Jay Allen

Jay Allen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jay Cooke Allen 7 July 1900 |

| Died | 20 December 1972 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | journalist |

| Known for | war correspondent |

Jay Cooke Allen Jr. (Seattle, 7 July 1900 – Carmel, 20 December 1972) was an American journalist. He worked mostly for the Chicago Tribune, though his contributions appeared also in many other US newspapers, especially between the mid-1920s and the mid-1930s. He is known mostly as a foreign correspondent active during the Spanish Civil War; his interview with Francisco Franco, report from Badajoz and interview with José Antonio Primo de Rivera are at times considered 3 most important journalistic accounts of the conflict and made enormous impact around the globe. His work as war correspondent is extremely controversial: some consider him a model of impartial, investigative journalism, and some think his work an examplary case of ideologically motivated manipulation and fake news.

Early career (before 1936)[edit]

Infancy and youth[edit]

His father Jay Cooke Allen (1868–1948)[1] was born in Kentucky but he settled in Seattle and practiced as an attorney;[2] his mother Jeanne Maud Lynch (1876–1901)[3] was a first generation Irish-American. She died due to tuberculosis when Jay was 15-months old. The religion-motivated legal battle for custody over Jay ensued between Jeanne's Catholic relatives and the Methodist father, who eventually emerged victorious. Some authors speculate that the episode might have influenced later Allen's hostility towards the Catholic Church.[4] However, Allen's juvenile relations with his father were also tense, since Jay Allen Sr. became a violent alcohol addict.[5] Jay left home in his early teens and moved to the East Coast, where he became the boarder at the Pullman College in Washington. After graduation Jay Allen Jr. entered an unidentified faculty at the Harvard, where he received his master's degree in 1920.[6] Afterwards in the early 1920s he was employed by The Portland Oregonian.[7]

In Paris[edit]

In 1924 Allen married Ruth Myrtle Austin (1899–1990),[8] a woman from Woodburn in Oregon;[9] on they honeymoon the couple went to France. When in Paris they befriended Ernest Hemingway, who tipped Allen off that he was about to resign his job with the Paris office of the Chicago Daily Tribune. Allen immediately applied for the vacancy and was successful.[5] In 1925 he joined the paper's foreign service;[7] Allen's first signed correspondence in Tribune is dated February 19, 1926.[10] His only son Jay Cooke Michael (later an Episcopal priest and dean of the Berkeley Divinity School) was born in Paris in 1927.[5] Between 1924 and 1934 Allen remained formally based in France though he spent long spells abroad, especially in Geneva, where he reported from the League of Nations.[11] At the time he covered events in France, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Austria, Germany, Poland and the Balkans.[12] As foreign correspondent Allen travelled extensively across Europe and went as far as to the Polish-Lithuanian border.[13]

In Spain[edit]

Allen's job took him to Spain a few times in the late 1920s; he briefly resided in Madrid in 1930. The Allens became close friends to an aristocrat turned radical socialist Constancia de la Mora, who in turn introduced them to numerous left-wing activists.[5] He settled in Madrid again in early 1934, this time with the intention to go on as a journalist but also to study the agrarian question.[12] Allen resumed his personal contacts with radical left-wing journalists, intellectuals, artists and politicians. He forged friendship with Juan Negrín, Luis Araquistáin, Julio Álvarez del Vayo, Rodolfo Llopis, Luis Quintanilla and many others. Following the Asturian revolution he hosted in his apartment Amador Fernández, the leader of Asturian miners who went into hiding. In his correspondence to American press he remained highly sympathetic towards the revolutionaries; at one point he was arrested and interrogated by the police, but was soon set free.[5] In the mid-1930s Allen settled in Torremolinos, in a hotel owned by a British friend.[12]

Spanish civil war (1936–1937)[edit]

Interview with Franco[edit]

Following the news of the July Coup Allen immediately left Torremolinos and fled to Gibraltar; en route his car was mistakenly fired at – according to his own account – by "very nervous squad of Republican soldiers", who killed the driver.[14] In late July he shuttled between Gibraltar and the Spanish Morocco. As American press correspondent he gained access to the entourage of Francisco Franco and managed to secure[15] what is often erroneously[16] referred to as the first interview with the general after the coup.[17] The conversation took place on July 27 in Tetuán, and the interview appeared in News Chronicle of July 29, 1936. Allen presented Franco in rather unsympathetic though prophetic terms as an excessively self-confident "midget who would be a dictator",[18] the person consumed by anti-Masonic and anti-Marxist obsession. According to Allen when asked whether he was ready to "shoot half Spain", Franco confirmed that he was prepared to save the country from Marxism "at whatever cost".[19] This statement was also emphasized in the sub-title.[20]

