Ancient near eastern cosmology

Ancient near eastern (ANE) cosmology refers to the plurality of cosmological beliefs in the Ancient Near East (including Ancient Egypt, Babylonia, Sumer, Akkad, Ugarit, and ancient Israel and Judah) from the 4th millennium BC until the formation of the Macedonian Empire by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. This system of cosmology went on to have a profound influence on views in Egyptian cosmology, early Greek cosmology, Jewish cosmology, patristic cosmology, and Islamic cosmology. Until the modern era, variations of ancient near eastern cosmology survived with Hellenistic cosmology as the main competing system.

Key texts[edit]

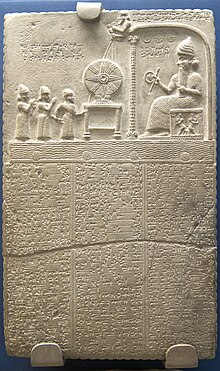

The Hebrew Bible (especially in the description found in the Genesis creation narrative) undergirds known beliefs about biblical cosmology in ancient Israel and Judah. The cosmology of the other civilizations has fragmentarily survived in the form of cuneiform literature primarily in the languages of Sumerian and Akkadian, which includes texts like the Enuma Elish and the MUL.APIN.[1] Another, albeit less abundant source of evidence, are pictorial/iconographic representations, notably including the Babylonian Map of the World. Evidentiary limitations include that the majority of surviving texts are administrative and economic in their nature, saying little about cosmology, and that formal statements about the structure of the cosmos only become known from the first millennium BC. Information about earlier periods is more dependent on gleaning information from creation myths and etiologies.[2]

Overview[edit]

Ancient near eastern cosmology can be divided into its cosmography, the physical structure and outline of the cosmos, and cosmogony, the creation myths that describe the origins of the cosmos in the texts and traditions of the ancient near eastern world.[3] Ancient near eastern civilizations held to a fairly uniform conception of cosmography. This cosmography remained remarkably stable in the context of the expansiveness and longevity of the ancient near east, but changes were also to occur.[4][5] There is evidence that Mesopotamian creation myths reached as far as Pre-Islamic Arabia.[6]

Cosmography[edit]

Widely held components of ancient near eastern cosmography included[1][7][8]:

- a Flat Earth (likely disk-shaped)

- a solid heaven (firmament), disk-shaped and floating above the Earth

- a primordial cosmic ocean: the creation of the firmament separates the cosmic ocean from the Earth and forms a body of heavenly, upper waters which acts as the source of rain

- above the upper waters lies the abode where the divine powers exist

- the lower waters which the Earth rests on

- the netherworld, the furthest region in the direction downwards, above which is the lower waters

Keyser, categorizing ancient near eastern cosmology as belonging to a larger and more cross-cultural set of cosmologies he describes as a "cradle cosmology," offers a longer list of shared features.[9] There are cosmographical notions attributed to, but unlikely to actually have been held by, Mesopotamian cosmologies (though they may have appeared in later or other cosmological thought). These include notions of the cosmos as a ziggurat reaching up to a peak, a cosmic mountain, and a dome-(or vault-) shaped firmament instead of a flat one.[10]

Cosmogony[edit]

Ancient near eastern cosmogony also included a number of common features that are present in most if not all creation myths from the ancient near east. These include the organization of the world from pre-existing, unformed elements, represented by a primordial body of water; the presence of a divine creator; an antagonist or primordial monster; a battle between the forces of good and evil; the separation of the elements; and the creation of mankind.[11] In earlier Sumerian accounts, supreme dominion over the cosmos was held by a trio of Gods in their respective domains: Anu ruled the remote heaven, Enki ruled the waters surrounding and below the Earth, and Enlil ruled the region between the great above and the great below. In later Babylonian accounts, the god Marduk alone ascends to the top rank of the pantheon and over all domains of the cosmos.[12]

Cosmographies[edit]

"The world"[edit]

A variety of terms or phrases existed that were used to refer to the cosmos as a whole, as an equivalent of "cosmos" or "universe". This included phrases like "heaven and earth" or "heaven and underworld". Terms like "all" or "totality" similarly connoted the entire universe. These motifs can be found in temple hymns or royal inscriptions which, inside of temples whose size was in some way symbolized to reach heaven in their height or the underworld in their depths or foundations.[13][14] Surviving evidence does not exactly specify the physical bounds of the cosmos or what lies beyond the region described in the texts.[15]

In Mesopotamian cosmology, heaven and Earth were themselves represented as having a tripartite structure: a Lower Heaven/Earth, a Middle Heaven/Earth, and an Upper Heaven/Earth. The Upper Earth was where humans existed. Middle Earth, corresponding to the Abzu (primeval underworldly ocean), was the residence of the god Enki. Lower Earth, the Mesopotamian underworld, was where the 600 Anunnaki gods lived, associated with the land of the dead ruled by Nergal. As for the heavens: the highest level was populated by 300 Igigi (great gods), the middle heaven belonged to the Igigi and also contained Marduk's throne, and the lower heaven was where the stars and constellations were inscribed into. Poetic speculation existed over whether the different levels of heaven were composed of different stones. In total, the extent of the Babylonian universe therefore corresponded to a total of six layers spanning across heaven and Earth.[16][17][18] Notions of the plurality of the heavens and Earth go back, at the latest, to the 2nd millennium BC and may be elaborations on simpler cosmographies.[19] One text (KAR 307) that post-dates the Enuma Elish describes the cosmos as follows, with each of the three floors of heaven being made of a different type of stone[20][21]:

30 “The Upper Heavens are Luludānītu stone. They belong to Anu. He (i.e. Marduk) settled the 300 Igigū (gods) inside.

31 The Middle Heavens are Saggilmud stone. They belong to the Igīgū (gods). Bēl (i.e. Marduk) sat on the high throne within,

32 the lapis lazuli sanctuary. And made a lamp? of electrum shine inside (it).

