Petrashevsky Circle

Petrashevsky Circle Петрашевцы | |

|---|---|

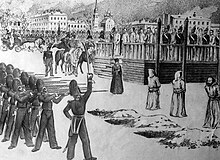

Petrashevsky Circle's members going through an 'execution ritual', an example of a mock execution. St. Petersburg, Semionov-Plaz, 1849. B. Pokrovsky's drawing | |

| Leader | Mikhail Petrashevsky |

| Founded | 1845 |

| Dissolved | 1849 |

| Headquarters | Saint Petersburg |

| Ideology | Utopian socialism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

The Petrashevsky Circle was a Russian literary discussion group of progressive-minded intellectuals in St. Petersburg in the 1840s.[1] It was organized by Mikhail Petrashevsky, a follower of the French utopian socialist Charles Fourier. Among the members were writers, teachers, students, minor government officials and army officers. While differing in political views, most of them were opponents of the tsarist autocracy and Russian serfdom. Like that of the Lyubomudry group founded earlier in the century, the purpose of the circle was to discuss Western philosophy and literature that was officially banned by the Imperial government of Tsar Nicholas I. Among those connected to the circle were the writers Dostoevsky and Saltykov-Shchedrin, and the poets Aleksey Pleshcheyev, Apollon Maikov, and Taras Shevchenko.[2]

Nicholas I, alarmed at the prospect of the revolutions of 1848 spreading to Russia, saw great danger in organisations like the Petrashevsky Circle. In 1849, members of the Circle were arrested and imprisoned. A large group of prisoners, Dostoevsky among them, were sent to Semyonov Place for execution. As they stood in the square waiting to be shot, a messenger interrupted the proceedings with notice of a reprieve. As part of a pre-planned intentional deception, the Tsar had prepared a letter to general-adjutant Sumarokov, commuting the death sentences to incarceration. Some of the prisoners were sent to Siberia, others to prisons. Dostoevsky's eight-year sentence was later reduced to four years by Nicholas I.

Origins and activities of the circle[edit]

In the early 1840s, Petrashevsky had attended Viktor Poroshin's lectures on socialist systems at the University of St Petersburg. He was particularly impressed by the utopian ideas of Charles Fourier, and "devoted himself to propagating his new faith".[3] He began accumulating a large library of forbidden books and invited friends to visit for the purpose of discussing the new ideas.[4] By 1845 the circle had grown considerably, and Petrashevsky became a well-known figure in Petersburg social and intellectual life. Dostoevsky began attending the Petrashevsky 'Fridays' in 1847, at the time seeing the discussions as ordinary social occasions with nothing particularly conspiratorial about them. There was a wide diversity of points of view, from atheistic socialists influenced by Hegel and Feuerbach to deeply-religious poets and literary artists, but all held in common a desire for greater freedom in Russian social life and a passionate opposition to the enslaved status of the Russian peasantry.[5]

As Tsar Nicholas had made it clear that he too opposed enslavement, there was not much sense of political conspiracy in the circle at that time. That changed after the 1848 revolutions in Europe, when it became apparent that the kinds of social transformation occurring there would be aggressively stifled by the ruling classes in Russia. Membership of the circle increased, but discussions became more serious, formal and secretive. Petrashevsky, who had always tended to flaunt his iconoclasm, had for some time been a person of interest to the secret police, but they now decided to place him under close surveillance. An agent, Antonelli, was deployed in Petrashevsky's department in January 1849, ingratiated himself, began attending the meetings of the circle and reported to his superiors.[6]

Speshnev's secret society[edit]

The government's concerns were not without foundation. The aristocrat Nikolay Speshnev, who began attending the Fridays in early 1848, was resolutely in favour of promoting the socialist cause by any means possible, including terrorism, and sought to form his own secret society within the circle. According to Speshnev, infiltration, propaganda and revolt should be the three methods of illegal action for a secret society. He and Petrashevsky held meetings with a charismatic Siberian figure, Rafael Chernosvitov, to discuss the possibility of co-ordinated armed revolts. Speshnev's associate, the army lieutenant Nikolay Mombelli, initiated a series of conversations promoting the idea of organised infiltration of the bureaucracy to counter government measures. Mombelli suggested that all members should submit their biography and that traitors be executed.