Badajoz[edit]

Allen's whereabouts between late July and mid-August are not clear, though he probably shuttled between Gibraltar, Spanish Morocco and the international zone of Tanger. At some time – the exact date remains disputed – he flew from Tanger to Lisbon and than drove to the border town of Elvas. According to his own claim, on August 23 he visited Badajoz, the city taken by the Nationalist troops on August 14.[21] In late August he was back in Tanger.[22] On August 30, 1936 The Chicago Tribune published his correspondence, titled Slaughter of 4,000 at Badajoz, ‘City of Horrors’ and reportedly written in Elvas in the very early hours of August 25.[23][24] The article presented bestial atrocities of Nationalist troops, including machine-gunning of 1,800 Republican captives in the bull-ring. Other episodes, reportedly either witnessed by or referred to Allen, included executions of children, random killings on the streets and the organized action of burning the corpses.[25] The article immediately became a media scoop and was for weeks and months referred in various newspapers across the world.[26]

Interview with José Antonio Primo de Rivera[edit]

Following at least one more visit to Lisbon[27] some time in September 1936 Allen entered the Republican zone. Thanks to his friendship with Rodolfo Lópis, at the time sub-secretary in the newly formed Largo Caballero government, he managed to secure interview with José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the Falange leader imprisoned since March and held in the Alicante prison. The interview, in presence of anarchist militiamen, took place on October 3 in the prison premises; it was published in Chicago Daily Tribune on October 9, 1936.[28] According to the publication, José Antonio expressed dismay that traditional interests of the Spanish establishment were taking precedence over Falange's aims of sweeping social change, though some scholars speculate that the prisoner exaggerated to curry favors with his jailers.[29] Allen thought his performance "a magnificent bluff".[30] According to some, imprudent outbursts by José Antonio during the interview reinforced hostility of the anarchists and contributed to his later execution.[12]

American intermezzo (1937–1940)[edit]

Ken[edit]

Allen was last seen in Spain in May 1937, when in Bilbao[31] he interviewed a shot down German pilot, who earlier had taken part in the bombing raid over Guernica.[7] Some time in the spring he was fired by the Hearst-held anti-Republican Tribune.[32] At that time the Esquire publisher David Smart intended to launch a new magazine, a semimonthly called Ken; it was supposed to give the public the "lowdown" on world events as "insiders" see them, though the concept was increasingly evolving towards a magazine for the underdog, militantly antifascist. Allen was hired as the first editor-in-chief, largely thanks to his earlier Chicago Tribune correspondence. In early summer of 1937 Allen returned to New York and began to gather a staff of militant liberal writers. However, the owners were increasingly at a loss as to the format of Ken; also, Allen's idea "apparently savored too much of historical study" and was not very much appreciated. Eventually Allen was sacked and replaced with the onetime Tribune correspondent, George Seldes, who managed the short-lived magazine during the next few months to come.[33]

Aid to refugees and own literary plans[edit]

In 1938–1940 Allen resided in New York and was engaged in correspondence related to Spain, e.g. he propagated rumors that at the front the POUM militiamen played football with the Nationalists.[34] In 1938 he prefaced Robert Capa's photo album Death in the making.[35] Later he was engaged in assistance to refugees who reached the US. In May 1939 he was supposed to serve as an interpreter to Juan Negrín during his appointment with Roosevelt. The meeting was cancelled at short notice; eventually Negrin met Eleanor Rosevelt and Allen managed to forge a friendly relation with her. On behalf of the Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign he used to make frequent representations to the State Department.[36] He also toyed with an idea of writing a history of the Spanish Civil War; he worked with Herbert Southworth and Barbara Tuchman compiling data.[5] The project ended up as a 72-page manuscript on Badajoz; it has never been published. In the spring of 1940 Allen was deeply moved when Gustav Regler dedicated to him his book The Great Crusade.[5]

