2018 Winter Olympics

Emblem of the 2018 Winter Olympics | |

| Host city | Pyeongchang, South Korea |

|---|---|

| Motto |

|

| Nations | 93[note 1] |

| Athletes | 2,922 (1,680 men and 1,242 women) |

| Events | 102 in 7 sports (15 disciplines) |

| Opening | 9 February 2018 |

| Closing | 25 February 2018 |

| Opened by | |

| Cauldron | |

| Stadium | Pyeongchang Olympic Stadium |

Winter Summer

2018 Winter Paralympics | |

| Pyeongchang Winter Olympics | |

| Hangul | 평창 동계 올림픽 대회 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 平昌冬季올림픽大會 |

| Revised Romanization | Pyeongchang Donggye Ollimpik Daehoe |

| McCune–Reischauer | P'yŏngch'ang Tonggye Ollimp'ik Taehoe |

| XXIII Olympic Winter Games | |

| Hangul | 제23회 동계 올림픽 대회 |

| Hanja | 第二十三回冬季올림픽大會 |

| Revised Romanization | Jeisipsamhoe Donggye Ollimpik Daehoe |

| McCune–Reischauer | Cheisipsamhoe Tonggye Ollimp'ik Taehoe |

| Part of a series on |

| 2018 Winter Olympics |

|---|

The 2018 Winter Olympics (Korean: 2018년 동계 올림픽, romanized: Icheon sip-pal nyeon Donggye Ollimpik), officially the XXIII Olympic Winter Games (French: Les XXIIIes Jeux olympiques d'hiver;[note 2] Korean: 제23회 동계 올림픽, romanized: Jeisipsamhoe Donggye Ollimpik) and also known as PyeongChang 2018 (Korean: 평창2018, romanized: Pyeongchang Icheon sip-pal), were an international winter multi-sport event held between 9 and 25 February 2018 in Pyeongchang, South Korea, with the opening rounds for certain events held on 8 February, a day before the opening ceremony.

Pyeongchang was elected as the host city for the 2018 Winter Games at the 123rd IOC Session in Durban, South Africa in July 2011. This marked the second time that South Korea had hosted the Olympic Games (having previously hosted the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul), as well as the first time it hosted the Winter Olympics. The 2018 Games marked the third time that an Asian country had hosted the Winter Olympics, after Sapporo 1972 and Nagano 1998, both in Japan. It was also the first Winter Olympics held in mainland Asia, and the first of three consecutive Olympic Games held in East Asia, preceding the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics in Japan and the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics in China.

The 2018 Games featured 102 events over 15 disciplines, a record number of events for the Winter Games. This is the first edition in Winter Olympic Games history to feature more than 100 medal events, four of which made their Olympic debut in 2018: "big air" snowboarding, mass start speed skating, mixed doubles curling, and mixed team alpine skiing. A total of 2,914 athletes from 93[note 1] teams competed, with the national debuts of Ecuador, Eritrea, Kosovo, Malaysia, Nigeria and Singapore.

After a state-sponsored doping program was exposed following the 2014 Winter Olympics, the Russian Olympic Committee was suspended, but selected athletes were allowed to compete neutrally under the special IOC designation of "Olympic Athletes from Russia" (OAR), provided they could meet certain anti-doping requirements. North Korea agreed to participate in the Games in spite of tense relations with South Korea. The two nations paraded together at the opening ceremony as a unified Korea, and fielded a unified team (COR) in the women's ice hockey.

South Korea ranked seventh overall at the 2018 Winter Games, with five gold medals and 17 overall medals. South Korea has traditionally been a country that won many medals in short track speed skating, but in this competition, it also won medals in skeleton racing, curling and skiing. South Korea's Yun Sung-Bin won a gold medal in men's skeleton racing, the first Olympic gold ever won by Asia in the sledding event. Norway led the total medal tally with 39, followed by Germany at 31 and Canada at 29.[1] Germany and Norway were tied for the highest number of gold medals, both winning 14.

Bidding and election[edit]

Pyeongchang was elected as the host city at the 123rd IOC Session in Durban, South Africa, on 6 July 2011, earning the necessary majority of at least 48 votes in just one round of voting.[2] Winning 63 of the 95 votes cast in the first secret ballot, Pyeongchang received more votes than its competitors combined, overwhelmingly beating Munich in Germany, which received 25 votes, and Annecy in France, which received seven.[3][4]

This was South Korea's third consecutive bid for the Winter Olympics, having been defeated by Vancouver and Sochi respectively in the final rounds of voting for the 2010 and 2014 Games.[3] Earlier, PyeongChang lost to Vancouver with a difference of 3 votes in bidding the 2010 Olympics, and lost to Sochi with a difference of 4 votes in bidding the 2014 Olympics. Since then, South Korea made great progress in preparing to host the Winter Olympics and succeeded in hosting the 2018 Olympics after three challenges.[4]

After winning the election, Pyeongchang became the third Asian city to host the Winter Olympics.[2][3] Also, South Korea became the second country in Asia to host both the Summer (1988 Seoul Olympics) and Winter Olympics.

| City | Nation | Votes |

|---|---|---|

| Pyeongchang | 63 | |

| Munich | 25 | |

| Annecy | 7 |

Development and preparation[edit]

On 5 August 2011, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced the formation of the Pyeongchang 2018 Coordination Commission.[6][7] On 4 October 2011, it was announced that the Organizing Committee for the 2018 Winter Olympics would be headed by Kim Jin-sun. The Pyeongchang Organizing Committee for the 2018 Olympic & Paralympic Winter Games (POCOG) was launched at its inaugural assembly on 19 October 2011. The first tasks of the organizing committee were putting together a master plan for the Games as well as forming a design for the venues.[8] The IOC Coordination Commission for the 2018 Winter Olympics made their first visit to Pyeongchang in March 2012. By then, construction was already underway on the Olympic Village.[9][10] In June 2012, construction began on a high-speed rail line that would connect Pyeongchang to Seoul.[11]

