Swedish Sign Language family

| Swedish Sign Language family | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Europe, Africa |

| Linguistic classification | ? British Sign

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | swed1257 |

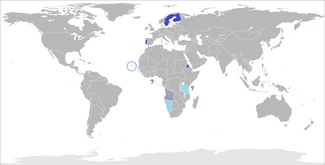

Part of the Swedish Sign Language family

Secondarily influenced by the Swedish Sign Language family | |

The Swedish Sign Language family is a language family of sign languages, including Swedish Sign Language, Portuguese Sign Language, Cape Verdian Sign Language, Finnish Sign Language and Eritrean Sign (although going through the process of demissionization).[1]

History[edit]

There is evidence of usage of signed languages in the Nordic countries from the 18th century, but the later 19th century political situation split the Nordic sign languages into two distinct language families, the Swedish Sign Language family and the Danish Sign Language family.[3]

Relation to other Families[edit]

Swedish SL started about 1800. Henri Wittmann proposes that it descends from British Sign Language. Regardless, Swedish SL in turn gave rise to Portuguese Sign Language (1823) and Finnish Sign Language (1850s), the latter with local admixture; Finnish and Swedish Sign are mutually unintelligible.[4]

Ethnologue reports that Danish Sign Language is largely mutually intelligible with Swedish Sign, though Wittmann places DSL in the French Sign Language family. There are no known dialects in the Swedish Sign Language, however, it is partly intelligible with other manual languages such as Danish (DSL), Norwegian (NSL), and Finnish (FSE).[5]

Although not directly related to the Guinea-Bissau Sign language, it has borrowed the alphabet from Portuguese sign.[6] Namibian Sign Language has also been influenced by Swedish Sign, because some deaf adults went into Sweden before becoming leaders in the deaf community in Namibia.[7]

It has also been reported that Tanzanian sign may have been influenced by Finnish and Swedish sign languages, although the evidence is not explicit.[8]

Nordic Branch[edit]

Swedish Sign Language is the sign language used in Sweden. It is recognized by the Swedish government as the country's official sign language, and hearing parents of deaf individuals are entitled to access state-sponsored classes that facilitate their learning of SSL.[9] Swedish sign language is strongly linked to the culture of Sweden. There are around 13.000 native speakers and a total of 30.000 speakers. [1]

Finnish Sign Language can be traced back to the mid-1800s when Carl Oscar Malm, a Finnish deaf individual who had studied in Sweden, founded Finland's first school for the deaf in Porvoo in 1846. The Swedish sign language used by Malm spread among Finnish deaf individuals, evolving into its own language. The first association for the deaf in Finland was established in Turku in 1886. Albert Tallroth was involved in founding five different deaf associations and also the Finnish Association of the Deaf. By the late 1800s, oralism, or the speech method, began to be favored in the education of the deaf in Finland. This led to the prohibition of sign language in schools, even under threat of punishment. And as a result of oralism, Finnish Sign Language and Finnish-Swedish Sign Language began to diverge. Despite the ban, students in deaf schools continued to use sign language secretly in dormitories. The use of sign language persisted within the deaf community, while spoken language learned in school was used when interacting with hearing individuals.[10]

The Finland-Swedish Sign Language, also known as FinSSL, was created by the deaf community of Swedish backgrounds inhabiting the coastal areas of Finland. It is declared as an independent language given the connection to the Finland-Swedish culture.[11] Since 2015, Finland-Swedish and Finnish sign languages have been recognized as separate languages in Finnish legislation, as the new sign language act was adopted in the parliament. However, the scientific consensus has been since 2005 that the two sign languages are distinct.[12] Through contacts between Swedish deaf individuals and Finland-Swedish deaf individuals, the Finland-Swedish sign language has borrowed many words from Swedish sign language. Additionally, the visual phonology with facial expressions follows the sounds of the Swedish language.[13][14]

Portuguese Branch[edit]

Portuguese Sign language (Portuguese: Língua gestual portuguesa) is a sign language used mainly by deaf people in Portugal. It is recognized in the present Constitution of Portugal.[15] It was significantly influenced by Swedish Sign Language, through a school for the Deaf that was established in Lisbon by Swedish educator Pär Aron Borg.[16][17] The Portuguese Sign Language has its origins from the Swedish Sign Language (LGS), as in the 19th century, the king called to Portugal Pär Aron Borg, a Swede who had founded an institute for the education of the deaf in Sweden. In 1823, the first school for the deaf was made in Portugal, and although the vocabulary of the Portuguese and Swedish sign languages have many differences from each other, the alphabet of the two languages shows their common origin.[18]

