History of St. Mary's College of Maryland

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

St. Mary's College of Maryland, originally known as St. Mary's Female Seminary, began in 1840 as a secular state-sponsored boarding school for women. Since 1966 it has been a four-year public liberal arts college and in 1992 it became a designated public honors college. One of only two in the nation to hold such a distinction at the time.

The college’s history spans from the early colonial days of St. Mary's City through to the present, including the establishment of religious tolerance and its later loss, long periods of oppression followed by the expansion of freedom as the result of the American Civil War, and through the 19th and 20th centuries to the modern-day public honors college.

On its special research capacity,[2] the school also researches and studies the following historic events and periods as they relate to the local area:[2]

Background[edit]

Colonial setting[edit]

Seventeenth century[edit]

Small painted icon, dating to between circa 1615 and circa 1620, Walters Museum, Baltimore.

St. Mary's College of Maryland is located on the original site of Maryland's first colony, St. Mary's City,[4] which was also the first capital of Maryland[1] and is considered to be the birthplace of religious freedom in America.[5][6]

Colonial St. Mary's City was actually only a town and at its peak had between 500 and 600 residents. However, as the colony quickly expanded and settlements spread throughout the Eastern part of what is now Maryland, the town remained the capitol and representatives would travel from all over the colony to participate in the Maryland General Assembly, the colony's first legislative body.

The Colony was founded under a mandate by the colonial proprietor, Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore of England, that the new settlers engage in religious tolerance of each other.[3][5][7] The first settlers were both Protestant and Catholic during a time of persecution of Catholics.[7] This mandate was unprecedented at the time, as England had been wracked by religious conflict for centuries.

Original Native American village[edit]

St. Mary's College, which has a close partnership with Historic St. Mary's City,[8] was able to put together the following events through a combination or archeological and historic research.[9]

In 1634, at the time of the arrival of the first colonists, there was a Native American village on the site that was a part of the Yaocomico branch of the Piscataway Indian Nation.[10][11] Archeological research shows the presence of native peoples in the area going back more than 10,000 years.[12]

When the colonists first came ashore, the paramount chief of the Yaocomico was already well aware of Europeans due to earlier contact with explorers and traders, as well as news from Virginia tribes that were already co-existing with British colonial settlements. The chief was keen to establish trade with the English and he was also in the process of relocating his people due to war with another tribe. Soon after the new colonists arrived in what is now St. Mary's City, he ordered the Indian village cleared and he sold it to the settlers.[11][13]

The colonists initially lived in Indian longhouses from the prior village, along with some remaining Yaocomico people who had stayed behind to help them. During this period, the Yaocomico taught the colonists how to survive in Maryland's challenging environment.[14] The chief also later put his daughter, the Piscataway Indian princess, Mary Kittamaquund,[15] under the guardianship of a prominent colonist, Margaret Brent,[16] so that Mary could learn English ways and become a bridge and a translator between the two cultures. Her English first name was given to her by the colonists.

1640s: first law requiring religious tolerance[edit]

He also became its first governor and the job of leading the new colony through various trials and tribulations fell on his shoulders.

Painted by Florence MacKubin in 1914.

In the early days of St. Mary's City the young colony suffered from many problems, including periods of violent religious conflict[17] between Protestants and Catholics,[17] in spite of Lord Baltimore's mandate of tolerance,[7][18] as well as disease and the establishment of slavery.[19] Nevertheless, after a period of religious fighting, the residents of St. Mary's City were finally able to establish peace between religious groups for more than 40 years under the Maryland Toleration Act,[1] the first law mandating religious freedom and religious tolerance for people of all Christian faiths, which was conceived, written and ratified by the Maryland Assembly in St. Mary's City.

1641: Possibly first person of African heritage to be elected to a legislative assembly in North America[edit]

Mathias de Sousa was an indentured servant in early St. Mary's City,[20][21] possibly of African and Portuguese heritage,[21] who gained his freedom and established himself as a trader and a mariner in the colony.[21] He was elected to the Maryland Assembly in St. Mary's City, the colony's first legislative body.[21] He traded primarily with the Piscataway Indian nation and also worked as a sailor for the colonial leadership.[21]

1648: first woman petitions for the right to vote in America[edit]

Margaret Brent, a business-savvy and quite successful Catholic settler in St. Mary's City at the time,[17][18] petitioned for the right to vote in the Maryland Assembly[17][18] (also in St. Mary's City, the new colonial capitol).[17][18] This was an unheard of request for a Woman of that era and made Brent very possibly the first woman in America to demand the right to vote.[7][18] However the Maryland colonial Assembly denied her request.[1][7][18]

In the male-dominated frontier environment of the colonies,[7][17] far away from the courts of England, Brent was also forced to defend her legal right to manage her own estate before the Maryland Assembly. She won, making her the first woman in English North America to stand for herself in a court of law and before an assembly. She also would eventually demand the right to vote.[7][17][18]

Brent also served as an attorney before the colonial court,[17][18] mostly representing women of the colony.[18] She is considered to have been very legally astute.[17][18] Surviving records indicate that she pleaded at least 134 cases.[18] Although she did not explicitly campaign for women's rights in general,[7] she is credited for having done so implicitly.[18]

1934 black and white painting by Edwin Tunis.

