Heiji Monogatari Emaki

| Heiji Monogatari Emaki | |

|---|---|

| ja: 平治物語絵巻 | |

The famous scene of the fire at Sanjō Palace, with a sequence of battle and barbarism at the foot of the scroll (Sanjō Palace fire scroll) | |

| Artist | Unknown |

| Completion date | Second half of the 13th century |

| Medium |

|

| Movement | Yamato-e |

| Subject | Heiji rebellion |

| Designation | National Treasure |

| Location | |

The Heiji Monogatari Emaki (平治物語絵巻, "The Tale of Heiji Emaki", or sometimes "The Tale of Heiji Ekotoba"; also translated as the "Heiji Rebellion Scrolls") is an emakimono or emaki (painted narrative handscroll) from the second half of the 13th century, in the Kamakura period of Japanese history (1185–1333). An illuminated manuscript, it narrates the events of the Heiji rebellion (1159–1160) between the Taira and Minamoto clans, one of several precursors to the broader Genpei War (1180–1185) between the same belligerents.

Both the author and the sponsor of the work remain unknown, and its production probably spanned several decades. Nowadays, only three original scrolls and a few fragments of a fourth remain; they are held by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum, Tokyo, and the Tokyo National Museum. The civil wars for the domination of Japan at the end of the Heian period, which ended with the victory of the Minamoto clan in the Genpei War, had a strong effect on the course of history in Japan. They have also been illustrated in many artworks, including the Heiji Monogatari Emaki, which has inspired many artists up until modern times.

The paintings in the work, in the Yamato-e style, are distinguished by both the dynamism of lines and movement and the vivid colours, as well as a realistic impetus characteristic of the arts of the Kamakura period. Cruelty, massacres and barbarities are also reproduced without any attenuation. The result is a "new style particularly suited to the vitality and confidence of the Kamakura period".[1] In several scrolls, long painted sequences introduced by short calligraphy passages are carefully composed in such a way as to create the tragic and the epic, such as the passage of the fire at Sanjō Palace, deeply studied by art historians.

Background[edit]

Emakimono arts[edit]

Originating in Japan in the sixth or seventh century through trade with the Chinese Empire, emakimono art spread widely among the aristocracy in the Heian period. An emakimono consists of one or more long rolls of paper narrating a story through Yamato-e texts and paintings. The reader discovers the story by progressively unrolling the scroll with one hand while rewinding it with the other hand, from right to left (according to the then horizontal writing direction of Japanese script), so that only a portion of text or image of about 60 cm (24 in) is visible.[2]

The narrative of an emakimono assumes a series of scenes, the rhythm, composition and transitions of which are entirely the artist's sensitivity and technique. The themes of the stories were very varied: illustrations of novels, historical chronicles, religious texts, biographies of famous people, humorous or fantastic anecdotes, etc.[2]

The Kamakura period, the advent of which followed a period of political turmoil and civil wars, was marked by the coming to power of the warrior class (the samurai). Artistic production was very strong, and more varied themes and techniques than before were explored,[3] signalling the "golden age" of emakimono (the 12th and 13th centuries).[4] Under the impetus of the new warrior class in power, emakimono evolved towards a more realistic and composite pictorial style.[5] Paintings of military and historical chronicles were particularly appreciated by the new ruling warrior class; ancient documents identify many emakimono on these subjects, including the Hōgen Monogatari Emaki (no longer extant), which recounted the Hōgen rebellion, the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba on the Mongol invasions, and of course the emakimono the subject of the present article.[6] According to Miyeko Murase, the epic battles transcribed in those emakimono must have strongly marked the minds of the Japanese, because the artists had made the battle theme enduring.[7]

The Heiji rebellion[edit]

The work describes the Heiji rebellion (1159–1160), one of the episodes of the historical transition period that saw Japan enter the Kamakura period and the Middle Ages: the Imperial Court lost all political power in favour of the feudal lords led by the shogun. During this transition, the authority of the emperors and the Fujiwara regents weakened due to corruption, the growing independence of local chiefs (daimyos), starvation and even superstition, so that the two main clans of the time vied for control of the state: the Taira clan and the Minamoto clan.[8]