33 The Lower Heavens are jasper. They belong to the stars. He drew the constellations of the gods on them.

34 In the … …. of the Upper Earth, he lay down the spirits of mankind.

35 [In the …] of the Middle earth, he settled Ea, his father.

36 […..] . He did not let the rebellionbe forgotten.

37 [In the … of the Lowe]r earth, he shut inside 600 Anunnaki.

38 […….] … […. in]side jasper.

Another text (AO 8196) offers a slightly different arrangement, with the Igigi in the upper heaven instead of the middle heaven, and with Bel placed in the middle heaven. Both agree on the placement of the stars in the lower heaven. Exodus 24:9–10 identifies the floor of heaven as being like sapphire, which may correspond to the blue lapis lazuli floor in KAR 307, chosen potentially for its correspondence to the visible color of the sky.[22] One hypothesis holds that the belief that the firmament is made of stone (or a metal, such as iron in Egyptian texts[23]) arises from the observation that meteorites, which are composed of this substance, fall from the firmament.[24] Mythical bonds, akin to ropes or cables, played the role of cohesively holding the entire world and all its layers of heaven and Earth together. These are sometimes called the "bonds of heaven and earth". They can be referred to with terminology like durmāhu (typically referring to a strong rope made of reeds), markaṣu (referring to a rope or cable, of a boat, for example), or ṣerretu (lead-rope passed through an animals nose). A deity can hold these ropes as a symbol of their authority, such as the goddess Ishtar "who holds the connecting link of all heaven and earth (or netherworld)". This motif extended to descriptions of great cities like Babylon which was called the "bond of [all] the lands," or Nippur which was "bond of heaven and earth," and some temples as well.[25]

The idea of a center to the cosmos also played a role in elevating where that center was placed and in reflecting beliefs of the finite and closed nature of the cosmos. Babylon was described as the center of the Babylonian cosmos. In parallel, Jerusalem became "the navel of the earth" (Ezekiel 38:12).[26] The finite nature of the cosmos was also suggested to the ancients by the periodic and regular movements of the heavenly bodies in the visible vicinity of the Earth.[27][28]

Firmament[edit]

The firmament was believed to be a solid boundary above the Earth, separating it from the upper or celestial waters. In the Book of Genesis, it is called the raqia.[29][30] In ancient Egyptian texts, and from texts across the near east generally,[31] it was described that the firmament had special doors or gateways on the eastern and western horizons to allow for the passage of heavenly bodies during their daily journeys. In Egyptian texts particularly, these gates also served as conduits between the earthly and heavenly realms for which righteous people could ascend. The gateways could be blocked by gates to prevent entry by the deceased as well. As such, funerary texts included prayers enlisting the help of the gods to enable the safe ascent of the dead.[32] Ascent to the celestial realm could also be done by a celestial ladder made by the gods.[33] Multiple stories exist in Mesopotamian texts whereby certain figures ascend to the celestial realm and are given the secrets of the gods.[34]

Four different Egyptian models are known for the nature of the firmament and/or the heavenly realm. One was that of a bird: the firmament above represented the underside of a flying falcon, with the sun and moon representing its eyes, and its flapping causes the wind that humans experience.[35] The second was a cow, known from a text known as the Book of the Heavenly Cow. The cosmos is a giant celestial cow represented by the goddess Nut or Hathor. The cow consumed the sun in the evening and rebirthed it in the next morning.[36] The third is a celestial woman, also represented by Nut. The heavenly bodies would travel across her body from east to west. The midriff of Nut was supported by Shu (the air god) and Geb (the earth god) lied out stretched between the arms and feet of Nut. Nut consumes the celestial bodies from the west and gives birth to them again in the following morning. The stars are inscribed across the belly of Nut and one needs to identify with one of them, or a constellation, in order to join them after death.[37] The fourth model was a flat (or slightly convex) celestial plane which in different texts is said to be supported in various ways: by pillars, or staves, scepters, or mountains at the extreme ends of the Earth. The four supports give rise to the motif of the "four corners of the world".[38]

Some texts describe seven heavens and seven earths, but within the Mesopotamian context, this is likely to refer to a totality of the cosmos with some sort of magical or numerological significance, as opposed to a description of the structural number of heavens and Earth.[39] Israelite texts do not mention the notion of seven heavens or earths.[40]

Earth[edit]

The ancient near eastern Earth was a single-continent flat disc.[7][8] A common honorific that many kings and rulers ascribed to themselves was that they were the rulers of the four quarters (or corners) of the Earth. For example, Hammurabi (ca. 1810–1750 BC) received the title of "King of Sumer and Akkad, King of the Four Quarters of the World". Monarchs of the Assyrian empire like Ashurbanipal also took on this title. (Although the title implies a square or rectangular shape, in this case it is taken to refer to the four quadrants of a circle which is joined at the worlds center.) Likewise, the 'four corners' motif would also appear in some biblical texts, like Isaiah 11:12.[41]

The cosmography of the Earth is pictorially elucidated by the Babylonian Map of the World. Here, the city Babylon is near the Earth's center and it is on the Euphrates river. Other kingdoms and cities surround it. The world is flat and circular and it is surrounded by a bitter salt-water ocean. The north is covered by an enormous mountain range, akin to a wall. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh journeys past this mountain range to an area that can only be accessed by gods and other heroes.[42] Furthermore, the enter earth is represented as a continent surrounded by an Ocean (called marratu, or "salt-sea")[43] akin to Oceanus described in the poetry of Homer and Hesiod, as well as the statement in the Bilingual Creation of the World by Marduk that Marduk created the first dry land surrounded by a cosmic sea.[44] The furthest and most remote parts of the earth were inhabited by fantastic creatures.[45]

Cosmic mountain (Mashu)[edit]