1690s: renewed persecution of Catholics[edit]

After four decades of peace between Protestants and Catholics, new religious conflict erupted and the Catholic colony leadership was overthrown.[1][22] Catholics lost the right to vote[23] and were prevented from worshipping in public[23][24] (prohibitions that lasted in Maryland for nearly a century, until the late 1700s)[24][25] and the new Protestant leadership moved the capitol to Annapolis.[1][4]

Abandonment of St. Mary's City[edit]

With the capitol moved and widespread persecution of the Catholic community,[23] St. Mary's City was abandoned[4][26] and became a ghost town,[26] except for use as farmland.[4]

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries[edit]

1700–1864: Antebellum plantation period[edit]

St. Mary's College, in partnership with Historic St. Mary's City,[27][9] is engaged in various research projects related to the following events and the historic setting[28][27] in which they occurred:

Entrenchment[edit]

During the 1700s the institution of slavery grew massively in Maryland[19] and became more and more legally entrenched.[19] By the late 1600s there had been about 1,000 slaves in all the different settlements of the Maryland colony combined, but during the first 75 years of the 1700s, the number of enslaved people increased to nearly 100,000, and kept growing.[19]

Over time, the farms in St. Mary's City were consolidated into a large antebellum slave plantation which lasted for more than 150 years until the Civil War.[29] The plantation changed hands a few times, but continued to grow until it reached over 1,715 acres in size.[29] Enslaved African American's became the largest population in St. Mary's City.[29] Records show that slaves on the plantation were bought and sold which would certainly have broken up families.[29] Ruins and archeological research in the area has shown that slaves lived in poorly insulated huts, enduring the extremes of Maryland weather with little comfort or protection. Typically 5 or 6 people lived in 15 foot by 17 foot huts.[30] The plantation system also further caused greater poverty among less privileged free people in the area,[31][32] because the labor market was always depressed due to competition with slave labor.[31][32] Power and wealth therefore proceeded to be concentrated in fewer and fewer hands,[32][33] and the impoverished classes grew in St. Mary's County.[31] Harsh anti-Catholic laws also created barriers for the county's Catholic population.[34] A pattern was established of rural poverty in the county among the non-landed free population.[31]

Maryland penal codes (anti-Catholic laws)[edit]

From 1700 until the 1820s, numerous laws were put in place to "penalize" Catholics for practicing their faith, hence they were called the "penal codes".[24] Catholics were denied the right to vote in Maryland through most of the 1700s.[24][35][36] When anyone in Maryland was sworn into a position of public trust, they were also required to renounce the Catholic church while being sworn in.[35] This was in order to prevent any Catholic person from secretly gaining a position of power. There were also periods where laws denied Catholics the right to purchase or inherit land in Maryland. Catholics were also not allowed to start their own schools.[24] Wealthy Catholics would secretly send their children abroad to get religious education, but to discourage this, Maryland laws were passed fining parents who did this.[37] In order to discourage further importation of Irish indentured servants, who were largely Catholic, a prohibitive tax was imposed to try to prevent bringing any more of them to Maryland.[35] Many Catholics hid their faith and worshiped in secret. Others converted to Protestantism or left the state.

Even after legal restrictions eased in the 1820s, hostility towards Catholics and religious tensions continued in Maryland until the first half of the 20th century.[38]

School founding[edit]

John Pendleton Kennedy[edit]

In 1838, John Pendleton Kennedy, a Maryland author and politician who was a proponent of religious freedom and religious tolerance,[35][39][40] as well as eventually being an opponent of slavery[41][42] (although also criticized in later times for expressing some idyllic stereotypes about Southern plantation life, nevertheless), wrote a book entitled "Rob of the Bowl",[1][43] which was a work of historical fiction that has set in colonial St. Mary's City, Maryland, and was a drama set against the backdrop of the struggle for religious freedom that occurred there.[27][44] The book sparked discussions of the state's history that drew wide attention in Maryland at the time.[44] Kennedy then tapped the increased public interest to campaign for erecting a monument to the memory of religious tolerance in St. Mary's City.

Later on, John Pendleton Kennedy was proposed as a vice-presidential running mate to Abraham Lincoln when Lincoln first sought the Presidency of the United States,[45] although Pendleton was ultimately not selected. Pendleton became a forceful supporter of the Union during the Civil War, and he supported the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation.[46] And then later, since the proclamation did not free Maryland slaves because the state was not in the confederacy,[47] he helped to lead efforts to push for legislation in Maryland that ultimately ended slavery there in 1864.[41][46]

1839: school established as "living monument to religious freedom"[edit]

Students came to the school from all over the state of Maryland.

Religious tensions continued to haunt St. Mary's County and Maryland as a whole in the 1800s, and in response to Kennedy's call for a monument,[44] three prominent residents of St. Mary's County called for the establishment of a new school in St. Mary's City which would instead be a "Living monument to religious freedom".[44]

They quickly won Kennedy's support and together they lobbied the Maryland State legislature. The legislature voted to create, fund and designate a nondenominational[49] school in St. Mary's City as a "Living monument to religious freedom".[49] This was a milestone at the time, because only ten years earlier had the last of Maryland's notorious anti-Catholic "penal codes" been revoked.

Thus the non-denominational "St. Mary's seminary" was born,[1][49] named after the original colonial settlement, now only ruins in the same place where the school was founded.[49] That school would eventually become St. Mary's College of Maryland.[48] The school began as boarding school that included the elementary grades as well as grades 9 through 12.[44] Occasionally boys from the neighboring areas were allowed to take classes as well.[44] A few years later the word "Female" was added to the school's name.[1]

The state sponsored a lottery to raise money for the new school,[48] designating local trustees to administer it,[50] they raised about $18,000[50] and then purchased land in St. Mary's City from Trinity Church[50] for the sole use of the school,[50] and soon commenced construction.[50]

The Monument School[edit]

Due to its designation as a living monument to religious freedom and the founding of the Maryland colony, the school's nickname quickly became The Monument School, and has remained so through to the present. Within a few years the state also required equal representation of all three of the state's major religions on the school's board of trustees.

