James White (inventor)

James White | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1762 Cirencester, England |

| Died | December 17, 1825 (aged 62–63) Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England |

| Occupations |

|

James White (1762 – December 17, 1825) was an English civil engineer and inventor. Born in Cirencester, he held an intense interest in mechanics at a young age. Moving to London in the 1780s, he created and patented various inventions, including a differential gear train and a model harbor crane. He moved to Paris in 1792, shortly following the French Revolution, and continued work in designing industrial machinery. Inventions from his period in Paris include an articulated barge, an early out-flow radial turbine, and an automatic wire nail-making machine. He presented a hypocycloidal straight-line mechanism at the 1801 Exposition des produits de l'industrie française at the Louvre, and was awarded a medal by Napoleon Bonaparte. He returned to England following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, and settled in the industrial and manufacturing center of Manchester. He published A New Century of Inventions in 1822, describing in detail over a hundred of his mechanisms from across his career. Notable inventions contained within the work include the earliest known design for a key-driven mechanical calculator. In late 1825, he died at his home in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester.

Biography[edit]

Early life and career[edit]

James White was born in Cirencester, Gloucestershire in 1762. No baptismal record exists of his birth, possibly indicating that his parents were Nonconformists. His interests in mechanics began at a young age; he claimed to have invented a mousetrap around age eight, and that he "became a tolerable workman in all the mechanical branches long before the age that boys are apprenticed to any."[1] Nothing is known of his education or whether he received an apprenticeship, although trade apprenticeships were limited in the mainly agrarian Cirencester.[1]

His first major invention, a "perpetual wedge machine" (a concentric wheel and axle with 100 and 99 teeth respectively) was produced in 1786. In 1788, while living in Holborn, London, he filed a patent for multiple devices. This included multiple mechanical devices he did not invent, such as the Chinese windlass. He received a 40 guinea prize for submitting a model of a harbor crane design to the Society of Arts.[1] At some point within the late 1780s, he built a differential gear train to change the gap between the millstones of a Kent windmill in order to account for varying wind speed. This was the first known industrial application of a differential,[2] although it is unknown if White was aware of its separate invention by clockmakers, first attested by Joseph Williamson c. 1720.[3] In early 1792, he sent a letter from the Chevening estate in Kent, possibly indicating his acquaintanceship with the scientifically-minded 3rd Earl Stanhope, whom he would later name his "noble Patron".[1]

France[edit]

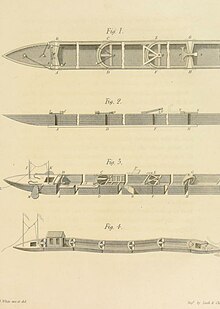

In 1792, he moved to Paris, and resided along the Quai de Bethune on the Île Saint-Louis. It is unknown why White moved to France during the ongoing French Revolution.[4][5] He patented a "serpentine boat" in 1795, articulating together a number of barges for transport in narrow or restrictive waterways, such as canals. He claimed to have invented a micrometer design later attributed to Gaspard de Prony, whom he showed the invention in 1796. He showcased a hypocycloidal straight-line mechanism at the 2nd Exposition des produits de l'industrie française in 1801, which he had designed in the years prior to the event. For this invention, White received a medal from First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte.[5] The following year, bolstered by cross-Channel transmission of information during the Peace of Amiens, Matthew Murray built a number of steam engines incorporating White's mechanism.[5][6]

In 1806, he invented a "horizontal waterwheel", taking the form of an out-flow radial turbine, predating a similar turbine by Benoît Fourneyron in the late 1820s. It is unknown if the two are connected. In 1808, he patented single and double helical gears, oriented at a 15° angle, described by a later biographer as "perhaps the invention on which he placed most store."[7] During the early 1810s, he took out a number of additional industrial patents in France, but was prevented from filing patents in Britain due to the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars. These inventions include an automatic nail-making machine (the first known device to produce wire nails) and shears for cutting circular portions out of sheet iron.[8]

Return to England and death[edit]

In 1815, following the Hundred Days and the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, White returned to England.[4][8] Upon his return, he moved to Manchester, then a major engineering and industrial center. In late 1815, he submitted a paper titled "On a new system of cog or toothed wheels" to the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester.[9] He died at his residence in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester on December 17, 1825.[10]

A New Century of Inventions[edit]

While in Manchester, White composed his main work, A New Century of Inventions, Being Designs and Descriptions of One Hundred Machines, Relating to Arts, Manufactures, and Domestic Life. Two editions, both dated 1822, were published in Manchester by Leech and Cheetham.[11] The work proliferated widely, reaching over 600 subscribers across the United Kingdom.[4][12]

Among the machines featured in the book is an early key-driven adding machine. It is unknown if a prototype of the design was ever constructed, but it would have predated the earliest known key-driven mechanical calculators (an 1834 design by Luigi Torchi) by over a decade. The device features a sliding wheel, used as a floating-point mechanism that can be manipulated to store powers of ten. Special wheels could be swapped in to add in other bases and units, such as one designed for adding £sd.[11]

-

Plate 12, showing a "dropping-weight mover" (Fig. 4.), his perpetual wedge machine (Fig. 5), an evaporator (Fig. 6), a grating machine (Fig. 7), a reduced-friction screw (Fig. 8–10, 12), and a micrometer (Fig. 11)

-

Plate 30, showing a calico printer "forcing machine" (Fig. 1–2) and a tallow cutter and processor (Fig. 3–6)

-

Plate 31, showing a washing machine for hospitals (Fig. 1–2), a land-based steam engine for boats in canals (Fig. 3–4), and a device for operating steam engine slide valves (Fig. 5–6)

-

Plate 32, showing a cutting machine

-

Plate 37, showing a printing machine (Fig. 1–2) and a "Machine for clearing turbid Liquors" (Fig. 3–4)

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d Dickinson 1951, p. 175.

- ^ Jeremy 1981, p. 217.

- ^ Jeremy 1981, pp. 217–222.

- ^ a b c White 1989, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Dickinson 1951, p. 176.

- ^ White 1988, p. 33.

- ^ Dickinson 1951, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b Dickinson 1951, p. 177.

- ^ Dickinson 1951, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Dickinson 1951, p. 178.

- ^ a b Roegel 2016, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Jeremy 1981, p. 224.

Bibliography[edit]

- Roegel, Denis (2016). "Before Torchi and Schwilgué, There Was White". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 38 (4). doi:10.1109/MAHC.2016.46.

- White, G. (1989). "Early Epicyclic Reduction Gears". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 24 (2). doi:10.1016/0094-114x(89)90020-7.

- White, G. (1988). "Epicyclic Gears Applied to Early Steam Engines". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 23 (1). doi:10.1016/0094-114x(88)90006-7.

- Jeremy, D. J. (1981). "Technological Diffusion: The Case of the Differential Gear". Industrial Archaeology Review. 5 (3). doi:10.1179/iar.1981.5.3.217.

- Dickinson, H.W. (1951). "James White and his "New Century of Inventions"". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 27 (1). doi:10.1179/tns.1949.016.