The Tin Drum

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

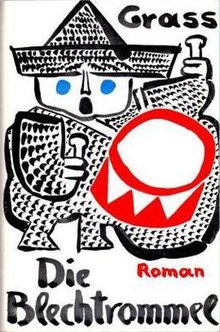

Cover of the first German edition | |

| Author | Günter Grass |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die Blechtrommel |

| Translator | Ralph Manheim, Breon Mitchell |

| Cover artist | Günter Grass |

| Country | West Germany |

| Language | German |

| Series | Danzig Trilogy |

| Genre | Magic realism |

| Publisher | Hermann Luchterhand Verlag |

Publication date | 1959 |

Published in English | 1961 |

| Pages | 576 |

| OCLC | 3618781 |

| 833.914 | |

| Followed by | Cat and Mouse |

The Tin Drum (German: Die Blechtrommel, pronounced [diː ˈblɛçˌtʁɔml̩] ⓘ) is a 1959 novel by Günter Grass, the first book of his Danzig Trilogy. It was adapted into a 1979 film, which won both the 1979 Palme d'Or and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1980.

To "beat a tin drum" means to create a disturbance in order to bring attention to a cause.[1][2][3]

Plot[edit]

The story revolves around the life of Oskar Matzerath, as narrated by himself when confined in a mental hospital during the years 1952–1954. Born in 1924 in the Free City of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), with an adult's capacity for thought and perception, he decides never to grow up when he hears his father declare that he would become a grocer. Gifted with a piercing shriek that can shatter glass or be used as a weapon, Oskar declares himself to be one of those "clairaudient infants", whose "spiritual development is complete at birth and only needs to affirm itself". He retains the stature of a child while living through the beginning of World War II, several love affairs, and the world of postwar Europe. Through all this, a toy tin drum, the first of which he received as a present on his third birthday, followed by many replacement drums each time he wears one out from over-vigorous drumming, remains his treasured possession; he is willing to commit violence to retain it.

Oskar considers himself to have two "presumptive fathers"—his mother's husband Alfred Matzerath, a member of the Nazi Party, and her cousin and lover Jan Bronski, a Danzig Pole who is executed for defending the Polish Post Office in Danzig during the German invasion of Poland. Oskar's mother having died, Alfred marries Maria, a woman who is secretly Oskar's first mistress. After marrying Alfred, Maria gives birth to Kurt, whom Oskar thereafter refers to as his son. But Oskar is disappointed to find that the baby persists in growing up, and will not join him in ceasing to grow at the age of three.

During the war, Oskar joins a troupe of performing dwarfs who entertain the German troops at the front line. But when his second love, the diminutive Roswitha, is killed by Allied troops in the invasion of Normandy, Oskar returns to his family in Danzig where he becomes the leader of a criminal youth gang (akin to the Edelweiss Pirates). The Red Army soon captures Danzig, and Alfred is shot by invading troops after he goes into seizures while swallowing his party pin to avoid being revealed as a Nazi. Oskar bears some culpability for both of his presumptive fathers' deaths since he leads Jan Bronski to the Polish Post Office in an effort to get his drum repaired and he returns Alfred Matzerath's Nazi party pin while he is being interrogated by Soviet soldiers.

After the war Oskar, his widowed stepmother, and their son have to leave the now Polish city of Danzig and move to Düsseldorf, where he models in the nude and works engraving tombstones. Mounting tensions compel Oskar to live apart from Maria and Kurt; he decides on a flat owned by the Zeidlers. Upon moving in, he falls in love with Sister Dorothea, a neighbour, but he later fails to seduce her. During an encounter with fellow musician Klepp, Klepp asks Oskar how he has an authority over the judgement of music. Oskar, willing to prove himself once and for all, picks up his drum and sticks despite his vow to never play again after Alfred's death, and plays a measure on his drum. The ensuing events lead Klepp, Oskar, and Scholle, a guitarist, to form the Rhine River Three jazz band. They are discovered by Mr. Schmuh, who invites them to play at the Onion Cellar club. After a virtuoso performance, a record company talent seeker discovers Oskar the jazz drummer and offers a contract. Oskar soon achieves fame and riches. One day while walking through a field he finds a severed finger: the ring finger of Sister Dorothea, who has been murdered. He then meets and befriends Vittlar. Oskar allows himself to be falsely convicted of the murder and is confined to an insane asylum, where he writes his memoirs.

Characters[edit]

The novel is divided into three books. The main characters in each book are:[4]

Book One[edit]

- Oskar Matzerath: Writes his memoirs from 1952 to 1954, age 28 to 30, appearing as a zeitgeist throughout historic milestones. He is the novel's main protagonist and unreliable narrator.

- Bruno Munsterberg: Oskar's keeper, who watches him through a peep hole. He makes knot sculptures inspired by Oskar's stories.

- Anna Koljaiczek Bronski: Oskar's grandmother, conceives Oscar's mother in 1899, which is when his memoir begins.

- Joseph Koljaiczek ("Bang Bang Jop" or "Joe Colchic"): Oskar's grandfather, a "firebug".

- Agnes Koljaiczek: Kashubian Oskar's mother.

- Jan Bronski: Agnes's cousin and lover. Oskar's presumptive father. Politically sided with the Poles.

- Alfred Matzerath: Agnes's husband. Oskar's other presumptive father. Politically sided with the Nazi Party.

- Sigismund Markus: A Jewish businessman in Danzig who owns the toy store where Oskar gets his tin drums. The store is ruined during the Danzig Kristallnacht.