Relations between the two clans deteriorated and political plots were asserted, so much so that in early 1160, the Minamoto clan attempted a coup by besieging Sanjō Palace in Kyoto to kidnap Retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa and his son Emperor Nijō. It was the start of the Heiji rebellion. The Taira, led by Taira no Kiyomori, hastily gathered its strength to retaliate; it took the advantage and decimated the rival clan, except for the young children. Ironically, among these children spared was Minamoto no Yoritomo who, a generation later in the Genpei War (1180–1185), would avenge his father and take control of all of Japan, establishing the political domination of the warriors in the new Kamakura period, from which the emakimono dates.[8][9]

The Heiji rebellion, famous in Japan, has been the subject of many literary adaptations, in particular The Tale of Heiji (平治物語, Heiji monogatari) from which the emakimono is directly inspired. The rivalries of clans, wars, personal ambitions and political intrigue amid social change and radical policies have made the Heiji rebellion an epic subject par excellence.[10][11] Indeed, this type of bloody, rhythmic storytelling is particularly suitable for emakimono.[12]

Description[edit]

Today, only three scrolls of the original emakimono remain, narrating the rebellion passages corresponding to the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, thirteenth and the beginning of the fourteenth chapters in The Tale of Heiji. According to Dietrich Seckel,[13] the original version probably had between ten and fifteen chapters, covering the thirty-six chapters of The Tale. Period fragments of a fourth scroll also exist, as well as later copies of a fifth.[7]

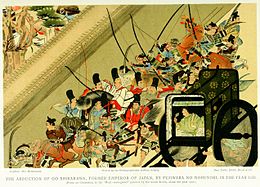

The first scroll, measuring 41.2 cm (16.2 in) by 730.6 cm (287.6 in), is at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; two sections of texts framing a long painting are taken from the third chapter of The Tale and relate the burning of Sanjō Palace by Fujiwara no Nobuyori (an ally of the Minamoto clan) and Minamoto no Yoshitomo.[14] The whole scene, cruel and pathetic, is built around the fire, bloody fighting around the palace, and the pursuit and arrest of Retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa. Nobles of the court, including women, were for the most part savagely killed by guns, fire or horses.[15]

The second scroll, 42.7 cm (16.8 in) by 1,011.7 cm (398.3 in), is at the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum in Tokyo; it includes three short texts from chapters four, five and six of The Tale.[14] The scroll opens with a Minamoto war council about Shinzei (Fujiwara no Michinori), an enemy who fled the palace. Alas, the latter commits suicide in the mountains around Kyoto and his body is found by Minamoto no Mitsuyasu's men, who behead him to bring back his head as a trophy. Clan leaders then visit Mitsuyasu's home to verify Shinzei's death and return to Kyoto showing off his head.[16]

The third scroll, 42.3 cm (16.7 in) by 951 cm (374 in), is kept at the Tokyo National Museum. Composed of four paintings and four portions of texts taken from chapter thirteen of The Tale, it depicts another famous moment of the Heiji rebellion: the escape of the young Emperor Nijō, disguised as a woman, followed by that of Bifukumon-in (wife of the late Emperor Toba).[14] Under the cover of night and with the help of his followers, his escort managed to escape the Minamoto guards and to join Taira no Kiyomori in Rokuhara (his men however failed to bring back the shinkyō, or sacred mirror). The final scenes offer a view of the Taira stronghold and the splendour of their army as Nobuyori is stunned when he discovers the escape.[17]

The fourteen fragments of the fourth scroll, scattered in various collections, are about the Battle of Rokuhara: Minamoto no Yoshitomo attacks the stronghold of the Taira, but he is defeated and must flee to the east of the country.[18][19] Although the composition of this scroll is very similar to that of the other scrolls, it cannot be said with certainty that all of the fragments belong to the original work, as there are slight stylistic variations.[15]