Stories emerged that described a great hero following in the path or daily course of the sun god. These stories have been attributed to Gilgamesh, Odysseus, the Argonauts, Heracles and, in later periods, Alexander the Great.[46][47] In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh reaches what are two cosmological mountains or is a twin-peaked cosmological mountain, called Mashu acting as the sun-gate, the location from where the sun rises and sets. In some texts, this structure is referred to as the mountain of sunrise and sunset. According to iconographic and literary evidence, Mashu was thought to be located at or extend to both the westernmost and easternmost points of the earth, where the sun could rise and set respectively. As such, the model may be called a bi-polar model of diurnal solar movement. The gate for the suns rising and setting was also located at Mashu.[48] Some accounts have Mashu as a tree growing at the center of the earth with roots descending into the underworld and a peak reaching to heaven.[49]

Heavenly bodies[edit]

Mesopotamian cosmology would differ from the practice of astronomy in terms of terminology: for astronomers, the word "firmament" was not used but instead "sky" to describe the domain in which the heavenly affairs were visible. The stars were located on the firmament, arranged by Marduk himself into constellations to depict the images of the gods. The fixation of these stars also organized the year into 12 months. Each month was marked by the rising of three stars along specified paths. The moon and zenith were also created. Creation and characterization of other phenomena, including lunar phases and an overall lunar scheme, precise paths and the rising and setting of the stars, stations of the planets, and more, occurred.[50][51][52] An alternative account of the creation of the heavenly bodies is offered in the Babyloniaca of Berossus, where Bel (Marduk) creates stars, sun, moon, and the five (known) planets; the planets here do not help guide the calendar (a lack of concern for the planets also shared in the Book of the Courses of the Heavenly Luminaries, a subsection of 1 Enoch).[53] Concern for the establishment of the calendar by the creation of heavenly bodies as visible signs is shared in at least seven other Mesopotamian texts. A Sumerian inscription of Kudur-Mabuk, for example, reads "The reliable god, who interchanges day and night, who establishes the month, and keeps the year intact." Another example is to be found in the Exaltation of Inanna.[54]

The word "star" (kakkabu) was inclusive to all celestial bodies, stars, constellations, and planets. A more specific concept for planets existed, however, to distinguish them from the stars: unlike the stars fixed into their location, the planets were observed to move. By the 3rd millennium BC, the planet Venus was identified as the astral form of the goddess Inanna (or Ishtar), and motifs such as the morning and evening star were applied to her. Jupiter became Marduk (hence the name "Marduk Star", also called Nibiru), Mercury was the "jumping one" (in reference to its comparatively fast motion and low visibility) associated with the gods Ninurta and Nabu, and Mars was the god of pestilence Nergal and thought to portend evil and death. Saturn was also sinister. The most obvious characteristic of the stars were their luminosity and their study for the purposes of divination, solving calendrical calculations, and predictions of the appearances of planets, led to the discovery of their periodic motion. From 600 BC onwards, the study of the relative periodicity between their bodies began to be studied.[55]

Daily course of the sun[edit]

When the sun rose in the day, it passes over the earth. It falls beneath the earth in the night and comes to a resting point. This resting point is sometimes localized to a designated structure, such as the chamber within a house in the Old Babylonian Prayer to the Gods of the Night. To complete the cycle, the sun comes out in the next morning. Likewise, the moon was thought to rest in the same facility when it was not visible.[56] These images result from anthropomorphizing the sun and other astral bodies, who had also been conceived as gods.[57] For the sun to exit beneath the earth, it had to cross the solid firmament: this was thought possible by the existence of opening ways or corridors in the firmament (variously illustrated as doors, windows or gates) that could temporarily open and close to allow astral bodies to pass across them. The firmament was conceived as a gateway, with the entry/exit point as the gates; other opening and closing mechanisms were also imagined in the firmament like bolts, bars, latches, and keys.[58] During the suns movement beneath the earth, into the netherworld, the sun would cease to flare; this way the netherworld remained dark. But when it rose, it would flare up and again emit light.[59] One inconsistency in this image was to understand how, if the sun rested during the night, could it traverse the same distance beneath the earth as it did during the day such that it periodically rose from the east. Different solutions existed in different cultures and texts. One of these in some ancient near eastern texts was to drop the idea of the suns rest and instead imagine it as unceasing in its course.[60]

Overall, the sungods activities in night according to Sumerian and Akkadian texts proceeds as follows: (1) The western door of heaven opens (2) The sun passes through the door into the interior of heaven (3) Light falls below the western horizon (4) The sun engages in certain activities in the netherworld like judging the dead (5) The sun enters a house, called the White House (6) The sungod eats the evening meal (7) The sungod sleeps in the chamber agrun (8) The sun emerges from the chamber (9) The eastern door opens and the sun passes through as it rises.[61]

Upper waters[edit]

Above the firmament was a large, cosmic body of water which may be referred to as the cosmic ocean or celestial waters. In the Tablet of Shamash, the throne of the sun god Shamash is depicted as resting above the cosmic ocean. The waters are above the solid firmament that covers the sky.[62] Mesopotamian cosmology held that the upper waters were the waters of Tiamat, contained by Tiamat's stretched out skin.[52] Egyptian texts depict the sun god sailing across these upper waters. Some also convey that this body of water is the heavenly equivalent of the Nile River.[63]

Lower waters[edit]

Both Babylonian and Israelite texts describe one of the divisions of the cosmos as the underworldly ocean. In Babylonian texts, this is coincided with the region/god Abzu.[64] In Sumerian mythology, this realm was created by Enki. It was also where Enki lived and ruled over. Due to the connection with Enki, the lower waters were associated with wisdom and incantational secret knowledge.[65] In Egyptian mythology, the personification of this subterranean body of water was instead Nu. The notion of a cosmic body of water below the Earth was inferred from the realization that much water used for irrigation came from under the ground, from springs, and that springs were not limited to any one part of the world. Therefore, a cosmic body of water acting as a common source for the water coming out of all these springs was conceived.[27]

