Raphael Cilento

Raphael Cilento | |

|---|---|

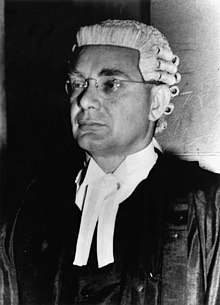

Cilento wearing legal robes in 1941 | |

| Leader of the Independent Democratic Party | |

| In office 1953–1954 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Party dissolved |

| Education | Teacher, medical practitioner |

| Known for | Aiding Refugees Post World War II |

| Spouse | Phyllis McGlew |

| Children | 6, including Margaret and Diane |

| Relatives | Jason Connery (grandson) |

| Medical career | |

| Institutions | Australian Army's Tropical Force Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine (1922-24) Commonwealth Government's Division of Tropical Hygiene (1928-34) Queensland Health Department United Nations refugees and displaced Persons (1946-47) Australian League of Rights |

| Sub-specialties | Administering Tropical Medicine |

| Research | Public health – tropical medicine |

| Awards | Knighted, 1935 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Raphael West Cilento 2 December 1893 Jamestown, South Australia |

| Died | 15 April 1985 (aged 91) Oxley, Queensland, Australia |

| Profession | Medical practitioner |

Sir Raphael West Cilento (2 December 1893 – 15 April 1985), often known as "Ray",[1] was an Australian medical practitioner and public health administrator.

Early life and education[edit]

Cilento was born in Jamestown, South Australia, in 1893, son of Raphael Ambrose Cilento, a stationmaster (whose father Salvatore had emigrated from Naples, Italy in 1855),[2] and Frances Ellen Elizabeth (née West).[1] His younger brother, Alan Watson West Cilento (born 1908), became General Manager of the Savings Bank of South Australia from 1961 to 1968.[3]

He was educated at Prince Alfred College,[3] but although he was determined from an early age to study medicine, he was initially thwarted in doing so due to lack of money. Therefore, he trained first as a school teacher, sponsored by the Education Department, from 1908 and taught at Port Pirie in 1910 and 1911.[1] He eventually entered the University of Adelaide Medical School on borrowed funds, but while there he won so many scholarships and other prizes that he ended his course with a respectable bank balance.[citation needed]

Early career[edit]

For the earlier part of his working life, Cilento's interests were mainly in public health and, specifically, tropical medicine. He served with the Australian Army's Tropical Force in New Guinea which superseded the German administration after the First World War. Later he joined the British colonial service in Malaya.

On his return to Australia he was Director of the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine in Townsville, Queensland, from 1922 to 1924.[1]

Middle career[edit]

Following a further term in New Guinea, Cilento became Director of the Commonwealth Government's Division of Tropical Hygiene in Brisbane. He held that role from 1928 to 1934.

In 1934, Queensland's Forgan Smith Government set out to create one of the world's first universally free public health systems. Minister for Health Ned Hanlon recruited Cilento to achieve this goal as Director-General of Health and Medical Services.[4] Cilento, despite his subsequent identification with the political right wing, never lost his belief in government-funded health care.[1] To assist in his policy-making objectives, he studied law and was admitted to the Bar in 1939.[1]

As Director-General (a position he held till 1945), and combined with the presidency of the state's Medical Board (as well as with the medicine professorship at the University of Queensland), he firmly opposed the anti-polio methods of Elizabeth Kenny, although at first he had spoken politely enough of her work to give the impression that he favoured it.

Cilento was knighted by King George V in 1935 (when only 42 years old) for his contributions to public service and tropical medicine.[5] He achieved international fame after World War II for his work in aiding refugees with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. In July 1945 he was the first civilian doctor to enter Belsen concentration camp, after doing considerable work on malaria control in The Balkans.[1] He was Director for Refugees and Displaced Persons from 1946 to 1947, and from 1948 was director of disaster relief in Palestine but resigned in 1950 after expressing sympathy with dispossessed Palestinian refugees.[1] He returned to Australia in 1951.

Later life[edit]

Cilento's later life in his native land was characterised by frustration at being unable to find appropriate employment in government service or academia. This failure was at least partly the consequence of his increasingly racist and ultra-conservative views, exemplified by his involvement with the Australian League of Rights during the 1950s and 1960s in particular, and his continued public support for the White Australia Policy long after this doctrine had ceased to be part of the Australian party-political mainstream. Professor Mark Finnane of Griffith University has written in the journal Queensland Review that "[m]uch of his brilliance, energetically applied to the development of sound research and policy in the control and eradication of tropical diseases, was directed also to applying the developing techniques of epidemiology and tropical medicine in the service of ideas about racial hierarchies which had a firm basis in the nineteenth century. These ideas eventually would be discredited by the history as well as science unfolding from the 1920s, but even so Cilento hung on to them well past their waning. Into the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, he was still writing about the white man in the tropics and racial vitality in ways that ensured his reputation for good work in other domains would struggle to survive his own monomania."[6]

In a letter in The Courier-Mail (18 May 1965) on Australian clergy's attitude to the Vietnam War he said 'I am not a practising Christian – I am sorry for it ... I regret that I have not the gift of faith'.