Several copies of the original four scrolls remain, as well as copies of a fifth, which is entirely lost: the battle of the Taiken Gate, without text, narrating the Taira's assault on the Imperial Palace where the Minamoto warriors had entrenched themselves.[20]

The first scroll, now in Boston, depicting the burning of the Sanjō Palace, is regularly described as one of the masterpieces of Japanese emakimono art and of military painting of the world in general.[11][21][22] The second, or Shinzei, scroll is listed in the Register of Important Cultural Property,[23] and the third scroll, relating Emperor Nijō's flight, is included in the Register of National Treasures of Japan.[24]

Dating, author and sponsor[edit]

Very little information is available about the realisation of the original scrolls, and the events explaining their condition and partial destruction. The artist(s) remain unknown; the work was previously attributed to the supposed 14th century painter Sumiyoshi Keion, but that attribution has been deprecated since the second half of the 20th century, as the very existence of that painter is doubtful.[10][25]

The sponsor is no better known, but was probably a relative of the Minamoto clan, ruler of Japan at the time the emakimono was made, as suggested by the brilliant representation of the Minamoto warriors.[11][26]

According to estimates and stylistic comparisons, the creation of the work dates from the middle and second half of the 13th century, probably between the 1250s and the 1280s.[24][27] The pictorial proximity between all the scrolls shows that they probably come from the same workshop painters, but slight variations tend to confirm that the preparation took place over several decades during the second half of the 13th century, without the reason for such a long period of creation being known.[28][29]

Fragments of the fourth or Battle of Rokuhara scroll, a little more recent and slightly different in style, may belong either to the original work or to an old copy from the Kamakura period according to art historians, but again the true position is uncertain.[30]

Style and composition[edit]

The pictorial style of the Heiji Monogatari Emaki is Yamato-e,[28] a Japanese painting movement (as opposed to Chinese styles) that peaked during the Heian and Kamakura periods. Artists of the Yamato-e style, a colourful and decorative everyday form of art, expressed in all their subjects the sensitivity and character of the people of the Japanese archipelago.[31]

The work belongs mainly to the otoko-e ("painting of men") genre of Yamato-e, typical of epic tales or religious legends, by emphasising the freedom of ink lines and the use of light colours leaving portions of paper bare.[32] The dynamism of the lines is particularly evident in the crowds of people and soldiers. However, and as in the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, it is combined with the onna-e (or "painting of women") court style of Yamato-e, especially in the choice of more vivid colours for certain details such as clothing, armour and flames. The scene of the fire is also reminiscent of that of the Ōtenmon gate in the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba, due to its similar composition.[33] The colour in the work is applied mainly using the tsukuri-e technique characteristic of onna-e: a first sketch of the outlines is made, then the colour is added in solid form, and finally the outlines are redrawn in ink over the paint. This mixture of onna-e and otoko-e, tangible in other works such as the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki, is typical of the emakimono style from the beginning of the Kamakura period, with rich colours using bright pigments alongside more pastel shades, while the lines remain dynamic and expressive, but less free than in older otoko-e paintings. The military in power at the time particularly appreciated colourful and dynamic historical and military chronicles.[14][34][35]

A new desire for realism, notable in several aspects of the Heiji Monogatari Emaki, also marked the art of portrayal of Kamakura warriors: in this work, the combat scenes are expressed in a raw and brutal way, showing the suffering and death in the glowing flames and blood.[15] In particular, the painting of the attack on the Sanjō Palace depicts soldiers slaughtering aristocrats and displaying their heads on top of lances.[36] Christine Shimizu underlines the realism in the representation of the characters: "The painter approaches the faces, the attitudes of the characters as well as the movements of the horses with a surprising sense of realism, proving his ability to incorporate the techniques of nise-e in complex scenes" (nise-e was a realistic style of portraiture in vogue at the time).[37] The realistic tendency is also found in most of the alternative versions of the work.[12] On the other hand, the sets are most often minimalist to keep the reader's attention on the action and the suspense, without distraction.[38]

