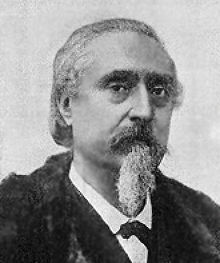

Paolo Mantegazza

Paolo Mantegazza | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1831-10-31 |

| Died | 2010-08-28 San Terezo (La Spezia) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | University of Pisa, University of Milan; Doctorate of Medicine at University of Pavia |

| Known for | Experiments relating to coca and cognition |

| Movement | Liberal; Darwinist |

| Parent |

|

Paolo Mantegazza (Italian pronunciation: [ˈpaːolo manteˈɡattsa]; 31 October 1831 – 28 August 1910) was an Italian neurologist, physiologist, and anthropologist, known for his experimental investigation of coca leaves and its effects on the human psyche. He was also an author of fiction.

Life[edit]

Mantegazza was born in Monza on 31 October 1831. After spending his student days at the universities of Pisa and Milan, he gained his M.D. degree at the University of Pavia in 1854. After travelling in Europe, India and the Americas, he practised as a doctor in Argentina and Paraguay. He returned to Italy in 1858 he was appointed surgeon at Milan Hospital and professor of general pathology at the University of Pavia. In 1870, he was nominated professor of anthropology at the Istituto di Studi Superiori in Florence. Here, he founded the first Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Italy, and later the Italian Anthropological Society.

From 1865 to 1876, he was deputy for Monza in the Parliament of Italy, and was subsequently elected to the Italian Senate. He became the object of fierce attacks because of the extent to which he practised vivisection.[1]

In 1879, Mantegazza travelled to Norway with his colleague Stephan Sommier on a quest to collect "anthropological facts" about the Sámi. He gathered three types of information: cultural items, anthropometric measurements, and photographs. The last category featured images he and Sommier had created as well as photos he had taken along the way. All of them were returned to Florence, where Mantegazza was the director of the anthropological museum.

Mantegazza was elected an International Member of the American Philosophical Society in 1895.[2]

In 1897, he published his novel The Year 3000: A Dream; through this work he projected that future citizens would have air conditioning, renewable electricity, credit cards, and virtual-reality entertainment, as well as a massive war in Europe, which would be followed by peace, integration, and a unified currency.[3]

During a time when the popular and official science and culture in Italy were still influenced by the Roman Catholic Church, Mantegazza was a staunch liberal and defended the ideas of Darwinism in anthropology, his research having helped to establish it as the "natural history of man". He also maintained a correspondence with Charles Darwin from 1868 to 1875.

Mantegazza's natural history, however, must be considered to be from a racial or social Darwinist perspective, evident in his Morphological Tree of Human Races. This tree maps three principles: a single European meta-narrative controls all of the world's many cultures; human history imagined as progressive, with the European human as the pinnacle of progress and development; and lastly, a ranking of different races onto a hierarchical structure. The hierarchy was structured similarly to a tree, with the Aryan race as the topmost branch, followed by Polynesians, Semites, Japanese, and moving downward to the bottom-most branch, the "Negritos." Mantegazza also designed an "Aesthetic Tree of the Human Race" with similar results.

Mantegazza believed drugs and certain foods would change humankind in the future, and defended the experimental investigation and use of cocaine as one of these miracle drugs. When Mantegazza returned from South America, where he had witnessed the use of coca by indigenous people, he was able to chew a regular amount of coca leaves and then tested them on himself in 1859. Afterward, he wrote a paper titled Sulle Virtù Igieniche e Medicinali della Coca e sugli Alimenti Nervosi in Generale ("On the hygienic and medicinal properties of coca and on nervous nourishment in general"). He noted enthusiastically the powerful stimulating effect of cocaine in coca leaves on cognition:

"... I sneered at the poor mortals condemned to live in this valley of tears while I, carried on the wings of two leaves of coca, went flying through the spaces of 77,438 words, each more splendid than the one before...An hour later, I was sufficiently calm to write these words in a steady hand: God is unjust because he made man incapable of sustaining the effect of coca all life long. I would rather have a life span of ten years with coca than one of 10 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 centuries without coca."

Mantegazza died at San Terenzo (La Spezia) on 28 August 1910.