Underworld[edit]

The underworld, or the netherworld, was the lowest of all the regions, below Abzu. It was geographically in parallel with the plane of human existence, but was so low that both demons and gods could not descend to it. It was, however, inhabited by beings such as ghosts, demons, and gods. The land was depicted as dark and distant: this is because it was the opposite of the human world and so did not have light, water, fields, and so forth.[66] According to KAR 307, line 37, Bel cast 600 Annunaki into the underworld. They were locked away there, unable to escape, analogous to the enemies of Zeus who were confined to the underworld (Tartarus) after their rebellion during the Titanomachy. During and after the Kassite period, Annunaki were largely depicted as underworld deities; a hymn to Nergal praises him as the "Controller of the underworld, Supervisor of the 600".[67]

Cosmogonies[edit]

Overview[edit]

The creation myths conceive and explain the origins of the two fundamental parts of the cosmos, the heaven and the Earth, as resulting from a separation from what was first one single mass. In one myth known as Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld, in the introduction says that heaven is carried off from the earth by the sky god Anu and becomes the possession of the wind god Enlil. Nammu is the original mother that gave birth to the great undifferentiated mass that would eventually become the heaven and earth. The heaven and earth could represent the father (heaven) and earth (mother). The sky has generative power, and the rain is a representation of semen that falls upon the Earth allowing it to give rise/birth to vegetation. An alternative cosmogony represented the heaven and earth as gods that originated as the distinct offspring of other gods and not as originating from a separation of an earlier unseparated mass. An example of this is in the great Akkadian creation poem, the Enuma Elish.[68]

Origins of the gods[edit]

All gods descend from an original male–female pair known as Enki and Ninki, whose names literally mean "Lord and Lady Earth". The primordial Enki is not to be confused with the god of wisdom, who is also named Enki. Sources also differentiate between the inanimate matter from which the universe was made and the soul-like substance permeating living creates like gods and humans. In the Akkadian tradition, the primordial universe is alive and animate, made of Abzu (male deity of the fresh waters) and Tiamat (female sea goddess). The waters mingle to create the next generations of deities.[69]

Separating heaven and earth[edit]

The idea that heaven and Earth were originally joined and then separated is widespread in widespread in ancient near eastern cosmology, going back at least to the 3rd millennium BC, and appears not only in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, but also Phoenician, Egyptian, and likely early Greek cosmology too.[70] One recovered Hittite text states that there was a time when they "severed the heaven from the earth with a cleaver", and an Egyptian text refers to "when the sky was separated from the earth" (Pyramid Text 1208c).[23] There are two strands of Mesopotamian creation myths regarding the original separation of the heavens and earth. The first, older one, is evinced from texts in the Sumerian language from the 3rd millennium BC and the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. In these sources, the heavens and Earth are separated from an original solid mass. In the younger tradition known from texts in the Akkadian language, such as the Enuma Elish, the separation occurs from an original water mass. The former usually has the leading gods of the Sumerian pantheon, the King of Heaven Anu and the King of Earth Enlil, separating the mass over a time-frame of "long days and nights", similar to the timeframe given in the Genesis creation narrative (six days and nights). Genesis also parallels another version of these stories where a primordial darkness pervades prior to the creation of light. The Sumerian texts do not mention the creation of the cosmic waters but it may be surmised that water was one of the primordial elements.[69]

Stretching out the heavens[edit]

The idiom of the heavens and earth being stretched out plays both a cultic and cosmic role in the Hebrew Bible where it appears repeatedly in the Book of Isaiah (40:22; 42:5; 44:24; 45:12; 48:13; 51:13, 16), with related expressions in the Book of Job (26:7) and the Psalms (104:2). One example reads "The one who stretched out the heavens like a curtain / And who spread them out like a tent to dwell in" (Is 40:22). The idiom is used in these texts to identify the creative element of Yahweh's activities and the expansion of the heavens signifies its vastness, acting as Yahweh's celestial shrine. In Psalmic tradition, the "stretching" of the heavens is analogous to the stretching out of a tent. The Hebrew verb for the "stretching" of the heavens is also the regular verb for "pitching" a tent. The heavens, in other words, may be depicted as a cosmic tent (a motif found in many ancient cultures[71][72]). This finds architectural analogy in descriptions of the tabernacle, which is itself a heavenly archetype, over which a tent is supposed to have been spread.[73] The phrase is frequently followed by an expression that God sits enthroned above and ruling the world, paralleling descriptions of God being seated in the Holy of Holies of the Tabernacle where he is stated to exercise rule over Israel.[74] Biblical references to stretching the heavens typically occur in conjunction with statements that God made or laid the foundations of the earth.[75]

Similar expressions may be found elsewhere in the ancient near east. A text from the 2nd millennium BC, the Ludlul Bēl Nēmeqi, says "Wherever the earth is laid, and the heavens are stretched out", though the text does not identify the creator of the cosmos.[76] The Enuma Elish also describes the phenomena, in IV.137–140[77]:

137 He split her into two like a dried fish:

138 One half of her he set up and stretched out as the heavens.

139 He stretched the skin and appointed a watch.

140 With the instruction not to let her waters escape.

In this text, Marduk takes the body of Tiamat, who he has killed, and stretches out Tiamat's skin to create the firmamental heavens which, in turn, comes to play the role of preventing the cosmic waters above the firmament from escaping and being unleashed onto the earth. Whereas the Masoretic Text of the Hebrew Bible states that Yahweh stretched heaven like a curtain in Psalm 104:2, the equivalent passage in the Septuagint instead uses the analogy of stretching out like "skin", which could represent a relic of Babylonian cosmology from the Enuma Elish. Nevertheless, the Hebrew Bible never identifies the material out of which the firmament was stretched.[78] Numerous theories about what the firmament was made of sprung up across ancient cultures.[79]

