Thomas Chatterton

Thomas Chatterton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 November 1752[1] Bristol, England |

| Died | 24 August 1770 (aged 17) Holborn, London, England |

| Pen name | Thomas Rowley, Decimus |

| Occupation | Poet, forger |

Thomas Chatterton (20 November 1752 – 24 August 1770) was an English poet whose precocious talents ended in suicide at age 17. He was an influence on Romantic artists of the period such as Shelley, Keats, Wordsworth and Coleridge.

Although fatherless and raised in poverty, Chatterton was an exceptionally studious child, publishing mature work by the age of 11. He was able to pass off his work as that of an imaginary 15th-century poet called Thomas Rowley, chiefly because few people at the time were familiar with medieval poetry, though he was denounced by Horace Walpole.

At 17, he sought outlets for his political writings in London, having impressed the Lord Mayor, William Beckford, and the radical leader John Wilkes, but his earnings were not enough to keep him, and he poisoned himself in despair. His unusual life and death attracted much interest among the romantic poets, and Alfred de Vigny wrote a play about him that is still performed today. The oil painting The Death of Chatterton by Pre-Raphaelite artist Henry Wallis has enjoyed lasting fame.

Childhood[edit]

Chatterton was born in Bristol where the office of sexton of St Mary Redcliffe had long been held by the Chatterton family.[2] The poet's father, also named Thomas Chatterton, was a musician, a poet, a numismatist, and a dabbler in the occult. He had been a sub-chanter at Bristol Cathedral and master of the Pyle Street free school, near Redcliffe church.[3]

After Chatterton's birth (15 weeks after his father's death on 7 August 1752),[1] his mother established a girls' school and took in sewing and ornamental needlework. Chatterton was admitted to Edward Colston's Charity, a Bristol charity school, in which the curriculum was limited to reading, writing, arithmetic and the catechism.[3]

Chatterton, however, was always fascinated with his uncle the sexton and the church of St Mary Redcliffe. The knights, ecclesiastics and civic dignitaries on its altar tombs became familiar to him. Then he found a fresh interest in oaken chests in the muniment room over the porch on the north side of the nave, where parchment deeds, old as the Wars of the Roses, lay forgotten. Chatterton learned his first letters from the illuminated capitals of an old musical folio, and he learned to read out of a black-letter Bible. His sister said he did not like reading out of small books. Wayward from his earliest years, and uninterested in the games of other children, he was thought to be educationally backward. His sister related that on being asked what device he would like painted on a bowl that was to be his, he replied, "Paint me an angel, with wings, and a trumpet, to trumpet my name over the world."[4][3]

From his earliest years, he was liable to fits of abstraction, sitting for hours in what seemed like a trance, or crying for no reason. His lonely circumstances helped foster his natural reserve, and to create the love of mystery which exercised such an influence on the development of his poetry. When Chatterton was age 6, his mother began to recognise his capacity; at age 8, he was so eager for books that he would read and write all day long if undisturbed; by the age of 11, he had become a contributor to Felix Farley's Bristol Journal.[3]

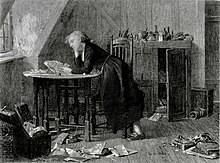

His confirmation inspired him to write some religious poems published in that paper. In 1763, a cross which had adorned the churchyard of St Mary Redcliffe for upwards of three centuries was destroyed by a churchwarden. The spirit of veneration was strong in Chatterton, and he sent to the local journal on 7 January 1764 a satire on the parish vandal. He also liked to lock himself in a little attic which he had appropriated as his study; and there, with books, cherished parchments, loot purloined from the muniment room of St Mary Redcliffe, and drawing materials, the child lived in thought with his 15th-century heroes and heroines.[3]

First "medieval" works[edit]

The first of his literary mysteries was the dialogue of "Elinoure and Juga," which he showed to Thomas Phillips, the usher at Colston's Hospital (where he was a pupil), pretending it was the work of a 15th-century poet. Chatterton remained a boarder at Colston's Hospital for more than six years, and it was only his uncle who encouraged the pupils to write. Three of Chatterton's companions are named as youths whom Phillips's taste for poetry stimulated to rivalry; but Chatterton told no one about his own more daring literary adventures. His little pocket-money was spent on borrowing books from a circulating library; and he ingratiated himself with book collectors, in order to obtain access to John Weever, William Dugdale and Arthur Collins, as well as to Thomas Speght's edition of Chaucer, Spenser and other books.[3] At some point he came across Elizabeth Cooper's anthology of verse, which is said to have been a major source for his inventions.[5]