Book Two[edit]

- Maria Truczinski: Girl hired by Alfred to help run his store after Agnes dies and with whom Oskar has his first sexual experience. She becomes pregnant and marries Alfred, but both Alfred and Oskar believe that they are Maria's child's father. She remains Oskar's family throughout the post-war years.

- Bebra: Runs the theatrical troupe of dwarfs which Oskar joins to escape Danzig. He is later the paraplegic owner of Oskar's record company. Oskar's lifelong mentor and role model. He is a musical clown.

- Roswitha Raguna: Bebra's mistress, then Oskar's. She is a beautiful Italian lady, but taller than Oskar, she has nevertheless chosen not to grow. She is the most celebrated somnambulist in all parts of Italy.

- "The Dusters": Danzig street urchins gang, Oskar leads as "Jesus" after he proves his mettle by smashing all the windows with his voice at the abandoned Baltic Chocolate Factory.

Book Three[edit]

- Sister Dorothea: A nurse from Düsseldorf and Oskar's love after Maria rejects him.

- Egon Münzer (Klepp): Oskar's friend. Self-proclaimed communist and jazz flautist.

- Gottfried Vittlar: Becomes friends with and then testifies against Oskar in the Ring Finger Case at Oskar's bidding.

Style[edit]

Oskar Matzerath is an unreliable narrator, as his sanity, or insanity, never becomes clear. He tells the tale in first person, though he occasionally diverts to third person, sometimes within the same sentence. As an unreliable narrator, he may contradict himself within his autobiography, as with his varying accounts of, but not exclusively, the Defense of the Polish Post Office, his grandfather Koljaiczek's fate, his paternal status over Kurt, Maria's son, and many others.

The novel is strongly political in nature, although it goes beyond a political novel in the writing's stylistic plurality. There are elements of allegory, myth and legend, placing it in the genre of magic realism.

The Tin Drum has religious overtones, both Jewish and Christian. Oskar holds conversations with both Jesus and Satan throughout the book. His gang members call him "Jesus", and he refers to himself as "Satan" later in the book.[4]

Critical reception[edit]

Initial reaction to The Tin Drum was mixed. It was called blasphemous and pornographic by some, and legal action was taken against it and Grass.[citation needed] However, by 1965 sentiment had cemented into public acceptance, and it soon became recognized as a classic of post-World War II literature, both in Germany and around the world.[4]

Translations[edit]

A translation into English by Ralph Manheim was published in 1961. A new 50th anniversary translation into English by Breon Mitchell was published in 2009.

Adaptations[edit]

Film[edit]

In 1979 a film adaptation appeared by Volker Schlöndorff. It covers only Books One and Two, concluding at the end of the war. It shared the 1979 Cannes Film Festival Palme d'Or with Apocalypse Now. It also won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film of 1979 at the 1980 Academy Awards.

Radio[edit]

In 1996 a radio dramatisation starring Phil Daniels was broadcast by BBC Radio 4.[5] Adapted by Mike Walker, it won the British Writers Guild award for best dramatisation.[6]

Theatre[edit]

The Kneehigh Theatre company performed an adaption of the novel in 2017 at the Everyman Theatre located in Liverpool.[7] The production features the story from Oskar's birth through the war, ending with Oskar marrying Maria.[citation needed]

In popular culture[edit]

- The Onion Cellar, a play by Amanda Palmer and Brian Viglione of The Dresden Dolls with the American Repertory Theater, is based on a chapter in The Tin Drum.

- Return to the Onion Cellar: A Dark Rock Musical, an original musical premiered in 2010 at the New York International Fringe Festival, references The Tin Drum and Günter Grass.[8]

- The futurist band Japan named their final studio album Tin Drum.

- The tin drum is featured in Season 2 of the Starz TV series Counterpart. Emily Silk is seen carrying it around as she attempts to recover her memory following an attempted assassination.

- In the series finale of Key and Peele, The Tin Drum is listed as one of the movies that Ray Parker Jr. wrote a song for on his greatest hits album.

- The Tin Drum is a book in the home bookcase in the film "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?".

Bibliography[edit]

- The Tin Drum. Random House, 1961, ISBN 9780613226820

- The Tin Drum. Vintage Books. 1990. ISBN 978-0-679-72575-6.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "The hypocrite's halo". The Washington Times. 20 August 2006.

- ^ Jeffrey Hart. "Response to "How the Right Went Wrong"". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 December 2006.

- ^ "IMDb: The Tin Drum (1979)". IMDb.

- ^ a b c Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Christopher Giroux and Brigham Narins. Vol. 88. Detroit: Gale Research, 1995. pp. 19-40. From Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Hanks, Robert (3 June 1996). "radio review". The Independent. Independent News & Media. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ "Music Details for Tuesday 4 February 1997". ABC Classic FM. ABC. 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ Love, Catherine (6 October 2017). "The Tin Drum review – Kneehigh turn Grass's fable into chaotic cabaret". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- ^ Return to the Onion Cellar: A Dark Rock Musical Archived 20 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

External links[edit]

- Grass, Günter (4 October 2009). "Guenter Grass - The Tin Drum". World Book Club (Interview). Interviewed by Harriet Gilbert. BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- Wunderlich, Dieter. "Die Blechtrommel Manuskript: 1956 - 1959". Dieter Wunderlich (in German). Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- Gioia, Ted. "The Tin Drum by Günter Grass". Conceptual Fiction. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022.