Generation of the '30s

The Generation of the '30s (Greek: Γενιά του 1930) was a group of Greek writers, poets, artists, intellectuals, critics, and scholars who made their debut in the 1930s and introduced modernism in Greek art and literature. The Generation of the '30s is also cited as a social movement.[1] The previous Medieval and post-Byzantine Greek eras, which glorified religion, Jesus, and the certainty of Enlightenment thinking, were rejected by modernism. Elements of surrealism and utopianism were introduced in efforts to renew contemporary literature. Most notable among the Generation of the ‘30s is Giorgos Seferis, a Greek poet of the 20th century who instigated the turning point into modernity with surrealism in his poetry. After the Balkan Wars and the disastrous Greco-Turkish War of 1922, literature could no longer boast nationalistic aspirations of the previous generation.[2] Thus, there was a need to establish a new dogma, or Greekness (Ελληνικότητα), that would aestheticize Hellenocentric opinions, attitudes, and symbols, and foster a new national identity.[3] The Generation of the ‘30s enacted this by publishing various art and literature that were autonomous from other foreign models, and institutionalized modern literature to open up new perspectives and explore new ways to understand Greekness.

Literature of the 1920s[edit]

Modernism had a late arrival in Greece. While the modernist movement began to rapidly transform Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was not until the 1930s that Greece witnessed the introduction of a new set of practices and formal innovations.[4] The 1920s offered a pessimistic attitude and were largely dismissive of society or life. Because of the numerous negative historical events that occurred, such as the Greco-Turkish War and the subsequent refugee influx, high unemployment rates, and domestic instability, literature lacked optimism and a positive worldview. Kostas Karyotakis, a Greek poet of the 1920s, is often cited as one of the first poets to use iconoclastic themes. His poems talk about nature, are embedded with imagery, and have traces of expressionism and surrealism. At first, his cosmopolitan outlook was rejected; however, it was his perspective that eventually shaped modern Greek poetry and created a path for the Generation of the '30s to follow. In 1929, Yorgos Theotokas published a major essay entitled Free Spirit (Ελεύθερο Πνέυμα), which became the manifesto of the flourishing Generation of the '30s, exemplified a desire to modernize Greek literature. He stated that manifesting modernism in poetry was not enough; a new literature required “discussion of ideas, and authentic theatre and an authentic novel.”[1]

History[edit]

Post World War I[edit]

When Greece emerged victorious from World War I, it was rewarded with territorial acquisitions, specifically Western Thrace (Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine), Eastern Thrace, and the Smyrna area (Treaty of Sèvres). As a result, national identity was heightened and a concept called the Megali Idea (Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, “Great Idea”) was developed. It exhibited pride in Greece's success in World War I. It also expressed the goal of acquiring more ethnic Greek-inhabited territories and expanding the Greek language and culture among them. In many ways, the Megali Idea fused Hellenism with Byzantine/Orthodox traditionalism (Thomas, 1996, p. 102). It dreamt of creating a “second Byzantium” that would incorporate Greek-speakers into a Greater Greece.[5] The unification of all Greeks in one state would celebrate their “temporal continuity,” proclaim their “territorial integrity,” and serve as a “populist cause to mobilize the masses.”[1] This ideology is consistent to understandings of modernism. The deliberate rejection of a disintegrated previous Greece and the introduction of a new Greece that would emphasize consolidation reflected a new ethnic identity. Most importantly, the Megali Idea allowed the experience of shared identity of Hellenism and brought Greeks inside and outside of the state together. Ioannis Kolettis, a Greek politician who is credited with conceiving the Megali Idea, asserted that “the Greek kingdom is not the whole of Greece, but only a part, the smallest and poorest part. A native is not only someone who lives within this Kingdom but also…in any land associated with Greek history or the Greek race.” In essence, this immense ethnic pride gave rise to an adhered emphasis on innovation and experimentation of the Greek state.

The collapse of the Megali Idea[edit]

Following Greece's loss in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919 to 1922, gains were largely undone. Greeks experienced this event as a “national trauma of apocalyptic proportions”[1] because it undermined the Greek force's abilities to gain control of areas in Asia Minor. Following the defeat of the Greco-Turkish War was the rout of the Hellenic army, the destruction of Smyrna, and the population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Ultimately, there was a re-evaluation of national identity which prompted the disintegration of the Megali Idea in Greek society. A new national identity, referred to as Greekness, started to emerge in literary works. Unlike the Hellenism of the purists, which sought conformity to traditional rules or structures, Greekness sought to synthesize all of the works which have been produced by the Greeks.[1] Based on anthologies of the period, politics were suppressed, and resultantly there was a focus on the aestheticization of space, the handling of unpleasant memories, and the inclusion and exclusion of foreigners. It was an aesthetic that would combine the unique features of Greek language and culture and bond Greek people through their shared identity.