1861–1865: Civil War[edit]

Historic St. Mary's City, in its close partnership with St. Mary's College,[9][27][51] and affiliated with it any levels,[52] was able to put together the following events and general situation[28][53] at the nearby plantation[28][54][51] through a combination of archeological and historic research:[51]

Union troops in St. Mary's City[edit]

The school was not a part of the plantation in St. Mary's City, but these events occurred next door to the school,[28] sometimes within sight of classroom or dorm windows. Students and faculty of the time were witnesses to some of the local history of this era, literally watching the historic struggle and eventually, the resulting expansion of human rights, visible out the windows of the school.

Steamboat era[edit]

From the founding of the school until 1933, students traveled to the school each year by steamboat,[48] coming down the Chesapeake Bay from Annapolis and Baltimore.[58] This usually meant an overnight trip.[48]

The roads of St. Mary's County were largely unpaved and notoriously treacherous until the 1930s, and so water transportation was the best way to access the county. The school also received its mail and supplies by boat. Steamboats would pull up to the school dock, just below the old Statehouse grounds, as often as twice a week. For a fee they would also carry students and faculty on outings over to Piney Point, or to Virginia.

By the 1930s, the steamboat service to the school was more of a tradition than a necessity, and it was losing clientele Bay-wide due to the increased usage of automobiles.[56] The main roads leading to the college were also by then paved. So when a storm destroyed the school dock in 1934,[56] the school let go of the steamboat service and transportation to the college was thereafter only by automobile.[56]

-

Annie Elizabeth Thomas Lilburn, known as "Miss Lizzie" by students, was a principal of the school (1881-1895).[48]

-

Student's report card from St. Mary's Female Seminary, circa 1870.

-

St. Mary's Female Seminary, circa 1890.[59] The building was erected for the school by the state of Maryland. Students from all over the state attended the school, many on scholarship or grants.

-

Students at St. Mary's Female Seminary in the late 1800s

-

Photo of faculty at St. Mary's Female Seminary, 1898

Dance at St. Mary's[edit]

Dance productions and later on, social dances, have been a mainstay of the school's culture and life for over a hundred years.[60] Productions often included elaborate costumes and were prepared for with intensive training.[60] Later on, social dances became the center of social life for the school, often attended by uniformed cadets from Charlotte Hall Military Academy, and starting in the 1940s, young soldiers and sailors from the county's three new military bases.[60]

St. Mary's College of Maryland archive: "History of Dance at St. Mary's"[60]

In January 2014, the St. Mary's College Archives published an article called the "History of Dance" at St. Mary's".[60] It chronicles 100 years of dance at St. Mary's Seminary and College.[60] The article notes that dance has been central to the school's culture since at least the late 1800s.[60]

Twentieth century[edit]

1926–1966: junior college period[edit]

She was Principal of St. Mary's Female Seminary and later its first College President, after its expansion.[61]

Women gaining right to vote results in call to convert seminary to a junior college[edit]

Mary Adele France, the principal of St. Mary's Female Seminary at the time,[61] felt inspired by the fact that women had just recently gained the right to vote in America.[44] This led her to believe that women deserved more access to a college education as well.[44] She petitioned the Maryland State Legislature to convert the school to a two-year junior college. This was necessary, France wrote, in order to ready young women for "an economic place in the world".[44]

The time is past when we educated our daughters for ornaments only[62]

M. Adele France, first President,[61]

St. Mary's Female Seminary Junior College, 1926[61][62]

France then embarked on a determined and ultimately successful lobbying campaign in Annapolis. In 1926, by order of the Maryland Legislature, St. Marys College was expanded to a two-year Female Junior College, combined with the last two years of high school (four years total).[62] At that time, the college dropped the 9th and 10th grades, but combined grades 11 and 12 with the first two years of college, making it a four-year institution, although only a "Junior College" at the upper two levels.[63]

The school's new name became the "St. Mary's Female Seminary Junior College".[61]

In 1949 the school became coeducational and the word "Female" was dropped from the school name.[1][64]

1964: First Black student admitted to the college[edit]

Four-year, liberal arts college (1966–present)[edit]

1966: Campaign to end rural poverty results in expansion, renaming school "St. Mary's College of Maryland"[edit]

Goodpaster was also a decorated veteran of World War II, where he commanded the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion in North Africa and Italy until he was severely wounded. For his service he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star, and two Purple Hearts. He continued in the Army as a desk officer and eventually rose to the highest levels of the United States Military Command.

In retirement he also became a vocal advocate for the elimination of nuclear weapons and the establishment of a permanently nuclear-free world.

A building on the campus of St. Mary's College of Maryland, Goodpaster Hall, is named after him.

J. Frank Raley, a St. Mary's County politician and advocate for education,[65] had a dream of eliminating the then-deeply entrenched rural poverty in St. Mary's County by greatly enhancing education in the region. He led a campaign to significantly expand all levels of education, by securing numerous capitol programs from the Maryland state Legislature.[66] This also included a campaign by Raley to expand St. Mary's Seminary Junior College into a four-year liberal arts institution.