The emakimono is also distinguished by two types of classical emakimono arts composition techniques. On the one hand, continuous compositions make it possible to represent several scenes or events in the same painting, without a precise border, in order to favour a fluid pictorial narration; this is the case with the first or Sanjō Palace fire scroll and the fourth or Battle of Rokuhara scroll. On the other hand, the alternating compositions bring together calligraphy and illustrations, the paintings then aiming to capture particular moments of the story; this is the case with the other scrolls as well as the copies of the now lost Battle of Taiken Gate scroll.[39] The painter thus manages to vary with accuracy the rhythm of the narration throughout the emakimono, for example making passages of strong tensions succeed more peaceful scenes, such as the arrival of Emperor Nijō among the Taira after his perilous flight.[38]

The long painted sequences with continuous compositions, sometimes interspersed with short calligraphy, make possible the intensification of the painting to its dramatic climax, in the remarkable scene of the fire at the Sanjō Palace:[40] the reader first discovers the flight of the Emperor's troops, then more and more violent fighting leading up to the confusion around the fire – the summit of the composition where the density of the characters only fades in front of the ample volutes of smoke – and then finally the scene calms down with the encirclement of the Emperor's chariot and a soldier who moves away peacefully towards the left.[7] The transition to the scene of the fire is effected by means of a wall of the Palace, which divides the emakimono by long diagonals over almost its entire height, creating an effect of suspense and different narrative spaces with great fluidity.[41] For art historians, the mastery of composition and rhythm, evident in continuous paintings, as well as the care given to colours and lines, make this scroll one of the most admirable to have survived from the Kamakura period.[22][28]

The emakimono also displays some innovations of composition for the groups of characters, by arranging them in triangles or rhombuses. This approach makes it possible to take advantage of the reduced height of the scrolls to represent battles by interweaving geometric shapes according to the needs of the artist.[1][37]

Historiographical value[edit]

The Heiji Monogatari Emaki provides a glimpse into the unfolding of historical events of the Heiji rebellion, and, more importantly, significant testimony as to the life and culture of the samurai. The first or Sanjō Palace fire scroll shows a wide range of this military class: clan chiefs, horse archers, infantry, monk-soldiers, imperial police (kebiishi) ... The weapons and armour depicted in the emakimono are also very realistic, and as a whole the work testifies to the still predominant role of the mounted yumi archer, and not the katana infantryman, for the samurai of the 12th century.[42] The beauty of the luxurious harnesses of the Heian period is also underlined by the work;[28] the contrast between the harnesses and the cruel and vulgar squadron is interesting, in particular because the texts in the work deal very little with this subject.[43] Additionally, some aspects of period military uniforms can only be understood today through the paintings.[36] On the other hand, the texts provide little historiographical information because of their brevity and, sometimes, their inadequate or inaccurate descriptions of the paintings.[44]

The depiction of Sanjō Palace shortly before its destruction provides an important example of the ancient shinden-zukuri architectural style that developed in the Heian period away from the Chinese influences in vogue during the Nara period. The long corridors of the Palace lined with panels, windows or blinds, the raised wooden verandas and the roofs covered with thin layers of Japanese cypress bark (桧 皮 葺, hiwada-buki) are characteristic of the style.[45]

The emakimono has also been a source of inspiration for various artists, first and foremost those who took up the theme of the Heiji rebellion on a screen or fan, including Tawaraya Sōtatsu[46] and Iwasa Matabei.[47] In paintings of a major military subject in Japan, many depictions of battle are unsurprisingly inspired by the work. So, for example, the Taiheiki Emaki of the Edo period depicts very similar arrangements of groups of warriors and postures of the characters.[48] Additionally, studies indicate that the painter Kanō Tan'yū was inspired, among other things, by the Heiji Monogatari Emaki in creating the paintings of the Battle of Sekigahara in his Tōshō Daigongen Engi (17th century) (according to Karen Gerhart, the goal was symbolically to associate the Tokugawa shogunate with the Minamoto clan, the first shoguns of Japan).[49] Similar comments apply to Tani Bunchō in relation to the Ishiyama-dera Engi Emaki.[50] Indeed, the fourth or Battle of Rokuhara scroll was the most imitated and popular in Japanese painting, so much so that in the Edo period it became a classic motif of battle paintings.[51]