Enuma Elish[edit]

Context and summary[edit]

The Enuma Elish is the most famous Mesopotamian creation story and was widely known in among learned circles across Mesopotamia, and it went on to influence both art and ritual.[80] The story was, in many ways, an original work, and as such is not a general representative of ancient near eastern or even Babylonian cosmology as a whole, and its survival as the most complete creation account appears to be a product of it having been composed in the milieu of Babylonian literature that happened to survive and get discovered in the present day.[81] The story is preserved foremost in seven clay tablets discovered from the Library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh. The creation myth seeks to describes how the god Marduk created the world from the body of the sea monster Tiamat after defeating her in battle, after which Marduk ascends to the top of the heavenly pantheon.[82][83] The creation account in this source is the earliest complete Mesopotamian creation account. Earlier cosmogonies must be reconstructed from disparate sources.[84]

Synopsis[edit]

The following is a synopsis of the account. The primordial universe is alive and animate, made of Abzu (male deity of the fresh waters) and Tiamat (female sea goddess). The waters mingle to create the next generations of deities. A series of controversies lead to the death of both Abzu and Tiamat with the emergence of Marduk at the top of the heavenly pantheon. Marduk creates the cosmos, humanity, and sets up a divine capital at BabylonBut the noisiness of the younger gods leads Abzu to try to kill them: he is stopped and in turn himself killed by the god Ea, who is the Akkadian equivalent of the Sumerian god Enki. This eventually results in a battle between Tiamat and the son of Ea, Marduk. Marduk kills Tiamat and fashions the cosmos, including the heavens and Earth, from Tiamat's corpse. Tiamat's breasts are used to make the mountains and Tiamat's eyes are used to open the sources of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Parts of the watery body were used to create parts of the world including its wind, rain, mist, and rivers. Marduk forms the heavenly bodies including the sun, moon, and stars to produce periodic astral activity that is the basis for the calendar, before finally setting up the cosmic capital at Babylon. Marduk attains universal kingship and the Tablet of Destinies. Tiamat's helper Kingu is also slain and his life force is used to animate the first human beings.[69][85]

Continuity with earlier cosmogonies[edit]

The Enuma Elish shares continuity with earlier traditions like in the Myth of Anzû. In both, a dragon (Anzu or Tiamat) steals the Tablet of Destinies from Enlil, the chief god and in response, the chief god looks for someone to slay the dragon. Then, in both stories, a champion among the gods is chosen to fight the dragon (Ninurta or Marduk) after two or three others before them reject the offer to fight. The champion wins, after which he is acclaimed and given many names. The Enuma Elish may have also drawn from the myth of the Ninurta and the dragon Kur. The dragon is formerly responsible for holding up the primordial waters. Upon being killed, the waters begin to rise; this problem is solved by Ninurta heaping stones upon them until the waters are held back. Another myth involves Enlil fighting against the sea monster Labbu. As in the Enuma Elish, Enlil only fights when another god fails to. Both Enlil in his fight against Labbu and Marduk in his fight against Tiamat use the wind and storm in order to defeat their enemy. Traditions of the combat between Marduk and Tiamat may also be rooted in stories of the battle between the thunderstorm god Baal and the sea god Yam. One of the most significant differences between the Enuma Elish and earlier creation myths is in its exaltation of Marduk as the highest god. In prior myths, Ea was the chief god and creator of mankind.[82]

Genesis creation narrative[edit]

The Genesis creation narrative, composed sometime between the 7th and 6th centuries BC and spanning Gen 1:1–2:3, corresponds to a one-week (or seven-day) period involving the creation of the light (day 1); the sky (day 2); the earth, seas, and vegetation (day 3); the sun and moon (day 4); animals of the air and sea (day 5); and land animals and humans (day 6). God then rests from his work on the seventh day of creation, the Sabbath.[86]

Babyloniaca of Berossus[edit]

The first book of the Babyloniaca of the Babylonian priest Berossus, composed in the third century BC, offers a variant (or, perhaps, an interpretation) of the cosmogony of the Enuma Elish. This work is not extant but survives in later quotations and abridgements. Berossus' account begins with a primeval ocean. Unlike in the Enuma Elish, where sea monsters are generated for combat with other gods, in Berossus' account, they emerge by spontaneous generation and are described in a different manner to the 11 monsters of the Enuma Elish, as it expands beyond the purely mythical creatures of that account in a potential case of influence from Greek zoology.[87] Surviving fragments of Berossus now record two different versions of the cosmic battle event that is followed by an act of creation. Both variants may both go back to Berossus. According to Beaulieu, the first one reads[88]:

(BNJ 680 1b: 7) When everything was arranged in this way, Belus rose up and split the woman in two. Of one half of her he made earth, of the other half sky; and he destroyed all creatures in her. He says that this was an allegorical discourse on nature, for when everything was moist and creatures came into being in it, this god took off his own head and the other gods mixed the blood that flowed out with earth and formed men. For this reason they are intelligent and share in divine wisdom.

And the second one[88]:

(BNJ 680 1b: 8) Belus, whom they translate as Zeus, cut the darkness in half and separated earth and sky from each other and ordered the universe. The creatures could not endure the power of the light and were destroyed. When Belus saw the land empty and barren, he ordered one of the gods to cut off his own head and to mix the blood that flowed out with earth and to form men and wild animals that were capable of enduring the air.