Raley was also noted for supporting integration of St. Mary's County schools[67] and elimination of racial segregation.[67]

Raley then followed this with years of ongoing, relentless, education-related advocacy on behalf of the county.[67]

After extensive lobbying by Raley and others, the Maryland State legislature ordered St. Mary's Junior College expanded to a four-year liberal arts college in 1966[67] (also dropping the high school grades) and renaming it St. Mary's College of Maryland.

|

By the 1967–68 academic year, the first four-year students began college studies.[68] Building projects to expand the campus and to build a new library began in earnest. The first Bachelor of Arts (BA) degrees were awarded.

School gains prominence in archeology and historical research[edit]

1968: Establishment of St. Mary's City Commission (later named "Historic Mary's City")[edit]

The St. Mary's City Commission was charged with archeological and historical research of St. Mary's City and its rich colonial past, as well as its critical roles in the development of democracy in Maryland and North America as a whole. The commission was also charged with developing historic interpretation programs for the general public.

Although a separate institution from he school, over time, St. Mary's College and Historic st. Mary's City became highly interdependent institutions.[9][27] For 40 years, St. Mary's College of Maryland and Historic St. Mary's City have jointly operated[27] the internationally recognized Historic Archeology Field School,[69] which is considered one of the top archeology field schools in the nation.[27]

In addition, the two institutions jointly offer year-round classes in hands-on classes in archeology, museum studies, African-American studies, history, and democracy studies.

Denzel Washington Jr. in St. Mary's City[edit]

This affected the course of his career, leading him to take numerous other roles involving historic figures.

Denzel Washington Jr. played the earliest role of his professional acting career in St. Mary's City, Maryland when he was 21 years old (he did a two-minute appearance in a prior production, but his role in St. Mary's City was very substantial).[70] During the entire summer season of 1976, he performed in the stage production of "Wings of the Morning"[70][71] a historical play about the founding of the Maryland colony and the beginnings of democracy there. Washington played the role of a real historical figure from colonial St. Mary's City, Mathias de Sousa,[20][70][71] who was possibly of both African and Portuguese heritage[20] and if so, was America's first Black legislator.[20] This was also Denzel Washington's first role playing a real historical character (although the play itself was fictionalized in order to fill gaps in historical information).[71] The experience led Washington to take on numerous other acting roles involving historic figures.

Influence on Washington's acting career[edit]

This experience had a lasting influence on the course of Washington's acting career, as he later sought out numerous historical roles, including portrayals of Steve Biko, Malcolm X, Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, Herman Boone and Melvin B. Tolson.

Washington also later won an Academy Award for his role in the film Glory where he played the part of Private Silas Trip, who served in a United States Colored Troops regiment during the American Civil War.

Historic St. Mary's City starts living history program, involving student actors[edit]

This may have had a lasting influence on Historic St. Mary's as well, although after some debate, the commission at the time discouraged the state for some years afterwards from allowing fictionalized historical theater productions in the historic area. The commission later secured funding for a living history program, including use of period actors in order to interpret area history to the public.

The living history program has continued in Historic St. Mary's City for over 30 years, involving students from St. Mary's College of Maryland in acting roles that interpret area history.

1980s: national recognition for school as a "prominent Liberal arts college"[edit]

In the 1980s US and News and World Report magazine began to recognize St. Mary's College as a prominent and unique liberal arts college in the public sector[72] that was seeking to emulate far more expensive Ivy League colleges[72] while providing such education at far lower public college prices.[72]

Lucile Clifton[edit]

In 1989, former Poet Laureate of Maryland, Lucille Clifton, who was twice nominated for the Pulitzer prize, and also winner of an Emmy Award, joined the faculty at St. Mary's College of Maryland in 1990,[73] thereby becoming one of the school's most prominent faculty members in its history.[73] She remained on the faculty for more than fifteen years.[73] An installation of plaques with Clifton's poetry are on or near the path around St. John's Pond on the campus,[73] and comprise an outdoor "poetry walk"[73] with a view of the pond[73] and also the St. Mary's River, which Clifton was known to love.

1992: "Public Honors College" designation[edit]

Ted Lewis[edit]

Due to the efforts of then St. Mary's College President Ted Lewis, the school was designated by the state of Maryland as a Public Honors College in 1992,[74][75][76] making it one of only two such colleges in the nation at the time.[77]

Lewis was drawn to the school by its goal of developing a public liberal arts college into an institution that could compete academically with elite private colleges. He served as president from 1982 to 1996 and oversaw the largest advancement of the school's standing in its history. The school went on to win numerous top national rankings and became nationally recognized.

Lewis himself had grown up in a blue-collar family in Warwick Rhode Island, his father only had an eighth-grade education and so Lewis was in the first generation of his family to attend college. Initially he wasn't able to stay engaged with his studies and he dropped out, but later, after a period of military service, he returned to pursuing an education, following through all the way to obtaining a Doctorate degree and then becoming an educator and later a college administrator. He was also a noted and very prolific poet in his younger days.

