spectacle record 15 new productions in Paris and other French cities between then and 2020,[11] including a 2007 production at the Théâtre Montparnasse, which was filmed for television.[12]

The piece was successfully given in a German translation in Berlin in 1893.[13] An adaptation into English, His Little Dodge was presented in London in 1896 starring Weedon Grossmith, Fred Terry, Alfred Maltby and Ellis Jeffreys and running for 81 performances.[14] The same version was given in New York the following year by Edward E. Rice's company.[15] An adaptation as Monsieur Rebadier's System was given in the US in 1979 with Roderick Cook as Ribadier.[16] A 2009 version with the title Where There's a Will, was given on a British provincial tour under the direction of Peter Hall, to lukewarm reviews.[17] An adaptation called Every Last Trick toured in 2014, to better notices.[18]

Notes, references and sources[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Noël and Stoullig (1893), p. 234

- ^ Noël and Stoullig (1893), p. 278 and (1894), p. 410

- ^ Gidel, p. 144

- ^ "Milher", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 13 August 2020

- ^ Feydeau, pp. 65–84

- ^ Feydeau, pp. 85–103

- ^ Feydeau, pp. 104–117

- ^ Fouquier, Henry. " Lés Théâtres", Le Figaro, 1 December 1892, p. 3

- ^ "Le Soirée Théâtrale"], Le Figaro, 1 December 1892, p. 3

- ^ "The Drama in Paris", The Era, 3 December 1892, p. 8

- ^ "Le Système Ribadier", Les Archives du spectacle. Retrieved 14 August 2020

- ^ TV5 programme information 2008 TV5Monde. Retrieved 14 August 2020

- ^ "The Drama in Berlin", The Era, 18 November 1893, p. 8

- ^ Wearing, p. 607

- ^ "Among the Theatres", The Brooklyn Times, 23 November 1897, p. 3

- ^ Nelsen, John. "Entertainment: Checking the regionals", The Daily News, 11 December 1979, p. 47

- ^ Gardner, Lynn. "Where There's a Will", The Guardian, 17 February 2009; Maxwell, Dominic. "More volts needed to fire up the va-va-voom", The Times, 17 February 2009, p. 28; and Grimley Terry. "Farce with too much talk and not enough happening", The Birmingham Post, 26 February 2009 (subscription required)

- ^ Maxwell, Dominic. "Roll up for all the fun of the Feydeau", The Times, 1 May 2014, p. 11; Brennan, Clare. "Feydeau's farce gets a rough-and-ready makeover", The Observer, 27 April 2014; and Gray Christopher "Comic effect with Every Last Trick of the book", The Oxford Times, 24 April 2014 (subscription required)

Sources[edit]

- Feydeau, Georges (1948). Théâtre complet, II (in French). Paris: Du Belier. OCLC 1091012783.

- Gidel, Henry (1991). Georges Feydeau (in French). Paris: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-066280-4.

- Noël, Edouard; Edmond Stoullig (1893). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1892 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Noël, Edouard; Edmond Stoullig (1894). Les Annales du théâtre et de la musique, 1893 (in French). Paris: Charpentier. OCLC 172996346.

- Wearing, J. P. (1976). The London Stage, 1890–1899: A Calendar of Plays and Players. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. OCLC 1084852525.,