The conclusion of the account states that Belus then created the stars, sun, moon, and five planets. Both variant accounts largely agree with the Enuma Elish but also contain a number of differences, such as the statement about allegorical exegesis, the self-decapitation of Belus in order to create humans, and the statement that it is the divine blood which has made humans intelligent. Some debate has ensued about which elements of these may or may not go back to the original account of Berossus.[89]

Other cosmogonies[edit]

Additional minor texts also present varying cosmogonical details. The Bilingual Creation of the World by Marduk describes the construction of Earth as a raft over the cosmic waters by Marduk. An Akkadian text called The Worm describes a series of creation events: first Heaven creates Earth, Earth creates the Rivers, and eventually, the worm is created at the end of the series and it goes to live in the root of the tooth that is removed during surgery.[69]

Influence[edit]

Survival[edit]

Copies from the Sippar Library indicate the Enuma Elish was copied into Seleucid times. One Hellenistic-era Babylonian priest, Berossus, wrote a Greek text about Mesopotamian traditions called the Babyloniaca (History of Babylon). The text survives mainly in fragments, especially by quotations in Eusebius in the fourth-century. The first book contains an account of Babylonian cosmology and, though concise, contains a number of echoes of the Enuma Elish. The creation account of Berossus is attributed to the divine messenger Oannes in the period after the global flood and is derivative of the Enuma Elish but also has significant variants to it.[90][91] Babylonian cosmology also received treatments by the lost works of Alexander Polyhistor and Abydenus. The last known evidence for reception of the Enuma Elish is in the writings of Damascius (462–538), who had a well-informed source.[91] As such, some learned circles in late antiquity continued to know the Enuma Elish.[92] Echoes of Mesopotamian cosmology continue into the 11th century.[93]

Zoroastrian cosmology[edit]

The earliest Zoroastrian sources describe a tripartite sky, with an upper heaven where the sun exists, a middle heaven where the moon exists, and a lower heaven where the stars exist and are fixed. Significant work has been done on comparing this cosmography to ones present in Mesopotamian, Greek, and Indian parallels. In light of evidence which has emerged in recent decades, the present view is that this idea entered into Zoroastrian thought through Mesopotamian channels of influence.[94][95] Another influence is that the name that one of the planets took on in Middle Persian literature, Kēwān (for Saturn), was derived from the Akkadian language.[96]

Early Greek cosmology[edit]

Early Greek cosmology was closely related to the broader domain of ancient near eastern cosmology, as is reflected by works from the 8th century BC such as the Theogony of Hesiod and the works of Homer. The flat Earth was surrounded by an ocean with a flat and solid firmament above supported by pillars. This basic conception would be modified by the advent of the observation and studies by the Ionian School of philosophy at the city of Miletus from the 6th to 4th centuries BC. Later on, a more systematic and entirely different Hellenistic system of cosmology would appear in the works of authors like Aristotle and the astronomer Ptolemy.[97]

Jewish cosmology[edit]

The primary influence that ancient near eastern cosmology continued to have on subsequent civilizations and traditions was by the form it had taken on in the Genesis creation narrative. For example, rabbinic cosmology as described by the authors of rabbinic literature borrowed its fundamental grasp of the cosmos from ancient near eastern cosmology.[98]

Christian cosmology[edit]

Christian texts were familiar with ancient near eastern cosmology insofar as it had shaped the Genesis creation narrative. A genre of literature emerged among Jews and Christians dedicated to the composition of texts commenting precisely on this narrative to understand the cosmos and its origins: these works are called Hexaemeron.[99] The first extant example is the De opificio mundi ("On the Creation of the World") by the first-century Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria. Philo preferred an allegorical form of exegesis, in line with that of the School of Alexandria, and so was partial to a Hellenistic cosmology as opposed to an ancient near eastern one. In the late fourth century, the Hexaemeral genre was revived and popularized by the Hexaemeron of Basil of Caesarea, who composed his Hexaemeron in 378, which subsequently inspired numerous works including among Basil's own contemporaries. Basil was much more literal in his interpretation than Philo, closer instead to the exegesis of the School of Antioch. Christian authors would heavily dispute the correct degree of literal or allegorical exegesis in future writings. Among Syrian authors, Jacob of Serugh was the first to produce his own Hexaemeron in the early sixth century, and he was followed later by Jacob of Edessa's Hexaemeron in the first years of the eighth century. The most literal approach was that of the Christian Topography by Cosmas Indicopleustes, which presented a cosmography very similar to the traditional Mesopotamian one, but in turn, John Philoponus wrote a harsh rebuttal to Cosmas in his own De opificio mundi.[100][101]

Cosmographies were described in works other than those of the Hexaemeral genre. For example, in the genre of novels, the Alexander Romance would portray a mythologized picture of the journeys and conquests of Alexander the Great, ultimately inspired by the Epic of Gilgamesh. The influence is evident in the texts cosmography, as Alexander reaches an outer ocean circumscribing the Earth which cannot be passed.[102] Both in the Alexander Romance, and in later texts like the Syriac Alexander Legend (Neshana), Alexander journeys to the ends of the Earth which is surrounded by an ocean. Unlike in the story of Gilgamesh, however, this ocean is an unpassable boundary that marks the extent to which Alexander can go.[103] The Neshana also aligns with a Mesopotamian cosmography in its description of the path of the sun: as the sun sets in the west, it passes through a gateway in the firmament, cycles to the other side of the earth, and rises in the east in its passage through another celestial gateway. Alexander, like Gilgamesh, follows the path of the sun during his journey. These elements of Alexander's journey are also described as part of the journey of Dhu al-Qarnayn in the Quran.[104] Gilgamesh's journey takes him to a great cosmic mountain known as Mashu; likewise, Alexander reaches a cosmic mountain known as Musas.[105] The cosmography depicted in this text greatly resembles that outlined by the Babylonian Map of the World.[106]

Islamic cosmology[edit]

The Quran conceives of the primary elements of the ancient near eastern cosmography, such as the division of the cosmos into the heavens and the Earth, a solid firmament, upper waters, a flat Earth, and seven heavens.[107] As with rabbinic cosmology, however, these elements were not directly transmitted from ancient near eastern civilization. Instead, work in the field of Quranic studies has identified the primary historical context for the reception of these ideas to have been in the Christian and Jewish cosmologies of late antiquity.[108] This conception of the cosmos was carried on into the traditionalist cosmologies that were held in the caliphate, though with a few nuances that appear to have emerged.[109]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Lambert 2016, p. 108–110.