The International Paralympic Committee met for an orientation with the Pyeongchang 2018 organizing committee in July 2012.[12] Then-IOC President Jacques Rogge visited Pyeongchang for the first time in February 2013.[13]

The Pyeongchang Organizing Committee for the 2018 Olympic & Paralympic Winter Games created Pyeongchang WINNERS in 2014 by recruiting university students living in South Korea to spread awareness of the Olympic Games through social networking services and news articles.[14]

Medals[edit]

The design for the Games' medals was unveiled on 21 September 2017. Created by Lee Suk-woo, the design features a pattern of diagonal ridges on both sides, with the Olympic rings on the front, and the obverse showing the 2018 Olympics' emblem, the event name and the discipline. The edge of each medal is marked with extrusions of hangul alphabets, while the ribbons are made from a traditional South Korean textile.[15] Gold medals contained 99 percent of silver and 1 percent of gold, which is a traditional composition for Olympic gold medals. At 586 grams (20.7 oz) they were the heaviest medals in the Olympic history.[16][17]

Torch relay[edit]

The torch relay started on 24 October 2017 in Greece and lasted for 101 days, ending at the start of the Olympics on 9 February 2018. The Olympic torch entered South Korea on 1 November 2017. There were 7,500 torch bearers to represent the combined Korean population of approximately 75 million people. There were also 2,018 support runners to guard the torch and act as messengers.

The torch and its bearers traveled by a diverse means of transportation, including by turtle ship in Hansando Island, sailboat on the Baengmagang River in Buyeo, marine cable car in Yeosu, zip-wire over Bamseom Island, steam train in the Gokseong Train Village, marine rail bike along the east coast in Samcheok, and by yacht in Busan Metropolitan City.

There were also robot torch relays in Jeju and Daejeon.[18]

Venues[edit]

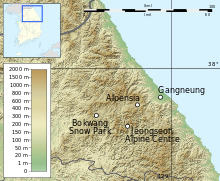

Most of the outdoor snow events were held in the county of Pyeongchang, while some of the alpine skiing events took place in the neighboring county of Jeongseon. The indoor ice events were held in the nearby city of Gangneung.

Pyeongchang (mountain cluster)[edit]

The Alpensia Sports Park in Daegwallyeong-myeon, Pyeongchang, was the focus of the 2018 Winter Olympics.[19][20] It was home to the Olympic Stadium,[21] the Olympic Village and most of the outdoor sports venues.

- Alpensia Ski Jumping Centre – ski jumping, Nordic combined, snowboarding (big air)

- Alpensia Biathlon Centre – biathlon

- Alpensia Cross-Country Skiing Centre – cross-country skiing, Nordic combined

- Alpensia Sliding Centre – luge, bobsleigh, skeleton

- Yongpyong Alpine Centre – alpine skiing (slalom, giant slalom)

Additionally, a stand-alone outdoor sports venue was located in Bongpyeong-myeon, Pyeongchang:

- Phoenix Snow Park – freestyle skiing, snowboarding

Another stand-alone outdoor sports venue was located in neighboring Jeongseon county:

- Jeongseon Alpine Centre – alpine skiing (downhill, super-G, combined)

Gangneung (coastal cluster)[edit]

The Gangneung Olympic Park, in the neighborhood of Gyo-dong in Gangneung city, includes four indoor sports venues, all in close proximity to one another.

- Gangneung Hockey Centre – ice hockey (men's competition)

- Gangneung Curling Centre – curling

- Gangneung Oval[21] – long track speed skating

- Gangneung Ice Arena – short track speed skating, figure skating

In addition, a stand-alone indoor sports venue was located in the grounds of Catholic Kwandong University.

- Kwandong Hockey Centre – ice hockey (women's competition)

Ticketing[edit]

Ticket prices for the 2018 Winter Olympics were announced in April 2016 and tickets went on sale in October 2016. Event tickets ranged in price from ₩20,000 South Korean won (approx. US$17) to ₩900,000 (~US$787) while tickets for the opening and closing ceremonies ranged from ₩220,000 (~US$192) to ₩1.5 million (~US$1311). The exact prices were determined through market research; around 50% of the tickets were expected to cost about ₩80,000 (~US$70) or less, and tickets in sports that are relatively unknown in the region, such as biathlon and luge, were made cheaper in order to encourage attendance. By contrast, figure skating and the men's ice hockey gold-medal game carried the most expensive tickets of the Games.[22]

As of 11 October 2017, domestic ticket sales for the Games were reported to be slow. Of the 750,000 seats allocated to South Koreans, only 20.7% had been sold. International sales were more favorable, with 59.7% of the 320,000 allocated tickets sold.[23][24] However, as of 31 January 2018, 77% of all tickets had been sold.[25]

The Games[edit]

Opening ceremony[edit]

The opening ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics was held at the Pyeongchang Olympic Stadium on 9 February 2018. The US$100 million facility was only intended to be used for the opening and closing ceremonies of these Olympics and the subsequent Paralympics; it was demolished following their conclusion.[26][27][28]

Sports[edit]

The 2018 Winter Olympics featured 102 events over 15 disciplines in 7 sports,[29] making it the first Winter Olympics to surpass 100 medal events. Six new events in existing sports were introduced to the Winter Olympic program in Pyeongchang: men's and ladies' big air snowboarding, mixed doubles curling, men's and ladies' mass start speed skating, and mixed team alpine skiing.[29][30]

| 2018 Winter Olympic sports program | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of medal events contested in each separate discipline.