Chatterton's "Rowleian" jargon appears to have been chiefly the result of the study of John Kersey's Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, and it seems his knowledge even of Chaucer was very slight. His holidays were mostly spent at his mother's house, and much of them in the favourite retreat of his attic study there. He lived for the most part in an ideal world of his own, in the reign of Edward IV, during the mid-15th century, when the great Bristol merchant William II Canynges (died 1474), five times mayor of Bristol, patron and rebuilder of St Mary Redcliffe "still ruled in Bristol's civic chair." Canynges was familiar to him from his recumbent effigy in Redcliffe church, and is represented by Chatterton as an enlightened patron of art and literature.[6]

Adopts persona of Thomas Rowley[edit]

Chatterton soon conceived the romance of Thomas Rowley, an imaginary monk of the 15th century,[3] and adopted for himself the pseudonym Thomas Rowley for poetry and history. According to psychoanalyst Louise J. Kaplan, his being fatherless played a great role in his imposturous creation of Rowley.[7] The development of his masculine identity was held back by the fact that he was raised by two women: his mother Sarah and his sister Mary. Therefore, "to reconstitute the lost father in fantasy,"[8] he unconsciously created "two interweaving family romances [fantasies], each with its own scenario."[9] The first of these was the romance of Rowley for whom he created a fatherlike, wealthy patron, William Canynge, while the second was as Kaplan named it his romance of "Jack and the Beanstalk." He imagined he would become a famous poet who by his talents would be able to rescue his mother from poverty.[10]

At the same time, there was a real poet named Thomas Rowley in Vermont, although it is unlikely that Chatterton was aware of the existence of the American poet.[citation needed]

Chatterton's search for a patron[edit]

To bring his hopes to life, Chatterton started to look for a patron. At first, he was trying to do so in Bristol where he became acquainted with William Barrett, George Catcott and Henry Burgum. He assisted them by providing Rowley transcripts for their work. The antiquary William Barrett relied exclusively on these fake transcripts when writing his History and Antiquities of Bristol (1789) which became an enormous failure.[11] But since his Bristol patrons were not willing to pay him enough, he turned to the wealthier Horace Walpole.[12] In 1769, Chatterton sent specimens of Rowley's poetry and "The Ryse of Peyncteynge yn Englade"[13] to Walpole who offered to print them "if they have never been printed."[14] Later, however, finding that Chatterton was only 16 and that the alleged Rowley pieces might have been forgeries, he scornfully sent him away.[15]

Political writings[edit]

Badly hurt by Walpole's snub, Chatterton wrote very little for a summer. [when?] Then, after the end of the summer, he turned his attention to periodical literature and politics, and exchanged Farley's Bristol Journal for the Town and Country Magazine and other London periodicals. Imitating the style of the pseudonymous letter writer Junius, then in the full blaze of his triumph, he turned his pen against the Duke of Grafton, the Earl of Bute and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (the then Princess of Wales).[16]

Leaving Bristol[edit]

He had just dispatched one of his political diatribes to the Middlesex Journal when he sat down on Easter Eve, 17 April 1770, and penned his "Last Will and Testament," a satirical compound of jest and earnest, in which he intimated his intention of ending his life the following evening. Among his satirical bequests, such as his "humility" to the Rev. Mr Camplin, his "religion" to Dean Barton, and his "modesty" along with his "prosody and grammar" to Mr Burgum, he leaves "to Bristol all his spirit and disinterestedness, parcels of goods unknown on its quay since the days of Canynge and Rowley."[17] In more genuine earnestness, he recalls the name of Michael Clayfield, a friend to whom he owed intelligent sympathy. The will was possibly prepared in order to frighten his master into letting him go. If so, it had the desired effect. John Lambert, the attorney to whom he was apprenticed, cancelled his indentures; his friends and acquaintances having donated money, Chatterton went to London.[16]

London[edit]

Chatterton already was known to the readers of the Middlesex Journal as a rival of Junius under the nom de plume of Decimus. He also had been a contributor to Hamilton's Town and Country Magazine, and speedily found access to the Freeholder's Magazine, another political miscellany supportive of John Wilkes and liberty. His contributions were accepted, but the editors paid little or nothing for them.[16]

