Phryne

Phryne (/ˈfraɪni/; Ancient Greek: Φρύνη, romanized: Phrū́nē, c. 371 BC – after 316 BC) was an ancient Greek hetaira (courtesan). From Thespiae in Boeotia, she was active in Athens, where she became one of the wealthiest women in Greece. She is best known for her trial for impiety, where she was defended by the orator Hypereides. According to legend, she was acquitted after baring her breasts to the jury, though the historical accuracy of this episode is doubtful. She also modeled for the artists Apelles and Praxiteles, and the Aphrodite of Knidos was based on her. Largely ignored during the renaissance, artistic interest in Phryne began to grow from the end of the eighteenth century; her trial was famously depicted by Jean-Léon Gérôme in the 1861 painting Phryne Before the Areopagus.

Life[edit]

Phryne was from Thespiae in Boeotia,[1] though she seems to have spent most of her life in Athens.[a][2] She was probably born around 371 BC,[b] and was the daughter of Epicles.[3] Both Plutarch and Athenaeus say that Phryne's real name was Mnesarete.[5][6] According to Plutarch she was called Phryne because she had a yellow complexion like a toad (in Greek: φρύνη);[5] she also used the name Saperdion.[3] Phryne apparently grew up poor – comic playwrights portray her picking capers – and became one of the wealthiest women in the Greek world.[3] According to Callistratus, after Alexander razed Thebes in 335, Phryne offered to pay to rebuild the walls.[7] She probably lived beyond 316 BC, when Thebes was rebuilt.[3] She was also said to have dedicated a statue of herself at Delphi, and a statue of Eros to Thespiae.[8]

Very little is known about Phryne's life for certain, and much of her biography transmitted in ancient sources may be invented: Helen Morales writes that separating fact from fiction in accounts of Phryne's life is "impossible".[9]

Trial[edit]

The most famous event in Phryne's life was the prosecution brought shortly after 350 BC by Euthias, where she was defended by Hypereides.[3] According to legend, Hypereides exposed Phryne's breasts to the jury, who were so struck by her beauty that she was acquitted.[10]

According to the ancient sources, Phryne was charged with asebeia, a kind of blasphemy.[c] An anonymous treatise on rhetoric, which summarises the case against Phryne, lists three specific accusations against her – that she held a "shameless komos" or ritual procession, that she introduced a new god, and that she organised unlawful thiasoi or debauched meetings.[14] The new god that Phryne was supposed to have introduced to Athens was named by Harpocration as Isodaites; however, though Harpocration describes him as being "foreign" and "new", the name is Greek[15] and other sources consider it an epithet of Dionysus, Helios, or Pluto.[16]

The case against Phryne was brought by Euthias, one of her former lovers; Hypereides, who spoke in her defence, was also one of Phryne's lovers.[17][d] According to an ancient tradition, Euthias' case against Phryne was motivated by a personal quarrel rather than Phryne's alleged impiety.[19] Craig Cooper suggests that the trial of Phryne was politically motivated, noting that Aristogeiton was a political enemy of Hyperides who brought a prosecution against him for illegally introducing a decree around the same time as the trial of Phryne.[20] Hypereides' defence speech survives only in fragments, though it was hugely admired in antiquity.[21] Two prosecution speeches are mentioned by Athenaeus, though neither survive – one composed by Anaximenes of Lampsacus and delivered by Euthias, the other composed by Aristogeiton.[22]

