History of Walla Walla, Washington

The history of Walla Walla, Washington begins with the settling of Oregon Country, Fort Nez Percés, the Whitman Mission and Walla Walla County, Washington.

Native history and early settlement[edit]

Near the mouth of the Walla Walla River, where they had stopped to camp, the Lewis and Clark expedition first encountered the Walawalałáma (Walla Walla people) in 1806 and referred to them as "honest and friendly". In addition to the Walla Walla people, the valley was also inhabited by the Liksiyu (Cayuse), Imatalamłáma (Umatilla), and Niimíipu (Nez Perce) indigenous peoples.[1]

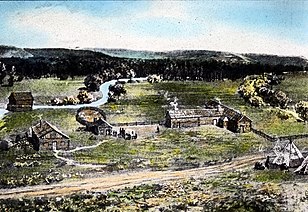

In 1818, the North West Company established Fort Nez Percés to trade with the Walla Walla people land other local Native American groups. At the time, the term "Nez Percé", French for pierced nose, was used more broadly than today, and included the Walla Walla in its scope in English usage.[2] Fort Nez Perce was renamed to Fort Walla Walla when it was acquired in 1821 by Hudson's Bay Company (HBC).[3] It was located west of the present city. The fur trading outpost became a major stopping point for migrants moving west to Oregon Country. It was abandoned in 1855 and is now underwater behind the McNary Dam.[4]

After hearing stories of the "Great Father", William Clark, who was serving as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and the "White Man's Book of Life", four delegates of the Nez Perce[a] people set out on a 2,000 mile expedition to St. Louis, Missouri in 1831. In 1833, a letter from William Walker, a Wyandot leader who served as an interpreter, appeared in the New York Christian Advocate, claiming that the natives spoke of Clark's visit to Oregon country and his accounting of Christianity.[5][7][8][9] Two of the four delegates died in St. Louis and were buried in Calvary Cemetery.[6]

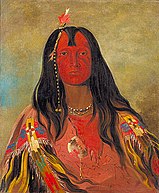

The two remaining delegates, H’co-a-h’co-a-h’cotes-min (No Horns on His Head) and Hee-oh'ks-te-kin (Rabbit's Skin Leggings) encountered George Catlin, a painter who studied native culture, aboard the steamboat Yellowstone in 1832 traveling to Fort Benton in Sioux country. Catlin painted the pair and heard the tale of their journey in search of the veracity of claims that the white man's religion with a savior was better than their own.[9] The paintings now belong to the Smithsonian Institution.[10][11]

In 1835, news of the Nez Perce's search of Clark and Christianity prompted the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to hire Marcus Whitman, a doctor, on a Protestant[12] mission in Oregon country for the Walla Walla tribe.[5][13][14][15] Samuel Parker, a Presbyterian missionary, brokered a deal with the Cayuse, promising to teach them to cultivate crops, like wheat, and yearly trade goods and tools for use of the land.[12] On September 1, 1836, Whitman, and his wife, arrived at Fort Walla Walla.[16] Narcissa Whitman was the first white woman to cross the Continental Divide and settle in the area.[14][17][18]

On October 16, 1836, the Whitmans established the Whitman Mission, in an area inhabited by the Cayuse called Waiilatpu, which means "the place of the rye grass" in the Cayuse language.[13][15] Waiilatpu became an important stop along the Oregon Trail, but no payments were made to the Cayuse, and Umtippe, the chief of the surrounding land, accused Whitman of stealing the Cayuse land and giving preferential treatment to white settlers. The Cayuse people were charged for use of the gristmill, and Whitman sold grains to the settlers, leaving none for the natives.[12][18] The Whitmans stopped trying to convert the natives, shifting their focus to white settler conversion. The mission to convert the natives was unsuccessful, with only two natives ever converting to Calvinism,[12] in part because Catholic ceremonies resonated more with the Cayuse.[4][13] In 1936, the site was designated as a historic site, Whitman National Monument, and January 1, 1963, as a National Historic Site.[19]