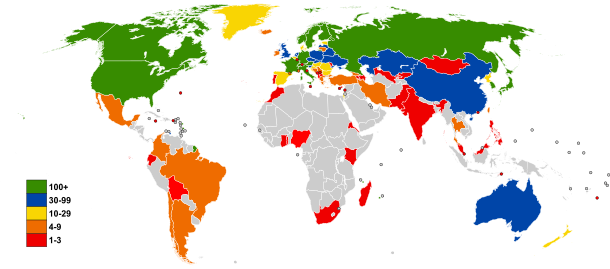

Participating National Olympic Committees[edit]

A record total of 93[note 1] teams qualified at least one athlete to compete in the Games. The number of athletes who qualified per country is listed in the table below (number of athletes shown in parentheses). Six nations made their Winter Olympics debuts: Ecuador, Eritrea, Kosovo, Malaysia, Nigeria and Singapore.[31] Athletes from three further countries – the Cayman Islands, Dominica, and Peru – qualified to compete, but all three National Olympic Committees returned the quota spots back to the International Ski Federation (FIS).[32]

Under a historic agreement facilitated by the IOC, qualified athletes from North Korea were allowed to cross the Korean Demilitarized Zone into South Korea to compete in the Games.[33][34][35] The two nations marched together under the Korean Unification Flag during the opening ceremony.[36][37] A unified Korean team, consisting of 12 players from North Korea and 23 from South Korea, competed in the women's ice hockey tournament under a special IOC country code designation (COR) following talks in Panmunjom on 17 January 2018.[36] The two nations also participated separately: the South Korea team competed in every sport, while the North Korea team competed in alpine skiing, cross-country skiing, figure skating, and short track speed skating.[38]

On 5 December 2017, the IOC announced that the Russian Olympic Committee had been suspended due to the Russian doping scandal and the investigation into the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Individual Russian athletes, who qualified and could demonstrate they had complied with the IOC's doping regulations, were given the option to compete at the 2018 Games as "Olympic Athletes from Russia" (OAR) under the Olympic flag and with the Olympic anthem played at any ceremony.[39]

Number of athletes by National Olympic Committee[edit]

a Apart from the respective delegations, North Korea and South Korea formed a unified Korean women's ice hockey team.

b Russian athletes were entitled to participate as Olympic Athletes from Russia (OAR) if individually cleared by the IOC.

Event scheduling[edit]

The IOC has allowed NBC to influence the Olympic event scheduling to maximize U.S. television ratings when possible, due to the substantial fees paid by NBC for rights to the Olympics (which have been extended through 2032 with a nearly $8 billion agreement), the company being one of IOC's major sources of revenue.[46][47] As figure skating is one of the most popular Winter Olympic sports among U.S. viewers, the figure skating events were scheduled with morning start times to accommodate primetime broadcasts in the Americas. This scheduling practice affected the events themselves, including skaters having to adjust to the modified schedule, as well as attendance levels at the sessions.[48]

Conversely, and somewhat controversially, eight of the eleven biathlon events were scheduled at night, making it necessary for competitors to ski and shoot under floodlights, with colder temperatures and blustery winds.[49]

Calendar[edit]

| OC | Opening ceremony | ● | Event competitions | 1 | Event finals | EG | Exhibition gala | CC | Closing ceremony |

| February | 8th Thu |

9th Fri |

10th Sat |

11th Sun |

12th Mon |

13th Tue |

14th Wed |

15th Thu |

16th Fri |

17th Sat |

18th Sun |

19th Mon |

20th Tue |

21st Wed |

22nd Thu |

23rd Fri |

24th Sat |

25th Sun |

Events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | CC | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 11 | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |||||||||||

| ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 12 | ||||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| ● | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | ● | 1 | EG | 5 | ||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 2 | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||

| ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 1 | ● | ● | 1 | 2 | ||||

| ● | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | |||||||||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | ● | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| ● | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ● | ● | 1 | 3 | 10 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 14 | ||||||||

| Daily medal events | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 102 | |

| Cumulative total | 0 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 18 | 26 | 30 | 39 | 46 | 55 | 61 | 64 | 69 | 76 | 86 | 90 | 98 | 102 | ||

| February | 8th Thu |

9th Fri |

10th Sat |

11th Sun |

12th Mon |

13th Tue |

14th Wed |

15th Thu |

16th Fri |

17th Sat |

18th Sun |

19th Mon |

20th Tue |

21st Wed |

22nd Thu |

23rd Fri |

24th Sat |

25th Sun |

Total events | |

Medal table[edit]

* Host nation (South Korea[50])

| Rank | NOC | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 39 | |

| 2 | 14 | 10 | 7 | 31 | |

| 3 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 29 | |

| 4 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 23 | |

| 5 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 20 | |

| 6 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 14 | |

| 7 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 17 | |

| 8 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 15 | |

| 9 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 15 | |

| 10 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 14 | |

| 11–30 | Remaining | 20 | 29 | 41 | 90 |

| Totals (30 entries) | 103 | 102 | 102 | 307 | |

Podium sweeps[edit]

Three podium sweeps were recorded during the Games.

| Date | Sport | Event | NOC | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 February | Speed skating | Women's 3000 metres | Carlijn Achtereekte | Ireen Wüst | Antoinette de Jong | [51] | |

| 11 February | Cross-country skiing | Men's 30 km skiathlon | Simen Hegstad Krüger | Martin Johnsrud Sundby | Hans Christer Holund | [52] | |

| 20 February | Nordic combined | Individual large hill/10 km | Johannes Rydzek | Fabian Rießle | Eric Frenzel | [53] |

Records[edit]

- Noriaki Kasai of Japan became the first athlete in history to participate in eight Winter Olympics when he took part in the ski jumping qualification the day before the opening of the Games.[54] The previous record of seven Winter Olympics was held by Russian luger Albert Demchenko.