Back in Europe and Africa (1940–1943)[edit]

Emergency Rescue Committee[edit]

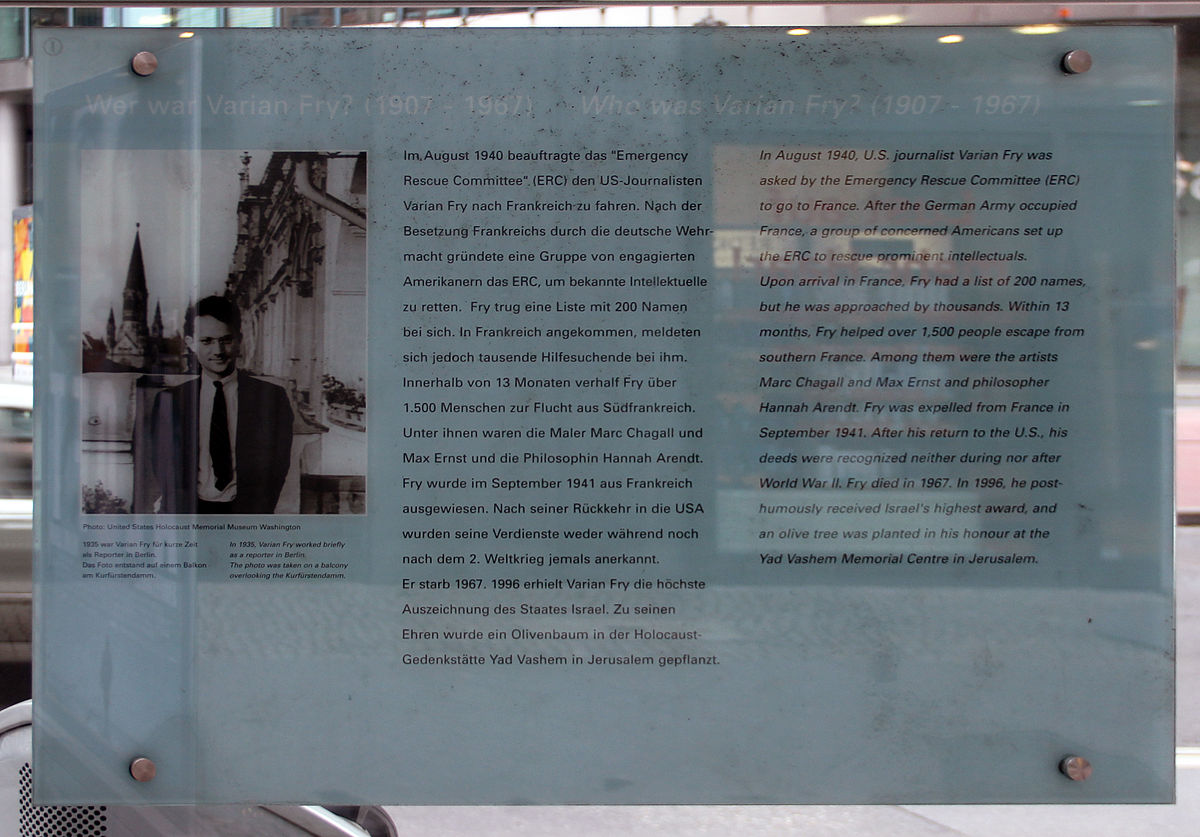

Some time in 1940 Allen became engaged with Emergency Rescue Committee, an American NGO set up to assist endangered individuals trapped in the Vichy France. Late that year he was appointed head of the existent ERC mission in Marseille. En route to France, in Africa, he interviewed general Weygand.[37] Upon arrival in Marseille Allen found himself in conflict with the hitherto head of the mission, Varian Fry; Allen denounced him to ERC as supporter of "POUM Trotskyites".[38] In January 1941 Allen interviewed Pétain and posed as a journalist impressed with Vichy France.[5] The struggle for control against Fry lasted until February 1941, when Allen departed to Paris. Independently of Fry he was mounting an operation of moving a group of people from Oran to Gibraltar.[39] However, he was followed by French security, which in March detained him when crossing the demarcation line back to the Vichy zone.[40] Also his Oran operation ended up in total failure, with most refugees arrested by the French security.[39]