On July 24, 1846, Pope Pius IX established the Diocese of Walla Walla and appointed Augustin-Magloire Blanchet to become the first Bishop of Walla Walla.[20][21] In 1847, following a measles epidemic that disproportionately killed indigenous people from a lack of immunity, the Whitmans, along with 12 others, were killed by the Cayuse. In the May 1850 trial regarding the deaths, John McLoughlin, who had worked for HBC and founded Oregon City, Oregon, testified in defense of the Cayuse chiefs that he had warned the Marcus Whitman about the Cayuse custom to kill medicine men whose patients died.[12][22] The Whitman Massacre led to the Cayuse War,[14][23] and Bishop Blanchet fled to St. Paul, Oregon.[20][21] In 1850, the Diocese of Nesqually was established in Vancouver and in 1853 the Diocese of Walla Walla was suppressed and absorbed into the Diocese of Nesqually. Today, the Diocese of Walla Walla is a titular see currently held by Witold Mroziewski, an auxiliary bishop of Brooklyn, New York.[20][21]

After Washington became a United States territory in 1853, and the county had been organized in 1854 by the Washington Territorial Assembly, a treaty council was held at Waiilatpu in May and June 1855, called the Walla Walla Treaty Council. Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens and Joel Palmer, the Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, met with tribal leaders of the Walla Walla, Cayuse, Nez Perce, Yakima, and Umatilla indigenous peoples who cited Tamanwit, or natural law, as an argument against native reservations.[1][24][25][26] The Tawatoy is recorded in the minutes having said, "[T]his land is afraid. I wonder if this ground has anything to say. I wonder if the ground is listening to what is said. I wonder if the ground would come to life ... though I hear what this earth says. The earth says, God has placed me here. The earth says that God tells me to take care of the Indians on this earth."[27]

In 1856, following conflicts between the settlers and the natives, Stevens and Palmer convinced the tribal leaders to agree to surrender 6.4 million acres of land, securing a fraction of their land with a 510,000-acre reservation in northwestern Oregon and $150,000.[1][24][25][26] The amount of land within the boundaries after being surveyed resulted in the natives receiving a reservation only 245,000 acres in size, and was later shrunk again to less than 200,000 acres.[27]

Founding[edit]

Amidst the growing conflicts, in fall 1856, the United States Army established a presence in what would later become the heart of downtown Walla Walla with two separate temporary military forts to deal with the increasing conflicts with the natives.[3][14] The second of the two forts served as quarters for Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe and his soldiers, and a community built up around it called "Steptoeville" while a permanent fort was built adjoining the growing settlement.[3] The namesake was later bestowed on another city, Steptoe, Washington, to honor Steptoe after his loss in the Battle of Pine Creek.[28] The fort was later restored with many of the original buildings preserved, contained in present-day Fort Walla Walla, as well as a museum about the early settlers' lives.[29][4][30]

While the treaty remained unratified, frontiersmen encroached on the promised reservation, adding to the prevailing indigenous distrust of the white pioneers and persisting conflict in the region. The Walla Walla and Umatilla people refused to move to the Umatilla Indian Reservation.[31][32] Immigration into the area was stagnant until 1859, due to an order issued by General John Ellis Wool, who was sympathetic to the natives and refused to become "an exterminator" of indigenous people, to ban settlement east of the Cascade Range due to the ongoing conflicts with the natives.[31][33] Colonel George Wright, who had retaliated against the natives for the murder of the Whitmans and Steptoe's loss,[34] referred to the Cascades as "a most valuable separation of the races". In 1858, the Department of the Pacific was split into two divisions, north and south, with the Department of Oregon covering Washington and Oregon territories commanded by General William S. Harney. General Harney lifted the ban on October 31, 1858, throwing the area open to settlement, after he determined it would be easier to control the natives than to keep the white frontiersmen from moving east.[31][33]

The revocation of the settlement ban triggered thousands of pioneers to swarm to the area. As the home to a burgeoning farming and mining community, Walla Walla grew rapidly.[23] In 1859, Reverend Toussaint Mesplie built and established the city's first church, St. Patrick's Church, and on March 15, Walla Walla county held its first county commission after the first election in the church. The church relocated in 1863, 1865, and 1881, the last building, a Gothic brick building serves as the city's parrish in Historic downtown Walla Walla.[35][36] Also in 1859, Cushing Eells visited the site of the Whitman Mission and sought to establish a monument in memorial of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in the form of a high school, and on December 20, the first educational charter was granted to Whitman Seminary which opened on October 15, 1866. In 1882, the institution's name was changed to Whitman College, the legislature issued a new educational charter as a four-year private college.[37][38]