Cilento died on 15 April 1985 in the Brisbane suburb of Oxley and was survived by his wife and six children. Although he had been married in a Church of England service, he was brought up Catholic and was buried with Catholic rites at Pinnaroo Lawn Cemetery.[1][7]

Family[edit]

In 1918, whilst they were both studying medicine at the University of Adelaide, Cilento became engaged to, and on 18 March 1920 at St Columba's Church of England, Hawthorn he married Phyllis McGlew,[8] who also became a well-known medical practitioner and medical writer. They briefly set up in general practice in Tranmere before departing for Malaya in October.

Together they had three sons and three daughters. The three sons and Ruth became medical practitioners, Margaret became an artist, and Diane became an actress.[9]

- Raphael C. F. Cilento (19 February 1921 – 21 May 2012)[10] became a neurosurgeon. He married Billie Solomon in 1947,[11] and had four children: Adrienne, Julien, Vivienne and Raphael.[12] He took over his mother's practice in Brisbane in 1949. In 1953, he had a son Vivian Walker (later Kabul Oodgeroo Noonuccal) with Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo Noonuccal), who was working for his parents as a domestic servant.[13] He later divorced Billie and married Mavis Ross in 1958. They had five children: Penny, Giovanna, Abby, Naomi and Benjamin. His youngest son, Benjamin West Cilento, also became a physician who lived in the Houston, Texas area with his wife and three children. He is also an accomplished artist in his own right. From 1963–2007, Raphael was licensed to practise in New York. He had a fall in his early 80s that incapacitated him and he died of pneumonia at the age of 91.[14]

- Margaret Cilento (23 December 1923 - 21 November 2006) became a painter and printmaker. She grew up in Brisbane, moved to Sydney in 1943, and joined her father in New York in 1945. She spent most of the 1950s and early 1960s in Europe, marrying Geoffrey Maslen in 1963, and returned to Brisbane in 1965 to raise their family. She took up art again seriously around 2000, holding several exhibitions.[15]

- Ruth A Yolanda Cilento (30 July 1925 - 18 April 2016) graduated in medicine and surgery from Queensland University in 1949. She took up duty at Cairns Base Hospital in December 1949,[16] and married Westall David Smout in 1950.[17] In addition to a medical career, she had three children, is a sculptor, a sketcher, has an angora goat stud and wrote a children's book, Moreton Bay Adventure in 1961, which elder sister Margaret illustrated.[18]

- Carl Lindsay Cilento (1928-2004) married Diana Lauderdale Maitland in 1952.[19] They had six children: Peter (1953), Miranda (1955), Joanne and Belinda (1957), Richard (1961) and Madeline (1966).

- Elizabeth Diane Cilento[20] (2 April 1932[21][22][23][24][25][26] – 6 October 2011) was born in Brisbane.[22][23][25][26] She was an actress who married three times, secondly to Sean Connery, and was the mother of actor Jason Connery.[9]

- David Cilento (21 February 1936 - 8 November 2020)[27]

Other interests[edit]

- He twice attempted to enter parliament, once as a Democratic Party candidate for the Senate in the 1953 election, and as an Independent Democrat for the House of Representatives seat of McPherson in 1954.

- He was a member of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland[28] and its president in 1933–34, 1943–45 and 1953–68.

- He was member of the National Trust of Queensland and president from 1966 to 1971.[1]

Publications[edit]

Sir Raphael Cilento's publications include:

- Cilento, Raphael (1920) Climatic conditions in North Queensland : as they affect the health and virility of the people Brisbane : A.J. Cumming, Government Printer

- Cilento, Raphael (1925a) Preventive medicine and hygiene in the tropical territories under Australian control Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science. Wellington : Govt. Printer

- Cilento, Raphael (1925b) The white man in the tropics : with especial reference to Australia and its dependencies Service publication (Australia. Division of Tropical Hygiene) ; no.7. Melbourne : H.J. Green, Govt. Printer

- Cilento, Raphael (1936) Nutrition and numbers Livingstone lectures. Sydney : Camden College

- Cilento, Raphael (1944a) Blueprint for the health of a nation Sydney : Scotow Press

- Cilento, Raphael (1944b) Tropical diseases in Australasia: a handbook . Brisbane : W.R. Smith & Paterson. (2nd Edition)

- Cilento, Raphael & Lack, Clem (1959) "Wild white men" in Queensland : a monograph. Brisbane : W.R. Smith & Paterson for the Royal Historical Society of Queensland

- Cilento, Raphael& Lack, Clem. & Centenary Celebrations Council (Qld.) (Historical Committee) (1959), Triumph in the tropics : an historical sketch of Queensland / compiled and edited by Sir Raphael Cilento ; with the assistance of Clem Lack ; for the Historical Committee of the Centenary Celebrations Council of Queensland Smith & Paterson, Brisbane, Qld.