Famously, Phryne was said to have been acquitted after the jury saw her bare breasts – Quintilian says that she was saved "non Hyperidis actione... sed conspectus corporis" ("not by Hyperides' pleading, but by the sight of her body").[23] Three different versions of this story survive – in Quintilian's account, along with those of Sextus Empiricus and Philodemus, it is Phryne who makes the decision to expose her own breasts; while in Athenaeus' version Hypereides exposed Phryne as the climax of his speech, and in Plutarch's version Hypereides exposed her because he saw that his speech had failed to persuade the jury.[24] Christine Mitchell Havelock notes that there is separate evidence for women being brought into the courtroom to arouse the sympathy of the jury, and that in ancient Greece baring the breasts was a gesture intended to arouse such a compassionate response, so Phryne's supposed behaviour in the court is not without parallel in Greek practice.[25] However, this episode probably never happened. It was not mentioned in Posidippus' version of the trial in his comedy Ephesian Woman, quoted by Athenaeus. Ephesian Woman was produced c.290 BC, and the story of Phryne bearing her breasts therefore probably postdates this.[10] In Posidippus' version, Phryne personally pleaded with each of the jurors at her trial for them to save her life, and it was this which secured her acquittal.[26] The story of Phryne baring her breasts may have been invented by Idomeneus of Lampsacus.[27] Though all of the ancient accounts assume that Phryne was on trial for her life, asebeia was not necessarily punished by death; it was an agōn timētos, in which the jury would decide on the punishment if the accused was convicted.[13]

Hermippus reports that after Phryne's acquittal, Euthias was so furious that he never spoke publicly again.[28] Kapparis suggests that in fact he was disenfranchised, possibly because he failed to gain one fifth of the jurors' votes and was unable to pay the subsequent fine.[29]

Model[edit]

Phryne was the model for two of the great artists of classical Greece, Praxiteles and Apelles. According to Athenaeus, Apelles saw Phryne walk naked into the sea at Eleusis, and inspired by this sight used her as a model for his painting of Aphrodite Anadyomene (Aphrodite Rising from the Sea). This work was on display at the sanctuary of Asclepius on the Greek island of Kos, and by the first century AD it appears to have been one of Apelles' best-known works.[30]

Praxiteles also based a depiction of Aphrodite on Phryne – the Aphrodite of Knidos, the first three-dimensional and monumentally-sized female nude in ancient Greek art.[31] He also produced a golden or gilt statue of Phryne which was displayed – according to Pausanias dedicated by Phryne herself – in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi.[32] This may have been the first female portrait ever dedicated at Delphi; it was certainly the only statue of a woman alone to be dedicated before the Roman period.[33]

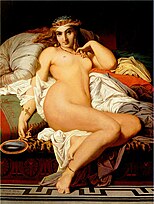

Reception[edit]

Phryne was largely ignored during the Renaissance, in favour of more heroic female figures such as Lucretia, but interest in her story increased towards the end of the eighteenth century. Early depictions of her by Angelica Kauffmann and J. M. W. Turner avoid eroticising her, but in the latter half of the nineteenth century, French academic painters focused more on the eroticism of Phryne's life.[34] The most famous nineteenth century depiction of Phryne was Jean-Léon Gérôme's Phryne before the Areopagus, which was controversial for showing her covering her face in shame, in the same pose that Gérôme used in several paintings of slaves in Eastern slave-markets.[35] Driven by this controversy, Gérôme's painting was widely reproduced and caricatured, with engravings by Léopold Flameng, a bronze by Alexandre Falguière, and a painting by Paul Cézanne all modelled after Gérôme's Phryne.[36] In nineteenth century literature, Phryne appears in "Lesbos" from Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal, where she is used metonymically to represent courtesans in general, and in Rainer Maria Rilke's Die Flamingos, in which the flamingos are compared to Phryne, as they seduce themselves – by folding their wings over their own heads – more effectively than even she could ("they seem to think / themselves seductive; that their charms surpass / a Phryne’s").[37][38]

In the twentieth century, Phryne made the transition to cinema. Alessandro Blasetti's "Il processo di Frine" adapted the story of Phryne's trial with a contemporary setting, based on a short story by Edoardo Scarfoglio; the following year, the peplum film Frine cortigiana d'Oriente ("Phryne, the Oriental Courtesan") was released. Both films depict Phryne's disrobing at her trial with an iconography influenced by Gérôme's painting.[34]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Though a citizen of Thespiae, she may even have been born in Athens as many Thespians moved there after the conquest of Thespia by Thebes in 373 BC.[2]

- ^ Laura McClure says about 371 BC;[3] Konstantinos Kapparis says about 370;[2] Uwe Walter says before 371.[4]

- ^ Though the ancient sources are unanimous in saying that the charge against Phryne was asebeia, scholars such as David Phillips have proposed that she was in fact prosecuted through an eisangelia (usually translated as "impeachment", a procedure reserved for serious offences against the state;[11] cases of impiety were more usually tried through a graphē asebeias[12]) based on the fact that the death penalty appears to be taken for granted by many of the ancient sources on Phryne's trial. Konstantinos Kapparis argues that the assumption of a death penalty can instead be explained as "invention and wild story-telling".[13]

- ^ At least, so the ancient biographical tradition claimed; Craig Cooper has argued that the account of the trial preserved in ancient sources has "all the hallmarks of being a biographical fiction".[18]

References[edit]

- ^ Eidinow 2016, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Kapparis 2018, p. 440.