Finally, Teinosuke Kinugasa drew some inspiration from the work for his film Gate of Hell (Jigokumon).[52]

Provenance[edit]

The whole of the original Heiji Monogatari Emaki was kept for a long time at the Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei, overlooking Kyoto, together with the emakimono, no longer extant, of The Tale of Hōgen.[53] During the 15th and the 16th centuries, the original scrolls were separated, but their history at that time is lost to modern times. In the 19th century, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, won the first or Sanjō Palace fire scroll through Okakura Kakuzō. The third or Flight to Rokuhara Scroll was acquired by the Tokyo National Museum from the Matsudaira clan in around 1926. Finally, the second or Shinzei scroll was acquired by the wealthy Iwasaki family, whose collection is preserved by the Seikadō Foundation (now the Seikadō Bunko Art Museum).[54]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b SNEZ, p. 3.

- ^ a b Kōzō Sasaki. "(iii) Yamato-e (d) Picture scrolls and books". Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Okudaira 1973, p. 32.

- ^ Shimizu 2001, pp. 193–196.

- ^ SNEZ, p. 1.

- ^ Okudaira 1973, p. 34.

- ^ a b c Murase 1996, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b Elisseeff 2001, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Reischauer, Edwin Oldfather (1997). Histoire du Japon et des Japonais: Des origines à 1945 [History of Japan and the Japanese: From the origins to 1945]. Points. Histoire (in French). Vol. 1. Translated by Dubreuil, Richard (3rd ed.). Paris: Seuil. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-2-02-000675-0.

- ^ a b Seckel & Hasé 1959, p. 213.

- ^ a b c Rabb 2000.

- ^ a b Lee, Cunningham & Ulak 1983, pp. 68–72.

- ^ Seckel & Hasé 1959, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d Iwao & Iyanaga 2002, pp. 945–946.

- ^ a b c SNEZ, p. 12.

- ^ SNEZ, pp. 9–10.

- ^ SNEZ, pp. 6–7, 11.

- ^ SNEZ, p. 2.

- ^ "Kokka / Rokuhara Battle Fragment from the Tale of Heiji Handscroll". The Asahi Shimbun. 15 March 2012.

- ^ Mason 1977, pp. 245–249.

- ^ Terukazu 1977.

- ^ a b Paine 1939, p. 29.

- ^ "重文 平治物語絵巻 信西巻". Seikadō Bunko Art Museum. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ a b Okudaira 1973, pp. 109–113.

- ^ Mason 1977, p. 165.

- ^ Seckel & Hasé 1959, p. 41.

- ^ Mason 1977, pp. 211, 253.

- ^ a b c d Terukazu 1977, pp. 95–98.

- ^ Mason 1977, p. 211.

- ^ Akiyama, Terukazu [in French] (September 1952). "平治物語絵六波羅合戦巻にっいて" [About the Battle of Rokuhara scroll of the Heiji Monogatari Emaki]. Yamato Bunka (in Japanese): 1–11.

- ^ Ienaga, Saburō (1973). Painting in the Yamato style. The Heibonsha survey of Japanese art. Vol. 10. Weatherhill. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-8348-1016-7.

- ^ Okudaira 1973, p. 53.

- ^ Mason & Dinwiddie 2005, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Toda, Kenji (1935). Japanese Scroll Painting. University of Chicago Press. pp. 89–90.

- ^ Okudaira 1973, p. 57.

- ^ a b "Heiji Scroll: Interactive Viewer". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ a b Shimizu 2001, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Seckel & Hasé 1959, p. 44.

- ^ Mason 1977, pp. 212, 250.

- ^ Grilli 1962, p. 7.

- ^ Mason 1977, p. 219–220.

- ^ Charles, Victoria; Sun Tzu (2012). L'art de la guerre [The Art of War] (in French). Parkstone International. p. 78. ISBN 9781781602959.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2001). Ashigaru 1467-1649. Osprey Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 9781841761497.