On April 18, 1859, the United States Senate ratified the 1855 Walla Walla treaty,[29][39][40] and on November 17, 1859, the commission voted to name the settlement Walla Walla.[41][42] Following the ratification, Captain George Henry Abbott was ordered to carry out the forced displacement of the remaining Walla Walla and Umatilla people to the reservation, under the threat of hanging.[43][44]

Incorporation and growth[edit]

Starting in the spring of 1859 and completed in 1862, the first wagon road to cross the Rocky Mountains into the Pacific Northwest, the 611-mile Mullan Road, was constructed by 200 laborers under the direction of Lieutenant John Mullan connecting Fort Walla Walla to Fort Benton in Montana. The road connected the head of the navigation on the Columbia River, where it adjoins the Walla Walla River, with the head of the navigation on the Missouri-Mississippi. Mullan was promoted to Captain after its completion.[45][46] The nearest part of the road followed the modern approximate path from Spokane to Walla Walla via Interstate 90, U.S. Route 195, and U.S. Route 12.[47]

Mullan Road tied Walla Walla to more mining opportunities and became the outfitting point for the Oro Fino, Idaho mines, where gold was discovered on February 20, 1860, by Captain Elias D. Pierce. As more gold was discovered along Mullan road, the population swelled in a gold rush, resulting in an unsuccessful proposal to Congress to split Walla Walla from Washington into its own territory.[48][49] The population exploded over the following decade to 300% its size, making it the largest city in the territory, slating it to be the capital until cities surpassed it again, after it was bypassed by the transcontinental rail lines, in the 1880s.[14][48][49]

On November 29, 1861, the city's first newspapers, and one of the first between Missouri and the Cascades, the Washington Statesman (Statesman), was produced by brothers William Smith and R. B. Smith, who had purchased a used printing press from The Oregon Statesman, and Major Raymond R. Rees and Nemiah Northrop, who had purchased an old press from The Oregonian.[50][51][52][53]

Walla Walla was incorporated on January 11, 1862.[54] The first election was held on April 1, 1862, and Judge Elias Bean Whitman, Marcus Whitman's cousin, was elected as the city's first mayor. Following the election the Statesman alleged the election was improper, and that several ballots were cast by people who did not reside in Walla Walla's boundaries, declaring "there are not to exceed three hundred bona fide voters within the city limits, and yet nearly five hundred votes were polled at the election". Whitman received 416 votes out of 422 total. The election was certified, and during the first year, the number of buildings in the city doubled.[23][48][55][56]

19th century population boom[edit]

The first bank in Washington state, Baker Boyer Bank, was founded on November 10, 1869.[57] In 1858, Dorsey Syng Baker, a doctor and one of the city's first council members,[58] started a mercantile business in Oregon in which he shared a significant portion of his profits with his cash customers. By 1859, he was doing most of his business in Walla Walla with the miners who trusted him to be "fair" and "honest", and moved it to the city in 1861. In 1862, he partnered with brother-in-law John Franklin Boyer, a pioneer banker from San Francisco, and by 1869, so many miners trusted the pair to hold their gold that they founded the bank.[49][59][37][60] The bank was still active as March 2022.[61]

In the 1870s, a group of Seventh-day Adventists (SDA) arrived in Walla Walla and established a congregation in a 60-foot tent. In 1875, Isaac Doren Van Horn, and his wife, Adelia, established the first SDA Church in the Pacific Northwest on land donated by a converted Catholic. The church successfully converted a number of Catholics, soldiers, and other settlers, and the Statesman referred to the church as "the best house of worship in Oregon and Washington Territory, except one, east of the Cascade Mountains".[62] One such soldier, who later became a preacher, was Alonzo T. Jones, who clashed with founder Ellen G. White, eventually leaving Walla Walla and joining John Harvey Kellogg,[62] who invented corn flakes. Both were disfellowshipped by the church.[63] By the 1880s, the Walla Walla Valley had 200 SDA members across five churches, forming the Northwest Adventist organization. In 1892, on a plot of land donated by Nelson Gales Blalock, the city's mayor, Walla Walla College was built and opened, eventually expanding in the basement into the Walla Walla Sanitarium in 1899 by Isaac Dunlap and his wife, Maggie.[64]

