Battle of Ceresole

| Battle of Ceresole | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian War of 1542–1546 | |||||||

Bataille de Cérisoles, 14 avril 1544 (oil on canvas by Jean-Victor Schnetz, 1836–1837) depicts François de Bourbon at the end of the battle. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of France |

Holy Roman Empire Spain | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| François de Bourbon | Alfonso d'Avalos | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~11,000–13,000 infantry, ~1,500–1,850 cavalry, ~20 guns |

~12,500–18,000 infantry, ~800–1,000 cavalry, ~20 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~1,500–2,000+ dead or wounded |

~5,000–6,000+ dead or wounded, ~3,150 captured | ||||||

Location within Alps | |||||||

The Battle of Ceresole ([tʃereˈzɔːle]; also Cérisoles) took place on 14 April 1544, during the Italian War of 1542–1546, outside the village of Ceresole d'Alba in the Piedmont region of Italy. A French army, commanded by François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien, defeated the combined forces of the Holy Roman Empire and Spain, commanded by Alfonso d'Avalos d'Aquino, Marquis del Vasto. Despite having inflicted substantial casualties on the Imperial troops, the French subsequently failed to exploit their victory by taking Milan.

Enghien and d'Avalos had arranged their armies along two parallel ridges; because of the topography of the battlefield, many of the individual actions of the battle were uncoordinated. The battle opened with several hours of skirmishing between opposing bands of arquebusiers and an ineffectual artillery exchange, after which d'Avalos ordered a general advance. In the center, Imperial landsknechts clashed with French and Swiss infantry, with both sides suffering terrific casualties. In the southern part of the battlefield, Italian infantry in Imperial service were harried by French cavalry attacks and withdrew after learning that the Imperial troops of the center had been defeated. In the north, meanwhile, the French infantry line crumbled, and Enghien led a series of ineffectual and costly cavalry charges against Spanish and German infantry before the latter were forced to surrender by the arrival of the victorious Swiss and French infantry from the center.

Ceresole was one of the few pitched battles during the latter half of the Italian Wars. Known among military historians chiefly for the "great slaughter" that occurred when columns of intermingled arquebusiers and pikemen met in the center, it also demonstrates the continuing role of traditional heavy cavalry on a battlefield largely dominated by the emerging pike and shot infantry.

Prelude[edit]

The opening of the war in northern Italy had been marked by the fall of Nice to a combined Franco-Ottoman fleet in August 1543; meanwhile, Imperial-Spanish forces had advanced from Lombardy towards Turin, which had been left in French hands at the end of the previous war in 1538.[1] By the winter of 1543–1544, a stalemate had developed in the Piedmont between the French, under the Sieur de Boutières, and the Imperial army, under d'Avalos.[2] The French position, centered on Turin, reached outward to a series of fortified towns: Pinerolo, Carmagnola, Savigliano, Susa, Moncalieri, Villanova, Chivasso, and a number of others; d'Avalos, meanwhile, controlled a group of fortresses on the periphery of the French territory: Mondovì, Asti, Casale Monferrato, Vercelli, and Ivrea.[3] The two armies occupied themselves primarily with attacking each other's outlying strongholds. Boutières seized San Germano Vercellese, near Vercelli, and laid siege to Ivrea; d'Avalos, meanwhile, captured Carignano, only fifteen miles south of Turin, and proceeded to garrison and fortify it.[4]

As the two armies returned to winter quarters, Francis I of France replaced Boutières with François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien, a prince with no experience commanding an army.[5] Francis also sent additional troops to the Piedmont, including several hundred heavy cavalry, some companies of French infantry from Dauphiné and Languedoc, and a force of quasi-Swiss from Gruyères.[6] In January 1544, Enghien laid siege to Carignano, which was defended by Imperial troops under the command of Pirro Colonna.[7] The French were of the opinion that d'Avalos would be forced to attempt a relief of the besieged city, at which point he could be forced into a battle; but as such pitched battles were viewed as very risky undertakings, Enghien sent Blaise de Lasseran-Massencôme, seigneur de Montluc, to Paris to ask Francis for permission to fight one.[8] Montluc apparently convinced Francis to give his assent—contingent on the agreement of Enghien's captains—over the objections of the Comte de St. Pol, who complained that a defeat would leave France exposed to an invasion by d'Avalos's troops at a time when Charles V and Henry VIII of England were expected to attack Picardy.[9] Montluc, returning to Italy, brought with him nearly a hundred volunteers from among the young noblemen of the court, including Gaspard de Coligny.[10]

