Hohenrechberg Castle

| Hohenrechberg Castle | |

|---|---|

| Rechberg, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany | |

| |

| Coordinates | 48°45′20″N 9°46′55″E / 48.75569°N 9.78201°E |

| Type | Castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Rechberg Stiftung Hans Bader (private foundation) |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruin |

| Site history | |

| Built | First half of the 12th century |

| In use | ca. 1200–1865 |

| Materials | Stone |

| Demolished | 1865 |

| Battles/wars | Thirty Years' War 1648 |

Hohenrechberg Castle (German: Burg Hohenrechberg) is a ruined castle in Schwäbisch Gmünd in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was built as a spur castle on the spur (called "Schlossberg") of the Hohenrechberg mountain, which forms together with the Hohenstaufen Mountain and Stuifen the Three Emperors Mountains, just a few kilometers next to the family seat Hohenstaufen castle of the Staufer dynasty.

Location and importance[edit]

The ruined castle is one of the top tourist destinations in the region Ostwürttemberg, approximately 50 km east of Stuttgart, open to visitors with a little exhibition and equipped with a restaurant and café ("Burgschänke") in the bailey, providing an extraordinary view on the Swabian Forest towards the north and on the Swabian Jura towards the south. On few occasions, depending on weather conditions, it is possible to see as far as the Alps in Switzerland and Austria.

History[edit]

Although the first written proof for "Hohenrechberg" cannot earlier be found than 1274 (the first proof for "Hohenrechberg" in combination with "castle" stems from 1355[1]), experts estimate that the oldest parts of Hohenrechberg castle date back as far as the beginning of the 13th century.[2] Typical for this Staufer dominated period, one can find a lot of humped ashlar masonry surrounding the inner courtyard of the castle.

Hohenrechberg castle was governed by the knights of Hohenrechberg, who served as ministeriales for the Staufer (Hohenstaufen) dynasty. Knights who were named "de Rechberg", however, occur already in the second half of the 12th century. Ulrich of Rechberg was reported to be a castle guard ("castellanus") on Hohenstaufen castle in 1189 and a marshal for the Hohenstaufen family in 1194.[3] For some years he belonged to the ministeriales of Frederick Barbarossa. One of his sons, Hildebrand of Rechberg, equally became marshal. Another son, Siegfried, became the bishop of Augsburg, who died on a crusade 1227.[4]

After the fall of the Staufer family in 1268, the former ministeriales of Rechberg socially managed to climb up into the lower category of noblemen. The Hohenrechberg castle became their own seat and the centre of their attempts to assemble and govern their own territory. This plan could be realized despite the resistance of different opponents, as for example the neighbouring free imperial city of Schwäbisch Gmünd, the Duke of Württemberg, the German kings who wanted to reclaim former Staufer possession, the counts of Helfenstein, south of Hohenrechberg, as well as certain clerical forces. In the upcoming centuries, the different branches of the Rechberg family managed to get hold over a couple of territories, castles and lucrative posts in the South of the German Empire, and by the beginning of the 19th century, they were guaranteed to hold the title "Count" forever.[5]

The castle was constantly enlarged, renovated and adapted to military developments. In the 13th century it received a ring wall with Romanesque window arcades. A second and third defence wall of stones with staircase tower and maschikuli tower, a rare type of defence architecture in Southern Germany,[6] followed throughout the centuries.[7] The lower floor of the gate house was in certain times used as prison. Here, and at many more places a row of late medieval stirrup embrasures can be found. The outer bailey, nowadays partly used as restaurant and café, consisted of a hidden tower storage, a staple, an apartment and of further rooms and fortifications. The former houses inside the inner castle ring wall have been destroyed on 6 January 1865, when a lightning strike hit and burned down the castle.[8] Parts of the buildings have been reconstructed. The Eastern House obtained a new roof and is now used for weddings and parties and contains a little exhibition with castle models and archaeological artefacts.