- ^ George 2016.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. xii–xiii.

- ^ Hezser 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Al-Jallad 2015.

- ^ a b Panaino 2019, p. 16–24.

- ^ a b Seely 1997.

- ^ Keyser 2020, p. 18–19.

- ^ Lambert 2016, p. 120.

- ^ Tamtik 2007, p. 65–66.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 39–40.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 306.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. xiii.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. 9–19.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 311–313.

- ^ Lambert 2016, p. 118–119.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 43–44.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. 3–5.

- ^ Panaino 2019, p. 93–96.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. 8–9, 13–14.

- ^ a b Seely 1991, p. 233.

- ^ Johnson 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 44–45.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 45.

- ^ a b Lambert 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Grosu 2019, p. 53–54.

- ^ Seely 1991.

- ^ Seely 1992.

- ^ Kulik 2019, p. 243.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 19, 33–34.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 43–44.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 6–7.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 7–8.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 8–10.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 10–16.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 54–55.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 17–18.

- ^ Hannam 2023, p. 19.

- ^ Horowitz 1988.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Keyser 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Bilic 2022.

- ^ Van der Sluijs 2020.

- ^ Bilic 2022, p. 9–11.

- ^ Keyser 2020, p. 10.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 180–192.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 48–50.

- ^ a b Rochberg 2020, p. 313.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 172.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 172–180.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 315–317.

- ^ Heimpel 1986, p. 128–132.

- ^ Heimpel 1986, p. 147–148.

- ^ Heimpel 1986, p. 132–140.

- ^ Heimpel 1986, p. 142.

- ^ Heimpel 1986, p. 147.

- ^ Heimpel 1986, p. 150.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 36–37.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 10–13.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 53–54.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 314.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 314–315.

- ^ Horowitz 1998, p. 18–19.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 306–307.

- ^ a b c d Horowitz 2015.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 169–171.

- ^ Habel 1972, p. 428.

- ^ Klein 2006.

- ^ Habel 1972.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 38–39.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 39–40.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 42.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 43.

- ^ Kim 2020, p. 44–45.

- ^ Rappenglück 2004.

- ^ Talon 2001, p. 268–269.

- ^ Lambert 2013, p. 464–465.

- ^ a b Tamtik 2007.

- ^ Rochberg 2008, p. 41–42.

- ^ George 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Rochberg 2020, p. 307–308.

- ^ Sarna 1966, p. 1–2.

- ^ Beaulieu 2021, p. 152–156.

- ^ a b Beaulieu 2021, p. 156.

- ^ Beaulieu 2021, p. 157–161.

- ^ Beaulieu 2021, p. 152.

- ^ a b Talon 2001, p. 270–274.

- ^ Decharneux 2023, p. 116n381.

- ^ Talon 2001, p. 275–278.

- ^ Panaino 1995, p. 218–221.

- ^ Panaino 2019, p. 97–98.

- ^ Panaino 2019, p. 142.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 70–71.

- ^ Simon-Shoshan 2008, p. 69, 72.

- ^ Robbins 1912.

- ^ Kochańczyk-Bonińska 2016.

- ^ Tumara 2024.

- ^ Debié 2024, Chapter 3 § Une cosmographie mésopotamienne.

- ^ Debié 2024, Chapter 3 § La mer morte ou fétide : l’océan qui entoure le monde.

- ^ Debié 2024, Chapter 3 § Le chemin du soleil et les portes du ciel.

- ^ Debié 2024, Chapter 3 § Le mont Mashu.

- ^ Debié 2024, Chapter 3 § La carte babylonienne du monde et la carte d’Alexandre.

- ^ Tabatabaʾi & Mirsadri 2016.

- ^ Decharneux 2023.

- ^ Anchassi 2022, p. 854–861.

Sources[edit]

- Al-Jallad, Ahmad (2015). "Echoes of the Baal Cycle in a Safaito-Hismaic Inscription". Journal of Near Eastern Religions. 15: 5–19.

- Anchassi, Omar (2022). "Against Ptolemy? Cosmography in Early Kalām". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 142 (4): 851–881.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2021). "Berossus and the Creation Story". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 8 (1–2): 147–170. doi:10.1515/janeh-2020-0012.

- Bilic, Tomislav (2022). "Following in the Footsteps of the Sun: Gilgameš, Odysseus and Solar Movement". Annali Sezione Orientale. 82 (1–2): 3–37.

- Debié, Muriel (2024). Alexandre le Grand en syriaque. Les Belles Lettres.

- Decharneux, Julien (2023). Creation and Contemplation The Cosmology of the Qur'ān and Its Late Antique Background. De Gruyter.

- George, Andrew (2016). Die Kosmogonie des alten Mesopotamien (PDF).

- Grosu, Emanuel (2019). "The Heliocentrism of the Ancient: Between Geometry and Physics". Hermeneia. 23: 53–61.

- Habel, Norman C. (1972). ""He Who Stretches Out The Heavens"". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 34 (4): 417–430.

- Hannam, James (2023). The Globe: How the Earth became Round. Reaktion Books.

- Heimpel, Wolfgang (1986). "The Sun at Night and the Doors of Heaven in Babylonian Texts". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 38 (2): 127–151. doi:10.2307/1359796. JSTOR 1359796.

- Hezser, Catherine (2023). "Outer Space in Ancient Jewish and Christian Literature". In Mazur, Eric Michael; Taylor, Sarah McFarland (eds.). Religion and Outer Space. Taylor & Francis. pp. 9–24.