D'Avalos, having waited for the arrival of a large body of landsknechts dispatched by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, set off from Asti towards Carignano.[11] His total force included 12,500–18,000 infantry, of which perhaps 4,000 were arquebusiers or musketeers; he was only able to gather about 800–1,000 cavalry, of which less than 200 were gendarmes.[12] D'Avalos recognized the relative weakness of his cavalry, but considered it to be compensated by the experience of his infantry and the large number of arquebusiers in its ranks.[13]

Enghien, having learned of the Imperial advance, left a blocking force at Carignano and assembled the remainder of his army at Carmagnola, blocking d'Avalos's route to the besieged city.[14] The French cavalry, shadowing d'Avalos's movements, discovered that the Imperial forces were headed directly for the French position; on 10 April, d'Avalos occupied the village of Ceresole d'Alba, about five miles (8 km) southeast of the French.[15] Enghien's officers urged him to attack immediately, but he was determined to fight on ground of his own choosing; on the morning of 14 April, the French marched from Carmagnola to a position some three miles (5 km) to the southeast and awaited d'Avalos's arrival.[16] Enghien and Montluc felt that the open ground would give the French cavalry a significant tactical advantage.[17] By this point, the French army consisted of around 11,000–13,000 infantry, 600 light cavalry, and 900–1,250 heavy cavalry; Enghien and d'Avalos each had about twenty pieces of artillery.[18] The battle came at a fortunate time for Enghien, as his Swiss troops were—as they had before the Battle of Bicocca—threatening to march home if they were not paid; the news of the impending battle restored some calm to their ranks.[19]

Battle[edit]

Dispositions[edit]

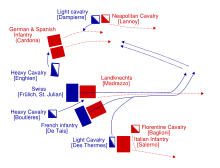

Enghien's troops were positioned along the crest of a ridge that was higher in the center than on either side, preventing the wings of the French army from seeing each other.[20] The French army was divided into the traditional "battle", "vanward", and "rearward" corps, corresponding to the center and right and left wings of the French line.[21] On the far right of the French position was a body of light cavalry, consisting of three companies under Des Thermes, Bernadino, and Mauré, with a total strength of around 450–500 men.[22] To their left was the French infantry under De Tais, numbering around 4,000, and, farther to the left, a squadron of 80 gendarmes under Boutières, who was nominally the commander of the entire French right wing.[23] The center of the French line was formed by thirteen companies of veteran Swiss, numbering about 4,000, under the joint command of William Frülich of Soleure and a captain named St. Julian.[24] To their left was Enghien himself with three companies of heavy cavalry, a company of light horse, and the volunteers from Paris—in total, around 450 troopers.[25] The left wing was composed of two columns of infantry, consisting of 3,000 of the recruits from Gruyères and 2,000 Italians, all under the command of Sieur Descroz.[26] On the extreme left of the line were about 400 mounted archers deployed as light cavalry; they were commanded by Dampierre, who was also given command of the entire French left wing.[27]

The Imperial line formed up on a similar ridge facing the French position.[28] On the far left, facing Des Thermes, were 300 Florentine light cavalry under Rodolfo Baglioni; flanking them to the right were 6,000 Italian infantry under Ferrante Sanseverino, Prince of Salerno.[29] In the center were the 7,000 landsknechte under the command of Eriprando Madruzzo.[30] To their right was d'Avalos himself, together with the small force of about 200 heavy cavalry under Carlo Gonzaga.[31] The Imperial right wing was composed of around 5,000 German and Spanish infantry under Ramón de Cardona; they were flanked, on the far right, by 300 Italian light cavalry under Philip de Lannoy, Prince of Sulmona.[32]

| French (François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien) |

Spanish–Imperial (Alfonso d'Avalos d'Aquino, Marquis del Vasto) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | Strength | Commander | Unit | Strength | Commander |

| Light cavalry | ~400 | Dampierre | Neapolitan light cavalry | ~300 | Philip de Lannoy, Prince of Sulmona |

| Italian infantry | ~2,000 | Descroz | Spanish and German infantry | ~5,000 | Ramón de Cardona |

| Gruyères infantry | ~3,000 | Descroz | |||

| Heavy cavalry | ~450 | François de Bourbon, Count of Enghien | Heavy cavalry | ~200 | Carlo Gonzaga |

| Swiss | ~4,000 | William Frülich of Soleure and St. Julian | Landsknechte | ~7,000 | Eriprando Madruzzo |

| Heavy cavalry | ~80 | Sieur de Boutières | |||

| French (Gascon) infantry | ~4,000 | De Tais | Italian infantry | ~6,000 | Ferrante Sanseverino, Prince of Salerno |

| Light cavalry | ~450–500 | Des Thermes | Florentine light cavalry | ~300 | Rodolfo Baglioni |