By the 1880s, agriculture became the city's primary industry.[14][49] Walla Walla grew to become the agricultural center for wheat, onions, apples, peas, and wine grapes,[65] and was referred to as "the cradle of Pacific Northwest history".[58][55] The technique of dryland farming was developed in the region by John Work, a fur trader who worked for HBC, and Charles Beyer, a British botanist, and carried out by the Whitmans and the Cayuse at Waiilatpu in the 1840s.[66][67][68] Dryland farming became popular in the region, making wheat the backbone of Walla Walla's economy, and the region a breadbasket; with exports as far as England.[23][37] The technique had been used in prehistoric agriculture in the Southwestern United States,[69] in the Prehistoric Mediterranean region,[70][71] and in Prussia, whose Mennonites emigrated to Volgograd, Russia to become Volga Germans,[72] hundreds of which immigrated to Walla Walla after persecution in the Russian Empire in the hopes of capitalizing on their existing wheat farming techniques in the region throughout the end of the 19th-century.[73][74][75][76] The neighborhood of the city where the Volga Germans made their home is known as "Germantown" or "Russische Ecke (Russian Corner)" to locals, referring to the creek that runs through it as "Little Volga".[77] The first German-speaking churches were Lutheran churches.[78][79][80]

In 1886, while Washington was lobbying for statehood, local business man Levi Ankeny donated 160 acres of land to the city to serve as the site of a new prison. Legislators approved the site, and in 1887, the state began transferring prisoners to the Washington Territorial Prison from Saatco Prison, a privately owned facility that was shut down in 1888 because of its poor living conditions.[81][82] The first inmate was a local, William Murphy, who was serving an 18-year sentence for manslaughter.[83] There have been many prison escapes attempted in the prison's history.[14][84][85][86] In 1887, the prison took in its first woman inmate, and had to improvise accommodations until a separate facility was built nearby.[81][87] When Washington became a state in 1889, the facility officially became the Washington State Penitentiary, but inmates nicknamed it "The Hill", "The Joint", "The Walls", and "The Pen".[81]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Some sources say that Flathead (Bitterroot Salish) delegates were sent, but the Nez Perce tribe has claimed all four delegates as belonging to their tribes. It has been suggested that "Flathead" was being used to describe the Nez Perce appearance, rather than the tribe.[5][6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Paulus Jr., Michael J. (February 7, 2008). "Town of Walla Walla is named on November 17, 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Alvin M. Josephy, The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest, Abridged Edition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), p. 51

- ^ a b c "The Many Fort Walla Wallas –- Whitman Mission National Historic Site". National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Colt Denfeld, Duane (July 9, 2011). "Fort Walla Walla". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Haines, Francis (1937). "The Nez Percé Delegation to St. Louis in 1831". Pacific Historical Review. 6 (1): 71–78. doi:10.2307/3634109. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3634109.

- ^ a b Bell, Kim (30 March 2003). "Nez Perce ceremony "reclaims" two Indians". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. pp. C13.

- ^ Prucha, Francis Paul (1986). The great father : the United States government and the American Indians (Abridged ed.). Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-8032-8712-9. OCLC 12021586.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Drury, Clifford M. (1939). "The Nez Perce "Delegation" of 1831". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 40 (3): 283–287. ISSN 0030-4727. JSTOR 20611199.

- ^ a b Lyman, William Denison (2020). Lyman's History of old Walla Walla County. Outlook Verlag. ISBN 978-3752433838.

- ^ "Hee-oh'ks-te-kin, Rabbit's Skin Leggings | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ "H'co-a-h'co-a-h'cotes-min, No Horns on His Head, a Brave | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ a b c d e Harden, Blaine (2021). Murder at the mission : a frontier killing, its legacy of lies, and the taking of the American West. Jeffrey L. Ward. [New York]. ISBN 978-0-525-56166-8. OCLC 1226073551.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Wilma, David (February 14, 2003). "Dr. Marcus Whitman establishes a mission at Waiilatpu on October 16, 1836". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g The new encyclopaedia Britannica. Inc Encyclopaedia Britannica (15 ed.). Chicago, Ill. 2010. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8. OCLC 351325565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "Waiilatpu, Its Rise and Fall, 1836-1847. By Miles Cannon". Washington Historical Quarterly. 7 (3): 251–252. 1916.

- ^ "Territorial Timeline: Whitman Mission established near Walla Walla". Secretary of State of Washington. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ Bommersbach, Jana (2004). "Narcissa Whitman". True West Magazine. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b Belknap, George N. (1961). "Authentic Account of the Murder of Dr. Whitman: The History of a Pamphlet". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 55 (4): 319–346. doi:10.1086/pbsa.55.4.24299944. ISSN 0006-128X. JSTOR 24299944. S2CID 193120962.