Detainee[edit]

Upon arrest Allen was formally charged with illegal crossing of the demarcation line between the occupied and the Vichy parts of France. However, he was suspected of engagement in unspecified subversive activities, possibly involving spying or sabotage on part of the British. He was placed in prison in Chalon-sur-Saône and was held there until July 1941. He was Interrogated by the French police, SS and Gestapo, but according to his own account, he revealed no meaningful information on his ERC-related activities. In the summer he was moved to another prison in Dijon.[41] During his incarceration Allen lost 38 lb (some 17 kg). Though the US ambassador to Vichy admiral Leahy was rather skeptical and annoyed by suspected Allen's subversive activity, it was Eleanor Roosevelt who lobbied for US efforts towards Allen's release.[5] Eventually following 4 months behind bars he was exchanged for a German correspondent arrested in New York[42] and in August 1941 Allen was back in the United States.[7]

North African campaign[edit]

Back in the United States Allen became engaged with the US military, though neither the timing nor exact mechanism of his involvement are clear. The army propaganda department considered him knowledgeable and useful when preparing the plans for invasion in Africa. When Operation Torch commenced in November 1942, Allen was heading a propaganda unit named Psychological Warfare Branch. Following successful seizure of Algiers he was resident in the city within the compound formed by the general Eisenhower's headquarters; he appeared as an "assimilated" colonel.[5] There is little information on Allen's service, except that as head of "Office of War Information" he organized propaganda movies intended for French audience.[43] It is known that he served some 5 months, until March 1943, but none of the sources consulted provides information on reasons of his release. No Allen's press correspondence from the period of November 1942 – March 1943 has been identified. In the early spring of 1943 he was back in New York,[7] his successor in Algeria was Southworth.[44]

Retiree (after 1943)[edit]

Withdrawal into privacy[edit]

In 1944 Allen moved to Seattle to take care of his ailing father, but in 1947 the family settled in Carmel, California.[7] He intended to publish a book titled The Day Will End: a personal adventure behind Nazi lines; eventually this project came to nothing. He effectively retired as a press correspondent, living off his father's inheritance.[5] Exact reasons for his withdrawal into privacy are not clear. One scholar writes that "what happened exactly remains a mystery but it appears that there were few commissions coming his way, because he seems to have been blacklisted".[5] The suggestion advanced is that since FBI and Hoover personally considered Allen a Communist supporter[45] – the charge he denied[5] – he might have been subject to some harassment.[5] He was reportedly increasingly downcast and disillusioned, especially that "all conspired to drain away his optimism and determination to go fighting".[5] Another version of his withdrawal is that Allen was getting increasingly consumed by alcoholism.[46] One source claims he assumed an unspecified teaching role.[47]

Back-seat Hispanist[edit]

Allen followed scientific debate on recent history of Spain and at times attended related seminars, e.g. the one of 1964, organized in Stanford by the Hispanic America Society.[48] He remained in touch with many Hispanists, though particularly with Southworth, who turned from his junior research assistant[49] to a recognized though non-academic historian; he remained a great admirer of Allen.[50] Both considered themselves morally obliged to debunk lies of Francoist propaganda.[51] In the 1960s Allen warned Southworth about would-be CIA assassination;[52] he also tried to use his American literary connections to get Southworth's El mito de la cruzada de Franco released in the US, but to no avail.[53] He also cultivated friendship with Gerald Brenan, whom he inspired towards Spanish history back in the mid-1930s.[54] However, Allen was somewhat skeptical about Hugh Thomas, who reportedly refused to take sides and was "terribly fuzzy about a lot of things";[55] he remained also cautious about Burnett Bolloten.[56] Himself Allen published nothing. He died in 1972 because of a stroke.[7]

Controversies[edit]

Badajoz and Spanish Civil War reporting[edit]

Many scholars consider Allen one of the best informed foreign correspondents active during the Spanish Civil War, the one who avoided usual trappings and stereotypes and delivered competent, informative correspondence.[57] Some authors present Allen as a rare case of professional, impartial press journalist active during the Spanish war, as “dispassionate correspondents were nearly impossible to find”; the Badajoz article is listed as example of his craft.[58] The Badajoz article is indeed at times referred as a quintessence of reporting; one academic scholar of journalism noted that it "deserves to be read by every student of journalism".[59] His 3 pieces – interview with Franco, Badajoz report and interview with José Antonio – are at times referred as 3 most important journalistic contributions during the entire war. They made enormous impact, also globally, and until today they serve as key first-hand sources when discussing personality of Franco (shooting half Spain if necessary)[60] or Nationalist atrocities (bull-ring blood orgy and 4,000 killed in Badajoz).[61]