- ^ Varley, H. Paul (1994). Warriors of Japan: As Portrayed in the War Tales. University of Hawaii Press. p. 68. ISBN 9780824816018.

- ^ Coaldrake, William Howard (1996). Architecture and authority in Japan. Routledge. pp. 84–87. ISBN 9780415106016.

- ^ Murase, Miyeko (1967). "Japanese Screen Paintings of the Hōgen and Heiji Insurrections". Artibus Asiae. 29 (2/3): 193–228. doi:10.2307/3250273. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3250273.

- ^ Mason 1977, p. 147.

- ^ Murase, Miyeko (1993). "The "Taiheiki Emaki": The Use of the Past". Artibus Asiae. 53 (1/2): 262–289. doi:10.2307/3250519. JSTOR 3250519.

- ^ Gerhart, Karen M. (1999). The Eyes of Power: Art and Early Tokugawa Authority. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 9780824821784.

- ^ Mason 1977, p. 205.

- ^ Mason 1977, pp. 287–295, 305.

- ^ Sieffert, René. "Heiji monogatari". Encyclopædia Universalis (in French).

- ^ "Rouleau illustré du Dit de Heiji (bien impérial de Rokuhara)" [Heiji Monogatari Emaki (Imperial treasure of Rokuhara)] (in French). National Institutes for Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Mason 1977, pp. 196–201.

Bibliography[edit]

- Elisseeff, Danielle [in French] (2001). Histoire du Japon: entre Chine et Pacifique [History of Japan: Between China and the Pacific] (in French). Monaco: Éditions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-04096-7.

- Grilli, Elise (1962). Rouleaux peints japonais [Japanese Painted Scrolls] (in French). Translated by Requien, Marcel. Arthaud.

- Iwao, Seiichi; Iyanaga, Teizo (2002). Dictionnaire historique du Japon [Historical Dictionary of Japan] (in French). Vol. 1–2. Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 978-2-7068-1633-8.

- Lee, Sherman E.; Cunningham, Michael R.; Ulak, James T. (1983). Reflections of Reality in Japanese Art. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-910386-70-8.

- Mason, Penelope E. (1977). A Reconstruction of the Hōgen Heiji Monogatari Emaki. Outstanding dissertations in the fine arts. New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 0824027094.

- Mason, Penelope E.; Dinwiddie, Donald (2005). History of Japanese Art. Pearson-Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-117601-0.

- Minamoto, Toyomune; Miya, Tsugio; Tanaka, Ichimatsu (1975). 北野天神縁起 [Kitano Tenjin Engi]. Shinshū Nihon emakimono zenshū (in Japanese). Vol. 9. Kadokawa Shoten.

- Murase, Miyeko (1996). L'Art du Japon [The Art of Japan]. La Pochothèque series (in French). Paris: Éditions LGF - Livre de Poche. ISBN 2-253-13054-0.

- Okudaira, Hideo (1973). Narrative picture scrolls. Arts of Japan series. Vol. 5. Translated by Ten Grotenhuis, Elizabeth. Weatherhill. ISBN 978-0-8348-2710-3.

- Paine, Robert Treat (1939). Ten Japanese Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Japan Society of New York. pp. 29–34.

- Rabb, Theodore T. (Winter 2000). "The painter of the Heiji Monogatari Emaki". The Quarterly Journal of Military History. 12 (2): 50–53.

- Seckel, Dietrich; Hasé, Akihisa (1959). Emaki: L'art classique des rouleaux peints japonais [the classic art of Japanese painted scrolls]. Translated by Guerne, Armel. Delpire.

- Shimizu, Christine (2001). L'Art japonais [Japanese Art]. Tout l'art series (in French). Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-013701-2.

- Terukazu, Akiyama (1977). La peinture japonaise [Japanese Painting]. Les Trésors de l’Asie, Skira-Flammarion (in French). Vol. 3. Skira. pp. 95–98. ISBN 978-2-605-00094-4.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Heiji Monogatari Emaki at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Heiji Monogatari Emaki at Wikimedia Commons