Notable works[edit]

Art[edit]

Under the influence of the 19th century School of Munich, art was conservative and romantic. However, the Generation of the 30s sought to introduce more abstract, surrealistic, and magical realism elements into their art. Often representing impressionist features, academism, realism, genre painting, upper-middle-class portraiture, still life, and landscape painting inspired by revolutionary as well as the country's geography and history. A key member in the introduction of surrealism was an artist, poet, and essayist Nikos Engonopoulos. He created art that was inspired by Greek subjects, colors, and symbols. Some of his most notable pieces include “Civil War” and “Hermes Waiting.” Yannis Tsarouchis, a Greek artist who was a part of the “Armos” art group along with Engonopoulos, produced abstract, idealized art. His most notable pieces include “The Four Seasons” and “The Forgotten Army.” Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, recognized as the leading Greek cubist artist, produced collage-like art which allows the viewer to see his work in different angles and perspectives. After the 50s and 60s, his style became more prismatic with the use of brilliant colors and patterns. His most notable pieces include “Memories of Hydra” and “Mystras.” Spyros Vassiliou, an impressionistic artist who prominently used magical realism in his paintings, painted patriotic subjects. His most notable pieces include “Small World of Webster Street” and “25th of March.”

Literature[edit]

The Generation of the '30s produced novels including Life in the Tomb by Stratis Myrivilis, a journal of life in the trenches in WWI; Eroica by Kosmas Politis, which is about the first encounter of a group of schoolboys with love and death; and Argo by Yiorgos Theotokas, which deals with the struggles young students experienced during pre-WWII Greece. Theotokas also wrote two essays entitled Free Spirit (1929) and The Lost Center (1961). Free Spirit demands closer ties with its culture and Europe through the introduction of utopian themes of departure and freedom in literature. The Lost Center expresses nostalgia for a homecoming.[6] For Theotokas, self-motivation, progress, and open frontiers were crucial in the re-evaluation and modernization of literature.

Folk tradition[edit]

To maintain its cultural cohesion and continuity, Greekness was embedded in folk tradition. For example, the center of the Generation of the ‘30s’ artistic canon was placed on the Karagiozis players of the shadow theatre. These shadow puppets performed scenes that addressed issues of identity and Greekness. They also performed the songs of Rebetiko (Ρεμπέτικο) and the Greek blues which focused on popular and marginal groups. They dealt with “the life of urban subculture whose values and customs were outside the mainstream of Greek societies.”[7] Rebetiko specifically talked about the archetypal experiences of urbanism, which was accompanied by the nostalgia for the loss of rural life.

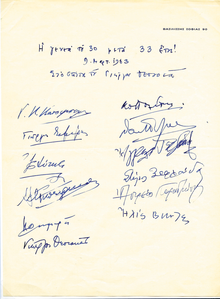

Notable members[edit]

The most important members of the Generation of the '30s movement are the following writers:

- Giorgos Seferis: Greek poet and diplomat

- Odysseas Elytis: Greek poet and art critic

- Andreas Embirikos Greek poet who is considered as the chief representative of Surrealism in Greek literature

- Nikos Engonopoulos: Greek artist who is considered as the main representative of Surrealism in Greek art

- Giannis Ritsos: Greek poet and left-wing activist during WWII

- Nikiforos Vrettakos: Greek poet

- D.I. Antoniou: seafaring Greek poet

Legacy[edit]

The Generation of the '30s and their introduction of Demotic Greek gave rise to the Modern Greek language that is spoken today. Without the influences from the Generation of the '30s, the modernism found in the Greek language and literature would not have been present today. Most importantly, the elements of modernism that are found in art today are often cited to be influenced from Greek art. For example, the art of the Archaic period in Greece features a lot of abstract and geometric artwork. It is very similar to later artistic styles such as cubism, surrealism, expressionism. These movements are often cited to have gained inspiration from the artwork of Engonopoulos.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Jusdanis, G. (1992). Belated Modernity and Aesthetic Culture: Inventing National Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 78.

- ^ Sofroniou, A. (2015). Social Sciences and Philology. Lulu. p. 415.

- ^ Tziovas, D.; Bien, P. (1997). Greek Modernism and Beyond: Essays in Honor of Peter Bien. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 43.

- ^ Eysteinsson, A.; Liska, V. (2007). Modernism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. p. 991.

- ^ Thomas, R. G. (1996). The South Slav Conflict: History, Religion, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 102.

- ^ Tziovas, D.; Bien, P. (1997). Greek Modernism and Beyond: Essays in Honor of Peter Bien. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 26.

- ^ Kefala, E. (2007). Peripheral (Post) Modernity: The Syncretist Aesthetics of Borges, Piglia, Kalokyris and Kyriakidis. New York: Peter Lang. p. 61.