- Cilento, Raphael (1963) Medicine in Queensland : a monograph Council of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. Brisbane : Smith & Paterson.

- Cilento, Raphael (1972) Australia's racial heritage : an address Australian League of Rights Seminar, Melbourne, September 1971. Adelaide : Australian Heritage Society,

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mark Finnane, 'Cilento, Sir Raphael West (Ray) (1893–1985)' Archived 4 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 17, Melbourne University Press, pp 216-217.

- ^ Desmond O'Connor, Italians in South Australia: The first hundred years Archived 20 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, In D. O’Connor and A. Comin (eds) 1993. "Proceedings: the First Conference on the Impact of Italians in South Australia, 16–17 July 1993", Italian Congress: Italian Discipline, The Flinders University of South Australia: Adelaide, pp. 15-32.

- ^ a b Notable Australians ed. Cheryl Barnier Prestige Publishing Division of Paul Hamlyn Pty 1978; ISBN 0-86832-012-9

- ^ Morris, John Hunter QC (2006) "The Crisis in Decision-Making" Archived 22 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 4 March 2009

- ^ "CILENTO, Raphael West". It's an Honour. Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Finnane, Mark (2013). "Raphael Cilento in medicine and politics: Visions and contradictions" (PDF). Queensland Review. 20 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1017/qre.2013.2. hdl:10072/57075. ISSN 1321-8166. S2CID 145387263.

- ^ Cilento Raphael Archived 21 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine — Brisbane City Council Grave Location Search. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- ^ Mary D. Mahoney, 'Cilento, Phyllis Dorothy (1894–1987)' Archived 4 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 17, Melbourne University Press, pp 214-215.

- ^ a b Diane Cilento Interview transcript, Australian Biography (SBS TV), 2000.

- ^ Raphael (Raff) Charles Frederic Cilento

- ^ "Doctor Weds". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 1 February 1947. p. 6. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "From Ship To Church". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 20 April 1948. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Oodgeroo Noonuccal (1920–1993)". Australian Poetry Library. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "Five Doctors in Cilento Family". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 10 March 1949. p. 9. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Margaret Cilento Archived 27 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Dictionary of Australian Artists Online, www.daao.org.au

Photo circa 1950 Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine from Angus Trumble's blog Archived 23 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Caption: On the way back to England by way of the Riviera, the party went on another boat trip to see the Calanques at Cassis, not far from Marseilles. Left to right, André, Margaret Cilento [the artist; daughter of Sir Raphael and Lady Cilento, and older sister of the actress Diane Cilento], Boatman, and Nipper.

Pictures of 69 of Margaret's works can be found on The National Library of Australia website Archived 15 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

Run away to paint the circus Archived 5 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 15 June 2005, Sydney Morning Herald

Breaking New Ground Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 27 July to 30 September 2007, QUT Art Museum. "Education kit" Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

"Circus – Dream and Reality". eva breuer art dealer. 18 June 2005. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. - ^ "Hospital Medical Staff". The Cairns Post. Qld.: National Library of Australia. 20 December 1949. p. 5. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Went to altar in wrong shoes". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 15 July 1950. p. 8. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Dr Ruth Cilento Archived 3 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine, www.ruthcilento.com

Moreton Bay adventure / Ruth Cilento ; illustrated by Margaret Cilento, National Library of Australia - ^ "Confetti and Tulle". The Courier-Mail. Brisbane: National Library of Australia. 17 April 1952. p. 8. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ The Concise Encyclopedia of Australia and New Zealand. Horwitz Publications. 1982. p. 286.

- ^ "Diane Cilento". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Cilento, Diane (1932–2011)". snaccooperative.org.

- ^ a b Australian Biography Series 8: Diane Cilento, Kanopy Streaming, 2015

- ^ "Diane Cilento". Queensland University of Technology (QUT) Library. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013.

- ^ a b Moran, Albert; Keating, Chris (2009). The A to Z of Australian Radio and Television. Scarecrow Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780810870222.

- ^ a b Famous People Born in April 1932 - On This Day

- ^ "CILENTO, Dr David". The Courier-Mail. 21 November 2020.

- ^ Welcome to The Royal Historical Society of Queensland Archived 8 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Royal Historical Society of Queensland, www.queenslandhistory.org.au

Sources[edit]

- Fisher, Fedora (1994), Raphael Cilento, A Biography, University of Queensland Press, ISBN 0-7022-2438-3

- Martyr, Philippa J. (2002), Paradise of Quacks: An Alternative History of Medicine in Australia, Macleay Press, Sydney, ISBN 1-876492-06-6

Further reading[edit]

- McGregor, Russell (2009), "The White Man in the Tropics" (PDF), Sir Robert Philp Lecture Series : selected lectures on North Queensland history from the CityLibraries, Townsville City Council, pp. 58–67, ISBN 978-0-9807305-2-4, archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2020