During his time as president, Lewis oversaw an expansion of the Brent scholars' program for first generation college students. He also oversaw a more than doubling of the school's African American student population from 6% in 1982, to 14% in 1992.[78] During this era, the State Legislature also charged the school with a mission to remain affordable to public education sector students,[76] while offering a Liberal Arts education normally only available at private liberal arts colleges.[76]

Growing pains[edit]

The college struggled to meet this cost containment goal, as it had also been required by the state to grow considerably at the same time, across numerous dimensions, in order to fulfill its new role as the state's public honors college.[78] This era also saw steady increases in tuition.[78]

Twenty-first century[edit]

2002: Establishment of the Center for the Study of Democracy at St. Mary's College[edit]

Bradlee also served on the Board of Trustees for St. Mary's College of Maryland for many years.[79]

Because the historic site of the college has been at the center of so many "firsts" in the struggle for democracy in Maryland and North America, the Center for the Study of Democracy was established by St. Mary's College in 2002 to enhance and foster interdisciplinary studies[81][27] of the history of the struggle for the establishment and expansion of democracy in all its forms.[2][81]

The center also studies the application of lessons gleaned from this history to modern day struggles and events.[2]

- The center draws on study of the following historic struggles for democracy that occurred in St. Mary's City

- 1600-1870s: The struggle for religious tolerance (the effort to establish civil law and practices that establish and protect the right of people to practice the faith of their conscience without interference).[2]

- 1648:The struggle for Women's suffrage (women's right to vote) and equality of opportunity in business, 1642-1649[2]

- 1863-65:The struggle for "minority rights"[2] (including freedom from oppression and soon after, the right to vote, first guaranteed to people of all races in Maryland in 1870).[2] 1865-1950s, the struggle for Civil Rights.

- 1670s: The struggle for freedom of the press (its establishment and attempts to eliminate or curtail it)[2]

- Issues related to the emergence of new democracy in historic Maryland and the United States[2][81]

- Learning from history: application of historical research to modern day issues

The center's mission is to apply lessons[81] and inspiration[2] derived from the area's history[2] to study of the following modern day issues[2][81]--

- Preservation and furtherance of democracy in the United States and other developed nations[2][81]

- Inclusion of minorities and women in the democratic process around the world[2]

- Special focus on issues related to emerging democracies in countries that have never experienced it before.[2]

-

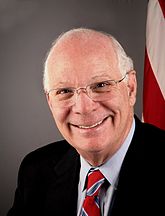

Ben Cardin, Senator from Maryland and former Speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates, active advisory board member of the Center For the Study of Democracy.

-

Former Maryland Governor William Donald Schaefer was an active advisory board member of the Center For the Study of Democracy for many years.

-

Former U.S. District Court judge Thomas Penfield Jackson, was involved in the founding of the Center for the Study of Democracy, was also active as an advisory board member for many years.

-

Anthony Lake, former U.S. National Security Adviser, was active on the advisory board member of the Center For the Study of Democracy for many years.

2009-2010: school ranked second in the nation for student Fulbrights among public colleges[edit]

St. Mary's College has had many students and faculty win Fulbright awards.[82][83] In the 2009–2010 academic year, the college had the second highest number of student Fulbright winners of any public liberal arts college in the nation.[83]

2011-2012: school ranked third in the nation for faculty Fulbrights among public and private colleges[edit]

In the 2011–2012 academic year, St. Mary's College of Maryland had the 3rd highest number of faculty Fulbright winners in the United States among nation among public and private baccalaureate colleges (undergraduate colleges).[82]

2013: African-American student enrollment hits record low[edit]

In 2013, African-American student enrollment hit a record low of 7%. A major reason cited is growing tuition and a feeling that the state is not funding the schools adequately. Ivy league schools are also competing heavily for top minority students. First generation college students of all races come from families still recovering from the recession.

By spring 2014, the number had rebounded slightly to 8%. The college has been undergoing a multi-front effort to greatly increase African-American student enrollment.

2014: School's first African-American President appointed[edit]

Two other top African American administrators were also appointed.

See also[edit]

- Colonial Maryland

- Maryland in the American Civil War

- History of Maryland

- St. Mary's City, Maryland

- Women's suffrage

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "St. Mary's County, Maryland: Historical Chronology", Maryland Manual Online, Maryland State Archives, Government of the State of Maryland

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Center for the Study of Democracy: Purpose and Inspiration for Our Work", St. Mary's College of Maryland, CFSOD, "St. Mary's College of Maryland". Archived from the original on 2014-09-22. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- ^ a b Cecilius Calvert, "Instructions to the Colonists by Lord Baltimore, (1633)" in Clayton Coleman Hall, ed., Narratives of Early Maryland, 1633-1684 (NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 11-23.

- ^ a b c d Kenneth K. Lam, "Unearthing early American life in St. Mary's City: St. Mary's City is an archaeological jewel on Maryland's Western Shore", Baltimore Sun, August 30, 2013, http://darkroom.baltimoresun.com/2013/08/unearthing-early-american-life-in-st-marys-city/#1

- ^ a b "Reconstructing the Brick Chapel of 1667" Page 1, See section entitled "The Birthplace of Religious Freedom" [1] Archived March 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greenwell, Megan (2008-08-21). "Religious Freedom Byway Would Recognize Maryland's Historic Role". ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dr. Lois Green Carr, "Margaret Brent (ca. 1601-1671)", MSA SC 3520-2177, Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002100/002177/html/bio.html

- ^ "Anthropology Department: Historic St. Mary's City", St. Mary's College of Maryland describes close and multi-leveled relationship between Historic St. Mary's City and St. Mary's College of Maryland

- ^ a b c d "Anthropology Department: Historic St. Mary's City", St. Mary's College of Maryland describes close and multi-leveled relationship between Historic St. Mary's City and St. Mary's College of Maryland "Anthropology Department: St Mary's College of Maryland". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "The Founding of St. Mary's City: The Colonists and the Yaocomaco", Historic St. Mary's City, http://hsmcwitchottproject.blogspot.com/2011_06_01_archive.html

