Solar eclipse of July 11, 1991

| Solar eclipse of July 11, 1991 | |

|---|---|

Totality from Playas del Coco, Costa Rica | |

| Type of eclipse | |

| Nature | Total |

| Gamma | −0.0041 |

| Magnitude | 1.08 |

| Maximum eclipse | |

| Duration | 413 s (6 min 53 s) |

| Coordinates | 22°00′N 105°12′W / 22°N 105.2°W |

| Max. width of band | 258 km (160 mi) |

| Times (UTC) | |

| (P1) Partial begin | 16:28:46 |

| (U1) Total begin | 17:21:41 |

| Greatest eclipse | 19:07:01 |

| (U4) Total end | 20:50:28 |

| (P4) Partial end | 21:43:24 |

| References | |

| Saros | 136 (36 of 71) |

| Catalog # (SE5000) | 9489 |

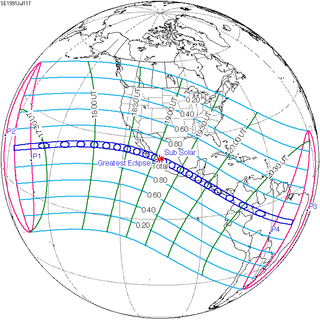

A total solar eclipse occurred at the Moon’s descending node of the orbit on Thursday, July 11, 1991. A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby totally or partly obscuring the image of the Sun for a viewer on Earth. A total solar eclipse occurs when the Moon's apparent diameter is larger than the Sun's, blocking all direct sunlight, turning day into darkness. Totality occurs in a narrow path across Earth's surface, with the partial solar eclipse visible over a surrounding region thousands of kilometres wide. Totality began over the Pacific Ocean and Hawaii moving across Mexico, down through Central America and across South America ending over Brazil. It lasted for 6 minutes and 53.08 seconds at the point of maximum eclipse. There will not be a longer total eclipse until June 13, 2132. This was the largest total solar eclipse of Solar Saros series 136, because eclipse magnitude was 1.07997.

This eclipse was the most central total eclipse in 800 years, with a gamma of -.0041. There will not be a more central eclipse for another 800 years. Its magnitude was also greater than any eclipse since the 6th century.

Observations[edit]

-

Animation of eclipse path

-

Partial phase before totality as seen through the cloud cover, Playas del Coco, Guanacaste, Costa Rica

An observation team funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China made near-infrared spectroscopic observations in the southern suburbs of La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico. Weather was clear on the eclipse day in La Paz. The team captured dozens of frames of the slitless spectrum of the upper layer of photosphere and chromosphere, and the slit spectrum outside the solar surface. They also captured images of the chromosphere and solar prominences. Among the professional observation teams from various countries to La Paz, six used the new CCD sensors for the first time in solar eclipse observation. Among them, the Chinese and Japanese team used it to observe long-wavelength spectra[1]. A team of 320 people from NASA's Johnson Space Center made observation in Mazatlán, Mexico. The local weather was not ideal in the days before the eclipse, but got slightly better as the eclipse day approached. Some people went to San Blas, Nayarit for better weather conditions. In the end, a hole in the clouds appeared in El Cid in western Mazatlan, through which the corona and prominences was visible. Other observers 1 to 5 miles away were clouded out. In San Blas, the corona and prominences were still visible, even though the clouds became thicker during totality[2]. Scientists from the Royal Observatory of Belgium, the Institute of Geodesy and Geophysics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Institute of Geophysics of the National Autonomous University of Mexico made observations in Mexico City to study the change in gravity during a total solar eclipse[3].

Related eclipses[edit]

Eclipses of 1991[edit]

- An annular solar eclipse on January 15.

- A penumbral lunar eclipse on January 30.

- A penumbral lunar eclipse on June 27.

- A total solar eclipse on July 11.

- A penumbral lunar eclipse on July 26.

- A partial lunar eclipse on December 21.

Alleged prediction[edit]

The American ethnographer and anthropologist Victoria Bricker and her late husband and colleague Harvey Bricker, claim in their book "Astronomy in the Maya Codices" that by decoding pre-Columbian glyphs from the four Maya codices they discovered that pre-16th century Mayan astronomers predicted the solar eclipse of July 11, 1991.[4] In their 2011 volume, the husband-wife Brickers team explain how they translated the dates from the Mayan calendar, then used modern scientific knowledge of planetary orbits to line up the data from the Mayan prediction with our calendar.[5] Reviewers disputed the claim in 2014, concluding that, "loose hieroglyphic readings and accommodating pattern matching occurs throughout the book."[6]

Notes[edit]

- ^ You Jianxi, Lu Jing, Wang Chuanjin, Lu Baoluo, Ming Changrong (July 1994). "1991年7月1日墨西哥日全食红外光谱观测及初步结果". 天体物理学报 (Journal of Astrophysics) (in Chinese). 14 (3): 277–282.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul D. Maley. "The Longest Total Solar Eclipse in Mexico – July 11, 1991". Archived from the original on 30 October 2020.

- ^ B. Ducarme, H.-P. Sun, N. d'Oreye, M. Van Ruymbeke, J. Mena Jara (1999). "Interpretation of the tidal residuals during the 11 July 1991 total solar eclipse". Journal of Geodesy. 73: 53–57. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Solar System, Exploration. "Eclipses". solarsystem.nasa.gov. Nasa. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Kramer, Miriam (January 8, 2013). "Ancient Maya Predicted 1991 Solar Eclipse". Live Science. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ Gerardo Aldana (March 2014). "ISIS: An International Review Devoted to the History of Science and to Cultural Influences". The University of Chicago Press Journals. 105 (1). doi:10.1086/676751. JSTOR 10.1086/676751. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

References[edit]

- NASA graphics

- Observer's handbook 1991, Editor Roy L. Bishop, The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (p. 101)

Photos:

- Russian scientist observed eclipse

- Russia expedition

- Baja California, La Paz. Prof. Druckmüller's eclipse photography site

- Baja California, Todos Santos. Prof. Druckmüller's eclipse photography site

- Reyna from La Paz, Baja California, Mexico

- www.noao.edu: Satellite view of eclipse

- [1] APOD 7/16/1999, Solar Surfin', total eclipse corona, from Mauna Kea, Hawaii

- [2] APOD 10/24/1995, A Total Solar Eclipse, total eclipse corona

- The 1991 Eclipse in Mexico

Videos:

- Total Solar Eclipse -- July 11, 1991 (9:39 uncut, eclipse full frame, location insert)

- Total Solar Eclipse (8:23 edited, includes pre-planning and post-press, music only)

- Total Solar Eclipse, Cabo Mexico (9:12 edited, includes some TV news coverage)