Hohenrechberg castle remained with a few short intervals in family possession by the Rechbergians until 1986. The intervals consisted of the occupations of the castle from 1554 to 1555,[9] from 1599 to 1601[10] and from 1633 to 1634 by the Duke of Württemberg.[11] In 1648, the castle was attacked, plundered and heavily devastated by French troops.[12] In the end of the 18th century, it had to be opened for Napoleon Bonaparte's Rhine troops: For 1 August 1796 it is reported that General Jean Victor Marie Moreau had a big dinner with eight other generals of his army, more than 40 officers and a couple of other people on the castle.[13] And in World War II American troops got hold of the ruined castle for a couple of months. In 1986 it was sold to Hans Bader,[14] a factory owner from the nearby town Göppingen. After he died in 2006, the Rechberg Stiftung Hans Bader, a private foundation, became the owner.[15]

Tales[edit]

Hohenrecberg Castle is equipped with a long list of tales and sagas. Probably the most popular of which dates back to the 15th century, when the baron of Rechberg of Hohenrechberg was already for a long time absent from his castle, and his wife was praying in the castle chapel that he shall come back home safe and healthy. However, whilst she was praying, she got disturbed by her dog's knocking and scratching at the chapel's door. She felt that something bad was in the air and therefore began to shout: "For God’s sake, shall you be knocking forever!". And indeed, her bad feeling didn't mislead her: The servants brought into the castle her husband's dead body, and ever since when a mysterious knocking is heard within in the ruined castle, the saying goes that a member of the Rechberg family is about to die.[16] A "Ghosthunting Explorer Team" investigated the castle in September 2016, finding "unexplainable" light reflections inside the Gate Tower and "undefinable" knocking sounds next to the inner bridge.[17]

Gallery[edit]

-

Hohenrechberg Castle Ruin from South

-

Hohenrechberg Castle from above (from South)

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Gate House and inner bridge

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Romanesque window arcades from outside

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Romanesque window arcades from inside

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, maschikuli tower seen through inner gate

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, maschikuli tower seen from outer outer ward

-

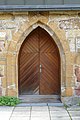

Hohenrechberg Castle, gothic entrance to Eastern Building

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Western Building seen from Eastern Building's roof terrasse

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Romanesque double window

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Romanesque gate through inner ring

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, light slits, southern wall of the inner ring

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, humped rusticated ashlars in Eastern Building's cellar

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Gate House, northside, half-timbered construction

-

View from Gate House on bailey

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, restaurant and café in southern part of the bailey

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, panorama view towards the North from café's terrasse

-

Hohenrechberg Castle Ruin from Southeast

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Outer Bridge

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Outer Bridge and Bailey

-

Hohenrechberg Castle, Inner Bridge, Gate House and Eastern Wall of the Inner Ring

References[edit]

- Notes

- ^ Strobel, Die Burgruine, p 164.

- ^ Strobel, Die Burgruine, p 165.

- ^ Strobel, Die Burgruine, p 165.

- ^ Schmitt, Burgenführer, p 55.

- ^ Setzen, Stammbüchlein, p 4 f.

- ^ Pfefferkorn, Bemerkungen, p 112.

- ^ Strobel, Die Burgruine, p 165.

- ^ Strobel, Die Burgruine, p 165.

- ^ Schmitt, Burgenführer, p 53.

- ^ Schmitt, Burgenführer, p 53 f.

- ^ Setzen, Stammbüchlein, p 51.

- ^ Schmitt, Burgenführer, p 54.

- ^ Schmitt, Burgenführer, p 54.

- ^ Strobel, Die Burgruine, p 164.

- ^ Information about Hans Bader on the Castle’s website (Oct 3, 2022).

- ^ Setzen, Stammbüchlein, p 16 and 205.

- ^ Ghosthunting results documented in a Youtube video.

- Bibliography

- Setzen, Florian H. (2021): Das Stammbüchlein der Grafen und Herren von Rechberg des Vogts der Herrschaft Waldstetten Johann Frey aus Schwäbisch Gmünd von 1643. Geschichtlicher Zusammenhang, Transkription, Originalabdruck (= Quellen aus dem Stadtarchiv Schwäbisch Gmünd – Digitale Editionen vol. 7), Schwäbisch Gmünd: freitagundhäussermann, PDF file, urn:nbn:de:bsz:752-opus4-1369

- Pfefferkorn, Wilfried (2015): Bemerkungen zur Burg Rechberg in Christian Ottersbach, „Türme, Kaponnieren und Bastionen – Flankierungselemente der mittelalterlichen Burgen in Mitteleuropa“, in: Burgen und Schlösser 2/2015, pp 110–112, PDF file

- Strobel, Richard (2005): Die Burgruine Hohenrechberg, Stadt Schwäbisch Gmünd, in: Burgen und Schlösser – Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege n° 3/2005, pp 162–175 ISSN 0007-6201

- Schmitt, Günter (1988): Burgenführer Schwäbische Alb, Band 1 · Nordost-Alb. Wandern und entdecken zwischen Aalen und Aichelberg, Biberach an der Riss: Biberacher Veralgsdruckerei, pp 49–72 ISBN 3-924489-39-4