- Japanese athlete Yuzuru Hanyu became the fourth male figure skater (after Gillis Grafström, Karl Schäfer, and Dick Button) to win two consecutive Olympic gold medals.

- American Nathan Chen became the first figure skater to land five quadruple jumps in one program.[55]

- German figure skaters Aliona Savchenko and Bruno Massot set a new ISU best free skating score of 159.31 in pair skating.[56]

- Canadian figure skaters Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir became the most decorated figure skaters in Olympic history with a total of 5 medals.

- Canadian figure skaters Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir set a new ISU best short dance score of 83.67[57] and a new ISU best combined total score of 206.07[58] in ice dance. French ice dancers Gabriella Papadakis and Guillaume Cizeron set a new ISU best free dance score of 123.35.[59]

- Russian figure skater Alina Zagitova set a new ISU best short program score of 82.92 in Ladies' single skating.[60]

- Dutch speed skater Sven Kramer won gold in the men's 5000 m event, becoming the only male speed skater to win the same Olympic event three times. He was also the first man to win a total of eight Olympic medals in speed skating.[61]

- Dutch speed skater Ireen Wüst won an individual gold medal for the fourth Olympics in a row, the first time this had been achieved by a Winter Olympian. She also became the first speed skater (male or female) to win ten Winter Olympic medals and the first female Winter Olympian to win nine individual medals.[62]

- Chinese short track speed skater Wu Dajing beat the men's 500 m world record twice en route to winning a gold medal, becoming only the second person in history to skate the discipline in under 40 seconds (after American J. R. Celski), and the first to achieve this at "sea level".[63]

- Dutch athlete Jorien ter Mors became the first female athlete to win Olympic medals in two different sports at a single Winter Games;[64] she won a speed skating gold medal in the 1000 m and she was also part of the Dutch short track team that won bronze in the 3000 m relay.

- Ester Ledecká of the Czech Republic won gold in the super-G skiing event and another gold in the snowboarding parallel giant slalom, making her the first female athlete to win Olympic gold medals in two different sports at a single Winter Games.[65]

- Norwegian cross-country skier Marit Bjørgen won bronze in the women's team sprint and gold in the 30 km classical event, bringing her total Olympic medal haul to fifteen, the most won by any athlete (male or female) in Winter Olympics history.[66] The record was previously held by fellow Norwegian athlete Ole Einar Bjørndalen who has thirteen Olympic medals.

- Germany and Canada tied for gold in the two-man bobsleigh event, only the second time in history that two countries had tied for a gold medal in this particular event, the first time being in the 1998 Winter Olympics twenty years earlier.[67]

- Norway won a total of 39 medals, setting a new record for the highest number of medals won at a single Winter Olympics. Their 39th medal was the last gold medal won by cross-country skier Marit Bjørgen in the 30 km classical event. The record was previously held by the USA who won 37 medals in Vancouver 2010.[68]

Closing ceremony[edit]

The closing ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics was held at the Pyeongchang Olympic Stadium on 25 February 2018. IOC president Thomas Bach declared the Games closed, and the cauldron was extinguished. The Olympic flag was handed to Beijing, the next host city of the Winter Olympics.

Broadcasting[edit]

Broadcast rights to the 2018 Winter Olympics were already sold in some countries as part of long-term broadcast rights deals, including the Games' local rightsholder SBS, which in July 2011 had extended its rights to the Olympics through 2024.[69] SBS sub-licensed its rights to MBC and KBS.[70]

On 29 June 2015, the IOC announced that Discovery Communications (now Discovery, Inc.) had acquired exclusive rights to the Olympics across all of Europe (excluding Russia) from 2018 through 2024. Discovery's pan-European Eurosport channels were promoted as the main broadcaster of the Games, but Discovery's free-to-air channels such as DMAX in Spain,[71] Kanal 5 in Sweden, and TVNorge in Norway, were also involved in the overall broadcasting arrangements.[72] Discovery was required to sub-license at least 100 hours of coverage to free-to-air broadcasters in each market;[73][74] some of these agreements required certain sports to be exclusive to Eurosport and its affiliated networks.[75] The deal did not initially cover France due to the broadcast rights of France Télévisions, which run through to the 2020 Games.[76] In the United Kingdom, Discovery held exclusive pay television rights under licence from the BBC, in return for the BBC sub-licensing the free-to-air rights to the 2022 and 2024 Olympics from Discovery.[77]

Russian state broadcaster Channel One, and sports channel Match TV, committed to covering the Games with a focus on Russian athletes.[76] Russia was not affected by the Eurosport deal, due to a pre-existing contract held by a marketing agency which extends to 2024.[76]

In the United States, the Games were once again broadcast by NBCUniversal properties under a long-term contract and for the first time ever that the Super Bowl and the Winter Olympics will be held on NBC on the same year.[78][79] On 28 March 2017, NBC announced that it would adopt a new format for its primetime coverage of the 2018 Winter Olympics, with a focus on live coverage in all time zones to take advantage of Pyeongchang's 14-hour difference with U.S. Eastern Time (and 17-hour difference with U.S. Pacific Time), and to address criticism of its previous tape delay practices. As before, the primetime block began at 8:00 p.m. ET (5:00 p.m. PT), and unlike previous Olympics, was available for streaming. Figure skating events were deliberately scheduled with morning sessions so they could be aired during primetime in the Americas (and in turn, NBC's coverage; due to the substantial fees NBC has paid for rights to the Olympics, the IOC has allowed NBC to have influence on event scheduling to maximize U.S. television ratings when possible; NBC agreed to a $7.75 billion contract extension on 7 May 2014, to air the Olympics through the 2032 games,[46] is also one of the major sources of revenue for the IOC).[47][48] Coverage took a break in the East for late local news, after which coverage continued into "Primetime Plus", featuring additional live coverage into the Eastern late night and Western primetime hours.