There is a group of historians who offer an entirely different perspective. According to this theory, already prior to 1936 Allen turned a zealous radical-left winger. In one version, after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War he immediately turned into a “soldado de papel”, a committed Republican propagandist ready for any manipulation, misrepresentation and outward lie needed when in service of the cause he supported;[62] in a slightly less damning version he was at least tilted towards the Republic.[63] Particular criticism is directed at the Badajoz correspondence; initially it was claimed that general figures and many episodes from this article were invented by Allen.[64] Recent works are supposed to demonstrate that Allen has visited neither Badajoz nor even the province of Badajoz and that he faked the entire correspondence, including false days when the article has allegedly been written and wired.[65] Some authors claim that Allen produced lies to divert attention from carnage in the Modelo prison.[66] Also authenticity of alleged Franco's comments is questioned.[67]

ERC Marseille mission[edit]

In some historiographic works related to ERC activities in Marseille and in France Allen is presented as a particularly repulsive figure.[68] He appears as dictatorial, bossy and arogant man, bullying and disdainful towards Americans who were supposed to be his subordinates; some scenes portray a hysterical person losing control and indulging in outbursts of fury.[39] Moreover, in various accounts he emerges as an entirely incompetent type who was neither willing to listen to more experienced colleagues nor to learn from his own mistakes, the one who boasted of his own importance. The operations he planned are depicted as amateurish and endangering rather than helping people; his own capture and the collapse of his Oran scheme are referred as “too perfect an end for a boasting, blustering fool not to give observers the moral satisfaction of seeing someone reap his just rewards”.[39] Some accounts suggest that Allen mounted unclear financial operations.[69] His personality is presented as opposite to this of Varian Fry, the genuine heart and mind of the Marseille ERC.

In an exactly antithetical perspective, advanced by one eminent historian, Fry and Allen appear in entirely different roles.[70] Fry is depicted as a “nervous and hypersensitive” person who resented reasonable arrangements offered by Allen. It was “too volatile” Fry, not Allen, who remained obsessed with his own status and desperately tried to cling to his position against clear orders from the ERC board back in New York.[5] Moreover, Fry is pictured as a narrow-minded manager, who when executing rescue missions focused merely on people of his own class, artists and intellectuals, while Allen had a broader view and was keen to help all anti-Fascists.[5] Allen's intention to run the Marseilles mission by proxy does not result from his incompetence, cowardice or laziness, but is a mark of his professional caution and far-sightedness. The ERC success of getting thousands of refugees to safety – including Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Heinrich Mann, Hannah Arendt and many others – is credited to Allen as his work.

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Jay Cooke Allen, Sr., [in:] Geni [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Maxine Block, Anna Herthe Rothe, Marjorie Dent Candee, Current Biography Yearbook vol. 2, New York 1961, p. 20

- ^ Jeanne Maud Allen, [in:] Geni [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War, London 2012, ISBN 9781780337425, page unavailable, see chapter Talking with Franco, Trouble with Hitler: Jay Allen

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Preston 2012

- ^ Vassar Miscellany News 01.03.1939 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ a b c d e f g New York Times 22.12.1972 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ some sources claim she died in 2002, Ruth Myrtle Allen, [in:] Geni [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Descendants of Thomas (Bybby) Bybee, [in:] Genealogy [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ The Chicago Tribune 19.02.1926 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ compare his correspondence in Chicago Sunday Tribune 07.02.1932 [acceessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ a b c d "Foreign correspondents in the Spanish Civil War" by Paul Preston. Instituto Cervantes Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine in Spanish

- ^ The Chicago Tribune 08.08.1928 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ information of the incident was soon published in the press, see e.g. the Paris issue of International Herald Tribune 20.05.1936 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ some authors speculate that the incident with Republican militias firing at Allen's car a week earlier helped him to get access to Franco, as Luis Bolin, who managed Franco's PR at the time, assumed that Allen was a friendly pro-Nationalist correspondent