He wrote hopefully to his mother and sister, and spent his first earnings in buying gifts for them. Wilkes had noted his trenchant style "and expressed a desire to know the author";[18] and Lord Mayor William Beckford graciously acknowledged a political address of his, and greeted him "as politely as a citizen could."[19]

Chatterton was abstemious and extraordinarily diligent. He could assume the style of Junius or Tobias Smollett, reproduce the satiric bitterness of Charles Churchill, parody James Macpherson's Ossian, or write in the manner of Alexander Pope or with the polished grace of Thomas Gray and William Collins.[16]

He wrote political letters, eclogues, lyrics, operas and satires, both in prose and verse. In June 1770, after nine weeks in London, he moved from Shoreditch, where he had lodged with a relative, to an attic in Brook Street, Holborn (now beneath Alfred Waterhouse's Holborn Bars building). He was still short of money; and now, state prosecutions of the press rendered letters in the Junius vein no longer admissible. This threw him back on the lighter resources of his pen. In Shoreditch, he had shared a room; but now, for the first time, he enjoyed uninterrupted solitude. His bed-fellow at Mr Walmsley's, Shoreditch, noted that much of the night was spent by him in writing; and now he could write all throughout the night. The romance of his earlier years re-emerged, and he transcribed from an imaginary parchment of the old priest Rowley his "Excelente Balade of Charitie." This poem, disguised in archaic language, he sent to the editor of the Town and Country Magazine, where it was rejected.[16][20]

Mr Cross, a neighbouring apothecary, repeatedly invited him to join him at dinner or supper; but he refused. His landlady, too, pressed him to share her dinner, but in vain. "She knew," as she afterwards said, "that he had not eaten anything for two or three days."[21] However, Chatterton assured her that he was not hungry. The note of his actual receipts, found in his pocket-book after his death, shows that Hamilton, Fell and other editors who had been so liberal in flattery, had paid him at the rate of a shilling for an article, and less than eightpence each for his songs; much of the accepted material was held in reserve and still unpaid for. According to his foster-mother, Chatterton had wished to study medicine with Barrett, and in his desperation he wrote to Barrett for a letter to help him to an opening as a surgeon's assistant on board an African trading ship.[16]

Death[edit]

In August 1770, while walking in St Pancras Churchyard, Chatterton was much absorbed in thought, and did not notice a newly dug open grave in his path, and tumbled into it. On observing this event, his walking companion helped Chatterton out of the grave, and told him in a jocular manner that he was happy in assisting at the resurrection of genius. Chatterton replied, "My dear friend, I have been at war with the grave for some time now." Chatterton committed suicide three days later.[22] On 24 August 1770, he retired for the last time to his attic in Brook Street, carrying with him arsenic,[23] which he drank after tearing into fragments whatever literary remains were at hand. He was 17 years and nine months old.[16] There has been some speculation that Chatterton may have taken the arsenic as a treatment for a venereal disease,[24] as it was commonly used for such at that time.[25]

A few days later, one Dr Thomas Fry came to London with the intention of giving financial support to the young boy "whether discoverer or author merely."[26] A fragment, probably one of the last pieces written by the poet, was put together by Dr Fry from the shreds of paper that covered the floor of Chatterton's attic on the morning of 25 August 1770. The would-be patron of the poet had an eye for literary forgeries, and purchased the scraps that the poet's landlady, Mrs Angel, swept into a box, cherishing the hope of discovering a suicide note among the pieces.[27] This fragment, possibly one of the remnants of Chatterton's very last literary efforts, was identified by Dr Fry to be a modified ending of the poet's tragical interlude Aella.[28] The fragment is now in the possession of Bristol Public Library and Art Gallery.

Coernyke.

Awake! Awake! O Birtha, swotie[a] mayde!

Thie Aella deadde, botte thou ynne wayne wouldst dye,

Sythence[b] he thee for renomme[c] hath betrayde,

Bie hys owne sworde forslagen[d] doth he lye;

Yblente[e] he was to see thie boolie[f] eyne,

Yet nowe o Birtha, praie, for Welkynnes,[g] lynge![h]

How redde thie lippes, how dolce[i] thie deft[j] cryne,[k]

.......................................scalle[l] bee thie Kynge!

.......................................a.