Cape Verdian Sign Language (Língua Gestual Caboverdiana)[19] is the sign language used by the deaf community in Cape Verde, numbering around 1500-4000. It is descended from Portuguese sign language and is mutually integible with it, although it contains some local adaptations.[20][21] In 2010, a school for children who are deaf was established in Cape Verde. Another deaf school was also established in Praia.[22]

Some reports have said that LGSTP is similar to Portuguese Sign and that much of it is mutually integible with Portuguese Sign.[23] Additionally, although not directly related to Portuguese Sign, the Guinea-Bissau Sign Language has borrowed the alphabet from Portuguese Sign. [24]

It is also reported that Portuguese Sign has been also used in Angola.[2]

Eritrean Sign[edit]

Eritrean Sign Language also developed out of the Swedish and Finnish Sign Languages,[25] that were introduced by Swedish and Finnish Christian missionaries in 1955,[25] containing a certain amount of local Eritrean signs and having ASL-based Sudanese influences.[26] According to Moges 2011, 70% of the EriSL and Finnish signs are identical.[25] Since 2005, the Eritrean National Association of the Deaf has made linguistic purification attempts to replace Swedish and Finnish signs from the EriSL lexicon by 'Eritrean' ones in an effort to create a more distinct, "indigenous" language.[25] This process is referred to as 'demissionization'.[1]

| Swedish Sign Language family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[edit]

- ^ a b Moges, Rezenet Tsegay (2015). It's a Small World. International Deaf Spaces and Encounters. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. pp. 114–125.

- ^ a b "Angola". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "Signed languages in the Nordic countries". nordics.info. 2022-02-16. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Wittmann, Henri (1991). "Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement" (PDF). Revue québécoise de linguistique théorique et appliquée (in French). 10 (1): 215–288. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Swedish Sign Language". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ^ "República da Guiné-Bissau (Republic of Guinea-Bissau)". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "Republic of Namibia". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "United Republic of Tanzania". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Haualand, Hilde; Holmström, Ingela (21 March 2019). "When language recognition and language shaming go hand in hand – sign language ideologies in Sweden and Norway". Deafness & Education International. 21 (2–3): 107. doi:10.1080/14643154.2018.1562636. hdl:10642/7861.

- ^ Salmi, Eeva; Laakso, Mikko (2005). "Helsingin kokous". Maahan lämpimään, Suomen viittomakielisten historia. Kuurojen Liitto ry. p. 152. ISBN 952-5396-30-4.

- ^ Jepsen, Julie (2015). Sign Languages of the World: a Comparative Handbook. De Gruyter.

- ^ "Finlandssvenskt teckenspråk och språkets revitalisering". Finlands Dövas Förbund (in Swedish). Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "Suomen viittomakielet". Kotimaisten kielten keskus (in Finnish). Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "Suomen kaksi viittomakieltä". Kielikello (in Finnish). 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ Constitution of Portugal, Article 71 and 74

- ^ Lucas, Ceil (2001). The Sociolinguistics of Sign Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780521794749. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Prawitz, J. "Pär Aron Borg - Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon". Svenskt biografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Retrieved 2022-03-16.

- ^ Pinto, Mariana Correia (2017-11-14). "O que todos devíamos saber sobre língua gestual (em dez pontos)". PÚBLICO (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ RTC. "Apresentado para validação, módulo formativo de língua gestual". My Application (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "Professoras da UFSM elaboram o primeiro dicionário de gestos voltado para a população surda de Cabo Verde". UFSM (in Brazilian Portuguese). 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "Cape Verde". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "Cape Verde". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ "Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "República da Guiné-Bissau (Republic of Guinea-Bissau)". African Sign Languages Resource Center. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ a b c d Moges, Rezenet Tsegay (2015). It's a Small World. International Deaf Spaces and Encounters. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. pp. 114–125.

- ^ Moges, Rezenet (January 2008). "Construction in Eritrean Sign Language". R. M. de Quadros (ed.). Editora Arara Azul. Petrópolis/RJ. Brazil. California State University. Retrieved 1 May 2013.