Petrashevsky, though party to the conversations, consistently urged against the adoption of violent methods. Speshnev, therefore, continued the formation of the society without him and succeeded in recruiting a number of talented members, including Dostoevsky. Although no real action was taken by the group, Dostoevsky had no doubt that there was a "conspiracy in intent", which included promoting dissatisfaction with the current order and establishing connections with already discontented groups such as religious dissidents and serfs. Found among Speshnev's papers after his arrest was a prototype "oath of allegiance" in which the signer would pledge obedience to a central committee and a willingness to be available at any time for whatever violent means were deemed necessary for the success of the cause. Speshnev's secret society was never discovered by the authorities, but under threat of torture he confessed to the original discussions within the Petrashevsky Circle.[7]

Palm-Durov circle[edit]

The growth of the circle led to the formation of a number of satellite groups, most notably the Palm-Durov Circle which met at the shared apartment of the writers Alexander Palm and Sergey Durov. According to Dostoevsky, the original purpose of this group had been to publish a literary almanac. Speshnev follower Pavel Filippov convinced them to actively produce and distribute anti-government propaganda, and two works of this kind were in fact produced, both of which were later discovered by the police. The first—a sketch entitled "A Soldier's conversation"—was an exhortation of the popular uprising in France aimed at a peasant audience, and was written by another Speshnev associate, the army officer Nikolay Grigoryev. The second, by Filippov, was a rewriting of the Ten Commandments that characterized various acts of revolt against oppression as being in conformity with the will of God.

When a plan was made to reproduce the articles on a lithograph, Palm and Durov became anxious about continuing the circle, and its activities wound down. When Petrashevsky heard about the plans he too voiced his opposition, arguing that revolts could lead to despotism and that judicial reform should be their primary goal. The conflict brought into the open a clear division in the circle between activists and moderates.[8]

Belinsky's letter to Gogol[edit]

Two of the best-known writers associated with the Petrashevsky Circle, Valerian Maykov and Vissarion Belinsky, died before it was broken. Maykov was very close to Petrashevsky and took a large part in the compilation of Kirillov's work Dictionary of Foreign Words, which became part of the corpus delicti of the trial process. Belinsky, the author of Letter to Gogol, would have been classified as a dangerous criminal since many of the Petrashevsky Circle members' only fault had been participation in the dissemination of the text of the letter. The letter was a passionate and extreme denunciation of Nikolai Gogol's loyalty to the autocracy and the Russian Orthodox Church. It claimed, for example, that the church "has always served as the prop of the knout and the servant of despotism."[9] The letter was read aloud by Dostoevsky and produced a response of universal approval and excitement that transcended the deepening divisions within the circle. Filippov and Mombelli made copies and began distributing them, but Petrashevsky again tried to calm the rising sense of urgency by insisting that judicial reform was the best way forward for the peasantry.[10]

Arrest and trial[edit]

Shortly after the meetings centering on Belinsky's letter, the arrests began. All those associated with the letter were treated harshly, some merely for 'failure to report' on those who took part in publishing it. Among these was the poet Pleshcheyev who, according to the verdict, "for distributing Belinsky's letter, was deprived of all rights of the state and sent to hard labor in factories for 4 years." Some members escaped prosecution. These included V. A. Èngel (later an active participant in Herzen's Polar Star), Dostoevsky's brothers Andrey and Mikhail (who had strenuously opposed the publication of provocative material), well-known Slavophile theorist Nikolai Danilevsky, writer Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, and the poet Apollon Maykov (Valerian's brother).

After the arrests on April 22, 1849, the members of the circle were at first detained at the Peter and Paul Fortress. The Commission of Inquiry headed by General Nabokov questioned the prisoners individually on the basis of information supplied by Antonelli, and documents confiscated at the time of the arrest. The trial was to take place according to military law rather than the far more lenient civil law. Of the sixty men originally arrested, fifteen were sentenced to execution by firing squad, others to hard labour and exile. Reviewing the decision the highest military court, the General-Auditariat, ruled that a judicial error had been made and that all the remaining prisoners should be executed. However, when submitting the sentence to the Tsar they included a plea for mercy and a list of lesser sentences.