...........................................omme the kiste[m]

................................................................[29]

The final Alexandrine is completely missing, together with Chatterton's notes. However, according to Dr Fry, the character who utters the final lines must have been Birtha,[30] whose last word might have been something like "kisste".[31][32]

Posthumous recognition[edit]

The death of Chatterton attracted little notice at the time; for the few who then entertained any appreciative estimate of the Rowley poems regarded him as their mere transcriber. He was interred in a burying-ground attached to the Shoe Lane Workhouse in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, later the site of Farringdon Market. There is a discredited story that the body of the poet was recovered, and secretly buried by his uncle, Richard Phillips, in Redcliffe Churchyard. There a monument has been erected to his memory, with the appropriate inscription, borrowed from his "Will", and so supplied by the poet's own pen. "To the memory of Thomas Chatterton. Reader! judge not. If thou art a Christian, believe that he shall be judged by a Superior Power. To that Power only is he now answerable."[16]

It was after Chatterton's death that the controversy over his work began. Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century (1777) was edited by Thomas Tyrwhitt, a Chaucerian scholar who believed them genuine medieval works. However, the appendix to the following year's edition recognises that they were probably Chatterton's own work. Thomas Warton, in his History of English Poetry (1778) included Rowley among 15th-century poets, but apparently did not believe in the antiquity of the poems. In 1782 a new edition of Rowley's poems appeared, with a "Commentary, in which the antiquity of them is considered and defended," by Jeremiah Milles, Dean of Exeter.[16]

The controversy which raged round the Rowley poems is discussed in Andrew Kippis, Biographia Britannica (vol. iv., 1789), where there is a detailed account by George Gregory of Chatterton's life (pp. 573–619). This was reprinted in the edition (1803) of Chatterton's Works by Robert Southey and Joseph Cottle, published for the benefit of the poet's sister. The neglected condition of the study of earlier English in the 18th century alone accounts for the temporary success of Chatterton's mystification. It has long been agreed that Chatterton was solely responsible for the Rowley poems; the language and style were analysed in confirmation of this view by W. W. Skeat in an introductory essay prefaced to vol. ii. of The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton (1871) in the "Aldine Edition of the British Poets." The Chatterton manuscripts originally in the possession of William Barrett of Bristol were left by his heir to the British Museum in 1800. Others are preserved in the Bristol library.[33]

Legacy[edit]

Chatterton's genius and his death are commemorated by Percy Bysshe Shelley in Adonais (though its main emphasis is the commemoration of Keats), by William Wordsworth in "Resolution and Independence", by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in "Monody on the Death of Chatterton", by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in "Five English Poets", and in John Keats' sonnet "To Chatterton". Keats also inscribed Endymion "to the memory of Thomas Chatterton". Two of Alfred de Vigny's works, Stello and the drama Chatterton, give fictionalized accounts of the poet; in the former, there is a scene in which William Beckford's harsh criticism of Chatterton's work drives the poet to suicide. The three-act play Chatterton was first performed at the Théâtre-Français, Paris on 12 February 1835. Herbert Croft, in his Love and Madness, interpolated a long and valuable account of Chatterton, giving many of the poet's letters, and much information obtained from his family and friends (pp. 125–244, letter li.).[34]

The most famous image of Chatterton in the 19th century[citation needed] was The Death of Chatterton (1856) by Henry Wallis, now in Tate Britain, London. Two smaller versions, sketches or replicas, are held by the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art. The figure of the poet was modeled by the young George Meredith.[35]

Two of Chatterton's poems were set to music as glees by the English composer John Wall Callcott. These include separate settings of distinct verses within the Song to Aelle.[36] His best known poem, O synge untoe mie roundelaie was set to a five-part madrigal by Samuel Wesley.[37] Chatterton has attracted operatic treatment a number of times throughout history, notably Ruggero Leoncavallo's largely unsuccessful two-act Chatterton;[38] the German composer Matthias Pintscher's modernistic Thomas Chatterton (1998);[39] and Australian composer Matthew Dewey's lyrical yet dramatically intricate one-man mythography entitled The Death of Thomas Chatterton.[40]