- ^ a b "Founding of Maryland - Educational Project for Elementary and Middle School Students", Maryland State Archives Website, Maryland Public Television and Maryland State Archives (January–February 2003), Archives of Maryland, (Biographical Series) Leonard Calvert (ca. 1606-1647), MSA SC 3520-198, written by Maria A. Day, MSA Archival Intern http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/000100/000198/html/lcalvbio.html

- ^ The colonists initially lived in Indian longhouses called "Witchotts""The Founding of St. Mary's City: The Colonists and the Yaocomaco", Historic St. Mary's City, http://hsmcwitchottproject.blogspot.com/2011_06_01_archive.html

- ^ "The Founding of St. Mary's City: The Colonists and the Yaocomaco", Historic St. Mary's City, http://hsmcwitchottproject.blogspot.com/2011_06_01_archive.html

- ^ "The Founding of St. Mary's City: The Colonists and the Yaocomaco", Historic St. Mary's City, http://hsmcwitchottproject.blogspot.com/2011_06_01_archive.html

- ^ "Margaret Brent (ca. 1601–1671)" Monica C. Witkowski, Encyclopedia Virginiana, See section entitled "Migration to Maryland", second paragraph http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Brent_Margaret_ca_1601-1671

- ^ "Margaret Brent (ca. 1601–1671)" Monica C. Witkowski, Encyclopedia Virginiana, See section entitled "Migration to Maryland", second paragraph http://encyclopediavirginia.org/Brent_Margaret_ca_1601-1671

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Notable Maryland Women: Margaret Brent, Lawyer, Landholder, Entrepreneur", Winifred G. Helms, PhD, Editor, Margaret W. Mason, section author, Tidewater Publishers, Cambridge Maryland, 1977, page 5, republished online by the Maryland State Archives: Online manual, http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002100/002177/pdf/notable.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jo-Ann Pilardi, Baltimore Sun, "Margaret Brent: a Md. founding mother", March 05, 1998 http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1998-03-05/news/1998064114_1_margaret-brent-lord-baltimore-calvert

- ^ a b c d The Maryland State Archives and the University of Maryland at College Park, "A Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland" section entitled "II The Plantation Revolution", page 7, 2007, http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/intromsa/pdf/slavery_pamphlet.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g Maryland State Archives, Teaching Maryland History, "Mathias de Sousa" http://teaching.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000000/000003/html/t3.html

- ^ a b c d e "Matthias da Sousa: Colonial Maryland's Black, Jewish Assemblyman", Susan Rosenfeld Falb, MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE, VOL. 73, No. 4, DECEMBER 1978 http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5800/sc5881/000001/000000/000293/pdf/msa_sc_5881_1_293.pdf

- ^ "Vanished Colonial Town Yields Baroque Surprise (Published 1989)". 1989-02-05. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ a b c "The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People, Volume I: To 1877", By Paul Boyer, Clifford Clark, Karen Halttunen, Sandra Hawley, Joseph Kett, "Chapter: 4 The Bonds of Empire: 1660-1740" page 70, Cengage Learning, publisher, January 1, 2012

- ^ a b c d e Francis Graham Lee, "All Imaginable Liberty: The Religious Liberty Clauses of the First Amendment", page 22, University Press of America (June 6, 1995)

- ^ "America as a Religious Refuge: The Seventeenth Century, Part 2 - Religion and the Founding of the American Republic | Exhibitions (Library of Congress)". www.loc.gov. 1998-06-04. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ a b Frank D. Roylance, Evening Sun, "They're unearthing more than a chapel at St. Mary's site BURIED PAST", November 13, 1990 http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1990-11-13/news/1990317111_1_chapel-mary-city-brick

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Archaeology, Narrative, and the Politics of the Past: The View from Southern Maryland", Page 41, Julia King, University of Tennessee Press; July 30, 2012, ISBN 1572338512, ISBN 978-1572338517

- ^ a b c d "Slave Dwelling Project: Talk and Tour", St. Mary's College of Maryland, schedule of events, http://www.smcm.edu/calendar/events/index.php?com=detail&eID=3118 Archived 2014-08-26 at archive.today

- ^ a b c d "All of Us Would Walk Together: From City to Plantation", Historic St. Mary's City https://hsmcdigshistory.org/walktogether/index.php/project/labor-in-marylan/

- ^ Historic St. Mary's City, "We would walk together: Life in the Quarters", https://hsmcdigshistory.org/walktogether/index.php/project/life-in-the-quarters/

- ^ a b c d "Southern Maryland Economy" (1800s economic history), Southern Maryland Heritage Area Consortium (SMHAC), http://www.destinationsouthernmaryland.com/c/376/1812southernmarylandeconomy Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine See also "About Page" http://www.destinationsouthernmaryland.com/c/253/faq Archived 2014-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Did slavery make economic sense?". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ "Southern Maryland Economy" (1800s economic history), Southern Maryland Heritage Area Consortium (MHAC), http://www.destinationsouthernmaryland.com/c/376/1812southernmarylandeconomy Archived 2014-03-06 at the Wayback Machine See also "About Page" http://www.destinationsouthernmaryland.com/c/253/faq Archived 2014-09-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Casino, Joseph J. "Roman Catholics in the colonial period." in the fourth paragraph in the article, In Smith, Billy G., and Gary B. Nash, eds. Encyclopedia of American History: Colonization and Settlement, 1608 to 1760, Revised Edition (Volume II). New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2010. American History Online. Facts On File, Inc. http://www.fofweb.com/activelink2.asp?ItemID=WE52&iPin=EAHII354&SingleRecord=True (accessed February 26, 2014).