Initial moves[edit]

As d'Avalos's troops, marching from Ceresole, began to arrive on the battlefield, both armies attempted to conceal their numbers and position from the other; Enghien had ordered the Swiss to lie on the ground behind the crest of the ridge, while only the left wing of the Imperial army was initially visible to the French.[33] D'Avalos sent out parties of arquebusiers in an attempt to locate the French flanks; Enghien, in turn, detached about 800 arquebusiers under Montluc to delay the Imperial advance.[34] The skirmishing between the arquebusiers continued for almost four hours; Martin Du Bellay, observing the engagement, described it as "a pretty sight for anyone who was in a safe place and unemployed, for they played off on each other all the ruses and stratagems of petty war."[35] As the extent of each army's position was revealed, Enghien and d'Avalos both brought up their artillery.[36] The ensuing cannonade continued for several hours, but had little effect because of the distance and the considerable cover available to the troops on both sides.[37]

The skirmishing finally came to an end when it seemed that Imperial cavalry would attack the French arquebusiers in the flank; Montluc then requested assistance from Des Thermes, who advanced with his entire force of light cavalry.[33] D'Avalos, observing the French movement, ordered a general advance along the entire Imperial line.[38] At the southern end of the battlefield, the French light cavalry drove Baglioni's Florentines back into Sanseverino's advancing infantry, and then proceeded to charge directly into the infantry column.[30] The Italian formation held, and Des Thermes himself was wounded and captured; but by the time Sanseverino had dealt with the resulting disorder and was ready to advance again, the fight in the center had already been decided.[39]

"A wholesale slaughter"[edit]

The French infantry—mostly Gascons—had meanwhile started down the slope towards Sanseverino.[30] Montluc, noting that the disorder of the Italians had forced them to a standstill, suggested that De Tais attack Madruzzo's advancing column of landsknechte instead; this advice was accepted, and the French formation turned left in an attempt to strike the landsknechte in the flank.[40] Madruzzo responded by splitting his column into two separate portions, one of which moved to intercept the French while the other continued up the slope towards the Swiss waiting at the crest.[41]

The pike and shot infantry had by this time adopted a system in which arquebusiers and pikemen were intermingled in combined units; both the French and the Imperial infantry contained men with firearms interspersed in the larger columns of pikemen.[42] This combination of pikes and small arms made close-quarters fighting extremely bloody.[43] The mixed infantry was normally placed in separate clusters, with the arquebusiers on the flanks of a central column of pikemen; at Ceresole, however, the French infantry had been arranged with the first rank of pikemen followed immediately by a rank of arquebusiers, who were ordered to hold their fire until the two columns met.[44] Montluc, who claimed to have devised the scheme, wrote that:

In this way we should kill all their captains in the front rank. But we found that they were as ingenious as ourselves, for behind their first line of pikes they had put pistoleers. Neither side fired till we were touching—and then there was a wholesale slaughter: every shot told: the whole front rank on each side went down.[45]

The Swiss, seeing the French engage one of the two columns of landsknechte, finally descended to meet the other, which had been slowly moving up the hillside.[46] Both masses of infantry remained locked in a push of pike until the squadron of heavy cavalry under Boutières charged into the landsknechts' flank, shattering their formation and driving them down the slope.[47] The Imperial heavy cavalry, which had been on the landsknechts' right, and which had been ordered by d'Avalos to attack the Swiss, recoiled from the pikes and fled to the rear, leaving Carlo Gonzaga to be taken prisoner.[48]

The Swiss and Gascon infantry proceeded to slaughter the remaining landsknechte—whose tight order precluded a rapid retreat—as they attempted to withdraw from the battlefield.[49] The road to Ceresole was littered with corpses; the Swiss, in particular, showed no mercy, as they wished to avenge the mistreatment of the Swiss garrison of Mondovì the previous November.[49] Most of the landsknechts' officers were killed; and while contemporary accounts probably exaggerate the numbers of the dead, it is clear that the German infantry had ceased to exist as a fighting force.[50] Seeing this, Sanseverino decided that the battle was lost and marched away to Asti with the bulk of the Italian infantry and the remnants of Baglioni's Florentine cavalry; the French light cavalry, meanwhile, joined in the pursuit of the landsknechts.[51]