Mock execution and exile[edit]

The Tsar agreed to the lesser sentences, but gave explicit instructions that only after the entire ritual of preparation for execution had been completed should the prisoners be told that their lives had been spared by an act of imperial grace. On the morning of December 22 the prisoners were taken from their cells without explanation and transported to Semonovsky Square. The sentence of death by firing squad was read out over them, and the first three prisoners—Petrashevsky, Mombelli and Grigoryev—were seized and tied to stakes in front of the firing squad. A minute elapsed before the drum roll indicating retreat was heard and the soldiers lowered their rifles. Grigoryev, who in prison had been showing signs of derangement, completely lost his senses, and spent the remainder of his days as a helpless mental invalid. Dostoevsky, who had been next in line, recalled the experience twenty years later in The Idiot: "The uncertainty and feeling of aversion for the new thing which was going to overtake him immediately, was terrible".[11] An aide-de-camp arrived carrying the Tsar's pardon and the commuted sentences. Swords were broken over the heads of the prisoners, signifying exclusion from civilian life henceforth. They were placed in shackles, and preparations began for their transport to Siberia.[12]

After serving four to six years of imprisonment and hard labour, the prisoners' sentences were commuted to exile and service in the army. The members of the circle exiled to Siberia and the Kazakh steppe influenced the nascent Kazakh intelligentsia. One of the most notable interlocutors of Dostoevsky during his time of exile was the Kazakh scholar and military officer Chokan Valikhanov. Speshnev edited a newspaper in Irkutsk from 1857 to 1859.[13] Some, such as Petrashevsky, died in exile, but both Speshnev and Dostoevsky were allowed to return to Petersburg in late 1859, exactly ten years after their departure. In 1860 Dostoevsky published Notes From the House of the Dead, a novel based on his experiences in katorga and exile.[14] In 1871 he published Demons, a novel that drew to some extent on his experiences with the Petrshevsky Circle and Speshnev's conspiratorial group. The central character of the novel, Nikolai Stavrogin, was inspired by Speshnev.[15]

List of Petrashevists[edit]

- Mikhail Petrashevsky, titular councilor, 27 years old

- Dmitry Akhsharumov, Ph.D. St. Petersburg State University, 26 years old

- Hippolyte Deboo, serving in the Asian Department, 25 years old

- Konstantin Deboo, serving in the Asian Department, 38 years old

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky, a retired engineer lieutenant, writer, 27 years old

- Sergei Durov, a retired collegiate assessor, writer, 33 years old

- Vasily Golovinski, titular councilor, 20 years old

- Nikolai Petrovich Grigoriev, Lieutenant Guards Horse-Grenadier Regiment

- Alexander Evropeus, a retired collegiate secretary, 2? years old

- Basil Kamen, the son of honorary citizen, 19 years old

- Nikolay Kashkin, serving in the Asian Department, 20 years old

- Fedor Lvov, captain of the Life Guards regiment of Chasseurs, 25 years old

- Nikolay Mombelli, the lieutenant of the Life Guards regiment of Moscow, 27 years old

- Alexander Palm, lieutenant of the Life Guards regiment of Chasseurs, 27 years old

- Aleksey Pleshcheyev, non-serviceman, writer, 23 years old

- Nikolay Speshnev, lord of the Kursk province, 28 years old

- Konstantin Timkovsky, titular councilor, 35 years old

- Felix Toll, master chief engineering school, 26 years old

- Pavel Filippov, a student at St. Petersburg University, 24 years old

- Alexander Khanykov, a student at St. Petersburg University, 24 years old

- Raphael Chernosvitov, a retired lieutenant colonel (former superintendent), 39 years old

- Peter Shaposhnikov, a tradesman, 28 years old

- Ivan Yastrzhembsky, Assistant Inspector in the Institute of Technology, 34 years old

- Alexander Balasoglo, a poet, a retired naval officer, 36 years old

References[edit]

- ^ Evans, John L. The Petraševskij Circle 1845-1849. The Hague: Mouton, 1974.

- ^ Lenin: Plan of Letters on Tasks of the Revolutionary Youth

- ^ Frank (2010), p. 137.

- ^ Birmingham, Kevin. 2021. The sinner and the saint: Dostoevsky and the gentleman murderer who inspired a masterpiece. New York: Penguin.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 139–40.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 141–2.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 145–51.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 152–8.

- ^ Belinsky, Vissarion. "Letter to Gogol". marxists.org. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 157–9.

- ^ Dostoevsky, Fyodor (1996). The Idiot. Wordsworth Editions. p. 54. ISBN 1 85326 175 0.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 163–80.

- ^ "The Great Soviet Encyclopedia 3rd edition". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 273–6.

- ^ Frank (2010), pp. 145, 645.

- Frank, Joseph (2010). Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1.