NHK and Olympic Broadcasting Services (OBS) once again filmed portions of the Games in high-dynamic-range 8K resolution video, including 90 hours of footage of selected events and the opening ceremonies.[80][81] ATSC 3.0 digital terrestrial television, using 4K resolution, was introduced in South Korea in 2017 in time for the Olympics.[82][83] This footage was delivered in 4K in the U.S. by NBCUniversal parent Comcast to participating television providers, including its own Xfinity, as well as DirecTV and Dish Network. NBC's Raleigh-based affiliate WRAL-TV also held demonstration viewings as part of its ATSC 3.0 test broadcasts.[84][85][86]

The 2018 Winter Olympics were used to showcase 5G wireless technologies, as part of a collaboration between domestic wireless sponsor KT, and worldwide sponsor Intel. Several venues were outfitted with 5G networks to facilitate features such as live camera feeds from bobsleds, and multi-camera views from cross-country and figure skating events. These were offered as part of public demonstrations coordinated by the two sponsors.[87][88]

The winners of the Olympic Golden Rings Awards were announced in June 2019. There were 75 pieces of broadcast content from the 2018 Olympics submitted over ten categories (plus one category for the 2018 Youth Olympics). NBC won a total of eight awards, winning four of the main categories: Best Olympic Feature, Best Olympic Digital Service, Best Olympic program and Best Documentary Film; they came second in the Best On-Air Promotion and Best Social Media Content/Production categories. Discovery/Eurosport won four categories: Best On-Air Promotion, Best Production Design, Best Innovation and Best Social Media Content/Production; they also came second in the Best Olympic Digital Service category. The BBC and NHK took the other two main awards: Most Sustainable Operation and Best Athlete Profile respectively. The title of Best Feature at the Youth Olympic Games Buenos Aires 2018 was also awarded to the BBC.[89]

Marketing[edit]

The official emblem, reflecting ice crystals and derived from the hangul letters ㅍ and ㅊ—the initial sounds of "Pyeong" and "Chang"—was unveiled on 3 May 2013.[90] In all official materials, the name of the host city was stylized in CamelCase as "PyeongChang", in order to alleviate potential confusion with Pyongyang, the similarly named capital of neighboring North Korea.[91]

New international sponsorship deals also debuted in Pyeongchang: Toyota was introduced as the new "Mobility" sponsor of the Olympics, although the company waived its domestic sponsorship to the local competitors Hyundai and Kia due to their support of the Pyeongchang bid.[92][93][94][95][96] Alibaba Group and Intel also debuted as e-commerce/cloud services and technology sponsors respectively.[97][98]

Concerns and controversies[edit]

North–South Korean relations[edit]

Due to the state of relations between North and South Korea, concerns were raised over the security of the 2018 Winter Olympics, especially in the wake of tensions over North Korean missile and nuclear tests. On 20 September 2017, South Korean president Moon Jae-in stated that the country would ensure the security of the Games.[99] The next day, Laura Flessel-Colovic, the French Minister of Youth Affairs and Sports, stated that France would pull out of the Games if the safety of its delegation could not be guaranteed.[100]

The next day, Austria and Germany raised similar concerns and also threatened to skip the Games. France later reaffirmed its participation.[101] In early December 2017, the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, told Fox News that it was an "open question" whether the United States was going to participate in the Games, citing security concerns in the region.[102] However, days later the White House Press Secretary, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, stated that the United States would participate.[103]

In his New Year's address on 1 January 2018, North Korean leader Kim Jong-un proposed talks in Seoul over the country's participation in the Games, which would be the first high-level talks between the North and South in over two years. Because of the talks, held on 9 January, North Korea agreed to field athletes in Pyeongchang.[104][105] On 17 January 2018, it was announced that North and South Korea had agreed to field a unified Korean women's ice hockey team at the Games, and to enter together under a Korean Unification Flag during the opening ceremony.[36][106]

These moves were met with opposition in South Korea, including protests and online petitions; critics argued that the government was attempting to use the Olympics to spread pro-North Korean sentiment, and that the unified ice hockey team would fail.[107] A rap video entitled "The Regret for Pyeongchang" (평창유감), which echoed this criticism and called the event the "Pyongyang Olympics", went viral in the country.[108] Japan's foreign affairs minister Tarō Kōno warned South Korea to be wary of North Korea's "charm offensive", and not to ease its pressure on the country.[36][109]

The South Korean President, Moon Jae-in, at the start of the Olympics shook hands with Kim Yo-jong, the sister of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and a prominent figure of the regime. This marked the first time since the Korean War that a member of the ruling Kim dynasty had visited South Korea.[110][111] In contrast, U.S. vice president Mike Pence met with Fred Warmbier (father of Otto Warmbier, who had died after being released from captivity in North Korea) and a group of North Korean defectors in Pyeongchang.[112] American officials said that North Korea cancelled a meeting with Pence at the last minute.[113]

At the closing ceremony, North Korea sent general Kim Yong-chol as its delegate. His presence was met with hostility from South Korean conservatives, as there were allegations that he had a role in the ROKS Cheonan sinking and other past attacks. The Ministry of Unification stated that "there is a limitation in pinpointing who was responsible for the incident." Although he is subject to sanctions, they did not affect his ability to visit the country for the Games.[114][115]

