User:SuzuHigana/Rialto Bridge

Rialto Bridge Ponte di Rialto | |

|---|---|

The Rialto Bridge | |

| Coordinates | 45°26′17″N 12°20′10″E / 45.4380°N 12.3360°E |

| Carries | pedestrian bridge[1] |

| Crosses | Grand Canal |

| Locale | Venice, Veneto, Italy |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | stone arch bridge |

| Width | 22.90 metres (75.1 ft)[2] |

| Height | 7.32 metres (24.0 ft) (arch only) |

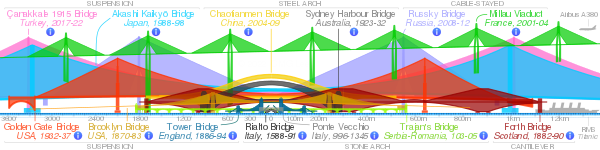

| Longest span | 31.80 metres (104.3 ft) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1588 |

| Construction end | 1591 |

| Location | |

| |

The Rialto Bridge (Italian: Ponte di Rialto; Venetian: Ponte de Rialto) is the oldest[3] of the four bridges spanning the Grand Canal in Venice, Italy, designed by Antonio da Ponte.[3] The name origin of Rialto is rivus praeltus, meaning "deep channel".[4] Connecting the sestieri (districts) of San Marco and San Polo, it has been rebuilt several times since its first construction as a pontoon bridge in 1173.[4] The Rialto Bridge is an object of art historical significance because it is depicted in different paintings throughout history.[3] A strong wooden foundation is used to reinforce the current stone bridge.[4]

Now, the bridge is lined with shops and is a significant tourist attraction in the city.[5]

History[edit]

Ponte Della Moneta, Pontoon Bridge (1181-1255)[edit]

This timber pontoon bridge was the first dry crossing of the Grand Canal, in the same location as the current Rialto Bridge.[4] Even before the pontoon bridge, there were several floating bridges made of boats and connected to each other with planks.[4] The floating boat bridges were in place before the last pontoon bridge was built by Nicolo Barattieri in 1181.[4] This bridge was built at the lowest bridging point, which is the most seaward position at which a bridge could easily be constructed.[3]

This pontoon bridge was known as the Ponte Della Moneta, which translates to "the coin bridge". It was presumably named after the Zecca of Venice, the mint that stood near its eastern end.[4]

Wooden Bridge (1255-1524)[edit]

The development and importance of the Rialto market on the eastern bank increased traffic on the pontoon bridge, so it was replaced in 1255 by a wooden bridge.[6] The first wooden bridge was a permanent wooden structure, also made of timber.[3] It was damaged in 1310 when conspirators of the insurrection against the government of the Serenissima, led by Bajamonte Tiepolo, lit the bridge on fire after their failed assault on the Palazzo Ducale.[4]This first wooden bridge collapsed under a crowd that came to spectate the visit of Emperor Frederick III of Austria in 1450.[3]

The second iteration of the wooden bridge had two inclined ramps meeting at a movable central section that could be raised to allow the passage of tall ships.[3] During the first half of the 15th century, two rows of shops were built along the sides of the bridge, similar to the Ponte Vecchio in Florence.[3] The connection with the Rialto market eventually led to a change of name for the bridge, from Ponte Della Moneta to Ponte di Rialto, or Rialto Bridge.[4] The rent from the shops brought an income to the State Treasury, which helped maintain the bridge. Another collapse occurred in 1524.[4]

Stone Bridge (1588-present)[edit]

The idea of rebuilding the bridge in stone was first proposed in 1503.[4] The first plan came from Fra Giovanni Giocondo in 1514, which also included renovations of the Rialto Market.[4] Several projects were considered over the following decades. In 1551, Venetian authorities called for a contract to rebuild the bridge. A special commission was appointed, consisting of three supervisors for the bridge and other buildings.[4] In 1554, several architects competed over the project. It was not until the end of the sixteenth century that the Doge Pasquale Cicogna launched a competition for the proposals of a new stone bridge.[4] Renowned architects such as Michelangelo[5], Jacopo Sansovino, Andrea Palladio, and Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola all submitted proposals.[3] However, their approaches all involved a Classical approach with several arches. This approach was judged inappropriate to the situation, since the arches did not allow for naval traffic below the bridge itself.[4] The competition re-opened in 1587, and both Vincenzo Scamozzi and Antonio da Ponte proposed designs for single-arch bridges.[4] Antonio da Ponte's proposal was finally selected as the final design for the bridge on June 9, 1588.[3] The building process was completed in 1591 with the help of Tommaso Contin da Besso.[4] In total, the bridge cost as much as 250,000 ducats to build.[3]

Until the 1850s, the Rialto Bridge was the only fixed dry crossing point for the Grand Canal.[3] The present single span stone bridge is similar to the wooden bridge it succeeded. Two inclined ramps lead up to a central portico. On either side of the portico, the covered ramps carry rows of shops. While critics have predicted the bridge to fail due to its single-arch design[7], The bridge has defied its critics to become one of the architectural icons of Venice.[5]

In Art and Architectural History[edit]

Bridge Reliefs[edit]