- ^ Franco was interviewed for Reuters on July 20 and for the French L'Intransigeant on July 24, Jorge Vilches, 18 de Julio: mentiras y propaganda, [in:] El Espanol 18.07.2016 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Gannes, Harry & Repard, Theodore Spain in Revolt 1936 Left Book Club Edition, Victor Gollancz Ltd

- ^ Interview with Franco by Jay Allen in the 'News Chronicle, 29 July 1936, [in:] Bridgeman Images [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ this is exactly as printed in News Chronicle, see here. It is not clear what Franco said literally (assuming Allen's account is not faked), as it is not known in what language the conversation took place. Allen reportedly spoke good Spanish at the time, though the interview might have been taken also in French, spoken by Franco. There is no presence of an interpreter mentioned in the text

- ^ Antonio Cazorla-Sanchez, Franco: The Biography of the Myth, London 2013, ISBN 9781134449491, p. 74

- ^ Southworth, Herbert R. El mito de la cruzada de Franco. [The Myth of Franco's Crusade] Random House Mondadori. Barcelona. 2008. ISBN 978-84-8346-574-5

- ^ Moíses Domínguez Núñez, Jay Allen, el ‘Gran Houdini’ del periodismo de guerra, [in:] Historia en Libertad 14.07.2014 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Allen, Jay (1936-08-30). "Slaughter of 4,000 at Badajoz, 'City of Horrors', Is Told by Tribune Man". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ the heading read "The dispatch was written on Aug. 25 and sent to the cable office at Tangier, International Zone, Morocco". The very text began with "This is the most painful story it has ever been my lot to handle. I write it at 4 o’clock in the morning, sick at heart and in body, in the stinking patio of the Pension Central, in one of the tortuous white streets of this steep fortress town."

- ^ full text in Slaughter of 4,000 at Badajoz, ‘City of Horrors’, [in:] The Grand Archive [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ compare e.g. a Polish socialist daily Gazeta Robotnicza 22.07.1937 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy, Gerald Brenan: The Interior Castle: A Biography, London 2014, ISBN 9780571316816, p. lxviii

- ^ full text in La entrevista con Jay Allen en Alicante, [in:] Rumbos [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War: Reaction, Revolution, and Revenge, London 2007, ISBN 9780393345827, page unavailable

- ^ Stanley G. Payne, Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977, Madison 1999, ISBN 9780299165642, p. 225

- ^ for some time he resided earlier in Madrid, from where he was sending letters to congressmen and the US president about the "sinister farce" of the non-intervention policy, Julie Prieto, Partisanship in Balance: The New York Times Coverage of the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939, Stanford 2007, p. 28

- ^ "Jay Allen, por ejemplo, fue despedido del Chicago Daily Tribune por la simpatía que sus artículos suscitaban hacia la República", Paul Preston, Idealistas bajo las balas: Corresponsales extranjeros en la guerra de España, Madrid 2011, ISBN, page unavailable

- ^ Press:Insiders, [in:] Time 21.03.1938 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Amanda Vaill, Hotel Florida: Truth, Love, and Death in the Spanish Civil War, New York 2014, ISBN 9780374712037, p. 383

- ^ Ted Allan, This Time a Better Earth, by Ted Allan: A Critical Edition, Ottawa 2015, ISBN 9780776621654, p. XXIII

- ^ some details in Dominic Tierney, FDR and the Spanish Civil War: Neutrality and Commitment in the Struggle that Divided America, New York 2007, ISBN 9780822390626, pp. 94,95,99, 101

- ^ Andy Marino, American Pimpernel: The Man Who Saved the Artists on Hitler's Death-List, New York 2011, ISBN 9781448108121, page unavailable

- ^ Sheila Isenberg, A Hero of Our Own: The Story of Varian Fry, New York 2019, page unavailable

- ^ a b c d Marino 2011

- ^ The Press: Exchanged Prisoners, [in:] Time 11.08.1941

- ^ first-hand account of his incarceration was published as The Prisoners of Chalon, [in:] Harper's Magazine June 1942, [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Jay Allen, War Correspondent, Speaks at S.B.C. Friday Night, [in:] Nelson County Times 08.10.1942, [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Le Petit Marocain 07.01.1943 [accessed March 15, 12022]