Russian doping[edit]

Russia's participation in the 2018 Winter Olympics was affected by the aftermath of its state-sponsored doping program. As a result, the IOC suspended the Russian Olympic Committee in December 2017, although Russian athletes whitelisted by the IOC were allowed to compete neutrally under the OAR (Olympic Athletes from Russia) designation.[116] The official sanctions imposed by the IOC included: the exclusion of Russian government officials from the Games; the use of the Olympic flag and Olympic Anthem in place of the Russian flag and anthem; and the submission of a replacement logo for the OAR uniforms.[117]

By early January 2018, the IOC had banned 43 Russian athletes from competing in the 2018 Winter Olympics and all future Olympic Games (as part of the Oswald Commission). Of those athletes, 42 appealed against their bans to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and 28 of the appeals were successful, but eleven of the athletes had their sanctions upheld due to the weight of evidence against them. The IOC found it important to note that CAS Secretary General "insisted that the CAS decision does not mean that these 28 athletes are innocent" and that they would consider an appeal against the court's decision. Hearings for the remaining three athletes were postponed.[118]

The eventual number of neutral Russian athletes that participated at the 2018 Games was 168. These were selected from an original pool of 500 athletes that was put forward for consideration and, in order to receive an invitation to the Games, they were obliged to meet a number of pre-games conditions. Two athletes, who met the conditions and were cleared by the IOC, subsequently failed drug tests during the Games.

Russian president Vladimir Putin and other officials had signalled in the past that it would be a humiliation if Russian athletes were not allowed to compete under the Russian flag.[119] However, there were never actually any official plans to boycott the 2018 Games[116] and in late 2017 the Russian government agreed to allow their athletes to compete at the Games as individuals under a neutral designation.[120][121] Despite this public show of co-operation, there were numerous misgivings voiced by leading Russian politicians, including a statement from Putin himself saying that he believed the United States had used its influence within the IOC to "orchestrate the doping scandal".[122] 86% of the Russian population opposed participation at the Olympics under a neutral flag,[123] and many Russian fans attended the Games wearing the Russian colors and chanting "Russia!" in unison, in an act of defiance against the ban.[124]

The IOC's decision was heavily criticized by Jack Robertson, primary investigator of the Russian doping program on behalf of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), in whose opinion the judgement was commercially and politically motivated. He argued that not only was doping rife among Russian athletes but that there was no sign of it being eradicated.[125] The CAS decision to overturn the life bans of 28 Russian athletes and restore their medals was also fiercely criticized, by Olympic officials, IOC president Thomas Bach and whistleblower Grigory Rodchenkov's lawyer.[126]

See also[edit]

- 2018 Winter Paralympics

- Olympic Games celebrated in South Korea

- 1988 Summer Olympics – Seoul

- 2018 Winter Olympics – Pyeongchang

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Who won Team Canada's 29 medals in PyeongChang?". olympic.ca. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Pyeongchang picked to host 2018 Winter Games". ESPN.com. 6 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Longman, Jeré; Sang-hun, Choe (6 July 2011). "2018 Winter Games to Be Held in Pyeongchang, South Korea". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hersh, Philip (6 July 2011). "Pyeongchang wins 2018 Winter Olympics". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017.

- ^ "IOC's PyeongChang 2018 Page (look at More About the Election tab)". International Olympic Committee. 6 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Gunilla Lindberg to Chair PyeongChang 2018 Coordination Commission". Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Coordination Commissions". Olympic.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "PyeongChang 2018 Organizing Committee Launched". Archived from the original on 20 October 2011.

- ^ "PyeongChang 2018 Praised". Gamesbids.com. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 have "good grasp of what is expected" says Lindberg after first IOC Coordination Commission visit". Insidethegames.biz. 22 March 2012. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Construction Begins on High-Speed Railway, Critical for PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Games". Gamesbids.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "IPC Orientates PyeongChang 2018". Gamesbids.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 on "right track" declares Rogge after first visit". Insidethegames.biz. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 recruits college student reporters: WINNERS". visitkorea.or.kr. 18 June 2015. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 unveil Olympic Games medals". Inside the Games. 21 September 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Zaccardi, Nick (20 September 2017). "PyeongChang Olympic medals believed to be heaviest ever (photos)". NBC Sports. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Самая золотая, самая крупная и самая тяжелая. История олимпийских медалей Archived 23 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Tass.ru (in Russian). 22 July 2021

- ^ "PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Torch Relay". PyeongChang 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "PyeongChang 2018 Alpensia Resort and water park complete and full for summer season". Sportsfeatures.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Pyeongchang2018 Volume 2 (Sport and Venues)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Pyeongchang 2018 move venue for Opening and Closing Ceremonies | Winter Olympics 2018". insidethegames.biz. 6 July 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 reveal ticket prices for Winter Olympic Games". 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016.

- ^ "PyeongChang Olympics ticket sales get icy reception". The Korea Herald. 11 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 announce improved ticket sales for Olympics and Paralympics". Inside the Games. 21 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018 announce expected ticket sales for 100% Olympics and Paralympics". Yonhap. 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Horwitz, Josh. "South Korea's $100 million Winter Olympics stadium will be used exactly four times". Quartz. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Boram, Kim (9 February 2018). "(Olympics) S. Korean speed skater Mo Tae-bum takes Olympic Oath". Yonhap News Agency. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Korean figure skater Kim Yuna lights Olympic cauldron". Reuters. uk.reuters.com. 9 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Olympic - Schedule, Results, Medals and News". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016.