Engagements in the north[edit]

On the northern end of the battlefield, events had unfolded quite differently. Dampierre's cavalry routed Lannoy's company of light horse; the Italians and the contingent from Gruyères, meanwhile, broke and fled—leaving their officers to be killed—without offering any real resistance to the advancing Imperial infantry.[52] As Cardona's infantry moved past the original French line, Enghien descended on it with the entire body of heavy cavalry under his command; the subsequent engagement took place on the reverse slope of the ridge, out of sight of the rest of the battlefield.[53]

On the first charge, Enghien's cavalry penetrated a corner of the Imperial formation, pushing through to the rear and losing some of the volunteers from Paris.[54] As Cardona's ranks closed again, the French cavalry turned and made a second charge under heavy arquebus fire; this was far more costly, and again failed to break the Imperial column.[55] Enghien, now joined by Dampierre's light cavalry, made a third charge, which again failed to achieve a decisive result; fewer than a hundred of the French gendarmes remained afterwards.[56] Enghien believed the battle to be lost—according to Montluc, he intended to stab himself, "which ancient Romans might do, but not good Christians"—when St. Julian, the Swiss commander, arrived from the center of the battlefield and reported that the Imperial forces there had been routed.[57]

The news of the landsknechts' defeat reached Cardona's troops at about the same time that it had reached Enghien; the Imperial column turned and retreated back towards its original position.[58] Enghien followed closely with the remainder of his cavalry; he was soon reinforced by a company of Italian mounted arquebusiers, which had been stationed at Racconigi and had started towards the battlefield after hearing the initial artillery exchange.[59] These arquebusiers, dismounting to fire and then remounting, were able to harass the Imperial column sufficiently to slow its retreat.[60] Meanwhile, the French and Swiss infantry of the center, having reached Ceresole, had turned about and returned to the battlefield; Montluc, who was with them, writes:

When we heard at Ceresole that M. d'Enghien wanted us, both the Swiss and we Gascons turned toward him—I never saw two battalions form up so quick—we got into rank again actually as we ran along, side by side. The enemy was going off at quick march, firing salvos of arquebuses, and keeping off our horse, when we saw them. And when they descried us only 400 paces away, and our cavalry making ready to charge, they threw down their pikes and surrendered to the horsemen. You might see fifteen or twenty of them round a man-at-arms, pressing about him and asking for quarter, for fear of us of the infantry, who were wanting to cut all their throats.[61]

Perhaps as many as half of the Imperial infantry were killed as they were attempting to surrender; the remainder, about 3,150 men, were taken prisoner.[62] A few, including the Baron of Seisneck, who had commanded the German infantry contingents, managed to escape.[63]

Aftermath[edit]

The casualties of the battle were unusually high, even by the standards of the time, and are estimated at 28 percent of the total number of troops engaged.[64] The smallest numbers given for the Imperial dead in contemporary accounts are between 5,000 and 6,000, although some French sources give figures as high as 12,000.[65] A large number of officers were killed, particularly among the landsknechts; many of those who survived were taken prisoner, including Ramón de Cardona, Carlo Gonzaga, and Eriprando Madruzzo.[66] The French casualties were smaller, but numbered at least 1,500 to 2,000 killed.[67] These included many of the officers of the Gascon and Gruyères infantry contingents, as well as a large portion of the gendarmerie that had followed Enghien.[68] The only French prisoner of note was Des Thermes, who had been carried along with Sanseverino's retreating Italians.[69]

Despite the collapse of the Imperial army, the battle proved to be of little strategic significance.[70] At the insistence of Francis I, the French army resumed the siege of Carignano, where Colonna held out for several weeks. Soon after the city's surrender, Enghien was forced to send twenty-three companies of Italian and Gascon infantry—and nearly half his heavy cavalry—to Picardy, which had been invaded by Charles V.[71] Left without a real army, Enghien was unable to capture Milan. D'Avalos, meanwhile, routed a fresh force of Italian infantry under Pietro Strozzi and the Count of Pitigliano at the Battle of Serravalle.[72] The end of the war saw a return to the status quo in northern Italy.