- ^ Paul Preston, Herbert Southowrth, [in:] The Guardian 09.11.1999 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ Nick Redfern, Secret Societies: The Complete Guide to Histories, Rites, and Rituals, New York 2017, ISBN 9781578596461, page unavailable

- ^ opinion of Moíses Domínguez Núñez, Cómo se fabricó el mito de la matanza de Badajoz, [in:] YouTube service 04.02.2017, 24:30 to 25:15

- ^ Francisco J. Romero Salvadó, Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Civil War, London 2013, ISBN 9780810857841, p. 41. However, this information is not confirmed elsewhere, e.g. his obituary in New York Times does not mention any Allen's scholarly engagements

- ^ Darryl Anthony Burrowes, Historians at war. Cold war influence on Anglo-American representations of the Spanish Civil War [PhD thesis Flinders University], Adelaide 2016, pp. 219–220

- ^ Burrowes 2016, p. 197

- ^ in 1964 Southworth wrote to Allen: "I am not given to great expressions, but I hope that you could see … the affection and admiration I have always felt for you", quoted after Burrowes 2016, p. 187

- ^ in 1964 Allen told Southworth that his own continuing involvement in the Spanish Civil War was to ensure "that the historians do not pass on the big lies, debunked largely where Hitler and Mussolini were concerned but not Franco", quoted after Burrowes 2016, p. 194

- ^ "you were wise to keep out of Madrid. The Spanish might well begin to see you more clearly. And don’t forget that the woods are full of agents of the CIA and other cosy little groups… They get paid and my guess is they do their best to earn their money", quoted after Burrowes 2016, p. 190

- ^ Burrowes 2016, pp. 211, 219

- ^ Burrowes 2016, p. 87

- ^ Burrowes 2016, p. 215

- ^ Burrowes 2016, pp. 219–220

- ^ this is the profile which emerges in particular from a chapter dedicated to Allen in Preston 2012. The same or similar opinions e.g. in Arthur H. Landis, Spain, the Unfinished Revolution, New York 1972, ISBN 9780717804436, p. 51, Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: From the Crimea to Vietnam: the War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist, and Myth Maker, San Francisco 1989, ISBN 9780330308793, p. 201, José Antonio González Alcantud, Marroquíes en la guerra civil española: campos equívocos, Granada 2003, ISBN 9788476586655, p. 51, Gilbert H. Muller, Hemingway and the Spanish Civil War: The Distant Sound of Battle, New York 2019, ISBN 9783030281243, p. 1

- ^ Myra MacPherson, "All Governments Lie": The Life and Times of Rebel Journalist I. F. Stone, New York 2010, ISBN 9781416525394, p. 158

- ^ Tim Luckhurst, Compromising the first draft?, [in:] Richard Lance Keeble, John Mair (eds.), Afghanistan and the media: deadlines and frontiers, Suffolk 2010, ISBN 9781845494445, p. 95

- ^ for a handful of recent publications which with no reservations quote Allen’s interview see e.g. Russell Martin, Picasso's War, Tucson 2012, ISBN 9781936102259, p. 33, Andrés Rueda Román, Franco, el ascenso al poder de un dictador, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499674735, p. 186, Peter Anderson, Miguel Ángel del Arco Blanco, Mass Killings and Violence in Spain, 1936–1952: Grappling with the Past, London 2014, ISBN 9781135114855, p. 75, Xabier Irujo, Gernika, 1937: The Market Day Massacre, Reno 2015, ISBN 9780874179798, p. 18, Eduardo Galeano, Hunter of Stories, London 2018, ISBN 9781472128850, p. 74, Joan Maria Thomàs, José Antonio Primo de Rivera: The Reality and Myth of a Spanish Fascist Leader, London 2019, ISBN 9781789202090, p. 258

- ^ Helen Graham, The Spanish Republic at War 1936–1939, Cambridge 2002, ISBN 9780521459327, p. 112, Sebastian Balfour, Deadly Embrace: Morocco and the Road to the Spanish Civil War, Oxford 2002, ISBN 9780191554872, p. 295, Robert Garland Colodny, The Struggle for Madrid: The Central Epic of the Spanish Conflict, 1936–37, London 2009, ISBN 9781412839242, p. 152, Douglas Edward Laprade, Hemingway & Franco, Valencia 2011, ISBN 9788437083568, p. 37, Juan Miguel Baquero, El país de la desmemoria: Del genocidio franquista al silencio interminable, Madrid 2019, ISBN 9788417541927, p. 28, Herbert Southworth, Guernica! Guernica!: A Study of a Journalism, Diplomacy, Propaganda, and History, San Francisco 2021, ISBN 9780520336360, p. 133