- ^ "Park Archives: Whitman Mission National Historic Site". npshistory.com. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ a b c "Titular Episcopal See of Walla Walla". GCatholic. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Paulus Jr., Michael J. (August 17, 2010). "Catholicism in the Walla Walla Valley". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ Tate, Cassandra (April 16, 2010). "Trial of five Cayuse accused of Whitman murder begins on May 21, 1850". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2022-03-04.

- ^ a b c d Paulus Jr., Michael J. (February 26, 2008). "Walla Walla — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Jack (May 20, 2008). "Artist Gustavus Sohon documents the Walla Walla treaty council in May, 1855". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b "Treaty of Walla Walla, 1855 | GOIA". goia.wa.gov. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- ^ a b Trafzer, Cliff (October 22, 2018). "Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855". Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Tate, Cassandra (April 3, 2013). "Cayuse Indians". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2022-02-22.

- ^ Meany, Edmond S. (1923). Origin of Washington geographic names. Seattle: University of Washington press. ISBN 933314241X.

- ^ a b Paulus Jr., Michael J. (February 7, 2008). "Town of Walla Walla is named on November 17, 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Josephy, The Nez Perce, p. 367

- ^ a b c Clark, Robert Carlton (1935). "Military History of Oregon, 1849-59". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 36 (1): 14–59. ISSN 0030-4727. JSTOR 20610911.

- ^ "Umatilla Relationships with US - Making Treaties". trailtribes.org. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b "Visitor information service book for the Deschutes National Forest : an abstract of literature, personal recollections, and interviews dealing with the Deschutes Forest". Oregon State University. 1969. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Lorraine (September 8, 2015). "Stunning '900 Horses' Mural Honors Dark Moment in Native American Horse History". SmartPak. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Paulus Jr., Michael J. (August 17, 2010). "Catholicism in the Walla Walla Valley". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Paulus, Jr., Michael J. (August 18, 2010). "St. Patrick's Church is established in Walla Walla in 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Becker, Paula (March 31, 2006). "Walla Walla County – Thumbnail History". HistoryLink.

- ^ "Washington Territorial Legislature charters Whitman Seminary on December 20, 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla Treaty" (PDF). Secretary of State of Washington. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Gray, Claude M.; Gulick, Bill; Jones, Nard; Maxey, Dr. C. C.; Mcvay, Alfred; Orchard, Vance; Tooker, John (1953). Walla Walla Story - Illustrated Description Of The History And Resources Of The Valley They Liked So Well They Named It Twice. Walla Wall Chamber Of Commerce. ASIN B001SUTYPS.

- ^ Hamilton, Robin (April 29, 2019). "How Walla Walla Got Its Name". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Caldbick, John (June 1, 2013). "Washington Territorial Legislature incorporates City of Walla Walla on January 11, 1862". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Brief History of CTUIR". Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "George H. Abbott". truwe.sohs.org. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "The Mullan Road: A Real Northwest Passage". HistoryLink. November 5, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Swergal, Edwin (December 14, 1952). "Captain Mullan sees it through". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. This Week section. p. 8.

- ^ Clark, Daniel (13 June 2021). "Final work on historic Mullan Road through Walla Walla began 160 years ago". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c Caldbick, John (June 1, 2013). "Washington Territorial Legislature incorporates City of Walla Walla on January 11, 1862". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Reed, Diane (April 29, 2019). "Walla Walla and the Gold Rush". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Wilma, David (February 6, 2003). "Washington Statesman begins publication in Walla Walla on November 29, 1861. - HistoryLink.org". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Blethen, Rob (April 29, 2019). "The First Newspaper in Walla Walla". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Welcome to Walla Walla County". www.co.walla-walla.wa.us. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "The Evening Statesman (Walla Walla, Wash.) 1903-1910". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "City of Walla Walla, Community Information". Ci.walla-walla.wa.us. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Reed, Diane (April 29, 2019). "The Beginnings of Local and Regional Government". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Pickett, Susan (April 12, 1862). "Cousin of Marcus Whitman elected as Walla Walla's first mayor". Union-Bulletin.com. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Becker, Paula (October 17, 2007). "Baker Boyer Bank opens in Walla Walla on November 10, 1869". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Caldbick, John (June 1, 2013). "Washington Territorial Legislature incorporates City of Walla Walla on January 11, 1862". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Baker, W. W. (1923). "The Building of the Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad". The Washington Historical Quarterly. 14 (1): 3–13. ISSN 0361-6223. JSTOR 40474681.