Works[edit]

Mantegazza's published works also included:

- Fisiologia del Dolore (Physiology of Pain, 1880);

- Fisiologia dell'Amore (Physiology of Love, 1896);

- Elementi d'igiene (Elements of Hygiene, 1875);

- Fisonomia e Mimica (Physiognomy and Mimics, 1883);

- Gli Amori degli Uomini (The Sexual Relations of Mankind, 1885);

- Fisiologia dell'odio, (Physiology of Hate, 1889);

- Fisiologia della Donna (Physiology of Women, 1893).

His philosophical and social views were published in a 1,200-page volume in 1871, titled Quadri della Natura Umana. Feste ed Ebbrezze ("Pictures of Human Nature. Feasts and Inebriations"). Many consider this opus his masterpiece.

As a fiction writer, Mantegazza was very original. He wrote a romance on the marriage between people with disease, Un Giorno a Madera (1876), which made quite a sensation. Less well known is his science fiction and futuristic romance L'Anno 3000 (The Year 3000, written in 1897).

He also wrote the novel Testa ("Head", 1887), a sequel of renowned book Heart, by his friend Edmondo de Amicis. The novel tells the story of Enrico in his teenager years.

Bibliography[edit]

- Mantegazza, P.: L'Anno 3000. Milano, 1897. (in Italian: Zipped RTF full text from Nigralatebra, or HTML full text with concordance from IntraText Digital Library).

- Mantegazza, P.: The Year 3000. A Dream. Edited, with an introduction and notes, by Nicoletta Pireddu. Transl. by David Jacobson. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

- Mantegazza, P.: Fisiologia da Mulher. (in Portuguese) translated by Cândido de Figueiredo. Lisbon, Livraria Clássica Editora, 1946.

- Mantegazza, P.: The Physiology of Love and Other Writings. Edited, with an introduction and notes, by Nicoletta Pireddu. Transl. by David Jacobson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

- Mantegazza, P.: Un Giorno a Madera. (in Italian: HTML full text with concordance from IntraText Digital Library).

- Mantegazza, P.: Studi sui Matrimoni Consanguini. (in Italian: HTML full text with concordance from IntraText Digital Library).

- The Darwin-Mantegazza Correspondence. The Darwin Correspondence On-Line Database.

- Giovanni Landucci, Darwinismo a Firenze. Tra scienze e ideologia (1860-1900), Firenze, Olschki 1977, chapters 4 and 5.

- Giovanni Landucci, L'occhio e la mente. Scienza e filosofia nell'Italia dell'Ottocento, L. Olschki, Firenze 1987, ch. 3. - ISBN 88-222-3509-6

- McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Context. New York, Routledge, 1995.

- Paola Govoni, Un pubblico per la scienza. La divulgazione scientifica nell'Italia in formazione, Roma, Carocci, 2002, ch. 5 "Paolo Mantegazza. I rischi della divulgazione" - ISBN 88-430-2321-7

- Nicoletta Pireddu, Antropologi alla corte della bellezza. Decadenza ed economia simbolica nell'Europa fin de siècle, Fiorini, 2000, ch. 2 "Ethnos/Hedone/Ethos: Paolo Mantegazza, antropologo delle passioni - ISBN 88-87082-16-2

References[edit]

- ^ "1860-1900, Paolo Mantegazza and the dream of 'making' science popular". 1860-1900, Paolo Mantegazza and the dream of ‘making’ science popular. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ "The tension between globalisation and democracy". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2023-10-04.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mantegazza, Paolo". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 602.

Further reading[edit]

- Garbarino C; Mazzarello P. (2013). A strange horn between Paolo Mantegazza and Charles Darwin. Endeavour 37 (3): 184-187.

External links[edit]

- Works by Paolo Mantegazza at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Paolo Mantegazza at Internet Archive

- Works by Paolo Mantegazza at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- www.paolomantegazza.it The full text Quadri della natura umana. Feste ed ebbrezze

- Paolo Mantegazza on the power of coca. Cocaine.org.

- 1831 births

- 1910 deaths

- Italian anthropologists

- Italian medical writers

- Italian neuroscientists

- Italian physiologists

- People from Brianza

- People from Monza

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Authors of utopian literature

- 19th-century Italian novelists

- 20th-century Italian novelists

- Coca

- Italian male non-fiction writers

- Italian science writers

- Proponents of scientific racism

- Italian surgeons

- Physicians from Milan

- Academics from Milan

- 19th-century Italian politicians

- Italian liberal politicians