There is a collection of "Chattertoniana" in the British Library, consisting of works by Chatterton, newspaper cuttings, articles dealing with the Rowley controversy and other subjects, with manuscript notes by Joseph Haslewood, and several autograph letters.[34] E. H. W. Meyerstein, who worked for many years in the manuscript room of the British Museum wrote a definitive work—"A Life of Thomas Chatterton"—in 1930.[41] Peter Ackroyd's 1987 novel Chatterton was a literary re-telling of the poet's story, giving emphasis to the philosophical and spiritual implications of forgery. In Ackroyd's version, Chatterton's death was accidental.[citation needed]

In 1886, architect Herbert Horne and Oscar Wilde unsuccessfully attempted to have a plaque erected at Colston's School, Bristol. Wilde, who lectured on Chatterton at this time, suggested the inscription: "To the Memory of Thomas Chatterton, One of England's Greatest Poets, and Sometime pupil at this school."[42]

In 1928, a plaque in memory of Chatterton was mounted on 39, Brooke Street, Holborn, bearing the inscription below.[43] The plaque has been since transferred to a modern office building on the same site.[44]

In a House on this Site

Thomas

Chatterton,

died

24 August 1770.

Within Bromley Common, there is a road called Chatterton Road; this is the main thoroughfare in Chatterton Village, based around the public house named The Chatterton Arms. Both road and pub are named after the poet.[45]

French singer Serge Gainsbourg entitled one of his songs Chatterton (1967), stating:[46]

Chatterton suicidé

Hannibal suicidé [...]

Quant à moi

Ça ne va plus très bien.

The song was covered (in Portuguese) by Seu Jorge live and recorded in the album Ana & Jorge: Ao Vivo.[47]

It was also recorded as an English language translation by Mick Harvey on the album "Intoxicated Man".[48]

French singer, songwriter and actor Alain Bashung entitled his 1994 studio album Chatterton .

French pop/rock band Feu! Chatterton took their name in homage to Chatterton. The band added the expression "Feu" ("fire", in French, formula once used for Kings' or Queens' death) to which they added an exclamation mark as a sign of resurrection.[49]

Works[edit]

- 'An Elegy on the much lamented Death of William Beckford, Esq.,' 4to, pp. 14, 1770.

- 'The Execution of Sir Charles Bawdwin' (edited by Thomas Eagles, F.S.A.), 4to, pp. 26, 1772.

- 'Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol, by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century' (edited by Thomas Tyrwhitt), 8vo, pp. 307, 1777.

- 'Appendix' (to the 3rd edition of the poems, edited by the same), 8vo, pp. 309–333, 1778.

- 'Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, by Thomas Chatterton, the supposed author of the Poems published under the names of Rowley, Canning, &c.' (edited by John Broughton), 8vo, pp. 245, 1778.

- 'Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol in the Fifteenth Century by Thomas Rowley, Priest, &c., [edited] by Jeremiah Milles, D.D., Dean of Exeter,' 4to, pp. 545, 1782.

- 'A Supplement to the Miscellanies of Thomas Chatterton,' 8vo, pp. 88, 1784.

- 'Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others in the Fifteenth Century' (edited by Lancelot Sharpe), 8vo, pp. xxix, 329, 1794.

- 'The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton,' Anderson s 'British Poets,' xi. 297–322, 1795.

- 'The Revenge: a Burletta; with additional Songs, by Thomas Chatterton,' 8vo, pp. 47, 1795.

- 'The Works of Thomas Chatterton' (edited by Robert Southey and Joseph Cottle), 3 vols. 8yo, 1803.

- 'The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton' (edited by Charles B. Willcox), 2 vols. 12mo, 1842.

- 'The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton' (edited by the Rev Walter Skeat, M.A.), Aldine edition, 2 vols. 8vo, 1876.

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Wikisource. Retrieved 14 March 2014

- ^ Basil Cottle, Thomas Chatterton (Bristol Historical Association pamphlets, no. 6, 1963), pp. 1-2

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm 1911, p. 10.

- ^ Kaplan 22

- ^ Yvonne Noble, "Cooper, Elizabeth (b. in or before 1698, d. 1761?)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 accessed 11 Nov 2014

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Kaplan 21

- ^ Kaplan 100

- ^ Kaplan 25

- ^ Kaplan 23

- ^ Kaplan 247

- ^ Kaplan 90

- ^ Meyerstein 254–5

- ^ Walpole's letter to Chatterton dated 28 March 1769 quoted in Meyerstein, 256–7

- ^ Meyerstein 262

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chisholm 1911, p. 12.