- ^ a b c d e f McClure 2014, p. 127.

- ^ Walter 2006.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Moralia "De Pythiae oraculis" 14

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 13.60

- ^ Davidson 1997, p. 106.

- ^ Kapparis 2018, pp. 321–323.

- ^ Morales 2011, p. 72.

- ^ a b Eidinow 2016, pp. 24–5.

- ^ Phillips 2013, p. 464.

- ^ Phillips 2013, p. 408.

- ^ a b Kapparis 2018, p. 261.

- ^ Eidinow 2016, pp. 26–7.

- ^ Eidinow 2016, p. 29.

- ^ Versnel 1990, p. 119.

- ^ Morales 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Cooper 1995, p. 305.

- ^ O'Connell 2013, p. 113.

- ^ Cooper 1995, p. 306, n. 10.

- ^ Eidinow 2016, p. 24.

- ^ McClure 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Morales 2011, p. 78.

- ^ Morales 2011, pp. 76–7.

- ^ Havelock 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Kapparis 2018, p. 259.

- ^ Cooper 1995, p. 315.

- ^ Hermippus fr.50 Müller = Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 13.60

- ^ Kapparis 2018, p. 261, n. 332.

- ^ Havelock 2007, p. 86.

- ^ Havelock 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Keesling 2006, pp. 66–7.

- ^ Keesling 2006, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Cavallini.

- ^ Ryan 1993, pp. 1134–1135.

- ^ Ryan 1993, pp. 1135–1136.

- ^ Ryan 1993, pp. 1130–1131.

- ^ Rilke 2015, p. 345.

Works cited[edit]

- Cavallini, Eleonora, "Phryne in Modern Art, Cinema, and Cartoon", MythiMedia, archived from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 3 March 2016

- Cooper, Craig (1995), "Hypereides and the Trial of Phryne", Phoenix, 49 (4): 303–318, doi:10.2307/1088883, JSTOR 1088883

- Davidson, James (1997), Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens, London: Harper Collins

- Eidinow, Esther (2016), Envy, Poison, and Death: Women on Trial in Classical Athens, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Havelock, Christine Mitchell (2007), The Aphrodite of Knidos and Her Successors: A Historical Review of the Female Nude in Greek Art, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

- Kapparis, Konstantinos (2018), Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World, Berlin: De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-055795-4

- Keesling, Catherine (2006), "Heavenly Bodies: Monuments to Prostitutes in Greek Sanctuaries", in Faraone, Christopher; McClure, Laura (eds.), Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press

- McClure, Laura (2014), Courtesans at Table: Gender and Greek Literary Culture in Athenaeus, New York: Routledge

- Morales, Helen (2011), "Fantasising Phryne: The Psychology and Ethics of Ekphrasis", The Cambridge Classical Journal, 57 (1): 71–104, doi:10.1017/S1750270500001287, S2CID 145580288

- O'Connell, Peter (2013), "Hyperides and Epopteia: A New Fragment of the Defense of Phryne", Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 53

- Phillips, David (2013), The Law of Ancient Athens, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

- Rilke, Rainer Maria (2015) [1906], New Poems, translated by Len Krisak, Boydell & Brewer

- Ryan, Judith (1993), "More seductive than Phryne: Baudelaire, Gérôme, Rilke, and the problem of autonomous art", PMLA, 108 (5)

- Versnel, H. S. (1990), Ter Unus: Isis, Dionysos, Hermes. Three Studies in Henotheism, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9004-09268-4

- Walter, Uwe (2006), "Phryne", Brill's New Pauly, doi:10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e924270