- ^ Bentley, Judy (April 5, 2016). Walking Washington's History: Ten Cities. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295806679.

- ^ White, Martha C. (March 2, 2022). "Oil soars as markets, consumers brace for more volatility". NBC News. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ a b Johnson, Doug R. (1996). Adventism on the Northwestern frontier. Berrien Springs, Mich.: Oronoko Books. ISBN 1-883925-12-6. OCLC 35050746.

- ^ Morgan, Douglas (2001). Adventism and the American republic : the public involvement of a major apocalyptic movement. Martin L. Marty (1st ed.). Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 1-57233-111-9. OCLC 44493139.

- ^ Paulus Jr, Michael J. (May 12, 2009). "The first Seventh-day Adventist church in Walla Walla is organized on May 17, 1874". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Paulus Jr., Michael J. (February 7, 2008). "Town of Walla Walla is named on November 17, 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Rowe, Kara (March 14, 2018). "Agriculture in Washington 1792 to 1900". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Duffin, Andrew P. (2004). "Remaking the Palouse: Farming, Capitalism, and Environmental Change, 1825-1914". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 95 (4): 194–204. ISSN 0030-8803. JSTOR 40491786.

- ^ Meinig, D. W. (1995). The Great Columbia Plain : a historical geography, 1805-1910. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80519-1. OCLC 949883803.

- ^ Araiza, Cassidy (December 10, 2021). "Native Americans' farming practices may help feed a warming world". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Livarda, Alexandra; Orengo, Hector A.; Cañellas-Boltà, Nuria; Riera-Mora, Santiago; Picornell-Gelabert, Llorenç; Tzevelekidi, Vasiliki; Veropoulidou, Rena; Marlasca Martín, Ricard; Krahtopoulou, Athanasia (March 1, 2021). "Mediterranean polyculture revisited: Olive, grape and subsistence strategies at Palaikastro, East Crete, between the Late Neolithic and Late Bronze Age". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 61: 101271. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101271. hdl:10261/228256. ISSN 0278-4165. S2CID 233858862.

- ^ Barker, Graeme (2012). The archaeology of drylands : living at the margin. D. D. Gilbertson. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-64284-2. OCLC 794814572.

- ^ Schillinger, William F.; Papendick, Robert I. (2008). "Then and Now: 125 Years of Dryland Wheat Farming in the Inland Pacific Northwest". Agronomy Journal. 100 (S3). doi:10.2134/agronj2007.0027c. ISSN 0002-1962.

- ^ Long, James W. (1988). From privileged to dispossessed : the Volga Germans, 1860-1917. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-2881-3. OCLC 17385222.

- ^ Schweizer, Cheryl (April 3, 2018). "Volga German settlers subject of museum lecture". Columbia Basin Herald. ISSN 1041-1658. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Schreiber, Steven; Viets, Heather. "Volga Germans in Oregon". Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Becker, Paula (July 16, 2007). "Volga Germans led by Johann Frederich Rosenoff settle near Ritzville in 1883". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Eveland, Annie Charnley (July 19, 2019). "Australia's Walla Walla celebrates 150th anniversary". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Zion German Congregational Church - Walla Walla | Volga German Institute". University of North Florida. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ "Christ Lutheran Church - Walla Walla | Volga German Institute". University of North Florida. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Davenport, Richard (May 1, 2010). "The Integration of the Volga Germans into American Lutheranism". Master of Sacred Theology Thesis.

- ^ a b c Freeman, Bob (February 7, 2021). "A few memorable tales of the history of the Washington State Penitentiary". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Plog, Kari (January 22, 2019). "Hell on Earth: A forgotten prison that predates McNeil Island". KNKX. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Wilma, David (February 6, 2003). "First convicts occupy penitentiary at Walla Walla on May 11, 1887". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Gibson, Elizabeth (April 26, 2009). "Nine die in escape attempt at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla on February 12, 1934". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "10 CONVICTS FLEE PRISON BY TUNNEL; Felons in Washington State Escape Through Thirty-Foot Passage Dug Under Wall". The New York Times. November 4, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Shapiro, Nina (June 12, 2017). "5 of the most daring Washington state inmate escapes". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Stammen, Emma (January 1, 2020). "Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women's Prisons". Scripps Senior Theses.