- ^ a b c d Robert J. Brugger, "Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980", Johns Hopkins University Press (August 28, 1996) ISBN 0801854652 ISBN 978-0801854651

- ^ "The Enduring Vision: A History of the American People, Volume I: To 1877", By Paul Boyer, Clifford Clark, Karen Halttunen, Sandra Hawley, Joseph Kett, "Chapter: 4 The Bonds of Empire: 1660-1740" page 70, Cengage Learning, publisher, Jan 1, 2012,

- ^ Francis Graham Lee, "All Imaginable Liberty: The Religious Liberty Clauses of the First Amendment", page 359, University Press of America (June 6, 1995)

- ^ Robert J. Brugger, "Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980", Johns Hopkins University Press (August 28, 1996), Page 493, ISBN 0801854652 ISBN 978-0801854651

- ^ "Discourse on the life and character of George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore", John Pendleton Kennedy, page 43, University of Michigan Library (January 1, 1845), ASIN: B003B65WS0

- ^ Kennedy, John Pendleton (1845). Discourse on the Life and Character of George Calvert, the First Lord Baltimore. J. Murphy.

- ^ a b "Immediate emancipation in Maryland. Proceedings of the Union State Central Committee, at a meeting held in Temperance Temple, Baltimore, Wednesday, December 16, 1863", 24 pages, Publisher: Cornell University Library (January 1, 1863), ISBN 1429753242, ISBN 978-1429753241

- ^ "The Life of John Pendleton Kennedy", Henry T. Tuckerman Kuchapishwa na Kessinger Publishing, Llc, ISBN 978-1-164-43961-5, ISBN 1-164-43961-8

- ^ "Rob of the Bowls" John Pendleton Kennedy, 1838, G.P. Putnam and Sons, New York, http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/kennedy/kennedy.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "St. Marys: A When-Did Timeline", page 6, By Janet Butler Haugaard, Executive Editor and Writer, St. Mary's College of Maryland with Susan G. Wilkinson, Director of Marketing and Communications, Historic St. Mary's City Commission and Julia A. King, Associate Professor of Anthropology, St. Mary's College of Maryland St. Marys College Archives "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ The Magazine of American History, Vol. 29, 1893, 282–283

- ^ a b Barbara Jeanne Fields, "Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (Yale Historical Publications Series)", Publisher: Univ Tennessee Press; (July 30, 2012), ISBN 1572338512, ISBN 978-1572338517

- ^ "The not-quite-Free State: Maryland dragged its feet on emancipation during Civil War". Washington Post. 2023-05-18. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ^ a b c d e f J. Frederick Fausz, Monument School of the People: A sesquicentennial history of St. Mary's College of Maryland, 1840-1990, Page 24, SMCM, ISBN 0962586706, ISBN 978-0962586705 Note: Citation is on right page (25) at bottom, while photo is on page 24.

- ^ a b c d "Archaeology, Narrative, and the Politics of the Past: The View from Southern Maryland", Page 68, Julia King, University of Tennessee Press; July 30, 2012, ISBN 1572338512, ISBN 978-1572338517

- ^ a b c d e J. Frederick Fausz, "Monument School of the People: A sesquicentennial history of St. Mary's College of Maryland", 1840-1990", Page 32, SMCM, ISBN 0962586706, ISBN 978-0962586705 https://archive.org/stream/monumentschoolof00faus#page/32/mode/2up/search/lottery

- ^ a b c "Echoes from Past Generations" Anne Dowling Grulich for the Maryland Heritage Project, http://www.smcm.edu/rivergazette/archives/decjan09/echoes.html Archived 2014-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Anthropology Department: Historic St. Mary's City, St. Mary's College of Maryland, describes close and multi-leveled relationship between Historic St. Mary's City and St. Mary's College of Maryland"Anthropology Department: St Mary's College of Maryland". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ "An Interview With Terry Brock", October 20, 2013, Delia Titzell, Co-News Editor, http://thepointnews.com/2013/10/an-interview-with-terry-brock-2

- ^ "Challenges of Working on the Brome Howard Inn's Exhibit: All of Us Would Walk Together", Steven Gentry, http://stmaryscity.org/walktogether/index.php/challenges-of-working-on-the-brome-howard-inns-exhibit/

- ^ "History of the College", St. Mary's College of Maryland, caption of source photo reads: "Students arriving on campus in 1900, (St. Mary's Archives)" http://www.smcm.edu/about/ourhistory.html Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Fausz, J. Frederick (1990). Monument school of the people : a sesquicentennial history of St. Mary's College of Maryland, 1840-1990. St. Mary's College of Maryland Library. St. Mary's City, Md. : St. Mary's College of Maryland. ISBN 978-0-9625867-0-5.

- ^ Fausz, J. Frederick (1990). Monument school of the people : a sesquicentennial history of St. Mary's College of Maryland, 1840-1990. St. Mary's College of Maryland Library. St. Mary's City, Md. : St. Mary's College of Maryland. ISBN 978-0-9625867-0-5.