- Horowitz, Wayne (1988). "The Babylonian Map of the World". Iraq. 50: 147–165. doi:10.2307/4200289. JSTOR 4200289.

- Horowitz, Wayne (1998). Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography. Eisenbrauns.

- Horowitz, Wayne (2015). "Mesopotamian Cosmogony and Cosmology". In Ruggles, Clive L.N. (ed.). Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer. pp. 1823–1827. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_186. ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1.

- Johnson, David M. (1999). "Hesiod's Descriptions of Tartarus ("Theogony" 721-819)". Phoenix. 53 (1): 8–28. doi:10.2307/1088120. JSTOR 1088120.

- Keyser, Paul (2020). "The Kozy Kosmos of Early Cosmology". In Roller, Duane W. (ed.). New Directions in the Study of Ancient Geography. Eisenbrauns. pp. 5–55.

- Kim, Brittany (2020). "Stretching Out the Heavens: The Background and Use of a Creational Metaphor". In Miglio, Adam E.; Reeder, Caryn A.; Walton, Joshua T.; Way, Kenneth C. (eds.). For Us, but Not to Us: Essays on Creation, Covenant, and Context in Honor of John H. Walton. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 37–56.

- Klein, Cecelia F. (2006). "Woven Heaven, Tangled Earth A Weaver's Paradigm of the Mesoamerican Cosmos". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 385 (1): 1–35.

- Kochańczyk-Bonińska, Karolina (2016). "The Concept Of The Cosmos According To Basil The Great's On The Hexaemeron" (PDF). Studia Pelplinskie. 48: 161–169.

- Kulik, Alexander (2019). "The enigma of the five heavens and early Jewish cosmology". Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha. 28 (4): 239–266. doi:10.1177/0951820719861900.

- Lambert, Wilfred (2013). Babylonian Creation Myths. Eisenbrauns.

- Lambert, Wilfred (2016). "The Cosmology of Sumer and Babylon". Ancient Mesopotamian Religion and Mythology: Selected Essays. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 108–122.

- Panaino, Antonio (1995). "Uranographia Iranica I. The Three Heavens in the Zoroastrian Tradition and the Mesopotamian Background". In Gyselen, R. (ed.). Au carrefour des religions. Mélanges offerts à Philippe Gignoux. Peeters. pp. 205–225.

- Panaino, Antonio C.D. (2019). A Walk through the Iranian Heavens: Spherical and Non-Spherical Cosmographic Models in the Imagination of Ancient Iran and Its Neighbors. Brill.

- Rappenglück, Barbara (2004). "The Material of the Solid Sky and its Traces in Culture" (PDF). Culture and Cosmos. 8: 321–332.

- Robbins, Frank Egleston (1912). The Hexaemeral Literature: A Study of the Greek and Latin Commentaries on Genesis. University of Chicago Press.

- Rochberg, Francesca (2008). "Mesopotamian Cosmology". Cosmology: Historical, Literary, Philosophical, Religious, and Scientific Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 37–52.

- Rochberg, Francesca (2020). "Mesopotamian Cosmology". In Snell, Daniel C. (ed.). A Companion to the Ancient Near East. Wiley. pp. 305–320.

- Sarna, Nahum (1966). Understanding Genesis: Through Rabbinic Tradition and Modern Scholarship. The Jewish Theological Seminary Press.

- Seely, Paul H. (1991). "The firmament and the water above: Part I: The meaning of raqia in Gen 1:6-8" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal. 53: 227–240.

- Seely, Paul H. (1992). "The firmament and the water above: part 2: the meaning of "The water above the firmanent" in Gen 1:6-8". Westminster Theological Journal. 54: 31–46.

- Seely, Paul H. (1997). "The Geographical Meaning of "Earth" and" Seas" in Genesis 1:10" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal. 59: 231–256.

- Simon-Shoshan, Moshe (2008). ""The Heavens Proclaim the Glory of God..." A Study in Rabbinic Cosmology" (PDF). Bekhol Derakhekha Daehu–Journal of Torah and Scholarship. 20: 67–96.

- Tabatabaʾi, Mohammad Ali; Mirsadri, Saida (2016). "The Qurʾānic Cosmology, as an Identity in Itself". Arabica.

- Talon, Philippe (2001). "Enūma Eliš and the Transmission of Babylonian Cosmology to the West". Melammu. 2: 265–278.

- Tamtik, Svetlana (2007). "Enuma Elish: The Origins of Its Creation". Studia Antiqua. 5 (1): 65–76.

- Tumara, Nebojsa (2024). "Creation in Syriac Christianity". In Goroncy, Jason (ed.). T&T Clark Handbook of the Doctrine of Creation. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 164–175.

- Van der Sluijs, Marinus Anthony (2020). "The Ins and Outs of Gilgameš's Passage through Darkness". Talanta. 52: 7–36.

- Wright, Edward J. (2000). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press.

Further reading[edit]

- Assman, Jan. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, Cornell University Press, 2001, pp. 53–82.

- Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford University Press, 1998.

- George, A. Babylonian Topographical Texts, Peeters, 1992.

- Hunger, Hermann, and John Steele, The Babylonian Astronomical Compendium MUL.APIN, Routledge, 2018.

- Jacobsen, Thorkild. "The Cosmos as a State" in The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man: An Essay of Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near East, University of Chicago Press, 1977.

- Lambert, Wilfred. "Mesopotamian Creation Stories" in Imagining Creation, Brill, 2008, pp. 15–59.

- Sjöberg, Å. "In the beginning" in Riches Hidden in Secret Places: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Memory of Thorkild Jacobsen, Eisenbrauns, 2002, pp. 229–247.

- Wiggermann, F. "Mythological foundations of nature" in Natural Phenomena: Their Meaning, Depiction and Description in the Ancient Near East, 1992.

- Zago, Silvia. A Journey through the Beyond: The Development of the Concept of Duat and Related, Lockwood Press, 2022.