- ^ "Winter Olympics: Big air, mixed curling among new 2018 events". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ "6 New National Olympic Committees Welcomed to Winter Olympics for the First Time". PyeongChang 2018. 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ "Qualification Systems for XXII Olympic Winter Games, PyeongChang 2018 Alpine skiing" (PDF). FIS. 16 August 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Pyeongchang 2018: Athletes to travel through demilitarised zone". BBC Sport. 18 May 2017. Archived from the original on 20 May 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "North Korean skaters qualify for Pyeongchang 2018". insidethegames.biz. Dunsar Media Company Limited. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (8 January 2018). "North Korea to Send Athletes to Olympics in South Korea Breakthrough". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Koreas to march under single 'united' flag in Olympic Games". BBC News. 17 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Stiles, Matt (20 January 2018). "North Korea gets official OK to compete in Winter Olympics, will march with South". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California, United States. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "N. Korea to send 22 athletes in three sports to PyeongChang Winter Olympics: IOC". Yonhap News Agency. 18 January 2018. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

The team [Unified Korea women's ice hockey team] will use the acronym COR and will be the first joint Korean sports team at an Olympic Games.

- ^ "IOC suspends Russian NOC and creates a path for clean individual athletes to compete in Pyeongchang 2018 under the Olympic flag". IOC. 5 December 2017. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Alpine Skiing Quotas List for Olympic Games 2018". data.fis-ski.com. FIS. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "2018 Olympic Winter Games". iihf.com. IIHF. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Cross-country Quotas List for Olympic Games 2018". data.fis-ski.com. FIS. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter Games". worldcurling.org. WCF. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "ISU Communication no. 2136: XXIII Olympic Winter Games 2018 PyeongChang, Entries Speed Skating". isu.org. ISU. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "Quotas – Olympic Winter Games Pyeongchang 2018". IBSF. Archived from the original on 30 May 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ a b Armour, Nancy (7 May 2014). "NBC Universal pays $7.75 billion for Olympics through 2032". USA Today. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ a b Draper, Kevin (7 December 2017). "Fewer Russians Could Be a Windfall for U.S. Olympic Business". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ a b Longman, Jeré (12 February 2018). "For Olympic Figure Skaters, a New Meaning to Morning Routine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Biathletes battling difficult conditions at Winter Olympics". USA Today. Associated Press. 10 February 2018. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Medal Standings". Pyeongchang 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Speed Skating: Ladies' 3,000m – Medallists" (PDF). PyeongChang 2018. IOC. 10 February 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Cross-Country Skiing: Men's 15km + 15km Skiathlon – Medallists" (PDF). PyeongChang 2018. IOC. 11 February 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Nordic Combined: Individual Gundersen LH/10km – Medallists" (PDF). PyeongChang 2018. IOC. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ^ "Skispringer Kasai in olympische recordboeken" [Ski jumper Kasai in Olympic record books]. nu.nl. NOS. 8 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018.

- ^ Abad-Santos, Alex (16 February 2018). "Winter Olympics 2018: what makes US figure skater Nathan Chen so dominant". Vox. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Personal Best Scores – Pairs, Free Skating Score". isuresults.com. 15 February 2018. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018.

- ^ "Personal Best Scores – Ice Dance, Short Dance Score". isuresults.com. 19 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Personal Best Scores – Ice Dance, Total Score". isuresults.com. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Personal Best Scores – Ice Dance, Free Dance Score". isuresults.com. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018.

- ^ "Personal Best Scores – Ladies, Short Program Score". isuresults.com. 23 February 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018.

- ^ NBCOlympics (10 February 2018). "Dutch Speedskater Sven Kramer Wins 3rd Straight 5000m Olympic Gold". NBCChicago.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ Bushnell, Henry (12 February 2018). "Dutch speed skating GOAT [Greatest Of All Time] makes Michael Phelpsian Winter Olympics history". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Jennings, Simon (22 February 2018). "Short track: China's Wu wins 500m in world record time". Reuters. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Ter Mors medals in 2 different sports at same Winter Games". The China Post. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Falkingham, Katie (24 February 2018). "Winter Olympics: History-maker Ester Ledecka wins gold in two sports". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "Winter Olympics: Marit Bjorgen wins gold as Norway top the medal table". BBC Sport. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ Boylan-Pett, Liam (19 February 2018). "Canada and Germany tie in thrilling 2-man bobsled". nbcolympics.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018.

- ^ "Winter Olympics: Norway win record 38th medal as Switzerland take team alpine skiing gold". BBC Sport. 24 February 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "IOC awards SBS broadcast rights for 2018, 2020, 2022 and 2024 Olympic Games". International Olympic Committee. 9 December 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Kang Ah-young (20 September 2017). "언론사, 평창 동계올림픽 카운트다운" [Media, PyeongChang Winter Olympics Countdown]. journalist.or.kr (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ X. Migelez (19 December 2017). "DMAX emitirá los Juegos Olímpicos de invierno de Pyeongchang 2018. Noticias de Televisión" [DMAX to broadcast the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics]. El Confidencial (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Discovery looks ahead to Winter Olympics". Broadband TV News. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 11 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Ourand, John (29 June 2015). "Discovery Lands European Olympic Rights Through '24". sportsbusinessdaily.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "BBC dealt another blow after losing control of TV rights for Olympics". The Guardian. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Discovery confirms TLC coverage for PyeongChang 2018". SportsPro. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "Russian state broadcasters commit to PyeongChang coverage". Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "Olympics coverage to remain on BBC after Discovery deal". The Guardian. 2 February 2016. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Bob Costas steps down as NBC host of Olympics; Mike Tirico to replace him". USA Today. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Brennan: Bob Costas has been the face of the Olympics for Americans". USA Today. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Winter Olympics innovates with 8K HDR and live 5G production firsts". Archived from the original on 13 February 2018.