- ^ Chatterton's Last Will and Testament quoted in Meyerstein 342

- ^ Chatterton's letter to his mother dated 6 May 1770 quoted in Meyerstein 360

- ^ Chatterton's letter to his sister dated 30 May 1770 quoted in Meyerstein 372

- ^ Kaplan 173

- ^ quoted in Kroese 559

- ^ Clinch, George (1890). Marylebone and St. Pancras; their history, celebrities, buildings, and institutions. London: Truslove & Shirley. pp. 136–137. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "Thomas Chatterton". Poets' Graves. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Demetriou, Danielle (26 August 2004). "Reports of 18th century Romantic icon's suicide were 'greatly exaggerated'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "History of Sexually Transmitted Disease". 8 February 2010.

- ^ Meyerstein 450

- ^ Meyerstein 452

- ^ Meyerstein 452

- ^ quoted in Meyerstein 452

- ^ Meyerstein 452–3

- ^ 'kissed'

- ^ Meyerstein 453

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911, p. 13.

- ^ Tate. "'Chatterton', Henry Wallis, 1856". Tate Britain. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Rubin, Emanuel (2003). The English Glee in the Reign of George III: Participatory Art Music for an Urban Society. Harmonie Park Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-89990-116-9.

- ^ Kassler, Michael (5 July 2017). Samuel Wesley (1766–1837): A Source Book. Routledge. p. 613. ISBN 978-1-351-55012-3.

- ^ Kaminski, Piotr, 1001 opéras, Fayard, 2003, ISBN 978-8-32240-971-8, pp. 779–780 (in French)

- ^ Clements, Andrew (29 August 2003). "Matthias Pintscher, the radical conservative". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "The death of Chatterton : a mythography in one act for one man". Australian Music Centre. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Baker, Ernest A. (October 1931). "[Untitled]". The Modern Language Review. 26 (4): 474. doi:10.2307/3715537. JSTOR 3715537.

- ^ Hart-Davis, Rupert ed. Selected Letters of Oscar Wilde Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979. pp. 66–67.

- ^ Wright, GW. The London memorial to Thomas Chatterton, Notes and Queries, 15 December 1928, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Google Streetview, 39 Brooke St, Camden Town, Greater London EC1N

- ^ "Chatterton Village, Bromley Common – 08 March 2011 – Guide2Bromley News". Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ "Chatterton". lyrics.com. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Ana & Jorge: Ao Vivo at AllMusic

- ^ Intoxicated Man at AllMusic

- ^ "Feu! Chatterton : «Nos chansons sont un exutoire pour notre mélancolie»". LEFIGARO (in French). 1 December 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Attribution[edit]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chatterton, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–13.

- Kent, William Charles Mark (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 10. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 143–154.

Bibliography[edit]

- Cook, Daniel. Thomas Chatterton and Neglected Genius, 1760–1830. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Cottle, Basil. Thomas Chatterton (Bristol Historical Association pamphlets, no. 6, 1963), 15 pp.

- Croft, Sir Herbert. Love and Madness. London: G Kearsly, 1780. <https://books.google.com/books?id=hDImAAAAMAAJ>

- Heys, Alistair ed. From Gothic to Romantic: Thomas Chatterton's Bristol. Bristol: Redcliffe, 2005.

- Haywood, Ian. The making of history: a study of the literary forgeries of James Macpherson and Thomas Chatterton in relation to eighteenth-century ideas of history and fiction. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, c1986.

- Kaplan, Louise J. The Family Romance of the Impostor-poet Thomas Chatterton. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989. <https://books.google.com/books?id=EZGHZv8-0bYC>

- Kroese, Irvin B.. "Chatterton's Aella and Chatterton." SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. XII.3 (1972):557-66. JSTOR 449952

- Meyerstein, Edward Harry William. A Life of Thomas Chatterton. London: Ingpen and Grant, 1930.

- Groom, Nick ed. Thomas Chatterton and romantic culture. London: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

- Groom, Nick. "Chatterton, Thomas (1752–1770)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5189. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Thomas Chatterton at the Eighteenth-Century Poetry Archive (ECPA)

- Works by Thomas Chatterton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Chatterton at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Chatterton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Thomas Chatterton at Find a Grave

- The Rowley Poems at Exclassics.com

- Musical settings of Chatterton's poems

- Thomas Chatterton papers. Between 1758 and 1770. 2 items. At the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.