Historiography[edit]

A number of detailed contemporary accounts of the battle have survived. Among the French chronicles are the narratives of Martin Du Bellay and Blaise de Montluc, both of whom were present at the scene. The Sieur de Tavannes, who accompanied Enghien, also makes some mention of the events in his memoirs.[73] The most extensive account from the Imperial side is that of Paolo Giovio. Despite a number of inconsistencies with other accounts, it provides, according to historian Charles Oman, "valuable notes on points neglected by all the French narrators".[74]

The interest of modern military historians in the battle has centered primarily on the role of small arms and the resulting carnage among the infantry in the center.[75] The arrangement of pikemen and arquebusiers used was regarded as too costly, and was not tried again; in subsequent battles, arquebuses were used primarily for skirmishing and from the flanks of larger formations of pikemen.[76] Ceresole is also of interest as a demonstration of the continuing role of traditional heavy cavalry on the battlefield.[77] Despite the failure of Enghien's charges—the French, according to Bert Hall, held to their belief in "the effectiveness of unaided heavy cavalry to break disciplined formations"—a small body of gendarmes had been sufficient, in the center, to rout infantry columns that were already engaged with other infantry.[78] Beyond this tactical utility, another reason for cavalry's continued importance is evident from the final episode of the battle: the French gendarmes were the only troops who could reasonably be expected to accept an opponent's surrender, as the Swiss and French infantry had no inclination towards taking prisoners. The cavalry was, according to Hall, "almost intuitively expected to heed these entreaties without question".[79]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Arnold, Renaissance at War, 180; Blockmans, Emperor Charles V, 72–73; Oman, Art of War, 213.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 229.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 229. D'Avalos had captured Mondovì only a short time before.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 229. Oman, citing Du Bellay, describes the new fortifications as "five bastions, good curtains between them, and a deep ditch".

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 229–30.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 230. The Swiss, while trained as pikemen, had been raised by the Count of Gruyères from his own lands, rather than being traditional levies of the Swiss cantons; Oman cites Giovio's description of the men having been "raised from all regions of the Upper Rhone and the Lake of Geneva".

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 230. Oman notes that the garrison of Carignano included some of d'Avalos's best troops.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 230. Oman notes that Du Bellay, seemingly having some dislike for Montluc, avoids identifying the messenger in his chronicle, describing him as "un gentilhomme" without giving his name.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 230–231. The major source for Montluc's speech before Francis, and the ensuing debate, is Montluc's own autobiography; Oman writes that "his narrative cannot always be trusted, since he sees himself in the limelight at every crisis", but also notes that "it seems hardly credible that Montluc could have invented his whole graphic tale of the dispute at the council board, and his own impassioned plea for action". The requirement for Enghien's subordinates to agree to a battle is recorded by Du Bellay; Montluc does not mention it.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 231. A full list of names is given by Du Bellay and includes Dampierre, St. André, Vendôme, Rochefort, and Jarnac.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 231. The landsknechts in question were veteran troops, and had been specially equipped with corselets.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 186; Oman, Art of War, 231. Hall gives lower numbers than Oman, noting that they are estimates by Ferdinand Lot, and is the source for the specific proportion of arquebusiers in the Imperial army.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 231. Oman writes that d'Avalos related this view to Des Thermes, who had been captured by the Imperial troops, telling him that "after Pavia the Spanish officers had come to think little of the French gendarmerie, and believed that arquebusiers would always get the better of them, if properly covered".

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 231–232, 234. The blocking force probably consisted of the companies of French infantry that had arrived as reinforcements during the winter.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 232. The other route available to d'Avalos was a sweep south through Sommariva and Racconigi that would have exposed his flank to Enghien.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 232.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 186. Hall notes that Montluc, by his own account, told Enghien, "Sir sir, what more could you have desired of God Almighty [than] to find the enemy... in the open field, [with] neither hedge nor ditch to obstruct you?"

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 186; Oman, Art of War, 232–234. Oman notes that there are a variety of figures available for the strength of the French army; he gives "figures somewhat lower than Montluc's... and somewhat higher than Du Bellay's...". Hall gives the lower number for the infantry but the higher number for the heavy cavalry, in both cases from Lot, and notes that only around 500 of the heavy cavalry were actually gendarmes.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 232. Francis had sent some forty thousand écus, which was less than a month's worth of back pay.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 186; Oman, Art of War, 234. Hall explicitly attributes much of the uncoordinated action during the battle to the poor visibility along the line. Black also mentions the topography as a source of confusion (Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire,"43).

