Joseph Palmer (American Revolutionary War general)

Joseph Palmer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 31, 1716 Shaugh Prior, Devonshire, England |

| Died | December 25, 1788 (aged 72) Dorchester, Massachusetts |

| Battles/wars | |

| Spouse(s) |

Mary Cranch

(m. 1746; died 1788) |

| Children | Elizabeth, Mary, and Joseph Pearse Palmer |

| Relations | Nathaniel Peabody (son-in-law), Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, and Sophia Amelia Peabody Hawthorne (granddaughters) |

Joseph Palmer (1716–1788) was an English-American general during the American Revolutionary War, beginning with the Siege of Boston and the Battle of Lexington. A Cambridge Committee of Safety member, he issued the Lexington Alarm dispatch for Israel Bissell to ride to warn that the war with Britain had begun. Palmer went on intelligence-gathering missions in Vermont and Rhode Island. George Washington issued letters of commendation to Palmer for his service.

Palmer made a fortune before the war, and lost it after the war. Due to the kindness of Abigail Adams, his wife Elizabeth and their daughters lived at her Old House (in Quincy, Massachusetts) after Palmer's death. Elizabeth died two years later. His son Joseph Pearse Palmer attended Harvard College, participated in the Boston Tea Party, and fought with his father during the war. Joseph Pearse Palmer and Elizabeth Hunt Palmer were the parents of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, and Sophia Amelia Peabody Hawthorne.

Early life and marriage[edit]

Palmer was born at Shaugh Prior, Devonshire, England, on March 31, 1716,[1] a son of John and Joan Palmer, née Pearse.[2] He married Mary Cranch in 1746[3][4] and emigrated to Massachusetts later that year with his brother-in-law Richard Cranch.[3]

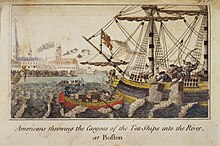

Palmer and Mary had two daughters, Mary (Polly) and Elizabeth.[5] Their son Joseph Pearse Palmer attended Harvard College.[4] He participated in the Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773).[6] Joseph tutored Elizabeth Hunt in history, geography, and arithmetic, meeting secretly. He courted her, and the couple eloped in 1772.[6] They first lived in Watertown and then Germantown. The Palmers had nine children, one of whom was Elizabeth Palmer, wife of Nathaniel Peabody and mother of Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Mary Tyler Peabody Mann, and Sophia Amelia Peabody Hawthorne.[4] Elizabeth taught her daughters the three Rs when they were young and read William Shakespeare to them.[4] Son Joseph was good friends with Royall Tyler, who lived with the Palmers in their Boston boardinghouse.[4]

Massachusetts Bay Colony[edit]

In 1752, Palmer and his brother-in-law built a glassworks in Germantown, now a part of Quincy, Massachusetts. Later, they built a chocolate mill and spermaceti and salt factories.[3] Palmer bought his brother-in-law's interests in the businesses by 1760.[4]

By the 1770s, Palmer had become a supporter of American independence,[3] and he was friends with his neighbor John Adams.[1] Palmer served in the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and on the Cambridge Committee of Safety.[3]

Revolutionary War[edit]

Palmer served as an officer of the American patriot militia when the Revolutionary War broke out with the Siege of Boston on April 19, 1775.[1] Issuing the Lexington Alarm, Palmer sent Israel Bissell on his ride to warn and rally colonists that the war with Britain had begun.[3]

Watertown, Wednesday near

10 o'Clock, 19th April 1775.

To all the friends of American liberty be it known that this morning before break of day, a brigade, consisting of about 1,000 to 1,200 men landed at Phip's Farm, at Cambridge, and marched to Lexington, where they found a company of our colony militia in arms, upon whom they fired without any provocation, killed six men and wounded four others. — By an express from Boston, we find another brigade are now upon their march from Boston, supposed to be about 1,000. The Bearer, Israel Bissell, is charged to alarm the country quite to Connecticut, and all persons are desired to furnish him with fresh horses, as they may be needed. — I have spoken with several persons who have seen the dead and wounded; pray let the delegates from this colony to Connecticut see this, they know Col. Foster of Brookfield one of the delegates.— J. Palmer, one of the Committee of S.[7]

On the same day, Palmer fought at the Battle of Lexington[3] and later fought against the British as they retreated from Concord.[6] He first served as captain of the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment and as the war progressed, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and then colonel in the Massachusetts militia.[1][3] His son John fought with him in 1775.[6]

On July 17, 1775, Palmer fought during the Battle of Bunker Hill. He continued to fight during the Siege of Boston until the British withdrew on March 17, 1776.[1] At that time, he was brigadier-general of the militia[1] for Suffolk County, Massachusetts.[3] Palmer was commissioned as brigadier-general of the Continental Army in late 1776, he went on intelligence-gathering missions in Vermont and Rhode Island.[1] George Washington issued letters of commendation to Palmer for his service.[4] In February 1777, he led a successful raid on Newport, Rhode Island that the British held. In October, he led a failed amphibious offensive attack on Newport.[1]

Later years[edit]

After the war, he "suddenly lost his fortune".[4] Heavy debt forced him to leave Germantown, and he started a salt factory on the Boston Neck in 1784,[3] which was a success. But he was not able to pay off all of his debts by the time that he died.[8] Palmer died four years later at his home in Dorchester, Massachusetts, on December 25, 1788.[1][3]

Following his death, Mary moved into Abigail Adams's house, called the Old House (in Quincy, Massachusetts), with her daughters Elizabeth and Polly. In a letter to Abigail Adams, Mary Smith Cranch wrote, "I have been there but a few moments since. They appear to be much gratified with their situation." Mary died in February 1790.[5]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tucker, Spencer C. (14 September 2018). American Revolution: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection [5 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 1143. ISBN 978-1-85109-744-9.

- ^ Kail, Jerry (1976). Who was who During the American Revolution. Bobbs-Merrill. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-672-52216-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Johnson, Allen; Dumas Malone, eds. (1937). Dictionary of American Biography. New York: Scribner's.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Valenti, Patricia Dunlavy (2004). Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, a life. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-8262-2047-9.

- ^ a b "Adams Family Correspondence, volume 8: Mary Smith Cranch to Abigail Adams Braintree July 5th 1789". www.masshist.org. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d Lineage Book of the Charter Members of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Daughters of the American Revolution. 1897. p. 142.

- ^ "The following interesting advices, were this day received here, by two vessels from Newport, and by an express by land [The first news of the battle of Lexington and Concord] [New York, 1775]". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. New York. 23 April 1775. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Family, Adams (1 July 2009). Adams Family Correspondence, Volumes 5 and 6: October 1782 - December 1785. Harvard University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-674-02006-1.