- ^ Marta Rey García, Stars for Spain: la guerra civil española en los Estados Unidos, La Coruna 1997, ISBN 9788474928112, p. 205, Lucas Molina Franco, Pablo Sagarra, Óscar González, Grandes batallas de la Guerra Civil española 1936–1939: Los combates que marcaron el desarrollo del conflicto, Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788490606506, p. 34, Inocencio F. Arias, Esta España nuestra: Mentiras, la nueva Guerra Fría y el tahúr de Moncloa, Madrid 2021, ISBN 9788401027659, p. 82

- ^ Antohny Beevor, The Battle for Spain, London 2006, ISBN 9781101201206, page unavailable

- ^ Pío Moa Rodríguez, Los mitos de la guerra civil, Madrid 2004, ISBN 9788497341875, esp. the chapter Las matanzas de Badajoz y de la carcel Modelo Madrilena, also Pio Moa, Los mitos del franquismo, Madrid 2015, ISBN 9788490603741, Angel David Martín Rubio, Los mitos de la represión en la Guerra Civil, Madrid 2005, ISBN 9788496281202

- ^ Moíses Domínguez Núñez, Soldados de papel en la guerra civil española, Madrid 2021, ISBN 9788418816420, also Francisco Pilo Ortiz, Moises Domínguez Núñez, Fernando de la Iglesia Ruiz, La matanza de Badajoz. Ante los muros de la propaganda, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788492654284. The online and scaled down version in Moíses Domínguez Núñez, Jay Allen, el ‘Gran Houdini’ del periodismo de guerra, [in:] Historia en Libertad 14.07.2014 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ opinion of Ricardo de la Cierva, quoted after Pío Moa, El derrumbe de la segunda república y la guerra civil, Madrid 2001, ISBN 9788474906257, p. 538

- ^ opinions of Domínguez Núñez and Moa, Cómo se fabricó el mito de la matanza de Badajoz, [in:] YouTube service 04.02.2017. Some scholars suspect that the entire interview with Franco might have been faked and that Allen did not speak to the general at all, see comments about "supuesta entrevista", Jorge Vilches, 18 de Julio: mentiras y propaganda, [in:] El Espanol 18.07.2016 [accessed March 15, 2022]

- ^ three key works which offer this perspective are Andy Marino, American Pimpernel: The Man Who Saved the Artists on Hitler's Death-List, New York 2011, ISBN 9781448108121, Sheila Isenberg, A Hero of Our Own: The Story of Varian Fry, New York 2005, ISBN 9780595348824, and Rosemary Sullivan, Villa Air-Bel: World War II, Escape, and a House in Marseille, London 2007, ISBN 9780060732516

- ^ Isenberg 2005

- ^ this is the view offered by Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War, London 2012, ISBN 9781780337425, see especially the chapter Talking with Franco, Trouble with Hitler: Jay Allen

Further reading[edit]

- Darryl Anthony Burrowes, Historians at war. Cold war influence on Anglo-American representations of the Spanish Civil War [PhD thesis Flinders University], Adelaide 2016

- Moíses Domínguez Núñez, Soldados de papel en la guerra civil española, Madrid 2021, ISBN 9788418816420

- Sheila Isenberg, A Hero of Our Own: The Story of Varian Fry, New York 2005, ISBN 9780595348824

- Andy Marino, American Pimpernel: The Man Who Saved the Artists on Hitler's Death-List, New York 2011, ISBN 9781448108121

- Francisco Pilo Ortiz, Moises Domínguez Núñez, Fernando de la Iglesia Ruiz, La matanza de Badajoz. Ante los muros de la propaganda, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788492654284

- Paul Preston, We Saw Spain Die: Foreign Correspondents in the Spanish Civil War, London 2012, ISBN 9781780337425

External links[edit]

- "Un periodista bien informado" (in Spanish)