- ^ "SES Helps NBC Ship 4K/HDR Coverage from Winter Games". Multichannel. 13 February 2018. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "2018 A Crucial Year for ATSC 3.0". Archived from the original on 13 February 2018.

- ^ "The top tech at the 2018 Winter Olympics: 5G, VR, 4K, bullet time and SmartSuits". South China Morning Post. 3 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ "Can you watch the Winter Olympics in 4K and HDR? Comcast tells Ars "no" [Updated]". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Cain, Brooke (21 February 2018). "WRAL: ATSC 3.0 Next Generation TV delivers 4K ultra high-def". The News & Observer. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Greeley, Paul (21 February 2018). "WRAL Shows Olympics In Next Gen TV Format". TVNewsCheck. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ "PyeongChang will host first major 5G video demonstrations for Olympics viewers". VentureBeat. 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ "5G Is Making Its Global Debut at Olympics, and It's Wicked Fast". Bloomberg.com. 12 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ "Olympic Golden Rings Award Winners Unveiled in front of 1,000 Guests in Lausanne". IOC. 22 June 2019. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ "PyeongChang 2018 Launches Official Emblem". olympic.org. International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ^ "Olympics: 2018 Winter Olympics ... not in Pyongyang". The Manila Bulletin. Agence France-Presse. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Toyota's Olympic quest: How the automaker used Pyeongchang to rebrand". LA Biz. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "South Korean car companies could still sponsor Pyeongchang 2018 despite Toyota deal with IOC". Inside the Games. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Toyota makes up for low profile in PyeongChang with social media engagement". Sportcal. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Baker, Liana B. "Toyota leaves Pyeongchang podium to South Korean rivals". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Hyundai, Kia support PyeongChang with 4,100 vehicles, W50b donation". The Korea Herald. 8 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Lunden, Ingrid. "Intel and the IOC ink 7-year Olympics tech deal for VR, drones and more". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Fischer, Ben (12 February 2018). "On The Ground: Winter Games – IOC's New Tech Partners Collaborate, Compete At Same Time". Sports Business Daily. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ "South Korea's Moon says pushing to guarantee safety at Pyeongchang Olympics". Reuters. 20 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- ^ "France to skip 2018 Winter Games if security not assured". Reuters. 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Olympics: North Korea triggers 2018 Winter Olympics security scare". The Straits Times. 23 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017.

- ^ "US ambassador to UN says it's an 'open question' whether U.S. athletes will participate in Winter Olympics over safety concerns". Business Insider. 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Ellen (7 December 2017). "White House walks back remarks that US athletes might not participate in 2018 Olympics". The Hill. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Kim Jong Un highlights his 'nuclear button,' offers Olympic talks". NBC News. 2 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (8 January 2018). "North Korea to Send Olympic Athletes to South Korea, in Breakthrough". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "'The Pyongyang Olympics' – Backlash in South Korea over plans to march with North at Winter Olympics". The Telegraph. 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "South Korean protesters object to Olympic Games deal with North Korea". Los Angeles Times. 18 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Rap video frosty welcome for 2018 Winter Olympic Games". BBC News. 2 February 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Korean Olympic Cooperation Provokes Protests in Seoul". Time. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Haas, Benjamin (9 February 2018). "US vice-president skips Olympics dinner in snub to North Korea officials". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Uri. "North Korea's Undeserved Olympic Glory". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Labott, Elise (9 February 2018). "As North Koreans arrive at Olympics, Pence points to defectors to counter regime". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "US says North Korea cancelled planned meeting with US VP Mike Pence". Stuff (Fairfax). 21 February 2018. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ "North Korea's controversial Olympics delegate". BBC News. 23 February 2018. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (22 February 2018). "Former Spymaster to Lead North Korea's Olympic Ceremony Delegation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Ruiz, Rebecca C.; Panja, Tariq (5 December 2017). "Russia Banned From Winter Olympics by I.O.C." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "IOC's OAR implementation group releases guidelines for uniforms accessories and equipment's". olympic.org. 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017.

- ^ "IOC Statement on CAS Decision". International Olympic Committee. 1 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ "Putin says US pressured IOC to ban Russia from Winter Games". Yahoo Sports. Agence France-Presse. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Жириновский предложил отказаться от участия в Олимпиаде-2018" [Zhirinovsky offered to refuse to participate in the 2018 Olympics]. sport-interfax.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin won't tell Russian athletes to boycott Winter Olympics". CNN. 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Putin: Doping allegations 'US plot against Russian election'". BBC News. 9 November 2017. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ "Опрос "КП": Стоит ли спортсменам из России ехать на Олимпиаду под нейтральным флагом" [Poll "KP": Should athletes from Russia go to the Olympics under a neutral flag]. kp.ru (in Russian). 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Ortiz, Eirk (14 February 2018). "Russian fans spurn 'stupid' ban on athletes at Olympic Games". NBC News. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018.

- ^ "The 2018 Winter Olympics Are Already Tainted". The New York Times. 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ "IOC Chief Disappointed By Court Lifting Doping Ban On Russians". rferl.org. 4 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

External links[edit]

- "Pyeongchang 2018". Olympics.com. International Olympic Committee.

- Pyeongchang 2018 Archived 6 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- 2018 Winter Olympics

- 2018 in multi-sport events

- 2018 in South Korean sport

- 2018 in winter sports

- February 2018 sports events in South Korea

- Olympic Games in South Korea

- Sports competitions in Gangneung

- Sports competitions in Pyeongchang County

- Winter Olympics by year

- Winter sports competitions in South Korea