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 234. Oman suggests that this division seems to have been a theoretical one here.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 234. Oman notes that the full strength of the three companies should have been 650 troopers, rather than the smaller number actually present.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 234. The squadron under Boutières was also under-strength; it should have included a hundred troopers.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 234. St. Julian commanded six of the companies, and William Frülich the other seven.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 234. The heavy cavalry companies, commanded by Crusol, d'Accier, and Montravel, were also under-strength; the company of light horse, commanded by d'Ossun, was not, numbering about 150 men.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 232–235. Descroz was given the command because the Count of Gruyères had not yet arrived.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 235. The archers had been detached from the companies of heavy cavalry with which they normally operated.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 234–235. The ridge occupied by d'Avalos' troops shared the same peculiarity of having a high center separating the two wings from each other; d'Avalos found that a knoll in the center was the only place from which he could observe his entire position.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 231, 236.

- ^ a b c Oman, Art of War, 236.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 236. The Imperial heavy cavalry was positioned directly across from Enghien's cavalry.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 231, 236. Cardona's infantry consisted primarily of veterans from the African campaigns of Charles V.

- ^ a b Oman, Art of War, 235.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 235. Montluc's arquebusiers were drawn from the French and Italian infantry companies.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 235. Hall also mentions the skirmishing (Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187).

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 235. The Imperial cannon were divided among two batteries near a pair of farms in front of the Imperial center and right wing, while the French artillery, similarly split, was adjacent to the Swiss in the center and the Gruyères contingent on the left.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 186; Oman, Art of War, 235. Hall notes that the artillery "was kept well back... and officers on both sides took care not to expose unshielded infantry to its fire".

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 235–236.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 236. Oman, citing Du Bellay and Montluc, notes that Des Thermes, "thinking that he would have been better followed", drove deep into the enemy infantry before being unhorsed and taken prisoner.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 236. The source for Montluc's role in this incident is his own narrative.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 237. Oman, praising Madruzzo's tactical skill in effecting the division, quotes Du Bellay's description of the movement: "Seeing that the French had changed their plan, the Imperialists made a parallel change, and of their great battalion made two, one to fight the Swiss, the other the French, yet so close to each other that seen sideways they still looked one great mass." Hall calls the movement "an extremely difficult maneuver".

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 186–187. Hall notes that the later 16th-century system of arranging the infantry in square formations, with the arquebusiers drawn back into the center for protection, was probably not fully in place at Ceresole.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187–188; Oman, Art of War, 237.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 237. Hall gives a similar translation of Montluc's quote (but uses "a great slaughter" for "une grande tuerie"); he notes that it is unclear how Montluc "escaped the carnage he helped create" (Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187).

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 237. The Swiss waited until the French were "within twelve pike-lengths of their immediate adversaries" before starting from their position.

- ^ Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire", 43; Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 237–238.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 238. Oman notes that the actions of the Imperial cavalry are not mentioned in any French chronicle of the battle, but that Giovio records that they "disgraced themselves".

- ^ a b Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 238.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 238. Oman suggests that the contemporary casualty figure of 5,000 out of 7,000 is exaggerated, but notes that Giovio's list of casualties records that "practically all their captains were killed". Black merely notes the landsknechts' casualties as "more than 25 percent" (Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire", 43).

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 238. Baglioni's Florentines had been able to reform without incident, as they were not pursued by the French after the initial clash.

- ^ Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire", 43; Oman, Art of War, 238–239.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 239. Oman is critical of Enghien, who "lost all count of how the battle was progressing elsewhere... forgetting the duties of a commander-in-chief".

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 239. Oman compares the action here—"purely a matter of infantry versus cavalry"—to that of the Battle of Marignano.

- ^ Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire", 43; Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 239. Oman refers to Du Bellay and Montluc for accounts of the "slaughter in the second charge".

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 239–240. Oman notes that the third charge was apparently encouraged by Gaspard de Saulx, sieur de Tavannes; according to his own narrative, he told Enghien that "the cup must be drained to the dregs" ("'Monsieur, il faut boire cette calice'").

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 240. Oman is skeptical of Montluc's claim here, noting that "Montluc loves a tragic scene".

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 187; Oman, Art of War, 240.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 240. The arquebusiers had been detached to watch over the fords on the Maira River, some eight miles (13 km) away from the battle.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 240.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 240. Hall gives a similar translation of Montluc's account (Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 188).