- ^ a b By Janet Butler Haugaard, Susan G. Wilkinson, Julia A. King, "St. Mary's, A When-Did? Timeline", page 16, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "History of the College", St. Mary's College of Maryland, caption of source photo reads: "St. Mary's Female Seminary-1890, (St. Mary's Archives)" http://www.smcm.edu/about/ourhistory.html Archived 2014-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The History and Culture of Dances at St. Mary's College of Maryland", St. Mary's College of Maryland Archives, Emily Hiner, January, 2014, http://www.smcm.edu/archives/exhibits/dance_at_st_marys.html Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f "The Revolutionary College Project: Notable Alumni: Mary Adele France (Feb. 17, 1880 – Sept, 1954)", Washington College, http://www.washcoll.edu/centers/starr/revcollege/alumni/alumnibios.html

- ^ a b c "St. Marys: A When-Did Timeline", page 11, By Janet Butler Haugaard, Executive Editor and Writer, St. Mary's College of Maryland with Susan G. Wilkinson, Director of Marketing and Communications, Historic St. Mary's City Commission and Julia A. King, Associate Professor of Anthropology, St. Mary's College of Maryland St. Marys College Archives "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "St. Marys: A When-Did Timeline", page 12, By Janet Butler Haugaard, Executive Editor and Writer, St. Mary's College of Maryland with Susan G. Wilkinson, Director of Marketing and Communications, Historic St. Mary's City Commission and Julia A. King, Associate Professor of Anthropology, St. Mary's College of Maryland St. Marys College Archives "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "St. Mary's College of Maryland: Historical Evolution", Maryland Manual Online, Maryland State Archives, Government of the State of Maryland, http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/25univ/stmarys/html/stmarysh.html

- ^ "J. Frank Raley, Jr.: On Higher Education", The Slackwater Center, St. Mary's College of Maryland, http://www.smcm.edu/slackwater/onlineexhibits/JFrankRaley/Index.html Archived 2014-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "J. Frank Raley, Jr.: On Higher Education", The Slackwater Center, St. Mary's College of Maryland, http://www.smcm.edu/slackwater/onlineexhibits/JFrankRaley/jfreducation.html Archived 2014-08-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d "St. Mary's College Mourns the Passing of J. Frank Raley", Wednesday, August 22, 2012, http://lexleader.net/st-marys-college-mourns-passing-frank-raley/

- ^ Mike Bowler, Baltimore Sun, "St. Mary's excellence began with Jackson: Former president writes a memoir about turning the small school into a top-notch public liberal arts college.", The Education Beat, November 06, 2002, http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2002-11-06/news/0211060051_1_jackson-mary-college-college-of-maryland

- ^ "Anthropology Department: Historic St. Mary's City", St. Mary's College of Maryland describes close and multi-leveled relationship between Historic St. Mary's City and St. Mary's College of Maryland, "Anthropology Department: St Mary's College of Maryland". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ^ a b c d e f "St. Mary's: A 'When-did?' Timeline", Haugaard, Susan G. Wilkinson; Wilkinson, Susan G.; King, Julia; page 30, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d "Matthias da Sousa: Colonial Maryland's Black, Jewish Assemblyman", Susan Rosenfeld Falb, MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE, VOL. 73, No. 4, DECEMBER 1978, page 97, http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5800/sc5881/000001/000000/000293/pdf/msa_sc_5881_1_293.pdf

- ^ a b c Fausz, J. Frederick (1990). Monument school of the people : a sesquicentennial history of St. Mary's College of Maryland, 1840-1990. St. Mary's College of Maryland Library. St. Mary's City, Md. : St. Mary's College of Maryland. ISBN 978-0-9625867-0-5.

- ^ a b c d e f "Lucille Clifton Winner of Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize", 5/11/2007, Baynet.com, http://www.thebaynet.com/News/index.cfm/fa/viewStory/story_ID/5758/comment_categoryID/5758:News/comment/Y

- ^ Maryland State Archives, Online Manual, "St. Mary's College of Maryland: Origin & Functions" http://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/25univ/stmarys/html/stmarysf.html

- ^ CBS Baltimore, Local, "St. Mary's College Of Maryland Names New President", March 19, 2014, http://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2014/03/19/st-marys-college-of-maryland-names-new-president/

- ^ a b c "When the Answer to 'Access or Excellence?' Has to Be 'Both': St. Mary's of Maryland, a public honors college, wants to be affordable while offering a private liberal arts-style experience" Beckie Supiano, Chronicle of Higher Education, October 16, 2011, https://chronicle.com/article/When-the-Answer-to-Access-or/129423/?sid=wb

- ^ "Edward T. Lewis Ph.D, Director, The Wills Group"[dead link], Executive Profile, Bloomberg Business Week

- ^ a b c "Trading Dollars for Independence" See section entitled "Autonomy Woes", Business Officer magazine, National Association of University and College Business Officers, Laurie Stickelmaier, http://www.nacubo.org/Business_Officer_Magazine/Magazine_Archives/April_2004/Trading_Dollars_for_Independence.html Archived 2014-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e "Investigating Power: Ben Bradlee -- Career Timeline", Investigatingpower.org, http://www.investigatingpower.org/journalist/ben-bradlee/

- ^ a b "Center for the Study of Democracy: Purpose and Inspiration for Our Work", St. Mary's College of Maryland, CFSOD, "St. Mary's College of Maryland". Archived from the original on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ^ a b c d e f "Pax Defense Forum to Focus on China Seas" Lexington Leader, Thursday, April 11, 2013 · http://lexleader.net/pax-defense-forum-focus-china-seas/

- ^ a b "Top Producers of U.S. Fulbright Scholars by Type of Institution". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2012.

- ^ a b "SMCM Awarded Highest Number of Fulbright Scholars in Maryland: Second Highest in Country for Public Colleges". Southern Maryland Online. October 23, 2009. Retrieved March 31, 2014.