One set of the Reliefs on the Rialto Bridge, sculpted by Agostino Rubini, illustrates the scene of the Annunciation.[8] The Archangel Gabriel is positioned on the left side relative to the Virgin Annunciate. This appropriation of the Annunciation was one of the few monumental expressions of the story created in Venice before the 15th century.[8] These set of reliefs were significant because of their placement in Rialto. As the first Christian Church in Venice was established in Rialto, it was considered to be sacred civic ground.[8]

Representations[edit]

Miracle of the Relic of the cross at the Ponte di Rialto by Vittore Carpaccio (1494)[edit]

Main Article: Miracle of the Relic of the cross at the Ponte di Rialto

The painting depicts the wooden bridge that has been rebuilt after the collapse in 1450.[3] In addition to the wooden bridge, the painting also depicts richly-painted and marble-clad palaces lining the Grand Canal.[9]

View of Venice by Jacopo de Barbari (1500)[edit]

Main Article: View of Venice

This woodcut, designed by Jacopo de Barbari, was printed from six blocks and nine feet across. The print captured the Rialto market district and the wooden version of the Rialto Bridge.[8]

Capriccio View with Palladio's Design for the Rialto Bridge by Canaletto (1742)[edit]

Main Article: Canaletto

Canaletto's painting depicts a fictional Rialto Bridge according to Palladio's design. Palladio's design for the Rialto Bridge was rejected in the late 1560s. He published this design in 1570s and expressed his fondness for the bridge itself and its potential for business and trade.[10] Palladio re-designed the old wooden bridge to maximize the potential for trade,[10] it would have six rows of shops in three streets. In addition the the bridge itself, Palladio also considered renovating the entire Rialto area,[4] adding two commercial areas at the bridgeheads.[4] In addition to the bridge having multiple arches that did not allow naval traffic[4], the openings in the porticoes would be too narrow to accommodate the foot traffic.[10] Palladio's approach to the bridge was therefore considered impractical for the number of people using the bridge and the traders bringing goods over it.[10]

This painting is in a series of thirteen outdoor paintings with imaginary views by Canaletto.[10] Now, nine out of thirteen of these paintings are in the Royal Collection.[10]

Michele Marieschi (1710-1744)[edit]

Main Article: Michele Marieschi

Michele Marieschi depicted the Rialto Bridge with its stalls and embankments nearby as the trading and business center in the 18th-century Venice.[11]

Specifications[edit]

Wooden Foundations[edit]

The foundations of the Rialto Bridge were build on steps of three levels. It occupies an area around 700 square meters and uses approximately 6000 poles per side. In between the foundation piles, about 2000 piles made from wood other than timber are inserted to reinforce the foundation.[4]

Today[edit]

Today, the Bridge is one of the top tourism attractions in Venice.[12] It is considered the busiest bridge and the most important connection among the approximately 400 bridges in the city.[13]

Other names[edit]

It was called Shylock's bridge in Robert Browning's poem "A Toccata of Galuppi's".

See also[edit]

A Virtual Time Machine for Venice illustrates the development of the Rialto District.

References[edit]

- ^ Fulton, Charles Carroll (1874). Europe Viewed Through American Spectacles. Philadelphia: J.P. Lippincott & Co. p. 242. Retrieved 5 September 2008 – via Internet Archive.

There being no vehicles or horses in Venice, it is simply for pedestrians.

- ^ "Rialto Bridge". structurae.net. Archived from the original on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Howard, Deborah, 1946- (2002). The architectural history of Venice. Quill, Sarah. (Rev. and enl. ed. with new photographs / by Sarah Quill and Deborah Howard ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09029-3. OCLC 48876512.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Bernabei, Mauro; Macchioni, Nicola; Pizzo, Benedetto; Sozzi, Lorena; Lazzeri, Simona; Fiorentino, Luigi; Pecoraro, Elisa; Quarta, Gianluca; Calcagnile, Lucio. "The wooden foundations of Rialto Bridge (Ponte di Rialto) in Venice: Technological characterisation and dating". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 36: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2018.07.015.

- ^ a b c Dupré, Judith (2017). Bridges: A History of the World's Most Spectacular Spans. New York: Hachette/Black Dog & Leventhal Press. ISBN 978-0-316-47380-4.

- ^ Molmenti, Pompeo; Horatio Forbes Brown (13 October 1906). Venice: Its Individual Growth from the Earliest Beginnings to the Fall of the Republic. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co. p. 29. Retrieved 5 September 2008 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Rialto Bridge (Ponte di Rialto)". U.S. News Report.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d Rosand (book author), David; Romano (review author), Dennis (1 January 2002). "Myths of Venice: The Figuration of a State". Renaissance and Reformation. 38 (2): 106–107. doi:10.33137/rr.v38i2.8783. ISSN 2293-7374.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Humfrey, Peter, 1947- (1995). Painting in Renaissance Venice. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06247-8. OCLC 31132099.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Canaletto (Venice 1697-Venice 1768) - Capriccio View with Palladios Design for the Rialto Bridge". www.rct.uk. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- ^ "Rialto Bridge in Venice". The State Hermitage Museum.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Povoledo, Elisabetta (30 March 2017). "3 Are Held on Suspicion of Plot to Attack Rialto Bridge in Venice". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

The Italian police announced on Thursday that they had dismantled a suspected jihadist cell whose members had discussed blowing up the Rialto Bridge, one of the top tourist attractions in Venice

- ^ Russo, Salvatore. "Integrated assessment of monumental structures through ambient vibrations and ND tests: The case of Rialto Bridge". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 19: 402–414. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2016.01.008.