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 188; Oman, Art of War, 240–241. Hall quotes Montluc: "more than half were slain, because we dispatched as many of those people as we could get our hands on". Oman notes that the prisoners included about 2,530 Germans and 630 Spaniards.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 240. Oman cites Giovio's account for this detail.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 217.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 241. Oman does not consider the higher French numbers to be probable.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 241. Oman notes that Giovio provides a full list of the slain captains, including "the heir of Fürstenberg, the Baron of Gunstein, two brothers Scaliger—Christopher and Brenno—Michael Preussinger, Jacob Figer, etc. etc.". Madruzzo was so heavily wounded as to be believed dead, but later recovered.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 241. Oman considers the loss of 500 men reported in some French chronicles to be "obviously understated".

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 241. Oman notes the deaths of five captains of the Gascon infantry—la Molle, Passin, Barberan, Moncault, and St. Geneviève—as well as all the captains of the Gruyères band, including Descroz and Charles du Dros, the governor of Mondovì. Among the heavy cavalry, the dead included two of Enghien's squires and a large number of volunteers, including d'Accier, D'Oyn, Montsallais, de Glaive, Rochechouart, Courville, and several dozen more.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 241.

- ^ Black, "Dynasty Forged by Fire", 43.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 242.

- ^ Knecht, Renaissance Warrior, 490; Oman, Art of War, 242–243. Oman puts the battle on June 2, while Knecht has it occur on June 4.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 243.

- ^ Oman, Art of War, 243. Oman notes that Giovio is "oddly wrong" in reversing the positions of the Swiss and the Gascons in the initial French line.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 188.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 188. Hall notes that the Imperial army, despite being better equipped with small arms, suffered more casualties than the French.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 188–190.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 188–189. Hall notes that Enghien "certainly had reason to expect better results than his charging troops achieved", as Cardona's infantry had been "in some disarray" when the French charges began.

- ^ Hall, Weapons and Warfare, 189–190. Hall writes of the episode—and the slaughter of much of the Imperial infantry despite their attempts to surrender—that "the new brutalities of sixteenth century warfare could hardly have been more cruelly exemplified".

References[edit]

- Arnold, Thomas F. (2006). The Renaissance at War. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 0060891955. OCLC 62341645.

- Black, Jeremy. "Dynasty Forged by Fire." MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 18, no. 3 (Spring 2006): 34–43. ISSN 1040-5992.

- Blockmans, Wim (2002). Emperor Charles V, 1500–1558. London: Arnold. ISBN 0340720387. OCLC 47901198.

- Hall, Bert S. (1997). Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801869945. OCLC 35521720.

- Knecht, Robert J. (1994). Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521417961. OCLC 782155832.

- Oman, Charles (1979). A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. New York: AMS Press. ISBN 0404145795. OCLC 4505705.

- Phillips, Charles; Axelrod, Alan, eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of Wars. Vol. G–R. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0816028511.

Further reading[edit]

- Courteault, P. Blaise de Monluc historien. Paris, 1908.

- Du Bellay, Martin, Sieur de Langey. Mémoires de Martin et Guillaume du Bellay. Edited by V. L. Bourrilly and F. Vindry. 4 volumes. Paris: Société de l'histoire de France, 1908–19.

- Giovio, Paolo. Pauli Iovii Opera. Volume 3, part 1, Historiarum sui temporis. Edited by D. Visconti. Rome: Libreria dello Stato, 1957.

- Lot, Ferdinand. Recherches sur les effectifs des armées françaises des guerres d'Italie aux guerres de religion, 1494–1562. Paris: École Pratique des Hautes Études, 1962.

- Monluc, Blaise de. Commentaires. Edited by P. Courteault. 3 volumes. Paris: 1911–25. Translated by Charles Cotton as The Commentaries of Messire Blaize de Montluc (London: A. Clark, 1674).

- Monluc, Blaise de. Military Memoirs: Blaise de Monluc, The Habsburg-Valois Wars, and the French Wars of Religion. Edited by Ian Roy. London: Longmans, 1971.

- Saulx, Gaspard de, Seigneur de Tavanes. Mémoires de très noble et très illustre Gaspard de Saulx, seigneur de Tavanes, Mareschal de France, admiral des mers de Levant, Gouverneur de Provence, conseiller du Roy, et capitaine de cent hommes d'armes. Château de Lugny: Fourny, 1653.